Preserving Cultural Heritage Through Digitisation. Lebanon, As a Case Study’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf

The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral Report District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher '&# Aley Chouf Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher Georgia Dagher is a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. Her research focuses on parliamentary representation, namely electoral behavior and electoral reform. She has also previously contributed to LCPS’s work on international donors conferences and reform programs. She holds a degree in Politics and Quantitative Methods from the University of Edinburgh. The author would like to thank Sami Atallah, Daniel Garrote Sanchez, John McCabe, and Micheline Tobia for their contribution to this report. 2 LCPS Report Executive Summary The Lebanese parliament agreed to hold parliamentary elections in 2018—nine years after the previous ones. Voters in Aley and Chouf showed strong loyalty toward their sectarian parties and high preferences for candidates of their own sectarian group. -

Ufs Spring 2016 --- Program at a Glance

UfS Spring 2016 --- Program at a Glance FOR MEMBERS ONLY – NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED Lecture series Title Leader AUB’s 150th anniversary Maria Bashhur Abunnasr and Elie Kahale, Cynthia Myntti, Tony Naufal Under the spotlight Iqbal Doughan, Mariette Awad Heritage Tarek Mitri, George Asseily, Nadine Panayot Haroun Politics Hussein Kanaan, Nadeem Maasry Women series Azza Charara Beydoun, Rami Lakkis, Joumana Haddad Arts Hind Al Soufi, Omar AbdulAziz Hallaj, Nadia Kabbani, Hadi Maktabi Music Rima Khcheich, Elias Sahhab, Mehran Madani, Lama Tyan Health & wellbeing Antoine Courban, Faysal El Kak, Georges Karam Food and Nutrition Nuhad Daghir, Ghiwa Slaiby Study groups: Unlimited capacity Title Leader Saoud Al Mawla المنطقة العربية ما بين وعود الربيع ورعود الحروب اﻷهلية Fouad Fouad اﻷدب الصوفي: قراءة وتحليل لنماذج مختارة Philosophy in different keys Saleh Agha Brain Basics Arne Dietrich Self-Talk & Creating a Positive Reality Grace Ghannoum Khleif Cine club Abla Kadi FOR MEMBERS ONLY – REGISTRATION REQUIRED Study groups: Limited capacity Title Leader Healing the wounds of history – workshops Alexandra Asseily “I Remember, I Remember”: Memoir writing in the form Bert Hirschhorn and Mishka Mojabber Mourani of a prose poem Sketching studio for beginners Mona Jabbour Laughter Yoga May Haddad Introduction to digital photography Jirji Bachir The use of Photoshop Dana Zaidan and Norma Bakhti Create your professional website easily Mohammad El Medawar Web browsing Mohammad El Medawar Smartphones: iPhone Amani Zaidan iPad George El Khoury Social media -

Our Holy Father RAPHAEL Was Born in Syria in 1860 to Pious Orthodox Parents, Michael Hawaweeny and His Second Wife Mariam

In March of 1907 Saint TIKHON returned to Russia and was replaced by From his youth, Saint RAPHAEL's greatest joy was to serve the Church. When Archbishop PLATON. Once again Saint RAPHAEL was considered for episcopal he came to America, he found his people scattered abroad, and he called them to office in Syria, being nominated to succeed Patriarch GREGORY as Metropolitan of unity. Tripoli in 1908. The Holy Synod of Antioch removed Bishop RAPHAEL's name from He never neglected his flock, traveling throughout America, Canada, and the list of candidates, citing various canons which forbid a bishop being transferred Mexico in search of them so that he might care for them. He kept them from from one city to another. straying into strange pastures and spiritual harm. During 20 years of faithful On the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1911, Bishop RAPHAEL was honored for his 15 ministry, he nurtured them and helped them to grow. years of pastoral ministry in America. Archbishop PLATON presented him with a At the time of his death, the Syro-Arab Mission had 30 parishes with more silver-covered icon of Christ and praised him for his work. In his humility, Bishop than 25,000 faithful. The Self-Ruled Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of RAPHAEL could not understand why he should be honored merely for doing his duty North America now has more than 240 U.S. and Canadian parishes. (Luke 17:10). He considered himself an "unworthy servant," yet he did perfectly Saint RAPHAEL also was a scholar and the author of several books. -

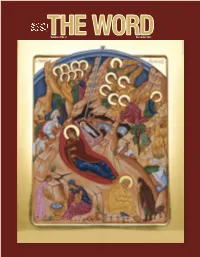

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO. 9 DECEMBER 2017 COVER: ICON OF THE NATIVITY EDITORIAL Handwritten icon by Khourieh Randa Al Khoury Azar Using old traditional technique contents [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL CELEBRATING CHRISTMAS by Bishop JOHN 5 PLEADING FOR THE LIVES OF THE DEFINES US PEOPLE OF THE MIDDLE EAST: THE U.S. VISIT OF HIS BEATITUDE PATRIARCH JOHN X OF ANTIOCH EVERYONE SEEMS TO BE TALKING ABOUT IDENTITY THESE DAYS. IT’S NOT JUST AND ALL THE EAST by Sub-deacon Peter Samore ADOLESCENTS WHO ARE ASKING THE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION, “WHO AM I?” RATHER, and Sonia Chala Tower THE QUESTION OF WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN IS RAISED IMPLICITLY BY MANY. WHILE 8 PASTORAL LETTER OF HIS EMINENCE METROPOLITAN JOSEPH PHILOSOPHERS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE ADDRESSED THIS QUESTION OF HUMAN 9 I WOULD FLY AWAY AND BE AT REST: IDENTITY OVER THE YEARS, GOD ANSWERED IT WHEN THE WORD BECAME FLESH AND THE LAST PUBLIC APPEARANCE AND FUNERAL OF DWELT AMONG US. HE TOOK ON OUR FLESH SO THAT WE MAY PARTICIPATE IN HIS HIS GRACE BISHOP ANTOUN DIVINITY. CHRIST REVEALED TO US WHO GOD IS AND WHO WE ARE TO BE. WE ARE CALLED by Sub-deacon Peter Samore 10 THE GHOST OF PAST CHRISTIANS BECAUSE HE HAS MADE US AS LITTLE CHRISTS BY ACCEPTING US IN BAPTISM CHRISTMAS PRESENTS AND SHARING HIMSELF IN US. JUST AS CHRIST REVEALS THE FATHER, SO WE ARE TO by Fr. Joseph Huneycutt 13 RUMINATION: ARE WE CREATING REVEAL HIM. JUST AS CHRIST IS THE INCARNATION OF GOD, JOINED TO GOD WE SHOW HIM OLD TESTAMENT CHRISTIANS? TO THE WORLD. -

AL-KULLIYYAH ISSUED by the American University

From left 10 right:- Dr. Hall. Dr. John Carruthers, Pres. Dodge L.L.D., and Dr. Ward. AL-KULLIYYAH ISSUED BY THE American University. of Beirut FORMEI:tLY THE SYRIAN PROTESTANT COLLEGE VOL. XIII. NOVEMBER, 1926 NO.1 THE LIFE OF CLEVELAND H. DODGE The Great Friend oj the Near East. I have been requested by the editor of the English issue of AI-Kulliyyah to prepare an article on Cleveland H. Dodge, placing special emphasis on his interest in the Near East. All I can do is to state a few facts simply-their unusual significance must be left to the imagination of the reader. Cleveland H. Dodge came from an old American family which has been distinguished for many generations for its re ligious zeal and philanthropy. The first member settled in Salem, Mass., in 1629. The first New York member of the family was David Low Dodge, born in Connecticut in 1774. He came to New York in 1805 as a partner in the largest wholesale dry goods house in the city. David married a daughter of the Rev. Aaron Cleveland, grandfather of Grover Cleveland-a former president of the United States. David Low Dodge founded a line of philanthropists. For five generations the name has been prominent in finance, social and religious work. He was one of the founders of the American Tract and Bible Society and the first president of the American Peace Society. He wrote several books on religious subjects, one being "War Inconsistent with the Religion of Jesus Christ." His son, William Earl Dodge, became in 1833 a partner in Phelps, Dodge and Co., which is still one of the greatest houses in the metal industries. -

Postcolonial Syria and Lebanon

Post-colonial Syria and Lebanon POST-COLONIAL SYRIA AND LEBANON THE DECLINE OF ARAB NATIONALISM AND THE TRIUMPH OF THE STATE Youssef Chaitani Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Youssef Chaitani, 2007 The right of Youssef Chaitani to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. ISBN: 978 1 84511 294 3 Library of Middle East History 11 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Minion by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword ix Introduction 1 1The Syrian Arab Nationalists: Independence First 14 A. The Forging of a New Alliance 14 B. -

118102 JAN. 2009 WORD.Indd

Volume 53 No. 1 January 2009 VOLUME 53 NO. 1 JANUARY 2009 contents COVER THEOPHANY: The Baptism of Christ 3 EDITORIAL by Rt. Rev. John Abdalah 4 CANON 28 OF THE 4TH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL by Metropolitan PHILIP 10 METROPOLITAN PHILIP HOSTS ANTIOCHIAN SEMINARIANS IN ANNUAL EVENT 14 FR. FRED PFEIL INTERVIEWS FR. DAVID ALEXANDER, The Most Reverend US NAVY CHAPLAIN Metropolitan PHILIP, D.H.L., D.D. Primate 17 DEPARTMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRIES The Right Reverend Bishop ANTOUN 21 ORATORICAL FESTIVAL The Right Reverend Bishop JOSEPH The Right Reverend 23 COMMUNITIES IN ACTION Bishop BASIL The Right Reverend 31 ORTHODOX WORLD Bishop THOMAS The Right Reverend 35 THE PEOPLE SPEAK … Bishop MARK The Right Reverend Bishop ALEXANDER Icons courtesy of Come and See Icons. Founded in Arabic as www.comeandseeicons.com Al Kalimat in 1905 by Saint Raphael (Hawaweeny) Founded in English as The WORD in 1957 by Metropolitan ANTONY (Bashir) Editor in Chief The Rt. Rev. John P. Abdalah, D.Min. Assistant Editor Christopher Humphrey, Ph.D. Editorial Board The Very Rev. Joseph J. Allen, Th.D. Anthony Bashir, Ph.D. The Very Rev. Antony Gabriel, Th.M. The Very Rev. Peter Gillquist Letters to the editor are welcome and should include the author’s full name and Ronald Nicola parish. Submissions for “Communities in Action” must be approved by the local Najib E. Saliba, Ph.D. pastor. Both may be edited for purposes of clarity and space. All submissions, in The Very Rev. Paul Schneirla, M.Div. hard copy, on disk or e-mailed, should be double-spaced for editing purposes. -

The Holy Hieromartyr Joseph of Damascus and His Companions

the akolouthia for the commemoration of The Holy Hieromartyr Joseph of Damascus and his Companions (+ 10 July 1860) The work of the Nun Mariam (Zaka) Abbess of the Holy Monastery of St John the Baptist Douma El-Batroun Lebanon Original Arabic Text 1993 – English Translation 2008 TYPIKON If the commemoration FALLS ON a Sunday AT GREAT VESPERS on Saturday evening, after the Proëmiakon (Ps. 103) Bless the Lord, O my soul and the 1st Kathisma of the Psalter (Pss. 1-8) Blessed is the man, we chant Lord, I have cried in the tone of the week with six stichera for the Resurrection in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos and four stichera for the Saints, Glory for the Saints, and Both Now and the first Theotokíon in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos. After the Entrance with the censer we chant O gladsome Light followed by the Prokeimenon of the day The Lord is King and the three lessons for the Saints. At the Aposticha we chant all of the stichera for the Resurrection in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos, Glory for the Saints, and Both Now and the Theotokíon in tone 8 from the Octoëchos. At the Apolytikia we chant that of the Resurrection in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos, Glory and that of the Saints, and Both Now and the Resurrectional Theotokíon in tone 5 from the Octoëchos. The Great Dismissal as usual. AT THE MIDNIGHT OFFICE on Sunday morning, we chant the Triadikos Canon in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos, the Litiya Troparia for the Saints, followed by It is truly meet to laud the transcendent Trinity and the other Megalynaria. -

July/August 2012

a St. Gregory’s Journal a July/August, 2012 - Volume XVII, Issue 7 St. Gregory the Great Orthodox Church - A Western Rite Congregation of the Antiochian Archdiocese o human being can worthily praise the holy passing of the Mother of God - not if he had ten thousand tongues Nand as many mouths! Even if all the tongues of the world’s scattered inhabitants came together, they could not From a approach a praise that was fitting. It simply lies beyond the realm of oratory. But since God loves what we offer, out of homily of longing and eagerness and good intentions, as best we know Saint John of how, and since what pleases her Son is also dear and delightful to God’s mother, come, let us again grope for words of praise... Damascus et the heavens rejoice now, and the angels applaud; let the died AD 760AD Learth be glad now [Ps. 96:911; 97:1], and all men and feast day - March 27 women leap for joy! Let the air ring out now with happy song, and let the black night lay aside its gloomy, unbecoming cloak of darkness, to imitate the bright radiance of day in sparkles of flame. For the living city of the Lord God of hosts is lifted up, and kings bring a priceless gift from the temple of the Lord, the wonder of Sion to the Jerusalem on high who is free and is their mother [Gal. 4:26]; those who were appointed by Christ as rulers of all the earth - the Apostles - escort to heaven the ever-virgin Mother of God! Inside: he Apostles were scattered everywhere on this earth, fishing for men and women with the varied and sonorous St. -

Samir Müller Painter of Clay

Samir Müller Painter of Clay 1 June – 24 September 2018 The Sursock Museum presents Samir Müller: Painter of Clay as part of a cycle of homages to artists featured in the collections of the Sursock Museum. This series of exhibitions is supported by Banque Libano-Française. Since its founding in 1930, Banque Libano-Française has always demon- strated its support for the arts, culture, and the preservation of cultural heritage in Lebanon and beyond. Banque Libano-Française is proud to support this series of exhibitions at the Sursock Museum, paying tribute to important artists in the history of Lebanese art. Samir Müller: Painter of Clay brings together ceramic panels, forms, and drawings by the artist. With the support of Banque Libano-Française Preferred wine partner Château Marsyas Lender of artworks May Müller Lighting Joe Nacouzi Exhibition graphics Mind the gap Author Yasmine Chemali Translation Sarah Morris Photographic reproduction of artworks Elie Abi Hanna Booklet design Mind the gap Printing Byblos printing Special thanks May Müller for the loan of ceramics to the Sursock Museum and for access to, and use of, archival material relating to Samir Müller; David Hury for his photographs and his eagerness to share information; Paul Abi Khattar Zgheib and Odile Khoury at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK). Cover Enameled samples on which Samir Müller worked to obtain the desired color. The colors’ formulas are written on the back (see back cover). Samir Müller (1959-2013) was a painter who used clay for canvas, engobe for pigment, and his fingers for brushes. His ceramic paintings include abstract landscapes, dancing figures on globular vases, and urban scenes in which human silhouettes haunt the streets of Beirut. -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Thursday, October 15, 2020 Report #211 Time Published: 10:30 PM New in the report: - Memorandum No. 107 / A.M. / 2020 dated 10/14/2020 on the mechanism for controlling the conditions of those in custody and the procedures to be implemented at the level of governorates, districts, municipalities and the Lebanese Red Cross. Number of Cases by Location • 9,865 case is Under investigation Beirut 134 Chouf 249 Zahleh 106 Matn 213 Ein Al Mreisseh 2 Chiah 21 Mar Michael 1 Borj Hammoud 15 AUB 1 Jnah 4 Rasieh 5 Nabaa 2 Ras Beirut 3 Ouzai 9 Barbara 2 Sin El Fil 18 Qoreitem 1 Bir Hassan 3 Maallaqa 4 Jdeidet Al Metn 7 Raouche 6 Ghobeiry 8 Karak Nouh 3 Bouchrieh 7 Hamra 16 Ein Al Remmaneh 14 Oumara Al Arady 1 Dora 4 Ein Al Teeneh 1 Forn Al Shubbak 6 Hoch Al Oumara 5 Rawda 6 Mseitbeh 3 Haret Hreik 33 Arady 6 Sed Bouchrieh 6 Mar Elias 5 Lailaki 13 Forzol 1 Sabtieh 7 Tallet Al Khayyat 3 Borj Al Barajneh 44 Qaa Al Rim 3 Mar Roukoz 1 Dar Al Fatwa 2 Mreijeh 10 Ksara 5 Dekwene 19 Tallet Al Drouz 1 Tahweetet Ghadir 7 Chtoura 1 Antelias 19 Zarif 3 Baabda 7 Jlala 1 Manqlt Mezher 2 Mazraa 13 Brazilia 2 Makseh 1 Jal El Dib 10 Borj Abi Haidar 4 Hazmieh 9 Taalabaya 7 Naqqash 7 Basta Fawka 6 Fayadieh 2 Jdita 5 Zalka 5 Tariq Jdeedeh 18 Mar Takla 1 Saadnayel 9 Byaqout 4 Ras Al Nabaa 10 Yarze 1 Qab Elias 10 Dbayyeh 4 Basta Tahta 1 Hadat 24 Bouarej 4 Deir Aoukar 2 Mar Michael Nahr 1 Loueizy 1 Bar Elias 5 Mansourieh 7 Ashrafieh 25 Kfarshima 9 Majdel Anjar 7 Fanar 4 Others 9 Wady Shahrour 2 Riyak 1 Ein Saadeh 5 -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Sunday, October 11, 2020 Report #207 Time Published: 10:30 PM New in the report: - Ministry of Interior and Municipalities Decision No. 1250 of 10/11/2020 related to the closure of some villages and towns due to the high number of Coronavirus cases in their residents. Number of Cases by Location • 9,635 case is Under investigation Beirut 80 Saida 75 Chouf 91 Matn 133 Ashrafieh 6 Ashrafieh 1 Barouk 12 Bouchrieh 5 Basta Fawka 2 Bqosta 2 Jiyyeh 5 Khenshara 1 Gemmayze 1 Haret Saida 2 Khreibeh 4 Dekwene 14 Hamra 7 Hababieh 1 Damour 1 Dora 3 Rmeil 1 Darb El Seem 2 Semqaniyyeh 3 Rabieh 1 Raouche 4 Old Saida 10 Mgheira 1 Rabweh 5 Sanayeh 2 Dakraman 1 Mghayrieh 1 Rawda 2 Tariq Jdeedeh 8 Tanbourite 1 Naameh 3 Zalka 4 Mazraa 3 Aabra 4 Btalloun 8 Sabtieh 1 Mseitbeh 7 Aqtaneet 1 Barja 2 Atshana 1 Manara 4 Anqoun 2 Borjen 1 Fanar 5 Borj Abi Haidar 3 Ein El Helwe 9 Baadaran 1 Qalaa 1 Tallet Al Khayyat 5 Ein El Delb 1 Baaqleen 10 Mteileb 1 Ras Nabaa 2 Ghazieh 2 Baqaata 4 Monteverde 2 Ras Beirut 2 Qayyaaa 2 Jadra 2 Mansouriyye 6 Ein Al Mreisseh 1 Kefraya 1 Darayya 1 Naqqash 3 Mar Elias 2 Majdelyoun 5 Sibline 1 Elissar 1 Others 20 Maghdoushe 1 Chhim 3 Antelias 6 Baabda 132 Miyyeh w Miyyeh 5 Ethreen 1 Bteghreen 1 Ouzai 2 Hlalieh 1 Ein Zhalta 5 Borj Hammoud 10 Loueizy 1 Others 21 Freidees 1 Broummana 3 Arayya 1 Akkar 18 Kfarfaqoud 1 Bsalim 3 Jnah 3 Bebnin 2 Kfarnabrakh 6 Baabdat 2 Hazmieh 8 Beit Mlat 1 Niha 1 Bekfayya 1 Hadat 16 Jdeidet Aydamoun 1 Others 13 Byaqout 2 Chiah 9 Halba 3 Aley 51 Beit Al