7: in Bermondsey and Southwark I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iris Murdoch

Sunday 9th August 2020 www.rmmc.org.uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/tempRMMC/ Last week I shared the first part of the story of Arthur & Ada Salter that had impressed me as I walked the Thames Path. Part Two included today with Part One as reference if you want to re-read! Zoom Church Service Aug 9, 2020 6pm led by Cathy Smith https://astrazeneca.zoom.us/j/99881042054?pwd=UWU3QmE0VkNYNXBMNENLd2dkVmh4QT09 Meeting ID: 998 8104 2054. Password: 562655 0203 481 5237 or 0800 260 5801 7.30pm Monday 10th August The Prayer Course Session 1: Why Pray? https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84151838035?pwd=WFpkZTBjUW9MSW9VL2VMRDBYcU9iUT09 ID: 841 5183 8035 Passcode: 483980. Landline: 0203 051 2874 ‘Prayer is simply paying attention to God, which is a form of love.’ Iris Murdoch Unlike the last course I am thinking of this one being once or twice a month, and with a different aspect of prayer each time it will be easy for people to attend as many sessions as they like and are able. I look for- ward to us learning together. Living Streets and Highways We pray for the living streets in our neighbourhood, where our daily travels begin and end, and our love of God inspires our interactions with our neighbours. In our walks and our rides and our drives and our deliveries, God keep us safe and looking out for others. Somebody during the post-service coffee session on last Sunday's zoom call asked for more de- tails about the Highway Code Consultation. In summary the proposed changes support a heirar- chy of road-users, prioritising people who are most vulnerable to harm, starting with pedestrians, (especially children, older adults and people with disabilities) and stating more clearly how all oth- er road users can reduce the danger they may pose to others. -

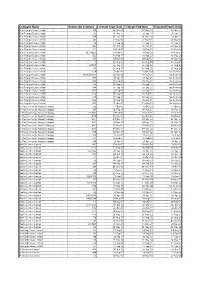

Operators Route Contracts

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

From Pacifist to Anti-Fascist? Sylvia Pankhurst and the Fight Against War and Fascism

FROM PACIFIST TO ANTI-FASCIST? SYLVIA PANKHURST AND THE FIGHT AGAINST WAR AND FASCISM Erika Marie Huckestein A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved By: Susan Pennybacker Emily Burrill Susan Thorne © 2014 Erika Huckestein ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erika Marie Huckestein: From Pacifist to Anti-Fascist? Sylvia Pankhurst and the Fight Against War and Fascism (Under the direction of Susan Pennybacker) Historians of women’s involvement in the interwar peace movement, and biographers of Sylvia Pankhurst have noted her seemingly contradictory positions in the face of two world wars: she vocally opposed the First World War and supported the Allies from the outbreak of the Second World War. These scholars view Pankhurst’s transition from pacifism to anti-fascism as a reversal or subordination of her earlier pacifism. This thesis argues that Pankhurst’s anti-fascist activism and support for the British war effort should not be viewed as a departure from her earlier suffrage and anti-war activism. The story of Sylvia Pankhurst’s political activism was not one of stubborn commitment to, or rejection of, a static succession of ideas, but one of an active engagement with changing politics, and confrontation with the new ideology of fascism, in a society still struggling to recover from the Great War. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 -

The Go-Ahead Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2019 1 Stable Cash Generative

Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 29 June 2019 Taking care of every journey Taking care of every journey Regional bus Regional bus market share (%) We run fully owned commercial bus businesses through our eight bus operations in the UK. Our 8,550 people and 3,055 buses provide Stagecoach: 26% excellent services for our customers in towns and cities on the south FirstGroup: 21% coast of England, in north east England, East Yorkshire and East Anglia Arriva: 14% as well as in vibrant cities like Brighton, Oxford and Manchester. Go-Ahead’s bus customers are the most satisfied in the UK; recently Go-Ahead: 11% achieving our highest customer satisfaction score of 92%. One of our National Express: 7% key strengths in this market is our devolved operating model through Others: 21% which our experienced management teams deliver customer focused strategies in their local areas. We are proud of the role we play in improving the health and wellbeing of our communities through reducing carbon 2621+14+11+7+21L emissions with cleaner buses and taking cars off the road. London & International bus London bus market share (%) In London, we operate tendered bus contracts for Transport for London (TfL), running around 157 routes out of 16 depots. TfL specify the routes Go-Ahead: 23% and service frequency with the Mayor of London setting fares. Contracts Metroline: 18% are tendered for five years with a possible two year extension, based on Arriva: 18% performance against punctuality targets. In addition to earning revenue Stagecoach: 13% for the mileage we operate, we have the opportunity to earn Quality Incentive Contract bonuses if we meet these targets. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

Red Flag Over Bermondsey - the Ada Salter Story

7.00 pm SATURDAY 5 DECEMBER 2015 RED FLAG OVER BERMONDSEY - THE ADA SALTER STORY Written and performed by Lynn Morris Directed by Dave Morris Where to start with Ada Salter? She was a true radical, campaigner for equal rights, socialist, republican, pacifist, environmentalist, trade union activist and a leading light in the transformation of the Bermondsey slums in the early part of the 20th century. Born into Methodism, she moved to London and became involved with the Bermondsey Settlement. She became a Quaker in 1914. She and her GP husband, Alfred Salter, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, living and working right in the heart of their community – and having to accept the tragic consequences of their choice. She and her husband were among the founders of the Independent Labour Party in Bermondsey. Ada herself broke through the glass ceiling of her time, becoming both the first woman councillor in London, and then the first woman mayor. Red Flag over Bermondsey explores the private and the public lives of Ada from 1909 until 1922, interwoven with her beloved Ira Sankey hymns and her passion for Handel. Further background about Ada (1866–1942) is to be found at www.quakersintheworld.org The performance lasts 65 minutes without interval. Lynn and Dave Morris are Journeymen theatre and they are committed to performing their work in any venue, theatre or non-theatre. Lynn and David attend Stourbridge Quaker Meeting. Visit the website at: www.journeymentheatre.com for details about the company, current and future productions, and reviews. Contact us at: [email protected] or [email protected] Admission FREE: All profits and donations from Red Flag over Bermondsey will be used to support our work with the Women’s Co-operative of Seir, West Bank, Palestine. -

Anticipated Acquisition by London and South Eastern Railway, a Wholly Owned Subsidiary of Govia Limited, of the Integrated Kent Rail Franchise

Anticipated acquisition by London and South Eastern Railway, a wholly owned subsidiary of Govia Limited, of the Integrated Kent Rail Franchise The OFT's decision on reference under section 33(1) given on 28 March 2006. Full text of decision published 4 April 2006. PARTIES 1. Govia Limited (Govia) is a rail franchise holding company. It was formed as a joint venture between The Go-Ahead Group Plc (Go-Ahead) and Keolis (UK) Limited (a subsidiary of Keolis SA), which have shareholdings in Govia of 65 per cent and 35 per cent respectively. Govia will acquire the Integrated Kent Rail Franchise through its wholly owned subsidiary, London and South Eastern Railway (LSER). 2. The Integrated Kent Rail Franchise (IKF) will include passenger rail services on the network currently operated by South Eastern Trains (SET), a subsidiary of the Strategic Rail Authority (SRA). IKF is a commuter network serving several areas around the South East of England, parts of Greater London and several London termini. IKF will also include new domestic high-speed services from London St Pancras, making use of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link. SET's turnover for the year ended 31 March 2005 was £443.3 million. TRANSACTION 3. Govia (through LSER) was named the preferred bidder for IKF on 30 November 2005. IKF is due to commence on 1 April 2006 and will run for six years, although the contract allows for an extension of two years if performance targets are met. Alternatively, in the event of a delay to the start of the new high speed services using the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, the franchise may be extended by two years. -

Item Captions Teachers Guide

SUFFRAGE IN A BOX: ITEM CAPTIONS TEACHERS GUIDE 1 1 The Polling Station. (Publisher: Suffrage Atelier). 1 Suffrage campaigners were experts in creating powerful propaganda images which expressed their sense of injustice. This image shows the whole range of women being kept out of the polling station by the law and authority represented by the policeman. These include musicians, clerical workers, mothers, university graduates, nurses, mayors, and artists. The men include gentlemen, manual workers, and agricultural labourers. This hints at the class hierarchies and tensions which were so important in British society at this time, and which also influenced the suffrage movement. All the women are represented as gracious and dignified, in contrast to the men, who are slouching and casual. This image was produced by the Suffrage Atelier, which brought together artists to create pictures which could be quickly and easily reproduced. ©Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection; Postcards 12 (385) Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford John Johnson Collection; Postcards 12 (385) 2 The late Miss E.W. Davison (1913). Emily Wilding Davison is best known as the suffragette who 2 died after being trampled by the King’s horse on Derby Day, but as this photo shows, there was much more to her story. She studied at Royal Holloway College in London and St Hugh’s College Oxford, but left her job as a teacher to become a full- time suffragette. She was one of the most committed militants, who famously hid in a cupboard in the House of Commons on census night, 1911, so that she could give this as her address, and was the first woman to begin setting fire to post boxes. -

Tfl Corporate Archive Top 20 Records

LT000605/005 - Description of the New Administrative Offices of the Underground Group of Companies By the late 1920s, the Underground Electric Railways Companies of London Ltd was anxious to house all of its ‘head office’ staff in one new purpose-built office block on the site of the old Metropolitan District Railway offices above St James’s Park station. The plans developed by Adams, Holden and Pearson, the architects commissioned by the Group, were radical: • 55 Broadway would be the tallest office building in London; • there would be a cruciform design - in place of the customary hollow rectangle format – which would offer staff more natural daylight in wings projecting from a central core housing lifts, staircases and essential services; and • Contemporary artists would be invited to sculpt decorative features directly onto the stone facade. As detailed in this reprint of a 1929 brochure about the building, 55 Broadway was constructed between 1927 and 1929. 700 reinforced concrete piles sunk to an average depth of 40 feet below basement level support the building. Nineteen load-bearing steel girders span the railway, and special insulation was used to reduce vibration from the trains. Above ground, the building was constructed around a steel girder skeleton and faced with 78,000 cubic feet of high quality Portland stone. The building has a bold appearance, enhanced by progressive stepping back above the sixth, eighth and ninth floors – giving an uneven pyramid effect. The clock tower, 174 feet high, has a similar stepped back effect. Granite for the ground floor came from Norway whilst the Travertine marble used in the interior came from Italy. -

New A4 Pages (Page 4)

HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE GP Practices Southwark PCT Premises Pharmacies 1 The New Mill Street Surgery (Dr A Campion) 1 Mary Sheridan House 1 A.R. Chemists 1 Wolseley Street, SE1 2BP 11-19 Thomas Street, SE1 9RY 176-178 Old Kent Road, SE1 5TY Tel: 020 7252 1817 2 Mabel Goldwin House Tel: 020 7703 4097 2 Parkers Row Family Practice (Dr S Bhatti) 49 Grange Walk, SE1 3DY 2 ABC Pharmacy 2 Wade House, Parkers Row, SE1 2DN 3 Woodmill Building 243 Southwark Park Road, SE16 3TS Tel: 020 7237 1517 Neckinger, SE16 3QN Tel: 020 7237 1659 3 Alfred Salter Medical Centre (Dr S Bhatti) 4 Bermondsey Health Centre 3 Amadi Chemist 6-8 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW 107 Abbey Street, SE1 3NP Tel: 020 7237 1857 5 John Dixon Clinic Tel: 020 7771 3863 4 The Grange Road Practice (Dr M Brooks) Prestwood House, 4 Bonamy Pharmacy Bermondsey Health Centre, 201-209 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 355 Rotherhithe New Road, 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW Bonamy Estate, SE16 3HF Tel: 020 7237 1078 6 Albion Street Health Centre 87 Albion Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 7JX Tel: 020 7231 9988 5 Bemondsey and Lansdowne Medical Mission, 5 Boots The Chemist PLC (Dr R Torry) 7 St Olave's Nursing Home 15 Ann Moss Way, SE16 2TJ Unit 11-13 Surrey Quays Shopping Centre, Decima Street, SE1 4QX Redriff Road, SE16 9SP 8 Surrey Docks Health Centre Enquiries: 020 7407 0752 Tel: 020 7252 0084 Appointments: 020 7403 36186 Downtown Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 1NP 6 Boots The Chemist PLC 9 Silverlock Clinic 6 -

Abaldwin Phd Final Text

University of Huddersfield Repository Baldwin, Anne Progress and patterns in the election of women as councillors, 1918 – 1938 Original Citation Baldwin, Anne (2012) Progress and patterns in the election of women as councillors, 1918 – 1938. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17514/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Progress and patterns in the election of women as councillors, 1918 – 1938 Anne Baldwin 19 March 2012 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements of a PhD, History, awarded by the University of Huddersfield. i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

Virginia Woolf's Three Guineas

FACULDADE DE LETRAS UNIVERSIDADE DO PORTO Marta Pereira Ferreira Correia 2º Ciclo de Estudos em Estudos Anglo-Americanos Variante de Estudos sobre Mulheres Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas: The Past, The Present and Into The Future 2013 Orientadora: Professora Doutora Ana Luísa Amaral Classificação: Ciclo de estudos: Dissertação: Versão definitiva 1 Acknowledgements (not necessarily in this order) To the women of my life who share their guineas and believe in education. To my partner and glamorous assistant for his patience and queer insights. To Rita, Guilherme and their parents for making life fun. To Orquídea and Manuela for helping me with my own personal struggle with the “Angel in the House.” To the Spanish lot who have no fairies. To my tutors and colleagues at FLUP for the “moments of being.” To Women in Black Belgrade for their availability and work. To Professor Ana Luísa Amaral for her guidance, her words and inspiration. 2 Abstract Three Guineas (1938) is Virginia Woolf’s most controversial work due to the themes it addresses and the angry tone in which it was written. Negative and positive reactions to this essay are amply documented and reflect the intended polemical nature of the text. The past of the essay, the background from where it arose, involves looking at history through Woolf’s eyes, the effects World War I had in her life and later the violent 1930’s in Europe which would lead to World War II, the rise of Fascism and the Spanish Civil War. The present of the text is twofold: it is the text itself, but also ideas discussed by contemporary scholars, which bring Three Guineas into our time.