Experiment 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determination of the Molar Mass of an Unknown Solid by Freezing Point Depression

Determination of the Molar Mass of an Unknown Solid by Freezing Point Depression GOAL AND OVERVIEW In the first part of the lab, a series of solutions will be made in order to determine the freezing point depression constant, Kf, for cyclohexane. The freezing points of these solutions, which will contain known amounts of p-dichlorobenzene dissolved in cyclohexane, will be measured. In the second part of the lab, the freezing point of a cyclohexane solution will be prepared that contains a known mass of an unknown organic solid. The measured freezing point change will be used to calculate the molar mass of the unknown solid. Objectives and Science Skills • Understand and explain colligative properties of solutions, including freezing point depression. • Measure the freezing point of a pure solvent and of a solution in that solvent containing an unknown solute. • Calculate the molar mass of the unknown solute and determine its probable identity from a set of choices. • Quantify the expected freezing point change in a solution of known molality. • Quantitatively and qualitatively compare experimental results with theoretical values. • Identify and discuss factors or effects that may contribute to the uncertainties in values determined from experimental data. SUGGESTED REVIEW AND EXTERNAL READING • Reference information on thermodynamics; data analysis; relevant textbook information BACKGROUND If a liquid is at a higher temperature than its surroundings, the liquid's temperature will fall as it gives up heat to the surroundings. When the liquid's temperature reaches its freezing point, the liquid's temperature will not fall as it continues to give up heat to the surroundings. -

Δtb = M × Kb, Δtf = M × Kf

8.1HW Colligative Properties.doc Colligative Properties of Solvents Use the Equations given in your notes to solve the Colligative Property Questions. ΔTb = m × Kb, ΔTf = m × Kf Freezing Boiling K K Solvent Formula Point f b Point (°C) (°C/m) (°C/m) (°C) Water H2O 0.000 100.000 1.858 0.521 Acetic acid HC2H3O2 16.60 118.5 3.59 3.08 Benzene C6H6 5.455 80.2 5.065 2.61 Camphor C10H16O 179.5 ... 40 ... Carbon disulfide CS2 ... 46.3 ... 2.40 Cyclohexane C6H12 6.55 80.74 20.0 2.79 Ethanol C2H5OH ... 78.3 ... 1.07 1. Which solvent’s freezing point is depressed the most by the addition of a solute? This is determined by the Freezing Point Depression constant, Kf. The substance with the highest value for Kf will be affected the most. This would be Camphor with a constant of 40. 2. Which solvent’s freezing point is depressed the least by the addition of a solute? By the same logic as above, the substance with the lowest value for Kf will be affected the least. This is water. Certainly the case could be made that Carbon disulfide and Ethanol are affected the least as they do not have a constant. 3. Which solvent’s boiling point is elevated the least by the addition of a solute? Water 4. Which solvent’s boiling point is elevated the most by the addition of a solute? Acetic Acid 5. How does Kf relate to Kb? Kf > Kb (fill in the blank) The freezing point constant is always greater. -

Find the Molar Mass of Sodium Carbonate, Na 2CO3. Na 2 X

Moles and Molar Mass The mole is the "counting unit" used by chemists to indicate the number of atoms, ions, molecules, or formula units present in a particular chemical sample. The mole is similar to other counting units that you've used before....pair (2), dozen (12), and gross (144). One mole of a compound contains Avogadro's number (6.022 x 1023) of molecules (molecular compound) or formula units (ionic compound). The molar mass of a compound tells you the mass of 1 mole of that substance. In other words, it tells you the number of grams per mole of a compound. The units for molar mass are, therefore, grams/mole. To find the molar mass of a compound: 1. Use the chemical formula to determine the number of each type of atom present in the compound. 2. Multiply the atomic weight (from the periodic table) of each element by the number of atoms of that element present in the compound. 3. Add it all together and put units of grams/mole after the number. Example: Find the molar mass of sodium carbonate, Na2CO3. Na 2 x 23.0 = 46.0 C 1 x 12.0 = 12.0 O 3 x 16.0 = 48.0 molar = 106.0 g/mole mass For many (but not all) problems, you can simply round the atomic weights and the molar mass to the nearest 0.1 g/mole. HOWEVER, make sure that you use at least as many significant figures in your molar mass as the measurement with the fewest significant figures. -

2.1 Relative Atomic and Molecular Masses, the Avogadro Constant, and the Mole Calculations AQA Chemistry

2.1 Relative atomic and molecular AQA Chemistry masses, the Avogadro constant, and the mole Calculations The Avogadro constant Specification reference 3.1.2.2 MS 0.1 Recognise and use expressions in decimal and ordinary form MS 0.4 Use calculators to find and use power, exponential, and logarithmic functions MS 1.1Use an appropriate number of significant figures. Learning objectives After completing the worksheet you should be able to: carry out calculations using the Avogadro constant carry out calculations using numbers in standard and ordinary form substitute numerical values into algebraic equations, and change the subject of equations report calculations to an appropriate number of significant figures. Introduction One mole of any substance contains the same number of particles as the number of atoms in 12 g of carbon-12. This number of particles is a huge number and is called the Avogadro constant. It has a value of 6.02 1023 and is given the units of mol−1 (per mole). The relative atomic mass of an element in grams contains 6.02 1023 atoms or one mole of that element. The relative formula mass of a compound in grams contains 6.02 1023 particles (molecules or ions) or one mole of that compound. Therefore we use the term molar mass to describe the relative atomic or formula mass of a substance in grams and give it the unit g mol−1. To calculate the number of particles in a certain mass of a substance we can use the following equation. mass m (g) Number of particles = ´ 6.02 ´ 1023(mol-1) molar mass M (g mol-1) Worked example Question 1 How many molecules are there in 42.5 g of ammonia, NH3? Answer © Oxford University Press 2015 www.oxfordsecondary.co.uk/acknowledgements This resource sheet may have been changed from the original 1 2.1 Relative atomic and molecular AQA Chemistry masses, the Avogadro constant, and the mole Calculations Step 1 Calculate the molar mass of ammonia using the relative atomic masses of nitrogen and hydrogen from the periodic table. -

Answer Key Chapter 6: Standard Review Worksheet 1

Answer Key Chapter 6: Standard Review Worksheet 1. 1 amu = 1.66 _ 10–24 g. For example, the average atomic mass of sodium is 22.99 amu, which represents the average mass of all the sodium atoms in the world (including all the various isotopes and their relative abundances). So that we will be able to use the mass of a sample of sodium to count the number of atoms of sodium present in the sample, we consider that every sodium atom in a sample has exactly the same mass (the average atomic mass). The average atomic mass of an element is typically not a whole number of amu’s because of the presence of the different isotopes of the element, each with its own relative abundance. Since the relative abundance of an element can be any number, when the weighted average atomic mass of the element is calculated, the average is unlikely to be a whole number. 2. On a microscopic basis, one mole of a substance represents Avogadro’s number (6.022 _ 1023) of individual units (atoms or molecules) of the substance. On a macroscopic basis, one mole of a substance represents the amount of substance present when the molar mass of the substance in grams is taken (for example, 12.01 g of carbon will be one mole of carbon). 3. The molar mass of a compound is the mass in grams of one mole of the compound (6.022 _ 1023 molecules of the compound) and is calculated by summing the average atomic masses of all the atoms present in a molecule of the compound. -

Experiment 9

Experiment Molar Mass by Vapor Density 7 Vapor is the term for a gas produced from the vaporization of a liquid. If it is assumed that the resulting vapor is an ideal gas, then we can use the ideal gas law: By substituting moles for mass and molar mass the following equation is derived after some simple rearrangements: The molar mass of the compound is represented by Mm and d is the vapor density in g per liter. Another way to calculate the molar mass of the sample is to determine the moles of the gas produced. The number of moles can be determined from the measured volume, pressure, ad temperature of the gas. From the mass of the liquid sample used and the moles calculated from experimental measurements, the molar mass of the sample can be determined. Many organic compounds are liquids that vaporized below the boiling point of water. A boiling water bath will be used as a constant temperature (100 C or 373 K) heat source to convert your unknown liquid to a gas. The pressure of the gas will be the barometric pressure of the room and the volume is the volume of the gas inside the container (flask). In this experiment, you will be given an unknown liquid and you will determine the molar mass of the liquid. Equipment and Reagents Analytical balance unknown liquid high capacity balance 200 mL flask tap water thermometer Aluminum foil stand w/ iron ring barometer Pin wire gauze 600 mL beaker buret clamp 1 Procedure 1. On an analytical balance weigh a 200 mL Erlenmeyer flask with a piece of aluminum foil large enough to cover the mouth of the flask. -

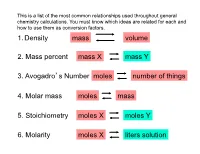

1. Density Mass Volume 3. Avogadro's Number Moles

This is a list of the most common relationships used throughout general chemistry calculations. You must know which ideas are related for each and how to use them as conversion factors. 1. Density mass volume 2. Mass percent mass X mass Y 3. Avogadro’s Number moles number of things 4. Molar mass moles mass 5. Stoichiometry moles X moles Y 6. Molarity moles X liters solution 1. Density mass volume • convert from mass to volume 6.54 g 1 cm3 = 8.32 cm3 = 8.32 mL 0.7857 g • convert from volume to mass 28.56 cm3 0.7857 g = 22.44 g 1 cm3 • calculate density directly density = 371 g = 19.2 g/mL 19.3 cm3 This is a list of the most common relationships used throughout general chemistry calculations. You must know which ideas are related for each and how to use them as conversion factors. 1. Density mass volume 2. Mass percent mass X mass Y 3. Avogadro’s Number moles number of things 4. Molar mass moles mass 5. Stoichiometry moles X moles Y 6. Molarity moles X liters solution 2. Mass percent mass X mass Y 55.5 g CuF2 37.42 g F = 20.8 g F 100 g CuF2 This is a list of the most common relationships used throughout general chemistry calculations. You must know which ideas are related for each and how to use them as conversion factors. 1. Density mass volume 2. Mass percent mass X mass Y 3. Avogadro’s Number moles number of things 4. Molar mass moles mass 5. -

Molar Mass 1 Molar Mass

Molar mass 1 Molar mass In chemistry, the molar mass is a physical property. It is defined as the mass of a given substance (chemical element or chemical compound) divided by its amount of substance. The base SI unit for molar mass is kg/mol. However, for historical reasons, molar masses are almost always expressed in g/mol. As an example, the molar mass of water is approximately: M(H O) ≈ 18 g⋅mol−1 2 Molar masses of elements The molar mass of atoms of an element is given by the atomic mass of the element multiplied by the molar mass constant, M −3 u = 1×10 kg/mol = 1 g/mol: M(H) = 1.007 97(7) × 1 g/mol = 1.007 97(7) g/mol M(S) = 32.065(5) × 1 g/mol = 32.065(5) g/mol M(Cl) = 35.453(2) × 1 g/mol = 35.453(2) g/mol M(Fe) = 55.845(2) × 1 g/mol = 55.845(2) g/mol. Multiplying by the molar mass constant ensures that the calculation is dimensionally correct: atomic weights are dimensionless quantities (i.e., pure numbers) whereas molar masses have units (in this case, grams/mole). Some elements are usually encountered as molecules, e.g. hydrogen (H 2), sulfur (S 8), chlorine (Cl 2). The molar mass of molecules of these elements is the molar mass of the atoms multiplied by the number of atoms in each molecule: M(H 2) = 2 × 1.007 97(7) × 1 g/mol = 2.015 88(14) g/mol M(S 8) = 8 × 32.065(5) × 1 g/mol = 256.52(4) g/mol M(Cl 2) = 2 × 35.453(2) × 1 g/mol = 70.906(4) g/mol. -

Molar Mass Calculation of Molar Masses Solutions Solutions

Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Molar Mass Calculation of Molar Masses Molar mass = Calculate the molar mass of the following Mass in grams of one mole of any element, Magnesium nitrate, Mg(NO 3)2 numerically equal to its atomic weight 1 Mg = 24.3050 Molar mass of molecules can be determined from the 2 N = 2x 14.0067 = 28.0134 chemical formula and molar masses of elements 6 O = 6 x 15.9994 = 95.9964 Molar mass of Mg(NO 3)2 = 148.3148 g Each H 2O molecule contains 2 H atoms and 1 O atom Calcium carbonate, CaCO 3 1 Ca = 40.078 Each mole of H O molecules contains 2 moles of H 2 1 C = 12.011 and 1 mole of O 3 O = 3 x 15.9994 One mole of O atoms corresponds to 15.9994 g Molar mass of CaCO 3 = 100.087 g Two moles of H atoms corresponds to 2 x 1.0079 g Sum = molar mass = 18.0152 g H 2O per mole Iron(II) sulfate, FeSO 4 Molar mass of FeSO 4 = 151.909 g Chapter 5 Chapter 5 Solutions Solutions Solution: a homogenous mixture in which the components are evenly distributed in each other The properties and behavior of solutions often depend not only on the type of solute but also on the concentration of the solute. Solute: the component of a solution that is dissolved in another substance Concentration : the amount of solute dissolved in a given quantity of solvent or solution Solvent: the medium in which a solute dissolved to form a solution – many different concentration units • (%, ppm, g/L, etc) Aqueous: any solution in which water is the solvent – often expressed as Molarity 1 Chapter 5 Chapter 5 Solution Concentrations Solution Concentrations Molarity = moles of solute per liter of solution Designated by a capital M (mol/L) Molarity can be used as a conversion factor. -

Chemical Engineering Vocabulary

Chemical Engineering Vocabulary Maximilian Lackner Download free books at MAXIMILIAN LACKNER CHEMICAL ENGINEERING VOCABULARY Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 2 Chemical Engineering Vocabulary 1st edition © 2016 Maximilian Lackner & bookboon.com ISBN 978-87-403-1427-4 Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 3 CHEMICAL ENGINEERING VOCABULARY a.u. (sci.) Acronym/Abbreviation referral: see arbitrary units A/P (econ.) Acronym/Abbreviation referral: see accounts payable A/R (econ.) Acronym/Abbreviation referral: see accounts receivable abrasive (eng.) Calcium carbonate can be used as abrasive, for example as “polishing agent” in toothpaste. absorbance (chem.) In contrast to absorption, the absorbance A is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species. A is calculated as ln (l0/l) with l0 being the initial and l the transmitted light intensity, respectively. absorption (chem.) The absorption of light is often called attenuation and must not be mixed up with adsorption, an effect at the surface of a solid or liquid. Absorption of liquids and gases means that they diffuse into a liquid or solid. abstract (sci.) An abstract is a summary of a scientific piece of work. AC (eng.) Acronym/Abbreviation referral: see alternating current academic (sci.) The Royal Society, which was founded in 1660, was the first academic society. acceleration (eng.) In SI units, acceleration is measured in meters/second Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 4 CHEMICAL ENGINEERING VOCABULARY accompanying element (chem.) After precipitation, the thallium had to be separated from the accompanying elements. TI (atomic number 81) is highly toxic and can be found in rat poisons and insecticides. accounting (econ.) Working in accounting requires paying attention to details. -

Density of Gases the Ideal Gas Law Applications SCIENTIFIC

Density of Gases The Ideal Gas Law Applications SCIENTIFIC Introduction Finding the density of a solid or a liquid is easily done. How does one find the density of a gas? Use this demonstration to find the density of three unknown gases and determine the identity of each gas. Concepts • Density • Molar mass Materials Gas samples (e.g., carbon dioxide, CO2; air; methane, CH4) Nail Balance, milligram Plastic bags, resealable, 1-qt size, 3 Clamps, Mohr pinchcock, 3 String Electrical tape Syringe, 60-mL, modified* Marker, permanent Syringe tip cap *See Preparation section. Tubing, latex, 10-cm length, 3 Safety Precautions Wear chemical splash goggles, chemical-resistant gloves, and a chemical-resistant apron. Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water before leaving the laboratory. Follow all laboratory safety guidelines. Please review current Material Safety Data Sheets for additional safety, handling, and disposal information. Preparation Modified Syringe 1. Pull the plunger out of the syringe barrel to the 60-mL mark. 2. Heat the tip of the nail, then press the hot tip through the plunger shaft near the end of the syringe barrel. 3. Remove the nail. 4. Optional: Attach the nail to the syringe barrel with string. Reheat the nail tip and press the tip through one “wing” of the syringe barrel. Tie a knot in one end of a piece of string, large enough so it won’t go through the hole. Thread the other end of the string through the hole from the bottom. Tie the free end of the string to the nail. Gas Delivery Apparatus 1. -

Mole & Molar Mass

Mole & Molar Mass Mole (mol): the amount of material counting 6.02214 × 1023 particles The value of the mole is equal to the number of atoms in exactly 12 grams of pure carbon-12. 12.00 g C-12 = 1 mol C-12 atoms = 6.022 × 1023 atoms The number of particles in 1 mole is called Avogadro’s Number (6.0221421 x 1023). 6.022 ×1023 atoms 1 mol or 1 mol 6.022 ×1023 atoms Converting between Number of Moles and Number of Atoms A silver ring contains 1.1 x 1022 silver Calculate the number of atoms in 2.45 atoms. How many moles of silver are in mol of copper. the ring? Atoms Ag mol Ag mol Cu Atoms 23 1 mol 6.022 ×10 atoms 1.1 ×1022 atoms Ag × 2.45 mol Cu × 6.022 ×1023 atoms 1 mol -2 24 = 1.8 × 10 mol Ag = 1.48 × 10 atoms Cu Molar Mass: the mass of 1 mol of atoms of an element An element’s molar mass in g/mol is numerically equal to the element’s atomic mass in amu. 1 mol C 12.01 g C or 12.01 g C 1 mol C Converting between Mass and Number of Moles Converting between Mass and Number of Atoms Calculate the moles of carbon in 0.0265 g of How many aluminum atoms are in a can pencil lead. weighing 16.2 g? g C mol C g Al mol Al atoms Al 1 mol C 0.0265 g C × 1 mol Al 6.022 ×1023 atoms 12.01 g C 16.2 g Al × × 26.98 g Al 1 mol -3 = 2.21 × 10 mol C = 3.62 × 1023 atoms Al Avogadro’s molar mass number Moles Formula units Gram (atoms, molecules, ions) Practice Problems 1.