Ohio Historic Preservation Tax Credit, 2015 Comprehensive Report, Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 14, 2016

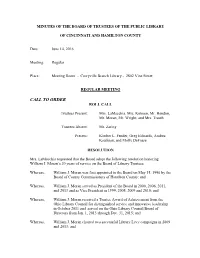

MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE PUBLIC LIBRARY OF CINCINNATI AND HAMILTON COUNTY Date: June 14, 2016 Meeting: Regular Place: Meeting Room - Corryville Branch Library - 2802 Vine Street REGULAR MEETING CALL TO ORDER ROLL CALL Trustees Present: Mrs. LaMacchia, Mrs. Kohnen, Mr. Hendon, Mr. Moran, Mr. Wright, and Mrs. Trauth Trustees Absent: Mr. Zaring Present: Kimber L. Fender, Greg Edwards, Andrea Kaufman, and Molly DeFosse RESOLUTION Mrs. LaMacchia requested that the Board adopt the following resolution honoring William J. Moran’s 20 years of service on the Board of Library Trustees. Whereas, William J. Moran was first appointed to the Board on May 15, 1996 by the Board of County Commissioners of Hamilton County; and Whereas, William J. Moran served as President of the Board in 2000, 2006, 2011, and 2013 and as Vice President in 1999, 2005, 2009 and 2010; and Whereas, William J. Moran received a Trustee Award of Achievement from the Ohio Library Council for distinguished service and innovative leadership in October 2011 and served on the Ohio Library Council Board of Directors from Jan. 1, 2013 through Dec. 31, 2015; and Whereas, William J. Moran chaired two successful Library Levy campaigns in 2009 and 2013; and Whereas, As a Member of the Board of Trustees, William J. Moran works to help make the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County one of the largest, busiest, and best public libraries in the country, with tremendous growth over 20 years including increases of 49% in circulation and more than 50% in the number of cardholders; and Whereas, During his tenure on the Board, the Library received the 2013 National Medal for Museum & Library Service from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as well as three consecutive Five-Star ratings from Library Journal – one of only five libraries nationwide in the $30+ million expenditure category to receive this distinction; and Whereas, William J. -

Ohio Court of Appeals

DAILY COURT REPORTER A Newspaper of General Circulation within The Miami Valley Established 1917 Devoted to General, Political, Religious, Social, Business & Legal Events of the Day Vol.150-No. 5 Fax 419-470-8602 DAYTON, OHIO FRIDAY, JANUARY 31, 2020 (031 ) Phone 937-222-6000 1 dollar Periodicals 5 charged in $2.8 million Dark Web drug Postage Paid Toledo, OH trafficking, money laundering conspiracy In our editions... Court Calendars A federal grand jury has indicted Named in the indictment are: by the Department of Justice’s multi- Department of Homeland Security, Supreme Court of Ohio five individuals alleged to be members • Khlari Sirotkin, 36, of agency Special Operations Division Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms Court of Appeals of one of the most prolific online drug Colorado (SOD), including assigned attorneys and Explosives, Department of Justice Bankruptcies trafficking organizations in the United • Kelly Stephens, 32, of from the Narcotic and Dangerous Drug and Financial Crimes Enforcement Common Pleas Court New Suits, Judges Orders States. The indictment was returned Colorado Section. Network. Current Business and unsealed in Cincinnati. • Sean Deaver, 36, of Ne- This operation was facilitated The narcotics conspiracy in this Domestic Relations Court According to the 21-count in- vada in conjunction with the Joint Crimi- case is punishable by 10 years up to New Suits (Divorces) dictment, since 2013, co-conspirators • Abby Jones, 37, of Nevada nal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement life in prison. The money laundering Dissolutions of Marriage used several Dark Web marketplace • Sasha Sirotkin, 32, of Cali- (JCODE) team. JCODE is a FBI-led conspiracy is punishable by up to 20 Judges Orders accounts and encrypted messaging fornia. -

Shakeup at GE Lighting

20160208-NEWS--1-NAT-CCI-CL_-- 2/5/2016 3:45 PM Page 1 VOL. 37, NO. 6 FEBRUARY 8 - 14, 2016 MANUFACTURING: Outlook Business of Life It’s a mixed bag for industry in 2016 P. 6 Ice wine How frozen grapes SPORTS: Arena football become a sweet drink Cleveland is rare AFL success story P. 20-21 P. 8 The List FOCUS: Middle Market CLEVELAND BUSINESS Heinen’s downtown move paying off NEO’s largest software developers P. 15 P. 27 A to Z podcast making a mark BY KEVIN KLEPS frequent inquiries led to a partner- ship that really helped the podcast [email protected] take off. @KevinKleps Zac Jackson casually tells a re- Here to stay porter that he didn’t get an iPhone “I bugged them for a long time,” “until like a year ago.” said Grzegorek, the editor-in-chief of Andre Knott, his best friend and a pair of alternative weeklies, Cleve- podcast partner, immediately land Scene and the Detroit Metro chimes in, “And he still doesn’t know Times. how to use it.” Grzegorek said he would call Jack- The scene was a Panera’s in North son “at least once a month” and ask Olmsted, but it might as well have him if “it was time for us to have a se- been one of the undisclosed loca- rious conversation.” A display of tions (Jackson and Knott prefer to Late last summer, Scene made an LED technology keep their audience wondering) at offer — it would pay Jackson and at GE Lighting’s which the two record their increas- Knott a fee for the podcast, which ingly popular A to Z podcast. -

Political Contributions and Related Activity Report

Aetna PAC and Aetna Inc. Political contributions and related activity report 2008 AETNA PAC BOARD OF OFFICERS FEDERAL CONTRIBUTIONS COMMITTEE Last year, I joined Aetna as Senior Vice President, Government Affairs. One of the primary DIRECTORS - 2008 Steve Kelmar Charlie Iovino goals the Government Affairs team has this year is to educate legislators and the new Obama Mark Bertolini Chairman Vice President & Counsel, Administration about our company and the policy issues that affect our bottom line and ability President Senior Vice President, Government Affairs Federal Government Affairs to operate. We do this by meeting with Federal and State representatives and their staffs, through our employee-driven grassroots program, and through the Aetna Political Action Mary Claire Bonner Jonathan Topodas Steve Kelmar Committee—Aetna PAC. Segment Head, Regional Business Treasurer and Counsel Senior Vice President, Government Affairs Vice President & Counsel, Aetna PAC is a bipartisan political action committee, which allows eligible company employees William Casazza Federal Government Affairs Jonathan Topodas to have a voice with legislators on the Federal and State levels who make laws and policy that Senior Vice President, General Counsel Vice President & Counsel, have a direct impact on the way the company does business. Its purpose is to support candidates Tammy Preisner Federal Government Affairs for political office by collecting voluntary contributions from eligible Aetna employees. All Tom Kelly Assistant Treasurer & Administrator contributions are received and disbursed pursuant to our internal contribution guidelines Product Head, Schaller Anderson Manager, Government Affairs and in accordance with applicable election laws. STATE CONTRIBUTIONS COMMITTEE Steve Kelmar In January of 2008, Aetna’s Federal and State PACs started with a combined balance of Brooke Flaherty Senior Vice President, Government Affairs $307,685. -

We Tour Everywhere! NO FLYING! 2015 Vacations TROPICANA Motorcoach • Air • Cruise $25 Slot P.O

NEW TOURS! 72 with Volume 24 January-December 2015 SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS HOLIDAY CHRISTMAS ON THE RIVER WALK See page 62 for description See page 105 for description This holiday season, the Riverwalk shines brighter than Grand Canadian ever as thousands of colorful Christmas lights decorate Circle Tour the facades and reflects off the river in San Antonio. Visit the famed Alamo, decorated for the holiday season, enjoy the relaxed holiday atmosphere while See page 95 for description being guided along by more than 6,000 luminaries during Fiesta de las Luminaries, and take a riverboat ride and admire the many holiday decorations from the water! PANAMA CANAL CRUISE We Tour Everywhere! NO FLYING! TROPICANA 2015 Vacations $25 Slot Motorcoach • Air • Cruise Play P.O. Box 348 • Hanover, MD 21076-0348 410-761-3757 1-800-888-1228 www.gunthercharters.com Restroom 57/56/55 14 54/53 52/51 13 50/49 48/47 12 46/45 44/43 11 42/41 40/39 10 38/37 36/35 9 34/33 32/31 8 30/29 28/27 7 26/25 24/23 6 22/21 20/19 5 18/17 16/15 4 14/13 12/11 3 10/9 8/7 2 6/5 4/3 1 2/1 Row # Door Side Driver Side 2 2 INTRODUCTION PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION THOROUGHLY This section covers very important information and will answer many of your questions. Booking Your Tour Seating Information: 1. You must call to make your reservations, Monday 1. Passengers are assigned seats on all Gunther Tours. -

4K. Approve Letter of Support for National Register

Request for Council Action TO: Mayor and City Council THROUGH: Tim Murray, City Administrator FROM: Deanna Kuennen, Community and Economic Development Director MEETING DATE: March 23, 2021 SUBJECT: Approve Letter of Support for the National Register Nomination for Faribault Commercial Historic District Background: Attached is the City’s application to expand the National Register District for the Downtown Commercial Historic District. The Faribault HPC initiated this expansion several years ago to expand access to preservation incentives such as state and federal historic preservation tax credits, preservation easements and grant funds. If desired, the Mayor must transmit comments on the proposed nomination to the Minnesota Historical Society by April 2, 2021. The State Review Board will consider the nomination at their meeting on April 6, 2021. If approved by the State Review Board, the nomination would be placed on the Register approximately 60 days later. As required, the Faribault Heritage Preservation Commission held a public hearing to receive comments on the nomination at their meeting on March 15. No comments from the public were received. In addition, a public meeting was held with the State Historic Preservation Office, affected property owners, Hoisington Preservation Consultants and members of the public on January 25, 2021. Staff has received comments from affected property owners who were mostly neutral or supportive of the project. One property owner was concerned about how the expansion would affect their ability to demolish their structure(s). The HPC approved the attached letter of support and is sending it to the State Review Board for their consideration. Recommendation: Approve the attached letter of support for the application to expand the Faribault Commercial Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places and authorize the Mayor to sign the letter on their behalf. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPO R T O F THE LIBR ARIAN OF CONGRESS ANNUAL REPORT OF T HE L IBRARIAN OF CONGRESS For the Fiscal Year Ending September , Washington Library of Congress Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC For the Library of Congress on the World Wide Web visit: <www.loc.gov>. The annual report is published through the Public Affairs Office, Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -, and the Publishing Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -. Telephone () - (Public Affairs) or () - (Publishing). Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Copyediting: Publications Professionals LLC Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Design and Composition: Anne Theilgard, Kachergis Book Design Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen Library of Congress Catalog Card Number - - Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC - A Letter from the Librarian of Congress / vii Library of Congress Officers and Consultants / ix Organization Chart / x Library of Congress Committees / xiii Highlights of / Library of Congress Bicentennial / Bicentennial Chronology / Congressional Research Service / Copyright Office / Law Library of Congress / Library Services / National Digital Library Program / Office of the Librarian / A. Bicentennial / . Steering Committee / . Local Legacies / . Exhibitions / . Publications / . Symposia / . Concerts: I Hear America Singing / . Living Legends / . Commemorative Coins / . Commemorative Stamp: Second-Day Issue Sites / . Gifts to the Nation / . International Gifts to the Nation / v vi Contents B. Major Events at the Library / C. The Librarian’s Testimony / D. Advisory Bodies / E. Honors / F. Selected Acquisitions / G. Exhibitions / H. Online Collections and Exhibitions / I. -

OTT 2008 Brochure Final

2008 Tour Brochure 1 New Tours, Student / GranGrandparent,dparent, Religious, Out-of-State, Local Area and more tours!! Ohio Travel Treasures, LLC Member of NTA, ABA, OTA, Bank Travel, TP #88.87.0003 Where One Call Does It All 5270 Day Road * Cincinnati, Ohio 45252 * (513) 923-9112 or (800) 582-5997 * Fax (513) 923-3108 If you are looking for tours that IGNITE and EXCITE and Ohio Travel Treasures is a member of the National Tourism that are truly UNIQUE and DIFFERENT then don’t put Association, American Bus Association, Ohio Travel Asso- down this brochure. Every tour comes complete with ciation, Bank Travel and a multitude of other professional CUSTOMIZATION which means we never provide a associations and is licensed, bonded and insured. We are “COOKIE CUTTER,” tour! Our team specializes in finding your connection to a plethora of treasures that will meet unique and out-of-the-way attractions, dining venues and so your groups’ demands for different and unique. much more to create a memorable and lasting experience for you and your guests. The entire team looks forward to getting you started on your planning season, day trips, multi-night, extended...whatever Celebrating 15 years in the business, Ohio Travel Treasures your needs may be...if you can perceive it, we can achieve is your key to the most successful group tours. While we it!! If there is somewhere you would like to go and you could go on about a dozen other important features, the bot- don't see it in our brochure just give us a call and we will be tom line is that there’s only one really good reason to able to provide the specialist in that particular area. -

5B. Review National Register Nomination for Commercial Historic

Agenda Item: 58 ault Request for Action TO: Heritage Preservation Commission FROM: Kim Clausen, Community Development Coordinator MEETING DATE: February 22, 2021 SUBJECT: Review National Register Nomination for Faribault Commercial Historic District PURPOSE: The purpose of this item is to gather input on the Faribault Commercial Historic District National Register nomination and formulate an opinion for consideration by the State Review Board. DISCUSSION: Attached is the application expand the Faribault Commercial Historic District that is listed the National Register of Historic Places. The City is seeking this nomination in order to recognize the significance of the downtown historic district and increase access to State and Federal Historic Preservation Tax Credits and grant funds through the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. The HPC must allow an opportunity for public comment, and then prepare a report indicating its opinion as to whether the property meets the National Register Criteria. A public meeting was held with the State Historic Preservation Office, downtown property owners, Hoisington Preservation Consultants and members of the public on January 25, 2021. Staff has received comments from affected property owners who were mostly neutral or supportive of the project. One property owner was concerned about how the expansion would affect their ability to demolish their structure(s). In formulating the opinion, at least one Commission member who meets the Federal Standards for History and one Commission member who meets the Federal Standards for Historic Architecture or Architectural History (attached) should participate. If the HPC does not include a member who meets the Federal Standards, the HPC may obtain the opinion of a qualified professional in the subject area and consider the opinion in its recommendations. -

OGS FINDING AIDS 611 State Route 97 W Users of This Collection Should Credit the Ohio Genealogical Society in Any Reference Citing

OHIO GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OGS FINDING AIDS 611 State Route 97 W Users of this collection should credit the Ohio Genealogical Society in any reference citing. The OGS Archives is open to Bellville OH 44813-8813 the public Tuesday through Saturday from 9 AM to 5 PM. In- 419-886-1903 quiries may also be made using the OGS Copy Service (Library section of web site) where a Manuscript Key and OGS Finding www.ogs.org Aids may also be found. MSS #145 Title: Joseph H. Shaw Ohio History Collection Bulk Dates: 1956-1971 Inclusive Dates: 1956-1971 Description: 2 phase boxes consisting of 11 files Organization: BOX 1 File 1: Water Transportation in Ohio Upper Ohio Valley Association. Facts Versus Fantasy: The High Cost of Cheap Transportation. 1961. [Pamphlet about the proposed Ohio River-Lake Erie Canal.] Stark County Historical Society. St. Helena II of Canal Fulton. [Pamphlet with map and schedule for passenger boat trips on the St. Helena II on the Ohio-Erie Canal] Northwest Ohio Great Lakes Research Center. Bowling Green State University. [Brochure about the holdings of the Great Lakes Research Center.] The Great Lakes Historical Society, 1965. Vermilion, Ohio. [Pamphlet] The Great Lakes Historical Society, >1965. Vermilion, Ohio. [Pamphlet, updated] Steamboats on the Western Waters. Campus Martius Museum, Marietta, Ohio. [Brochure, including pictures of the Fram- ing of the W.P. Snyder, Jr. and the W.P. Snyder, Jr. on the river at Pittsburgh] Canal Society of Ohio, Inc. [Membership pamphlet] Upper Ohio Valley Association. Facts about the Proposed Lake Erie-Ohio River Canal. 1957. -

To Access the David Duniway Papers Finding Aide

Container List 1999.013 ~ Records ~ Duniway, David C. 07/19/2017 Container Folder Location Creator Date Title Description Subjects Box 01 1.01 1868-1980 Adolph-Gill Bldgs The materials in this folder relate to the buildings owned and occupied by J.K. Gill & Co. and by Sam Adolph. These two buildings are in the heart of the original business district of Salem. The Gill Building (1868) is west of the Adolph Block (1880), and they share a staircase. The Gill building was later referred to as the Paulus Building, as it was acquired by Christopher Paulus in 1885; both Robert and Fred Paulus were born upstairs in the building. The Adolph Building was erected by Sam Adolph following a fire that destroyed the wooden buildings on the site; the architect was J.S. Coulter. References to articles in the Daily American Unionist from April 23, 1868 through September 8, 1868 describe the four new brick buildings under construction on State and Commercial Streets. Thes buildings are the intended new homes for the businesses of J.K. Gill & Co., Charley Stewart, Durbin & Co., and Governor Wood's new dwelling. Progress is periodically described. Finally, the first ten days of September, 1868, the moves appear complete and advertisements indicate the items they will carry. Another article in the September 8, 1868 issue indicates that Story and Thompson are moving a house lately occupied by J.K. Gill and Co. to the eastern edge of the lot so that when it is time to construct additional brick buildings, there will be space. -

The Deal with Club Pilates Was Completed in a Professional“ Manner

www.REBusinessOnline.com May 2016 • Volume 14, Issue 9 The deal with Club Pilates was completed in a professional“ manner. The tenant’s lease comments and requests were fair, the tenant was very responsive during the negotiations; the business will be another first class addition to our center. Scott A Tucker ” CSM Vice President to Leasing (Chicago Region) KIMCO CLUB PILATES CONTACT: RICHARD FEINBERG – Vice President of Real Estate www.clubpilates.com/realestate CP AD 10.8125X14 COVER.indd 1 4/21/16 4:48 PM www.REBusinessOnline.com May 2016 • Volume 14, Issue 9 THE DISTRICT DETROIT AIMS NET LEASE TO BE GAME CHANGER FOR CITY INVESTMENT Bold mixed-use plan for area around arena fosters neighborhood concept. By Christina Cannon MAINTAINS ummer may be approaching, but workers on the Detroit BRISK PACE SEvents Center are cooling off as 1031 exchange buyers, the practice ice begins to take shape. With work on the roof and training fa- private investors drive cility underway, the new home of the demand, but cap rates NHL’s Red Wings is right on schedule to open for the 2017-2018 season. suggest cycle nears peak. With so much excitement surround- By Joe Gose ing the construction of the arena, it’s unger for yield and persistently easy to lose site of the other compo- low interest rates, the dynam- nents that will make up The District ics that have fueled a robust Detroit. In addition to the 20,000-seat H This building will be situated along Woodward Avenue and is part of The District net lease investment market for retail arena, 50 blocks between downtown Detroit’s Woodward Square neighborhood.