Target Switzerland by Stephen Halbrook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Military Cartridge Rifles and Bayonets

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY CARTRIDGE RIFLES AND BAYONETS The following table lists the most common international military rifles, their chambering, along with the most common bayonet types used with each. This list is not exhaustive, but is intended as a quick reference that covers the types most commonly encountered by today’s collectors. A Note Regarding Nomenclature: The blade configuration is listed, in parentheses, following the type. There is no precise dividing line between what blade length constitutes a knife bayonet vs. a sword bayonet. Blades 10-inches or shorter are typically considered knife bayonets. Blades over 12-inches are typically considered sword bayonets. Within the 10-12 inch range, terms are not consistently applied. For purposes of this chart, I have designated any blade over 12 inches as a sword bayonet. Country Rifle Cartridge Bayonet (type) Argentina M1879 Remington 11.15 x 58R Spanish M1879 (sword) Rolling-Block M1888 Commission 8 x 57 mm. M1871 (sword) Rifle M1871/84 (knife) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891 (sword) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. None Cavalry Carbine M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891/22 (knife) Engineer Carbine [modified M1879] M1891/22 (knife) [new made] M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 First Pattern (sword) M1909 Second Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 Second Cavalry Carbine Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) FN Model 1949 7.65 x 53 mm. FN Model 1949 (knife) FN-FAL 7.62 mm. NATO FAL Type A (knife) FAL Type C (socket) © Ralph E. Cobb 2007 all rights reserved Rev. -

3 Briarwood Lane Dept. of Religion Durham NH 03824 145 Bay State Rd

DAVID FRANKFURTER 3 Briarwood Lane Dept. of Religion Durham NH 03824 145 Bay State Rd. (603) 868-1619 Boston MA 02215 (603) 397-7136 (c) (617) 353-4431 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Princeton University (Religion — Religions of Late Antiquity), 1990 M.A., Princeton University (Religion — Religions of Late Antiquity), 1988 M.T.S., Harvard Divinity School (Scripture and Interpretation: New Testament), 1986 B.A., Wesleyan University (Religion), 1983, with High Honors in Religion and University Honors POSITIONS HELD Boston University: Department of Religion. Professor of Religion and William Goodwin Aurelio Chair in the Appreciation of Scripture, 2010 - present. Chair of Department, 2013 - . University of New Hampshire: Religious Studies Program, Department of History. Professor of History and Religious Studies, 2002-2010 ; Associate Professor of History and Religious Studies, 1998-2002; Assistant Professor of History and Religious Studies, 1995-98; Director of Religious Studies Program, 1997- 2010. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University: Lillian Gollay Knafel Fellow, 2007-08 Brown University: Department of Religious Studies. Visiting Professor of Religious Studies, Fall 2006. Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton NJ: School of Historical Studies. Fairchild Fellow, 1993-95 The College of Charleston: Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies. Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, 1990-95. University of Michigan: Department of Near Eastern Studies. Adjunct Lecturer in New Testament, 1989. FELLOWSHIPS, HONORS, AND -

Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence in Interwar France

Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence in Interwar France Richard Sonn University of Arkansas On a clear, beautiful day in the center of the city of Paris I performed the first act in front of the entire world. 1 Scholom Schwartzbard, letter from La Santé Prison In this letter to a left-wing Yiddish-language newspaper, Schwartzbard explained why, on 25 May 1926, he killed the former Hetman of the Ukraine, Simon Vasilievich Petliura. From 1919 to 1921, Petliura had led the Ukrainian National Republic, which had briefly been allied with the anti-communist Polish forces until the victorious Red Army pushed both out. Schwartzbard was a Jewish anarchist who blamed Petliura for causing, or at least not hindering, attacks on Ukrainian Jews in 1919 and 1920 that resulted in the deaths of between 50,000 and 150,000 people, including fifteen members of Schwartzbard's own family. He was tried in October 1927, in a highly publicized court case that earned the sobriquet "the trial of the pogroms" (le procès des pogroms). The Petliura assassination and Schwartzbard's trial highlight the massive immigration into France of central and eastern European Jews, the majority of working-class 1 Henry Torrès, Le Procès des pogromes (Paris: Editions de France, 1928), 255-7, trans. and quoted in Felix and Miyoko Imonti, Violent Justice: How Three Assassins Fought to Free Europe's Jews (Amherst, MA: Prometheus, 1994), 87. 392 Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence 393 background, between 1919 and 1939. The "trial of the pogroms" focused attention on violence against Jews and, in Schwartzbard's case, recourse to violence as resistance. -

" Triumph of the Will": a Limit Case for Effective-Historical Consciousness?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 611 CS 508 146 AUTHOR Schwartzman, Roy TITLE "Triumph of the Will": A Limit Case for Effective-Historical Consciousness? PUB DATE Jan 93 NOTE 27p.; Paper presented at the Annual Florida State University Conference on Literature and Film (18th, Tallahassee, FL, January 1993). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports Evaluative /Feasibility (142) Guid'ts Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Audience Awareness; *Critical Viewing; Documentaries; Film Criticism; *Film Study; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; Media Research; Nazism; *Persuasive Discourse; Propaganda IDENTIFIERS Film Genres; Film History; Film Viewing; Gadamer (Hans Georg); Germany; *Triumph of the Will ABSTRACT A film presented as factual may permit critical responses that question its purported factual objectivity and political neutrality. In class, Hans-Georg Gadamer's concept 3f effective-historical consciousness can be used to evaluate the allegedly propagandistic messages in Leni Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will." Analysis of this 1934 film reveals how it reinforced racial doctrines propagated by the Nazis and by scientists who sympathized with these racial views. Somewhat paradoxically, Riefenstahl's film may be considered a harbinger of twogenres in film whose essences seem contradictory: documentary and propaganda. "Triumph of the Will" contains no narration whatsoever after brief introductory remarks. Nat verbalized, these remarks are printedon successive screens in short phrases. This lack of narration reduces the critical distance between viewer and event. The opening scene features Adolf Hitler emerging from a plane to grace Nuremberg with his presence, and to rescue and transform Germany. -

And Other Targeted Minorities in the Third Reich Week 2 Unit Learning Ou

WEEK 2 Prewar Persecution of “Enemies of the State” and Other Targeted Minorities in the Third Reich Prepared by Tony Joel and Mathew Turner Week 2 Unit Learning Outcomes ULO 1. evaluate in a reflective and critical manner the consequences of racism and prejudice ULO 3. synthesise core historiographical debates on how and why the Holocaust occurred Introduction This learning module is divided into a series of seven mostly short sections all of which are linked by the common theme of German victim groups who were ostracised and persecuted by their own government when living under Nazism. We start this week by examining the Nazi concept of supposed “Aryan” superiority and the creation of a national socialist “people’s community” or what the Nazis termed their ideal Volksgemeinschaft. Section 2 explores theories of Nazi “racial hygiene” and eugenics, which provided a pseudoscientific framework for Nazi racial theories including the identification of “undesirables” (Jews and others) who were classified as not belonging to the Volksgemeinschaft. Section 3 (the lengthiest this week) investigates the persecution of Jews living in the Third Reich, particularly in the prewar period 1933-39 but also up to 1941. Section 4 considers how German Jews responded to this persecution, both “officially” and privately. Section 5 outlines the Nazi system of concentration camps, used to intimidate and imprison political opponents and other individuals considered to be “enemies of the state.” The section reinforces the important point that, although they were included among the targets, Jews were by no means the main priority during the prewar period. Section 6 looks at the Nazi program of forced sterilisation introduced as early as July 1933, which provided Nazi doctors with the legal means to carry out the sterilisation of individuals who, according to racial “science,” threatened the purity of the “Aryan race.” Sterilisation victims included Germans with hereditary illnesses, mental illnesses, or perceived physical and intellectual disabilities. -

2018 National Trophy Rifle Matches Results

2018 National Trophy Rifle Matches Results Camp Perry, Ohio www.TheCMP.org CMP’s 2018 National Pistol and Rifle Matches Start Off With a Bang at Camp Perry By Ashley Brugnone, CMP Writer CAMP PERRY, Ohio – When most think of summertime in Port Clinton, they think beaches, boating and, in gen- eral, having an unlimited amount of fun in the water and on the shore. For others, summer in Port Clinton still means fun on the shoreline, but fun gearing up for the incomparable World Series of Shoot- ing Sports at Camp Perry. The National Trophy Rifle and Pistol Matches has welcomed millions of competitors and guests to the Port Clin- ton area since 1907. Embracing competi- tors from across the country, (and even some from countries like England and Australia, among others), the National Match event features a variety of rifle and pistol competitions and clinics for marksmen ranging from some of today’s most prestigious shots to those who have never pulled a trigger. The National Matches are held to promote competition and excellence, while also striving to Maj. Gen. LeMasters fired this year’s ceremonial First Shot. teach marksmanship safety and funda- mentals to the old, young and everything in between. The annual event at the Camp Perry National Guard Training Base is hosted by the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP), with help from the Ohio National Guard. Continued on Page 4 Above left: Members of the 555th Honors Detachment color guard from Wooster, Ohio, stood resiliently during the ceremony. Above right: A trio of historic cannons blasted pillows of white puffy smoke to kick off the First Shot Ceremony. -

Appenzell-Ausserrhoder Staatskalender

Appenzell-Ausserrhoder Staatskalender Autor(en): [s.n.] Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Appenzeller Kalender Band (Jahr): 158 (1879) PDF erstellt am: 26.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-373735 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Eidgenössische Behörden. B u n o c s r a t h. Gcb, 1833 Joseph Bläsi von Aedermannsdorf (Solothurn). (Amtsperiode: 1, Jan, 187« bis 31, Dez, 1878,! 1827 Heinrich Stamm von Thayngen (Schaffhausen). Erw. Geb, 1822 Dr. Jb. Dubs von Affoltern a. A. (Zürick) 1364 Dr. Karl Schenk von Signau (Bern) 1839 Hans Weber von Oberflachs (Aargau). Präsident für 1378 1823 1823 Jean Broye von Freiburg. -

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss By

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss by Patricia Josette Prokert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jane F. Fulcher, Co-Chair Professor Jason D. Geary, Co-Chair, University of Maryland School of Music Professor Charles H. Garrett Professor Patricia Hall Assistant Professor Kira Thurman Patricia Josette Prokert [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4891-5459 © Patricia Josette Prokert 2020 Dedication For my family, three down and done. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family― my mother, Dev Jeet Kaur Moss, my aunt, Josette Collins, my sister, Lura Feeney, and the kiddos, Aria, Kendrick, Elijah, and Wyatt―for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my educational journey. Without their love and assistance, I would not have come so far. I am equally indebted to my husband, Martin Prokert, for his emotional and technical support, advice, and his invaluable help with translations. I would also like to thank my doctorial committee, especially Drs. Jane Fulcher and Jason Geary, for their guidance throughout this project. Beyond my committee, I have received guidance and support from many of my colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance. Without assistance from Sarah Suhadolnik, Elizabeth Scruggs, and Joy Johnson, I would not be here to complete this dissertation. In the course of completing this degree and finishing this dissertation, I have benefitted from the advice and valuable perspective of several colleagues including Sarah Suhadolnik, Anne Heminger, Meredith Juergens, and Andrew Kohler. -

More and Less Deserving Refugees: Shifting Priorities in Swiss Asylum Policy from the Interwar Era to the Hungarian Refugee Crisis of 1956

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 More and Less Deserving Refugees: Shifting Priorities in Swiss Asylum Policy from the Interwar Era to the Hungarian Refugee Crisis of 1956 Ludi, Regula DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009414528261 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-105643 Journal Article Originally published at: Ludi, Regula (2014). More and Less Deserving Refugees: Shifting Priorities in Swiss Asylum Policy from the Interwar Era to the Hungarian Refugee Crisis of 1956. Journal of Contemporary History, 49(3):577- 598. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009414528261 Article Journal of Contemporary History 2014, Vol. 49(3) 577–598 More and Less Deserving ! The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Refugees: Shifting DOI: 10.1177/0022009414528261 Priorities in Swiss jch.sagepub.com Asylum Policy from the Interwar Era to the Hungarian Refugee Crisis of 1956 Regula Ludi Universita¨tZu¨rich, Switzerland Abstract In 1956, thousands of Hungarian refugees found a warm welcome in Switzerland. Swiss students took to the streets to demonstrate against Soviet repression of the Hungarian uprising. However, the upsurge of public sympathy for the refugees barely covered up recent controversy in Switzerland over asylum policy during the years of fascism and the Second World War. In 1954, only two years before the Hungarian refugee crisis, newly released German foreign policy documents had revealed Swiss involvement in the introduction of the ‘J’-stamp in 1938 to mark the passports of German (and formerly Austrian) Jews, making it easier for Swiss immigration officials to identify Jews as (undesirable) refugees. -

Stk No Mfg Model Finish Type Cal Ask 41983 American Bull Dog 2.5In

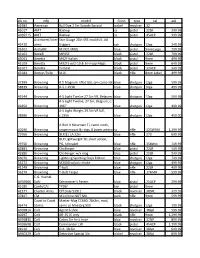

stk no mfg model finish type cal ask 41983 American Bull Dog 2.5in Suicide Special nickel revolver .32 42017 AMT Backup ss pistol .22LR 299.99 A939715 AMT Backup ss pistol .45ACP 399.99 Aramberri/Inter Star Guage 28in SXS mod/full, dbl 42470 arms triggers cch shotgun 12ga 249.99 35302 Astra/IIC M1921 (400) blue pistol 9mmLargo 299.99 43163 Benelli MP95E black pistol .22LR 799.99 43041 Beretta M92F Italian black pistol 9mm 499.99 43109 Beretta M92FS w/2-10 & 6 Hi-cap Mags black pistol 9mm 649.99 43107 Beretta Tomcat black pistol .32ACP 349.99 43184 Bertier/Tulle M16 black rifle 8mm Lebel 499.99 37399 Browning A 5 Magnum rifled bbl, syn camo stk blue shotgun 12ga 599.99 38839 Browning A-5 c.1938 blue shotgun 16ga 499.99 41944 Browning A-5 Light Twelve 27.5in VR, Belgium blue shotgun 12ga 599.99 A-5 Light Twelve, 27.5in, Belgium, c. 42850 Browning 1967 blue shotgun 12ga 499.99 A-5 Light Weight 29.5in VR full, 38986 Browning c.1956 blue shotgun 12ga 450.00 A-Bolt II Mountain Ti, camo stock, 40196 Browning scope mount & rings, 8 boxes ammo ss rifle .325WSM 1,399.99 29766 Browning BLR 81 LA 22in blue rifle .270 699.99 BLR Lightweight '81 short action, 29756 Browning PG, Schnabel blue rifle .358Win 749.99 42881 Browning Challenger blue pistol .22LR 549.99 42880 Browning Challenger w/x mag blue pistol .22LR 549.99 43070 Browning Lightning Sporting Clays Edition blue shotgun 12ga 749.99 35272 Browning M2000 w/poly choke blue shotgun 12ga 499.99 41249 Browning T-bolt blue rifle .22LR 499.99 36279 Browning T-Bolt Target blue rifle .17HMR 599.99 C.G. -

The Peace Conference of Lausanne (1922-1923)

Bern 1923 - 2008 With the kind support of: Mrs Ionna Ertegiin Mrs Selma Goksel Tiirkiye I~ Bankasi Anadolu Ajans1 Thanks to: Onur Ozc;:eri (Research, text and layout) Agathon Aerni (research) Tuluy Tanc;: (editing) © Embassy of Turkey, Bern 85 years of representation of the Republic of Turkey in Switzerland (1923-2008) The Embassy of the Republic of Turkey, Bern ~u6tic offJ'urk,ey rrfie (Jlresufent It is no coincidence that the Republic of Turkey purchased its first Embassy premises abroad, in Switzerland's capital, Bern, to establish the seat of its diplomatic representation. The negotiation of a peace treaty and its successful outcome took the shape of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. The Treaty of Lausanne left an indelible mark in our memory. The aspiration of the Turkish nation to live as a free and independent people is thus anchored in Switzerland, a land that earned the reputation for fairness, equity and justice. The subsequent adoption in 1926 of a Civil Code based on the Swiss example, the Montreux Convention negotiated in 1936 in Switzerland giving full sovereignty on the Turkish Straits and other events have solidified this perception. I am therefore particularly pleased that the roots of the friendship bonds between Turkey and Switzerland and the main events associating Switzerland to Turkey have been compiled in a book. The book also illustrates the reciprocal attention and like minded approaches of both Turkey and Switzerland to further promote bilateral relations between two democracies and to facilitate the realization of aspirations of peace. I would like to express my thanks to the President of the Swiss Confederation, His Excellency Pascal Couchepin and to all who have contributed to the realization of this book. -

Nachlass Von Bundesrat Rudolf Minger (1881–1955)

Eidgenössisches Departement des Innern EDI Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv BAR Nachlass von Bundesrat Rudolf Minger (1881–1955) Der Nachlass von Rudolf Minger (1881–1955) bietet vielfältige Quellen über das Leben und Werk des bernischen und eidgenössischen Parlamentariers, Bundesrats und alt Bundesrats. Er dokumentiert politische, wirtschaftliche und soziale Herausforderungen, mit denen sich Minger beschäftigt hatte – insbesondere in der Landwirtschaft und der Landesverteidigung. Die vorliegende Publikation bildet eine Bestandsanalyse. Während die Metadaten in der Archivdaten- bank die Titel der einzelnen Dossiers und deren Grenzdaten auflisten, wird der Bestand im publizier- ten Inventar kapitelweise zusammenfassend charakterisiert und kommentiert und damit in den histori- schen Zusammenhang eingeordnet. Bestellen der Unterlagen Sämtliche aufgeführten Unterlagen sind heute online recherchier- und bestellbar. Allerdings hat sich die Schreibweise der Signaturen geändert. In diesem Bestand ist die Archivnummer Bestandteil der Signatur. Sie müssen den Signaturstamm J1.108#1000/1275# mit der kursiv angegebenen Nummer (z. B. 500) ergänzen. Kombinieren Sie wenn nötig weitere Suchfelder, um einen Eintrag aus dem Inventar zu eruieren (z. B. «Titel» oder «Zeitraum»). Bei mehreren Ergebnissen achten Sie auf den entsprechenden Entstehungszeitraum. Zum Beispiel: Wenn Sie ein Dossier nicht finden, wenden Sie sich an die Beratung. Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv Archives fédérales suisses Archivio federale svizzero Inventare Inventaires Inventari Der Nachlass