Only Students in Intensive Programs Attain Appreciable Competence; and Adherence to Public Language Education Policy Has Been Inconsistent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 28, 2003

July 28, 2003 BY HAND David O. Carson, Esquire General Counsel U.S. Copyright Office Library of Congress James Madison Memorial Building Room LM-403 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, D.C. 20559-6000 Re: Docket No. RM 2002-4 Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Dear Mr. Carson: Thank you for your letter of June 24, 2003 raising additional questions related to my May 14, 2003 testimony in the above-captioned proceeding. I have set forth my answers below, and then turn to the issues you noted were left open from my testimony. I should note at the outset, however, that because the Office’s questions were very detailed, my answers are very detailed. Thus, there is a risk of losing perspective. I caution the Office not to fall into that trap. As explained in my testimony and further explained below, the fact is that record companies have commercially distributed in the U.S. a miniscule number of CDs with technological protection measures (“TPMs”) – some 0.05% of the CDs shipped from calendar year 2001 to date (the period during which TPMs have been used on U.S. commercial releases). 1 That tiny number cannot be said to have had any material effect to date – and certainly not a substantial one – on the ability of users to make noninfringing uses of sound recordings. The proponents of the exemptions do not seriously suggest otherwise. Instead, their cases are based on an asserted fear of future harm because record companies have not forsworn the possibility of using protective technologies, which 1 Our calculations are based on manufacturers’ unit shipments for calendar years 2001 and 2002 and estimated half-year data for 2003. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Recordings by Artist

Recordings by Artist Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 10,000 Maniacs MTV Unplugged CD 1993 3Ds The Venus Trail CD 1993 Hellzapoppin CD 1992 808 State 808 Utd. State 90 CD 1989 Adamson, Barry Soul Murder CD 1997 Oedipus Schmoedipus CD 1996 Moss Side Story CD 1988 Afghan Whigs 1965 CD 1998 Honky's Ladder CD 1996 Black Love CD 1996 What Jail Is Like CD 1994 Gentlemen CD 1993 Congregation CD 1992 Air Talkie Walkie CD 2004 Amos, Tori From The Choirgirl Hotel CD 1998 Little Earthquakes CD 1991 Apoptygma Berzerk Harmonizer CD 2002 Welcome To Earth CD 2000 7 CD 1998 Armstrong, Louis Greatest Hits CD 1996 Ash Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 1 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1977 CD 1996 Assemblage 23 Failure CD 2001 Atari Teenage Riot 60 Second Wipe Out CD 1999 Burn, Berlin, Burn! CD 1997 Delete Yourself CD 1995 Ataris, The So Long, Astoria CD 2003 Atomsplit Atonsplit CD 2004 Autolux Future Perfect CD 2004 Avalanches, The Since I left You CD 2001 Babylon Zoo Spaceman CD 1996 Badu, Erykah Mama's Gun CD 2000 Baduizm CD 1997 Bailterspace Solar 3 CD 1998 Capsul CD 1997 Splat CD 1995 Vortura CD 1994 Robot World CD 1993 Bangles, The Greatest Hits CD 1990 Barenaked Ladies Disc One 1991-2001 CD 2001 Maroon CD 2000 Bauhaus The Sky's Gone Out CD 1988 Tuesday, January 23, 2007 Page 2 of 40 Recording Artist Recording Title Format Released 1979-1983: Volume One CD 1986 In The Flat Field CD 1980 Beastie Boys Ill Communication CD 1994 Check Your Head CD 1992 Paul's Boutique CD 1989 Licensed To Ill CD 1986 Beatles, The Sgt -

Matière-Lumière Matter-Light

TRANSFORMER matièRE-luMièRE matter-light transformer matter-light mat iè RE -lu M iè RE 2 3 4 5 MATIÈRE-LUMIÈRE MATTER-LIGHT Jean Michel Bruyère / lFKs Du ZhenJun Kurt hentschläger MiKKo hynninen sarah KenDerDine ulF langheinrich roBert lepage li hui thoMas Mcintosh eMManuel MaDan Julien Maire christian partos erwin reDl ryuichi saKaMoto JeFFrey shaw shiro taKatani saBuro teshigawara CoMMIssariat CuratoR richarD castelli LE 360 360 avenue Du Maréchal Juin LE Garage 169 BoulevarD rayMonD poincaré LE DôME granD-place BÉTHUNE 2011 CAPITALE RÉGIoNALE DE LA CULTURE 2 avril – 29 mai 2011 2nd April – 29th May 2011 6 7 MATIÈRE-LUMIÈRE MATTER-LIGHT PRÉFACE INTRoDUCTIoN 10 MATIÈRE-LUMIÈRE MATTER-LIGHT 12 ŒUVREs ARTWoRKs 16 JEAN Michel BRUyÈRE LE CHEMIN DE DAMASTÈS 18 DU ZHENJUN GLOBAL FIRE 28 KURT HENTschläGER ZEE 34 ULF Langheinrich LAG, LAND II 42 LI HUI AMBER, REINCARNATION 58 JULIEN MAIRE EXPLODING CAMERA, LOW RESOLUTION CINEMA 66 THoMAs MCINTosH, EMMANUEL Madan & MIKKo HyNNINEN ONDULATION 78 CHRIsTIAN PARTos AQUAGRAF, ELO, M.O.M., STEP-MOTOR ANIMATIONS 90 ERWIN REDL MATRIX II 104 Ryuichi SakamoTo + sHIRo Takatani LIFE - fluid, invisible, inaudible... 118 AVIE 128 JEFFREy Shaw 130 JEAN Michel BRUyÈRE LA DISPERSION DU FILS 132 ULF Langheinrich ALLUVIUM 140 REACToR 146 Sarah KENDERDINE & JEFFREy Shaw 148 RoBERT Lepage FRAGMENTATION 154 Saburo TEshigawara DOUBLE DISTRICT 162 CoMMIssARIAT CURAToR 170 CRÉDITs CREDITs 172 8 9 préface INTRoDUCTIoN D’avril à décembre, Béthune 2011, Capitale régionale de la culture, accueille plus de soixante manifestations artistiques, festives From April to December, Béthune 2011, Regional Capital of Culture, is hosting more than sixty festive and artistic functions, open et ouvertes à tous, réparties sur trois saisons thématiques. -

Rage in Eden Records, Po Box 17, 78-210 Bialogard 2, Poland [email protected]

RAGE IN EDEN RECORDS, PO BOX 17, 78-210 BIALOGARD 2, POLAND [email protected], WWW.RAGEINEDEN.ORG Artist Title Label HAUSCHKA ROOM TO EXPAND 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX BLUE NOTEBOOKS, THE 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX SONGS FROM BEFORE 130701/FAT CAT CD ASCENSION OF THE WAT NUMINOSUM 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY COVER UP 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS LTD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE BLOOD 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE DUB YA 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD PRONG POWER OF THE DAMAGER 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKED AND LOADED 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKTAIL MIXXX 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD BERNOCCHI, ERALDO/FE MANUAL 21ST RECORDS CD BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FA BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FAMILY 21ST RECORDS CD FLOWERS OF NOW INTUITIVE MUSIC LIVE IN COLOGNE 21ST RECORDS CD LOST SIGNAL EVISCERATE 23DB RECORDS CD SEVENDUST ALPHA 7 BROS RECORDS CD SEVENDUST CHAPTER VII: HOPE & SORROW 7 BROS RECORDS CD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM COLD A DIFFERENT DRUM MCD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM ON THE ROAD TO WISDOM A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE ALTERNATES AND REMIXES A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE EVENING BELL, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE FALLING STAR, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE MACHINE BOX A DIFFERENT DRUM BOX BLUE OCTOBER ONE DAY SILVER, ONE DAY GOLD A DIFFERENT DRUM CD BLUE OCTOBER UK INCOMING 10th A DIFFERENT DRUM 2CD CAPSIZE A PERFECT WRECK A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMIC ALLY TWIN SUN A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMICITY ESCAPE POD FOR TWO A DIFFERENT DRUM CD DIGNITY -

Sound and Video Anthology: Program Notes

Sound and Video Anthology: Program Notes Biophysical Music: Marco her gestural manipulation of digital thing that resonates with Terminal Donnarumma, Curator sound processing and matchless vocal Beach’s audiovisual orchestral work. skill. Their piece has no predetermined But what happens when the bioa- score, for this is composed in real Curator’s Note coustic sounds of multiple bodies time using the variations in the heart are networked into a large-scale rate of twelve musicians throughout It is with great delight that I intro- instrument? Heidi J. Boisvert and the performance. duce the reader to Computer Music colleagues feed the sound and data Their work allows us to intro- Journal’s 2015 Sound and Video An- from muscles and blood flow of five duce another area of investigation: thology. I have curated a series of dancers to genetic algorithms that, in the intermix of traditional and phys- diverse, yet interrelated, works on turn, produce organic, multilayered iologically informed performance the theme of biophysical music. With sonic and visual bodies. The result techniques. To explore this hybrid this term, I refer to live music pieces is a gracefully dark audio and video practice further, we look at the work based on a combination of physi- composition manifesting a creative by the influential BioMuse Trio, ological technology and markedly and physical tension between human where a violin player and a performer, physical, gestural performance. In and algorithmic agents. Shifting from the latter wearing the BioMuse bio- these works, the physical and physi- dance to body art, we see the con- electrical instrument, interact closely ological properties of the performers’ cept of the performer’s body as an with each other through sound and bodies are interlaced with the mate- instrument stretched to its limits. -

Below Is an Accompanying List for the Survey of Fiscally Sponsored Artists and Arts Projects in New York City

Below is an accompanying list for the Survey of Fiscally Sponsored Artists and Arts Projects in New York City. The goal of the survey is to collect demographic data as well as information about issues that matter to the workforce of fiscally sponsored artists and arts projects in New York City. Your input will be used to inform cultural planning underway by the City of New York. New York City Fiscally Sponsored Artists and Arts Projects: "Boyd Meets Girl" Debut Recording "David Ippolito: That Guitar Man from Central Park" "I Want a President": Collective Reading in D.C. "La Dottoressa, the Musical" "Marat/Sade" "Mechanics of Love" "The Outbounds: Imagine a World Without Rape "The Sun Shines East" "The Test" Documentary "Until You Are Loved" #CompassionConvos #NAME? #SOULSPARKLE with Rev. Lainie Love Dalby (Alex)andra Taylor Dance 137AC 13th Floor Storytellers 14x48 2 Persian Tales 2050 Legacy 27: a documentary 29th Street Playwrights Collective 2nd Mind Music 3 Voices Theatre 360 Repertory Company 3rd Kulture Kids 420: The Musical 5 x Lyd 5th Digit Dance 600 HIGHWAYMEN 8 Ball Community 9 AT 38 9 Horses 9 to 5 Productions A Canary Torsi A Collection of Shiny Objects A Different Measure A Fishing Line Sings A Gallery of Music A Mighty Nice Man A Mile In My Shoes, Inc A New York Carol, Everyone's Carol A Portrait of Marina Abramović A Stopping Place A space between A.Common ABE ABRAHAM MEMORIES ACI Discounted Tuition Program ACTE II ADARSH ALPHONS PROJECTS ADELMO GUIDARELLI OPERATION ADELMO * ADVICE PROJECT MEDIA AFGHANCULTUREMUSEUM FOUNDATION -

Motivational and Uplifting Songs for New Year's & Beyond

Motivational and Uplifting Songs for New Year's & Beyond Song Name Time Artist Album Theme A Change Will Do You Good 3:50 Sheryl Crow Sheryl Crow change A Quiet Revolution (Phatjack Remix) 7:40 Lustral Deeper Darker Secrets empowerment All the Above 5:11 Maino [feat. T-Pain] Blag Flag City living the dream All Things (Keep Getting Better) 3:14 Widelife (Queer Eye Theme) Life is good Andromeda 6:37 Chicane Behind the Sun reflection Anything's Possible 3:47 Johnny Lang Turn Around empowerment Applause 3:32 Lady Gaga Artpop celebration Auld Lang Syne 2:04 Red Hot Chilli Pipers Bagrock to the Masses celebration Auld Lang Syne (The New Years Anthem) 6:11 Mariah Carey Auld Lang Syne (The Remixes) new beginnings Beautiful Day 4:08 U2 All That You Can't Leave Behind empowerment, Life is good Believe 3:46 The Bravery The Sun and the Moon belief Better Days 3:36 Better Days Goo Goo Dolls Change; reflection Better Than Today 3:36 Kylie Minogue Better Than Today take a chance Brand New Book 3:47 Train Brand New Book new beginnings Bulletproof 3:28 La Roux The Gold EP personal growth Celebrate Love 4:54 Pick Me Off the Dirt Klangstrahler Projekt celebration Celebration 3:43 Celebrate! Kool & The Gang celebration Copyright © 2012 Indoor Cycling Association www.indoorcyclingassociation.com Celebration 3:35 Madonna Celebration - Single celebration Change 3:17 John Waite Ignition change Change 4:40 Taylor Swift Taylor Swift new beginnings Change 3:59 Tears For Fears Shout: The Very Best of Tears For Fears change Change is Good 4:11 Rick Danko Times Like -

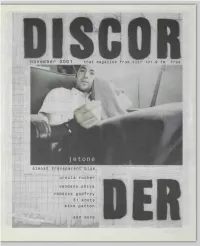

November 2001 That Magazine from Citr 101.9 Fm Free Almost Transparent

DISCOR november 2001 that magazine from citr 101.9 fm free almost transparent blue ursula rucker vandana shiva rebecca godfrey 31 knots mike patton and more DER 2 november 2001 SONSR 66 WATER STREETVANCOUVER CANADA Events at a glance: WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 7 G-NIOUS DJ BATTLE/EBONY & IVORY SOUND CREW @ GRANDE $6 all night long, students free before 11pm. SATURDAY NOVEMBER 10: HOUSE OF VENUS & BIGTIME Present DJ SPEN (BASEMENT BOYS) @ INSIDE flfflM.!»^ SUNDAY NOVEMBER 11: SPECIAL SUNDAY SESSIONS open til 2a Just because we're losers doesn't mean iented by Bo that we don't put in an effort! ^r^TJWfl SILENCE, WOOD, &UNK Marc Crawford: FRIDAY NOVEMBER 16: 31 Knots by Jane and James p.l Christa Min " nTHEBIGSHMOOZE Rebecca Godfrey by Doretta Lau p. 12 Brian Burke: Vandana Shiva by Thomas Hicks p. 13 Barbara Andersen ry Friday aft Mike Patton by Naben Ruthnum p. 13 Jetone by tobias p. 14 Reg Dunlop: xwer, drink specials. Almost Transparent Blue by Steve Dipo p. 16 Steve DiPasquale SUNDAY NOVEMBER 18: Ursula Rucker by Maren Hancock p. 18 Daniel and Henrik Sedin: Lori Kiessling and Matt Searcy 2GUERILLA, XLR8R & CITR Present MR. SCRUFF (Ninjatune/Manchester) Box Office: J-!ay. R —"- Ann Goncalves Markus Naslund: Doretta Lau TUESDAY NOVEMBER 20: The Enforcer: PHATT PHUNK Presents PETE TONG (Essential Mix, RADI01) Vancouver Special p. 4 Donavan Brashear n confirmed. Pete will finally I Strut, Fret, & Flicker p. 5 Would've designed much better Fucking Bullshit p. 5 third jerseys: 7" p. 6 Mike Payette, Scott Malin, Andrea Nunes, Black Ding Dong, Jay Panarticon p. -

Too Loud in ‘Ere

1 Too Loud In ‘Ere A Tale of 20 Years of Live Music Jonny Hall, June 2017 (c) Jonny Hall/DJ Terminates Here, 2017. Some rights reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. 2 Introduction Every live gig I’ve ever been to has given me some kind of story to tell. You could ask me about any of them and I could come up with at least one occurrence that captured the spirit of the night. But not every live show has been truly ‘special’. I’ve seen excellent performances by bands with crowds numbering in their thousands that were simply ‘very good nights out’. No more, no less. No, it’s those gigs that leave you buzzing all the way home that count, the ones where you really felt part of something special and years later, need only think of that occasion to be right back there, in soul if not in body. Sometimes the whole gig doesn’t have to be brilliant, a single ‘magic moment’ is all you need. And it’s those events that have kept me coming back for more. Most people just settle for a few favourites and watch them every time they come round. I’m not like that. I’ve rolled the dice on catching relatively unknown bands plenty of times (especially at festivals). You never know what you might discover. It doesn’t always work. I’ve had my share of dead nights, shitty soundsystems and line-ups that seem to shift every time you look at them. -

The Avastar of the Week Main Grid? ISABELLA Teen Residents Will Protest Over SAMPAIO Access to the Main Grid, but Is It P.31 a Good Idea? See P.4-5

ISSUE 17 | 04-13-2007 EVERY FRIDAY 150 L$ FREE COPY WWW.THE-AVASTAR.COM NEWS p.2-11 Linden Lab set to auction absent residents‘ land COMMENT p.5 Union between SL grids is neccessary - Pham Neutra BUSINESS p.13 RL firms take a new approach to Second Life A-STARS p.14-15 Designers under the hammer in charity auction STYLE p.16-19 Take a peek inside the homes of the famous in Star Cribs TRAVEL p.20-21 The Grendel‘s Children sim TEENS ON THE AVASTAR OF THE MAIN GRID? WEEK ISABELLA Teen residents will protest over SAMPAIO access to the main grid, but is it p.31 a good idea? See p.4-5 CATCHING SL‘S LOVE CHEATS - see p.8 VICTIMS TAUNTED BY CRUEL THIEF By CARRIE SODWIND • CRIMINAL HAS STOLEN THOUSANDS A THIEF is causing more misery for his victims by taunting them about • VICTIMS MOCKED OVER LOSSES his crimes. Full story - Page Three 0 NEWS Apr. 13, 2007 Apr. 13, 2007 NEWS 0 INSIDE E-MAIL OF OPINION THE WEEK CRUEL THIEF HITS SL “People from all over 500 LINDEN DOLLARS [email protected] the world, from dif- ferent cultures and WE want to hear YOUR opinion. comments to: yourmail@the-avas- legislations, come to- Is there an issue which angers or tar.com. The best emails will be gether in SL. It would moves you? Do you have a point printed in the newspaper, and you be necessary to verify you want to make? If so, then send will earn L$500 for each one that is in whose jurisdiction us an email with your views and published. -

London News, Global Views

LONDON NEWS, GLOBAL VIEWS KCWKENSINGTON, CHELSEA & WESTMINSTER, HAMMERSMITHto & FULHAM, WANDSWORTH a y AND SELECT LONDON BOROUGHS ISSUE 85 JULY 2019 FREE NEWS INTERNATIONAL NEWS OPINION & COMMENT BUSINESS & FINANCE EDUCATION HEALTH EVENTS ARTS & CULTURE DINING OUT MOTORING FASHION LITERATURE ASTRONOMY FISHING OUT OF TOWN TENNIS CROSSWORD BRIDGE CHESS : DULWICH PICTURE GALLERY CUTTING EDGE: MODERNIST BRITISH PRINTMAKING TO 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 Cyril Power, The Eight, © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, (2019) Bridgeman Images. Photo © Elijah Taylor (Brick City Projects) 2 July 2019 Kensington, Chelsea & Westminster Today www.KCWToday.co.uk Contents & Offices Kensington, Chelsea LONDON NEWS, GLOBAL VIEWS & Westminster Today KCWKENSINGTON, CHELSEA & WESTMINSTER, HAMMERSMITHto & FULHAM, WANDSWORTH a y AND SELECT LONDON BOROUGHS ISSUE 84 JUNE 2019 FREE Contents NEWS 80-100 Gwynne Road, London, OPINION & COMMENT BUSINESS & FINANCE HEALTH SW11 3UW DINING OUT EDUCATION (NURSERY & SPECIAL NEEDS) Tel: 020 7738 2348 MOTORING ARTS & CULTURE LIFESTYLE LITERATURE ASTRONOMY FISHING E-mail: [email protected] FLYING SPORT CROSSWORD Website: BRIDGE CHESS 3 News www.kcwtoday.co.uk PLUS WOODSTOCK 50 Advertisement enquiries: [email protected] 6 Architectural News Subscriptions: [email protected] COVER PICTURE: MILLO, DREAM, 2019, ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 100 X 70 CM. FROM THE SOLO EXHIBITION, Statue & Blue Plaque MILLO: WHERE THE STREETS DISAPPEAR, AT DOROTHY CIRCUS GALLERY, 35 CONNAUGHT STREET, Publishers: LONDON W2 2AZ. WWW.DOROTHYCIRCUSGALLERY.COM.