Don't Stop The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raitio 2 / 1996

ITIO 1996 VARIOTRAM HELSINGIN VALINTA LONTOON BUSSIII IKENNE I 992-94 Teksli Kimmo Nyhnder Kwa Krister Engberg Lontoon bussiliikenteessä on tapahtunut palion muuloksia Raitiossa 2'1993 olleen iutun iälkeen. (Lontoosta myös numeroissa 3.1990 ia 1.1991). Tässä muutamia päätapahtumia vuosina 1992-94. Vuoden 1995 tapahtumis- ta kerromme Påätepysäkki-palstalla myöhemmin' Aluksi kertauksen vuoksi Lon- Uudet käksikenosbussit olivat ensimmäinen nivelbussi Loriloon toon liikennelaitoksen bussipue tyyppiå Leyland Olympian / Alex- liikenteessä. len - London Buses Ltd. (LBL) - arder (LBL:n tyyppimerkintä L), yksiköti London Central, Selkent, Scania N113DRB / Notthem vuosl tgs:l south London, London General, Counlies (S), DAF D8220 / Oprare London United, Centrewe$, Met- Spectra (SP) ia Votuo B10M / Edellis€nä wonna aloiteltuja roline, London Northem, Leåside Nodhetn Counties (VC). Routemasler- ja Greenway -pro- Buses, East London, Westlink F jekt€ia iatkeniin edelleen. Linian London Coaches. Tåhän joukl(oon Uuder yksikenosbussit olivat '1 8 Countdown-kokeilu oli menes- oli kuulunut myös London Forest, tyyppiä DAF S8220, koreina lka- tys ia sen laaiedamistakin suunni mulla se joutui lopettamaan toi- rus Citibus (DK) ia Oprate Delta leltiin. Capital Citybusin Buscorn- mintansa häviltyåän kilpailutuk- (DA) s€kå Dennis Lance Alexan- kokeilusta ei kuulunut uulisia, sen sessa usermmat linjansa vuoden der -kodlh (LA). Lisäksi tuli valta- siiaan Hanowin alueelle suunoi- 1 991 -1opulla. Yksiköts{ä suutin oli va mäårå midibusseja Pååasiassa t€ltiin suuna kortlikokeilua. Se Lordon General 594 bussi[a, pi+ D€nnb Dan -alusialla vanatettu- kesläisi 18 kuul€una ia siinä olisi nin Metroline 344 bussilla. LBL:n na Phnon ia Wdghl Handybus- mukana 200 busgia. Låitetoimitta- lisaksi liikennettå hoiti kilpailutuk- koreilla (DR, DRL ja DW). -

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Report 03/2014 February 2014 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Contents Summary 5 Introduction 6 Preface 6 Key definitions 6 The incident 7 Summary of the incident 7 Context 7 Events preceding the incident 9 Events following the incident 11 Consequences of the incident 11 The investigation 12 Sources of evidence 12 Key facts and analysis -

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

An Auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground

£5 when sold in paper format Available free by email upon application to: [email protected] An auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground Collectables Enamel signs & plates, maps, posters, badges, destination blinds, timetables, tickets & other relics th Saturday 25 February 2017 at 11.00 am (viewing from 9am) to be held at THE CROYDON PARK HOTEL (Windsor Suite) 7 Altyre Road, Croydon CR9 5AA (close to East Croydon rail and tram station) Live bidding online at www.the-saleroom.com (additional fee applies) TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Transport Auctions of London Ltd is hereinafter referred to as the Auctioneer and includes any person acting upon the Auctioneer's authority. 1. General Conditions of Sale a. All persons on the premises of, or at a venue hired or borrowed by, the Auctioneer are there at their own risk. b. Such persons shall have no claim against the Auctioneer in respect of any accident, injury or damage howsoever caused nor in respect of cancellation or postponement of the sale. c. The Auctioneer reserves the right of admission which will be by registration at the front desk. d. For security reasons, bags are not allowed in the viewing area and must be left at the front desk or cloakroom. e. Persons handling lots do so at their own risk and shall make good all loss or damage howsoever sustained, such estimate of cost to be assessed by the Auctioneer whose decision shall be final. 2. Catalogue a. The Auctioneer acts as agent only and shall not be responsible for any default on the part of a vendor or buyer. -

English Counties

ENGLISH COUNTIES See also the Links section for additional web sites for many areas UPDATED 23/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] TRAVELINE SITES FOR ENGLAND GB National Traveline: www.traveline.info More-detailed local options: Traveline for Greater London: www.tfl.gov.uk Traveline for the North East: https://websites.durham.gov.uk/traveline/traveline- plan-your-journey.html Traveline for the South West: www.travelinesw.com Traveline for the West & East Midlands: www.travelinemidlands.co.uk Black enquiry line numbers indicate a full timetable service; red numbers imply the facility is only for general information, including requesting timetables. Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that a county or council might be showing on its web site. ENGLAND BEDFORDSHIRE BEDFORD Borough Council No publications Public Transport Team, Transport Operations Borough Hall, Cauldwell Street, Bedford MK42 9AP Tel: 01234 228337 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] www.bedford.gov.uk/transport_and_streets/public_transport.aspx COUNTY ENQUIRY LINE: 01234 228337 (0800-1730 M-Th; 0800-1700 FO) PRINCIPAL OPERATORS & ENQUIRY LINES: Grant Palmer (01525 719719); Stagecoach East (01234 220030); Uno (01707 255764) CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE Council No publications Public Transport, Priory House, Monks Walk Chicksands, Shefford SG17 5TQ Tel: 0300 3008078 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] -

Operators Route Contracts

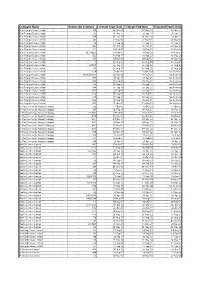

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

The Go-Ahead Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2019 1 Stable Cash Generative

Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 29 June 2019 Taking care of every journey Taking care of every journey Regional bus Regional bus market share (%) We run fully owned commercial bus businesses through our eight bus operations in the UK. Our 8,550 people and 3,055 buses provide Stagecoach: 26% excellent services for our customers in towns and cities on the south FirstGroup: 21% coast of England, in north east England, East Yorkshire and East Anglia Arriva: 14% as well as in vibrant cities like Brighton, Oxford and Manchester. Go-Ahead’s bus customers are the most satisfied in the UK; recently Go-Ahead: 11% achieving our highest customer satisfaction score of 92%. One of our National Express: 7% key strengths in this market is our devolved operating model through Others: 21% which our experienced management teams deliver customer focused strategies in their local areas. We are proud of the role we play in improving the health and wellbeing of our communities through reducing carbon 2621+14+11+7+21L emissions with cleaner buses and taking cars off the road. London & International bus London bus market share (%) In London, we operate tendered bus contracts for Transport for London (TfL), running around 157 routes out of 16 depots. TfL specify the routes Go-Ahead: 23% and service frequency with the Mayor of London setting fares. Contracts Metroline: 18% are tendered for five years with a possible two year extension, based on Arriva: 18% performance against punctuality targets. In addition to earning revenue Stagecoach: 13% for the mileage we operate, we have the opportunity to earn Quality Incentive Contract bonuses if we meet these targets. -

Somerset, England

Fleet Lists - Somerset, England This is our list of current open top buses in Somerset, England BATH - Bath Bus Company Ltd. (City Sightseeing Bath / Tootbus) [RATP Dev / Extrapolitan Sightseeing Group] Buses used for sightseeing tours under the Tootbus brand or City Sightseeing franchise. Fleet List FLEET NO REG NO CHASSIS / BODY LAYOUT LIVERY PREVIOUS KNOWN OWNER(S) 272 EU05 VBG (w) Volvo B7L / Ayats Bravo 1 City PO55/24F BATH NAVIGATOURS / BATH BUS COMPANY (red & black with large white New as part open top, 5/05 Tudor rose) 273 EU05 VBJ (w) Volvo B7L / Ayats Bravo 1 City PO55/24F Bath CitySightseeing / BATH BUS COMPANY (red with yellow flash) New as part open top, 5/05 274 EU05 VBK (w) Volvo B7L / Ayats Bravo 1 City PO55/24F CitySightseeing / BATH BUS COMPANY (red & black) New as part open top, 6/05 301 PN10 FNR Volvo B9TL / Optare Visionaire O51/31F CitySightseeing Bath (red with yellow flash and multicoloured graphics) (withdrawn, Transferred from Windsor to Bath, 2/18; transferred c.2/18) from Bath to Windsor, ?/14; new as open top, 4/10 374 EU05 VBM (w) Volvo B7L / Ayats Bravo 1 City O55/24F BATH BUS COMPANY SIGHTSEEING Serving Bath Since 1997 (red/cream) New as open top, 7/05 381 EU04 CPV (w) Volvo B7L / Ayats Bravo 1 City O55/24F Bath CitySightseeing / BATH BUS COMPANY (red with yellow flash) New as open top, 6/04 617 LJ07 XEU Volvo B9TL / East Lancs Visionaire PO49/31F Bath CitySightseeing (red with yellow flash & multicoloured graphics) Original London Sightseeing Tour Ltd. -

Russell Bailey Employment

Russell Bailey Employment The majority of Russell’s practice involves employment law and employment related issues including: All types of claims brought in the employment tribunal; unfair dismissal, TUPE issues, discrimination claims. Claims for wrongful termination. Injunctive relief arising from the enforcement of restrictive covenants. Year of Call: 1985 Claims for damages, accounts of profits and equitable relief arising from Clerks breaches of covenants and of confidentiality. Senior Practice Manager Claims by and against directors for breach of fiduciary obligations. James Parks Shareholder disputes including minority shareholder remedies. Practice Manager Martin Ellis Disputes arising under the Conduct of Employment Agencies and Employment Businesses Regulations 2003. Practice Group Clerk Adam Mountford Disputes about matters ancillary to the employment relationship such as James Ashford pensions and references. William Theaker Employee stress claims: Practice Director Claims by and against commercial agents under the 1993 Regulations. Tony McDaid Russell has been involved in advising and representing employers and Contact a Clerk employees for many years and, as appears from the list of reported Tel: +44 (0) 845 210 5555 cases below, he has a close involvement with the London transport Fax: +44 (0) 121 606 1501 industry. He has business experience independent of the Bar and is [email protected] adept at combining business acumen with legal expertise. RECOMMENDATIONS 'Russell Bailey’s broad practice includes stress at work and -

UNECE Tram and Metro Statistics Metadata Introduction File Structure

UNECE Tram and Metro Statistics Metadata Introduction This file gives detailed country notes on the UNECE tram and metro statistics dataset. These metadata describe how countries have compiled tram and metro statistics, what the data cover, and where possible how passenger numbers and passenger-km have been determined. Whether data are based on ticket sales, on-board sensors or another method may well affect the comparability of passenger numbers across systems and countries, hence it being documented here. Most of the data are at the system level, allowing comparisons across cities and systems. However, not every country could provide this, sometimes due to confidentiality reasons. In these cases, sometimes either a regional figure (e.g. the Provinces of Canada, which mix tram and metro figures with bus and ferry numbers) or a national figure (e.g. Czechia trams, which excludes the Prague tram system) have been given to maximise the utility of the dataset. File Structure The disseminated file is structured into seven different columns, as follows: Countrycode: These are United Nations standard country codes for statistical use, based on M49. The codes together with the country names, region and other information are given here https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/overview/ (and can be downloaded as a CSV directly here https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/overview/#). City: This column gives the name of the city or region where the metro or tram system operates. In many cases, this is sufficient to identify the system. In some cases, non-roman character names have been converted to roman characters for convenience. -

2021 Book News Welcome to Our 2021 Book News

2021 Book News Welcome to our 2021 Book News. As we come towards the end of a very strange year we hope that you’ve managed to get this far relatively unscathed. It’s been a very challenging time for us all and we’re just relieved that, so far, we’re mostly all in one piece. While we were closed over lockdown, Mark took on the challenge of digitalising some of Venture’s back catalogue producing over 20 downloadable books of some of our most popular titles. Thanks to the kind donations of our customers we managed to raise over £3000 for The Christie which was then matched pound for pound by a very good friend taking the total to almost £7000. There is still time to donate and download these books, just click on the downloads page on our website for the full list. We’re still operating with reduced numbers in the building at any one time. We’ve re-organised our schedules for packers and office staff to enable us to get orders out as fast as we can, but we’re also relying on carriers and suppliers. Many of the publishers whose titles we stock are small societies or one-man operations so please be aware of the longer lead times when placing orders for Christmas presents. The last posting dates for Christmas are listed on page 63 along with all the updates in light of the current Covid situation and also the impending Brexit deadline. In particular, please note the change to our order and payment processing which was introduced on 1st July 2020. -

Sowing the Seeds: Reconnecting London's Children with Nature

Sowing the SeedS Reconnecting London’S chiLdRen with natuRe novembeR 2011 Sowing the SeedS: Reconnecting London’S chiLdRen with natuRe copyRight Greater London Authority November 2011 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall, The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978-1-84781-471-5 Cover photo © WWT / photo by Debs Pinniger 3 Sowing the SeedS Reconnecting London’S chiLdRen with natuRe novembeR 2011 a RepoRt foR the London SuStainabLe deveLopment commission by tim gill Sowing the SeedS: Reconnecting London’S chiLdRen with natuRe contentS foRewOrd by John Plowman 5 executive SummaRy 7 one INTRODUCTION 13 two Why doeS chiLdRen’S engagement with natuRe matteR? 19 thRee London-baSed initiatives 23 four AnaLySiS: issueS, oppoRtunitieS and challenges 31 five RecommendationS: how to Reconnect London’S chiLdRen with natuRe 45 Six ConcLuSion 53 appendices 55 Appendix one: Fieldwork 55 Appendix two: Notes to Table 2 57 Appendix three: Measuring progress 59 Appendix four: Feedback on draft recommendations 63 Endnotes 69 5 foRewoRd by John Plowman Enormous progress has been made in recent This report is not a direct response to the rioting, years to improve the protection and provision of but it is relevant. It suggests that giving children green space in London. We need to ensure that access to nature promotes their mental and these green spaces do not lie idle. In investigating emotional well-being and may have a positive this, we decided to focus on the experiences effect on the behaviour of some children. While of children under 12.