The Sensuous Cinema of Wong Kar-Wai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Wendy Gan Hong Kong University Press the University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong

Wendy Gan Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2005 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-962-209-743-8 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Pre-Press Limited in Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Contexts: Independent Filmmaking and Hong Kong 11 Cinema 3 Contexts: Social Realism in Hong Kong Cinema 25 4 The Representation of the Mainland Chinese Woman 43 in Durian Durian 5 Durian Adrift: The Contiguities of Identity in Durian 59 Durian ● vi CONTENTS 6 The Prostitute Trilogy So Far 81 7 Conclusion 91 Notes 97 Filmography 103 Bibliography 107 ●1 Introduction Durian Durian is not the film one immediately thinks of when the name of Hong Kong film director Fruit Chan is brought up. The stunning success, both locally and internationally, of his low-budget debut as an independent director, Made in Hong Kong, has ensured that Chan’s reputation will always be tied to that film. Yet Durian Durian has much to offer the lover of Hong Kong cinema and the admirer of Fruit Chan’s work. A post-1997 film set both in Hong Kong and mainland China, with mainland Chinese protagonists, the film is a fine example of a Hong Kong tradition of socially sensitive realist films focused on the low-caste outsider, and is the result of a maturing director’s attempt to articulate the new, often still contradictory, realities of ‘one country, two systems’ in action. -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

The Whistleblowers

A U S F I L M Australian Familiarisation Event Mathew Tang Producer Mathew Tang began his career in 1989 and has since worked on over 30 feature films, covering various creative and production duties that include assistant directing, line-producing, writing, directing and producing. In 1999, Mathew debuted as a screenwriter on The Kid, a film that went on to win Best Supporting Actor and Actress in the Hong Kong Film Awards. In 2005, he wrote, edited and directed his debut feature B420 which received The Grand Prix Award at the 19th Fukuoka Asian Film Festival and Best Film at the 4th Viennese Youth International Film Festival in 2007. Mathew served as Associate Producer and Line Producer on Forbidden Kingdom and oversaw the Hollywood blockbuster’s entire production in China. In 2008 and 2009 he was Vice President of Celestial Pictures. From 2009- 2012, he was the Head of Productions at EDKO Films Ltd. In the summer of 2012, he founded Movie Addict Productions and the company produced four movies. Mathew is currently an Invited Executive Member of the Hong Kong Screenwriters’ Guild and a Panel Examiner of the Hong Kong Film Development Council. Johnny Wang Line Producer Johnny Wang started working for the movie industry in 1989 and by the year 2002, he started working at Paramount Studios on the project Tomb Raider 2 as production supervisor on location in Hong Kong. Since then, he has line produced 20 movies in Hong Kong, China and other locations around the world. Johnny has been an executive board member of the HKMPEA (Hong Kong Movie Production Executives Association) for more than four years. -

Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐Wai's Days Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PDXScholar PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal Volume 3 Issue 1 Identity, Communities, and Technology: On the Article 18 Cusp of Change 2009 Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 Julie Nakama Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Nakama, Julie (2009) "Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046," PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 18. 10.15760/mcnair.2009.127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Portland State University McNair Research Journal 2009 Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 by Julie Nakama Faculty Mentor: Mark Berrettini Citation: Nakama, Julie. Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046. Portland State University McNair Scholars Online Journal, Vol. 3, 2009: pages [127‐153] McNair Online Journal Page 1 of 27 Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 Julie Nakama Mark Berrettini, Faculty Mentor Wong Kar-wai is part of a generation of Hong Kong filmmakers whose work can be seen in response to two pivotal events in Hong Kong, the 1984 signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration detailing Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997 and the events of Tiananmen Square in 1989. -

Hist Art 3901 Course Change.Pdf

COURSE CHANGE REQUEST Last Updated: Haddad,Deborah Moore 3901 - Status: PENDING 12/31/2020 Term Information Effective Term Summer 2021 Previous Value Summer 2017 Course Change Information What change is being proposed? (If more than one, what changes are being proposed?) to offer a 100% distance learning offering of 3901 What is the rationale for the proposed change(s)? The course ran in AU20 during the pandemic and received a course assurance. The department would like the flexibility to run the course as a "DL" course in the future. What are the programmatic implications of the proposed change(s)? (e.g. program requirements to be added or removed, changes to be made in available resources, effect on other programs that use the course)? The department will be able to offer the course as "DL" during the summer (with college approval) and students who are off-campus during the summer will be able to take the course and further their degree requirements. The course is also a Film Studies major course option and it will help students in that program as well. Is approval of the requrest contingent upon the approval of other course or curricular program request? No Is this a request to withdraw the course? No General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area History of Art Fiscal Unit/Academic Org History of Art - D0235 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Undergraduate Course Number/Catalog 3901 Course Title World Cinema Today Transcript Abbreviation World Cinema Course Description An introduction to the art of international cinema today, including its forms and varied content. -

Zz027 Bd 45 Stanley Kwan 001-124 AK2.Indd

Statt eines Vorworts – eine Einordnung. Stanley Kwan und das Hongkong-Kino Wenn wir vom Hongkong-Kino sprechen, dann haben wir bestimmte Bilder im Kopf: auf der einen Seite Jacky Chan, Bruce Lee und John Woo, einsame Detektive im Kampf gegen das Böse, viel Filmblut und die Skyline der rasantesten Stadt des Universums im Hintergrund. Dem ge- genüber stehen die ruhigen Zeitlupenfahrten eines Wong Kar-wai, der, um es mit Gilles Deleuze zu sagen, seine Filme nicht mehr als Bewe- gungs-Bild, sondern als Zeit-Bild inszeniert: Ebenso träge wie präzise erfährt und erschwenkt und ertastet die Kamera Hotelzimmer, Leucht- reklamen, Jukeboxen und Kioske. Er dehnt Raum und Zeit, Aktion in- teressiert ihn nicht sonderlich, eher das Atmosphärische. Wong Kar-wai gehört zu einer Gruppe von Regisseuren, die zur New Wave oder auch Second Wave des Hongkong-Kinos zu zählen sind. Ihr gehören auch Stanley Kwan, Fruit Chan, Ann Hui, Patrick Tam und Tsui Hark an, deren Filme auf internationalen Festivals laufen und liefen. Im Westen sind ihre Filme in der Literatur kaum rezipiert worden – und das will der vorliegende Band ändern. Neben Wong Kar-wai ist Stanley Kwan einer der wichtigsten Vertreter der New Wave, jener Nouvelle Vague des Hongkong-Kinos, die ihren künstlerischen und politischen Anspruch aus den Wirren der 1980er und 1990er Jahre zieht, als klar wurde, dass die Kronkolonie im Jahr 1997 von Großbritannien an die Volksrepublik China zurückgehen würde. Beschäftigen wir uns deshalb kurz mit der historischen Dimension. China hatte den Status der Kolonie nie akzeptiert, sprach von Hong- kong immer als unter »britischer Verwaltung« stehend. -

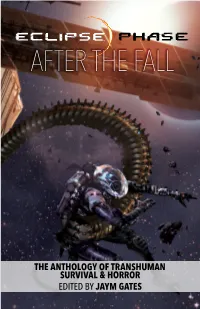

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

3D423bbe0559a0c47624d24383

BENDS straddles the Hong Kong- Shenzhen border and tells the story of ANNA, an affluent housewife and FAI, her chauffeur, and their unexpected friendship ABOUT as they each negotiate the pressures of Hong Kong life and the city’s increasingly complex relationship to mainland China. Fai is struggling to find a way to bring his THE pregnant wife and young daughter over the Hong Kong border from Shenzhen to give birth to their second child, even though he crosses the border easily every FILM day working as a chauffeur for Anna. Anna, in contrast, is struggling to keep up the facade of her ostentatious lifestyle into which she has married, after the sudden disappearance of her husband amid financial turmoil. Their two lives collide in a common space, the car. PRODUCTION NoteS SHOOT LOCATION: Hong Kong TIMELINE: Preproduction, July/August 2012 Principal Photography, September/October 2012 (23 days) Completion, Spring 2013 PREMIERE: Cannes Film Festival 2013, Un Certain Regard (Official Selection) LANGUAGE: Cantonese & Mandarin FORMAT: HD, Colour LENGTH: 92 minutes THE CaST ANNA - Lead Female Role Carina Lau 劉嘉玲 SelecTED FILMOGRAPHY: Detective Dee and the Mystery Phantom Flame Let the Bullets Fly 2046 Flowers of Shanghai Ashes of Time Days of Being Wild FAI - Lead Male Role Chen Kun 陳坤 SelecTED FILMOGRAPHY: Painted Skin I & II, Rest On Your Shoulder, Flying Swords of Dragon Gate 3D Let the Bullets Fly Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress Writer/Director Flora Lau 劉韻文 Cinematographer Christopher Doyle (H.K.S.C.) 杜可風 A Very Special Thanks To William Chang Suk Ping 張叔平 Flora was born and raised in Hong Kong. -

Feff Press Kit

PRESS RELEASES, FILM STILLS & FESTIVAL PICS AND VIDEOS TO DOWNLOAD FROM WWW.FAREASTFILM.COM PRESS AREA Press Office/Far East Film Festival 19 Gianmatteo Pellizzari & Ippolita Nigris Cosattini +39/0432/299545 - +39/347/0950890 [email protected] - [email protected] Video Press Office Matteo Buriani +39/345/1821517 – [email protected] 21/29 April 2017 – Udine – Teatro Nuovo and Visionario FAR EAST FILM FESTIVAL 19: THE POWER OF ASIA! The irresistible road movie Survival Family opens the #FEFF19 on Friday the 21 st of April: a packed programme which testifies to the incredible vitality (both productive and creative) of Asian cinema. 83 titles selected from almost a thousand seen, and 4 world premiers, including Herman Yau's high-octane thriller Shock Wave , which will close the nineteenth edition. Press release of the 13 th of April 2017 For immediate release UDINE - Who turned out the lights? Nobody did, and the fuses haven't blown. And no, it's not even a power cut. Electricity has just suddenly ceased to exist, so the Suzuki family must now very quickly learn the art of survival: and facing a global blackout is not exactly a walk in the park! It's with the world screeching to a halt of the irresistible Japanese road movie Survival Family that the highly anticipated Far East Film Festival 19 opens: not just because Yaguchi Shinobu' s wonderful comedy is the festival's starting pistol on Friday the 21 st of April, but also for a question of symmetry: just like the blackout in Survival Family , the FEFF is an interruption . -

The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming-Liang's Goodbye, Dragon Inn

Screening Today: The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming-liang's Goodbye, Dragon Inn Elizabeth Wijaya Discourse, Volume 43, Number 1, Winter 2021, pp. 65-97 (Article) Published by Wayne State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/790601 [ Access provided at 26 May 2021 21:04 GMT from University of Toronto Library ] Screening Today: The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming- liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn Elizabeth Wijaya Waste is the interface of life and death. It incarnates all that has been rendered invisible, peripheral, or expendable to history writ large, that is, history as the tale of great men, empire, and nation. —Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother (2006) A film operates through what it withdraws from the visible. —Alain Badiou, Handbook of Inaesthetics (2004) 1. Goodbye, Dragon Inn in the Time After Where does cinema begin and end? There is a series of images in Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), directed by Tsai Ming-liang, that contain the central thesis of this essay (figure 1). In the first image of a canted wide shot, Chen Discourse, 43.1, Winter 2021, pp. 65–97. Copyright © 2021 Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309. ISSN 1522-5321. 66 Elizabeth Wijaya Figure 1. The Ticket Lady’s face intercepting the projected light in Good- bye, Dragon Inn (Homegreen Films, 2003). Shiang-Chyi’s character of the Ticket Lady is at the lower edge of the frame, and with one hand on the door of a cinema hall within Fuhe Grand Theater, she looks up at the film projection of a martial arts heroine in King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1967).