The Eclectic Bicycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Interim Report and Unaudited Condensed Financial Statements for the Financial Half Year End 31St December, 2020

LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Interim Report and Unaudited Condensed Financial Statements For the financial half year end 31st December, 2020 Company Registration No. 499159 LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Table of Contents Page Management and Administration 1 General Information 2 Investment Manager’s Report 3-4 Condensed Statement of Financial Position 5-6 Condensed Statement of Comprehensive Income 7-8 Condensed Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Holders of Redeemable Participating Shares 9-10 Condensed Statement of Cash Flows 11-12 Notes to the Condensed Financial Statements 13-21 Los Angeles Capital Global Funds PLC - Los Angeles Capital Global Fund Schedule of Investments 22-31 Statement of Changes in the Portfolio 32-33 Appendix I 34 LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Management and Administration DIRECTORS REGISTERED OFFICE Ms. Edwina Acheson (British) 30 Herbert Street Mr. Daniel Allen (American) Dublin 2 Mr. David Conway (Irish)* D02 W329 Mr. Desmond Quigley (Irish)* Ireland Mr. Thomas Stevens (American) * Independent COMPANY SECRETARY LEGAL ADVISERS Simmons & Simmons Corporate Services Limited Simmons & Simmons Waterways House Waterways House Grand Canal Quay Grand Canal Quay Dublin Dublin D02 NF40 D02 NF40 Ireland Ireland INVESTMENT MANAGER CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS AND Los Angeles Capital Management and Equity STATUTORY AUDIT FIRM Research Inc.* Grant Thornton 11150 Santa Monica Boulevard 13-18 City Quay Suite 200 Dublin 2 Los Angeles D02 ED70 California 90025 Ireland USA * since 1st January, 2021 name has changed to Los Angeles Capital Management LLC MANAGEMENT COMPANY DEPOSITARY DMS Investment Management Services (Europe) Limited* Brown Brothers Harriman Trustee 76 Lower Baggot Street Services (Ireland) Limited Dublin 2 30 Herbert Street D02 EK81 Dublin 2 Ireland D02 W329 Ireland * since 29th July, 2020 ADMINISTRATOR, REGISTRAR AND DISTRIBUTOR TRANSFER AGENT LACM Global, Ltd. -

23Rd Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction

CATALOG PRICE $4.00 Michael E. Fallon / Seth E. Fallon COPAKE AUCTION INC. 266 Rt. 7A - Box H, Copake, N.Y. 12516 PHONE (518) 329-1142 FAX (518) 329-3369 Email: [email protected] Website: www.copakeauction.com 23rd Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction Featuring the David Metz Collection Also to include a selection of ephemera from the Pedaling History Museum, a Large collection of Bicycle Lamps from the Midwest and other quality bicycles, toys, accessories, books, medals, art and more! ************************************************** Auction: Saturday April 12, 2014 @ 9:00 am Swap Meet: Friday April 11th (dawn ‘til dusk) Preview: Thur. – Fri. April 10-11: 11-5pm, Sat. April 12, 8-9am TERMS: Everything sold “as is”. No condition reports in descriptions. Bidder must look over every lot to determine condition and authenticity. Cash or Travelers Checks - MasterCard, Visa and Discover Accepted First time buyers cannot pay by check without a bank letter of credit 17% buyer's premium (2% discount for Cash or Check) 20% buyer's premium for LIVE AUCTIONEERS Accepting Quality Consignments for All Upcoming Sales National Auctioneers Association - NYS Auctioneers Association CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Some of the lots in this sale are offered subject to a reserve. This reserve is a confidential minimum price agreed upon by the consignor & COPAKE AUCTION below which the lot will not be sold. In any event when a lot is subject to a reserve, the auctioneer may reject any bid not adequate to the value of the lot. 2. All items are sold "as is" and neither the auctioneer nor the consignor makes any warranties or representations of any kind with respect to the items, and in no event shall they be responsible for the correctness of the catalogue or other description of the physical condition, size, quality, rarity, importance, medium, provenance, period, source, origin or historical relevance of the items and no statement anywhere, whether oral or written, shall be deemed such a warranty or representation. -

“Btll^O^Hara the Piano Company, “We Are Ship- Phone 180 “Gloverlzed Soon the Company Adjourned to Dee

MONDAY; DECEMBER 27,1928 tmi. WWI3LOW MALI PAGE THREE Boxing Football Wrestling Golfing Baseball Basketball i m ¦ -inilfM——Hl—lI———'—Ml sfsdfsfd sfdfsf ‘I1 ¦!•••*•'!• 4- *!• *i* A Junior jazz band set is the A chemist of Dunedin, New Zea- Canada Entry * favorke novelty in the Christmas land, lias .discovered a process for DETROITERS ASK PARISIANS HOLD Tommy Herman Sport Briefs * Lumberjacks See toy displays at the Paris stores, cleaning wool badly stained by raising an appaling prospect for branding. Hitherto such staihs * BY THE * fond parents. have been ineradicable. THAT LANDIS BE SWIMMING RACE Beals Bretonnel * ASSOCIATED PRESS * Hard Game With ‘jl 4* ? ‘F 4* 4* 4* 4* 4* 4* 4* *F 4 1 4* CALLED COLD At Philadelphia Reggie McNamara, iron man of Colorado Quint UNFIT IN BITTER the Marathon on wheels, will em- Business and Professional bark for his 47th international DETROIT. Mich., Dec. 25 (AP) PARIS, Dec. 25 (AP) —In the PHILADELPHIA, Dec. 25 LAP) grind tomorrow on the Deutsch- FLAGSTAFF, Doc. 25.—1 f pres- Assistant County Prosecutor John bitter cold of the Christmas twi- —Tommy Herman, Philadelphia, land. Reggie has paired with Otto ent plans materialize, Coach E. IT. Directory of Parisians shiv- won the decision from c ¦ - - l'» "Watts 1tonight began drafting light, thousands judges’ Petri, for the forthcoming six-day “Swede” Lynch’s basketball team calling upon ered evening . Bretonnel, French' light- will be upon a 'ltttn owners of and smiled this at Fred race at Berlin. probably called to ABSTRACTS & TITLES HAIR DRESSING An/*Hear. league baseball clubs to the spectacle of a swimming race weight. -

Rafael Sabatini --^''The Tyrannicide ?? ^Uali^ Folk Ttrougliout Kentucl^ Tliat Name Crat Orcliard Stood for Good Food and Good Wliiskey

Ll^s CENTR/\L JUNE EDITION 1935 w.wv*" "• nil fnii I, I •T. 'tv:— I H a j Rafael Sabatini --^''The Tyrannicide ?? ^uali^ folk ttrougliout Kentucl^ tliat name Crat Orcliard stood for good food and good wliiskey Bubbling out of the limestone hills, down in the \\'ay—had a private supply shipped in by the barrel. It heart of the Blue Grass country, a sparkling spring wasn t a widely famous whiskey then. It wasn't even Hrst drew people to Crab Orchard. bottled or labeled. It was only in later years that it came They came to "take the waters," and,because they knew to be known as Crab Orchard u hiskey. good living and enjoved it, the local hotel strove to make The name Crab Orchard might never have leaped to their visit meinorable with such tempting Southern deli nationwide favor, except for one thing. cacies as barbecued squirrel,delectable It stood for a whiskey which was pohickory, or roast 'possum and can not only rich and mellow- not only died yams. made in the good old-fashioned way, Kentucky straight whiskey And there was something else—a straight as a string, hut uLo economical. straight b<mrbon whiskey, rich and rud Made the good old-fashioned way And suddenly, after repeal, all dy, ofa flavor which even the flower of America wanted such a whiske}'. Smooth and satisfying to taste old-time Kentucky's gentility praised. In a few brief weeks, the name and To find this particular whiskey, the Sold ot a price anyone can pay goijdness of Crab C)rchard whiskey Crab Orchard Springs Hotel had was on a miijiun tongues, and this searched fur and wide, and finally— one-time local fa\'orite is America's from a little distillery up Louisville fciitest-selling strcnght ivhtskey today. -

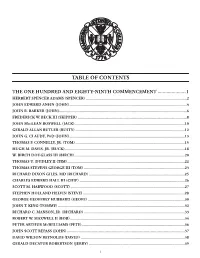

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY-NINTH COMMENCEMENT ......................1 HERBERT SPENCER ADAMS (SPENCER) ...................................................................................................2 JOHN EDWARD ANFIN (JOHN) ...................................................................................................................4 JOHN R. BARKER (JOHN) .............................................................................................................................6 FREDERICK W. BECK III (SKIPPER) ...........................................................................................................8 JOHN MACLEAN BOSWELL (JACK) ............................................................................................................10 GERALD ALLAN BUTLER (RUSTY) ...........................................................................................................12 JOHN G. CLAUDY, PHD (JOHN) .................................................................................................................13 THOMAS F. CONNELLY, JR. (TOM) ...........................................................................................................15 HUGH M. DAVIS, JR. (BUCK) .....................................................................................................................18 W. BIRCH DOUGLASS III (BIRCH) ............................................................................................................20 THOMAS U. DUDLEY II (TIM) ...................................................................................................................22 -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005 Peter Daerden Maurits Wynants Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren Contents Foreword 7 List of abbrevations 10 P A R T O N E : H E N R Y M O R T O N S T A N L E Y 11 JOURNALS AND NOTEBOOKS 11 1. Early travels, 1867-70 11 2. The Search for Livingstone, 1871-2 12 3. The Anglo-American Expedition, 1874-7 13 3.1. Journals and Diaries 13 3.2. Surveying Notebooks 14 3.3. Copy-books 15 4. The Congo Free State, 1878-85 16 4.1. Journals 16 4.2. Letter-books 17 5. The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, 1886-90 19 5.1. Autograph journals 19 5.2. Letter book 20 5.3. Journals of Stanley’s Officers 21 6. Miscellaneous and Later Journals 22 CORRESPONDENCE 26 1. Relatives 26 1.1. Family 26 1.2. Schoolmates 27 1.3. “Claimants” 28 1 1.4. American acquaintances 29 2. Personal letters 30 2.1. Annie Ward 30 2.2. Virginia Ambella 30 2.3. Katie Roberts 30 2.4. Alice Pike 30 2.5. Dorothy Tennant 30 2.6. Relatives of Dorothy Tennant 49 2.6.1. Gertrude Tennant 49 2.6.2. Charles Coombe Tennant 50 2.6.3. Myers family 50 2.6.4. Other 52 3. Lewis Hulse Noe and William Harlow Cook 52 3.1. Lewis Hulse Noe 52 3.2. William Harlow Cook 52 4. David Livingstone and his family 53 4.1. David Livingstone 53 4.2. -

Consolidated Contents of the American Genealogist

Consolidated Contents of The American Genealogist Volumes 9-85; July, 1932 - October, 2011 Compiled by, and Copyright © 2010-2013 by Dale H. Cook This index is made available at americangenealogist.com by express license of Mr. Cook. The same material is also available on Mr. Cook’s own website, among consolidated contents listings of other periodicals created by Mr. Cook, available on the following page: plymouthcolony.net/resources/periodicals.html This consolidated contents listing is for personal non-commercial use only. Mr. Cook may be reached at: [email protected] This file reproduces Mr. Cook’s index as revised August 22, 2013. A few words about the format of this file are in order. The first eight volumes of Jacobus' quarterly are not included. They were originally published under the title The New Haven Genealogical Magazine, and were consolidated and reprinted in eight volumes as as Families of Ancient New Haven (Rome, NY: Clarence D. Smith, Printer, 1923-1931; reprinted in three volumes with 1939 index Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1974). Their focus was upon the early families of that area, which are listed in alphabetical order. With a few exceptions this file begins with the ninth volume, when the magazine's title was changed to The American Genealogist and New Haven Genealogical Magazine and its scope was expanded. The title was shortened to The American Genealogist in 1937. The entries are listed by TAG volume. Each volume is preceded by the volume number and year(s) in boldface. Articles that are carried across more than one volume have their parts listed under the applicable volumes. -

Central-Eastern European Loess Sources Central- Och Östeuropeiska Lössursprung

Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2020: 8 Central-Eastern European Loess Sources Central- och östeuropeiska lössursprung Hanna Gaita DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2020: 8 Central-Eastern European Loess Sources Central- och östeuropeiska lössursprung Hanna Gaita Copyright © Hanna Gaita Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2020 Sammanfattning Central- och östeuropeiska lössursprung Hanna Gaita Klimatförändringar är idag en av våra högst prioriterade utmaningar. Men för att förstå klimatförändringar och kunna göra förutsägelser om framtiden är kunskap om tidigare klimat av väsentlig betydelse. Nyckelarkivet för tidigare klimatförändringar kan studeras genom så kallade lössavlagringar. Denna artikel undersöker lösskällor i Europa och hur dess avlagringar kan berätta för oss om olika ursprung med hjälp av olika geokemiska tekniker och metoder. Sekundära uppgifter om lössavlagringar och källor över Central- och Östeuropa har samlats in och undersökts för att testa några av de möjliga huvudsakliga stoftkällområdena för europeiska lössavlag- ringar som har föreslagits av andra forskare. Olika tekniker och metoder används för att undersöka lössediment när man försöker identifiera deras ursprung. Generellt kan tekniker och metoder delas in i några av följande geokemiska och analytiska parametrar: XRD (röntgendiffraktion) och XRF (röntgenfluorescensspektrometri), grundämnesför- hållanden, Sr-Nd isotopanalyser, zirkon U-Pb geokronologi, kombinerad bulk- och enkelkorns analyser såväl som mer statistiska tillvägagångssätt. Resultaten är baserade på tre huvudsakligen studerade artiklar och visar att det är mer troligt att lösskällor kommer från Högalperna och bergsområden, såsom Karpaterna, snarare än från glaciärer, som tidigare varit den mest relevanta idén. -

Service Rve Head O F the Fire D Epartm Ent and of a Crime Involving Moral Turpitude

Pate Eight THE HILLSIDE TIMES, FRIDAY, MARCH 4, 1927 LEGAL NOTICE suggestions that he may d$em proper. qualifications prescribed for members lation otUhe Department or of a co m given three days notice of the date of 1 be subjected to the penalty of, 110.00 mittee to be known as tbs Fir* O N - He shall keep a record of all business of the uniformed force, under Article II, mand oP % superior officer. trial and an opportunity to defend him- for each offense, mni.ee,mittee, methe met.first uiiyv«s..™appointed ***-*•man to do— tranaacteu by the Department and^ap- Section 12. known________ aa.1 ___them Chairman ..||,p .n nf of SB Hi.such IS fVASSt- Com self at a hearing of the Fire Commit 3— Any person who shall raise, create ERIFF’S SALE—-In Chancery of New prove all bills for^ expenses of the D e- Section 2—Each Volunteer Company tee. m ittee. .Xnartment. except those rendered for or continue a falsfe a arm o f fire or J e r s e y .__ ... ----- ------------- ~ tween December 1st and Decem AR TICLE V. operate a fire alarm box without rea- Sectlon 2—-All ordinance — ------ - and parts Of complainant, and Daniel Eben and Ber- fixed charges. ber 2ist of eac ordinances Inconsistent herewith are rha Eben, his w ife, et ala., defendants. Section I— General provisions— 1. Any »»n'«ble cause sha'l be subjected to a Section 6— He sh all keep an accurate and Assistant Foreman and Fire Mar person-rson wnowho snailshall during a lire dr I VS oftram_i2fi.0a. -

MBCUK LOG BOOK 5Th Edition March 2014

MBCUK LOG BOOK 5th Edition March 2014 MISSION STATEMENT TO PROVIDE PROFESSIONAL MOUNTAINBIKE COACHING, LEADER AND SKILLS AWARDS, IN A SAFE, ENJOYABLE AND LEARNING ENVIRONMENT DEVELOPING AND SHARING BEST PRACTICE TO ENABLE AWARD HOLDERS TO PASS ON THEIR EXPERIENCES TO THE WIDER CYCLING COMMUNITY Chip Rafferty (MA) Managing Director MBCUK 2 Contents Registration page 02 Foreword page 03 Matrix page 06 Syllabus page 07 • The Mountain Bike • Riding Types • Optimum Position • The Safe Cycle • Cycle Maintenance • Clothing and Equipment • On Road Safety Guidelines • Skills Test • Access and Conservation • Navigation • Planning your trip Cycling Disciplines page 20 Course Description page 23 MBCUK Mountain Biking Trail Grading page 29 Biking logbook page 30 Annexes • Risk Assessment Guidelines page 35 • Mountain Biking Risk Assessment page 36 • Vulnerability Guidelines page 37 • Skills Course Layout page 38 • Skills Test Score Card page 39 • Mountain Biking Route Card page 40 • Skill Levels page 41 • MBCUK Accident Report page 42 • Bike Checklist page 43 • Coaching Tips page 46 • Coach Checklist page 47 • Rider Profile page 48 • Course Questionnaire page 50 • ABCC Registration Renewal page 52 2 Registration Name Address Date of Birth Date of Enrolment approved Registration number sticker Training and Assessment Matrix and Record (See page 23) LEVEL LOCATION DATE TUTOR MBCUK sticker Training TL approved sticker Assessment TL approved sticker Training TTL approved sticker Assessment TTL sticker TTL Expedition Module TTL (E) sticker Training MBC approved sticker Assessment MBC approved sticker Tutor approved sticker First Aid Certificate Issued by Expires 3 MBCUK Mountain Bike Coach Awards Foreword The Mountain Bike Coaching UK MBCUK awards scheme exists to improve mountain bikers awareness of the knowledge and skills required to coach and lead on bikes with optimum safety education and comfort.