Copyright in Relation to This Thesis*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chenry Chronicles 8

Last Edition volume 1 number 8 August 2005 The Chenry Chronicle By Christopher and Heather Henry USS Blue Ridge Chris and the US Counsel General who is stationed in A model of the USS Blue Ridge. Sydney. Chris received an invitation in the mail from Kendo the US Counsel General and the Seventh Fleet Chris has taken up Kendo while here in to attend the reception on the USS Blue Ridge Toowoomba, Australia. Kendo is one of the ship. What an experience! It started at 6:30pm many arts of the Samurai, Kendo is the sport. in Brisbane near the sugar bulk dock. The ship Kendo is an old gentlemen’s, sport. There are had been on an exercise for three weeks with several related arts, but Kendo is a contact sport the Australian Navy. The ship just docked and where armor is worn and bamboo sticks are had a huge reception inviting many Australian used in the place of real swords. Chris dresses dignitaries and a few Americans. We were up in amour every week to give it a go. To the probably one of just a few Americans invited. untrained eye, it looks like a bunch of men There was a ceremony and the National trying to hit each other on the head with a stick, Anthem was played. It has been a long time but it is a very difficult sport to learn because since we have heard that song. The US of the many intricacies and traditions. They Counsel General and the Admiral cut the huge meet on Sunday morning and Monday sheet cake with a sword. -

2 PAST EVENTS ...3 Library NEWS ...7

wendish news WENDISHW HERITAGE SOCIETY A USTRALIA NUMBER 57 SEPTEMBER 2016 C ONTENTS Clockwise from top: CALENDAR OF UPCOMING EVENTS ........ 2 1. Tour Group members at the Nhill Lutheran Church (see page 3). PAST EVENTS ..................... 3 2. Albacutya homestead in the Wimmera – Mallee Pioneer Museum at Jeparit. LIBRARY NEWS ................... 7 3. Headstone of Helene Hampe (1840–1907), widow of Pastor G.D. Hampe, at Lochiel Lutheran TOURS ......................... 8 Cemetery. 4. Peter Gebert in his Kumbala Native Garden, near RESEARCH ...................... 9 Jeparit. 5. Daryl Deutscher, at the entrance to his Turkey Farm FROM OTHER SOCIETEIS JOURNALS ..... .10 with Glenys Wollermann, at Dadswell’s Bridge. 6. Chemist display at the Dimboola Courthouse REUNIONS ..................... .11 Museum. DIRECTORY ..................... .12 PHOTOS SUPPLIED BY CLAY KRUGER AND BETTY HUF Calendar of upcoming events 30th Anniversary Luncheon, Labour Day Weekend Tour to Saturday 15 October 2016 Portland, 11-13 March 2017 We will celebrate a special milestone this year: the Our tour leader, Betty Huf, has graciously offered to 30th Anniversary of our Society. You are warmly lead us on a tour of historic Portland on Victoria’s invited, along with family and friends, to attend this south-west coast, on 11-13 March 2017. Please note special Anniversary Luncheon to be held at 12 noon that this is the Labour Day long weekend in Victoria on Saturday 15 October in the Community Room and accommodation will need to be booked early at St Paul’s Lutheran Church, 711 Station St, Box due to the popularity of the Port Fairy Folk Festival. Hill, Victoria. (Please note that the luncheon venue The Henty family were the first Europeans to set- has been changed from the German Club Tivoli.) tle within the Port Phillip district (now known as The Church is near the corner of Whitehorse Rd Victoria), arriving at Portland Bay in 1834. -

The Telegraph and the Beginnings of Telemedicine in Australia

Global Telehealth 2012 67 A.C. Smith et al. (Eds.) © 2012 The authors and IOS Press. This article is published online with Open Access by IOS Press and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-152-6-67 The Telegraph and the Beginnings of Telemedicine in Australia Robert H EIKELBOOMa,b,1 a Ear Science Institute Australia, Subiaco, Australia b Ear Sciences Centre, School of Surgery, The University of Western Australia Abstract. The history of telemedicine is at times presented to commence in the 20th century. Events in Central Australia in 1874 show that the history goes further back, when the newly constructed telegraph played an important telemedicine role not only in enabling care for a wounded person, but also in uniting a dying man with his wife 2000 kilometres away. Innovation with the tools at hand has proven to be effective to bridge the tyranny of distance in the delivery of health care. Keywords. Telemedicine, history, Australia, telegraph Introduction Communication and information technologies are vital components in almost every telemedicine application, with advances in ICT usually driving development in telemedicine. The beginnings of telemedicine are to be found in the invention of the telegraph, with wireless, telephones, television, imaging devices, and the Internet all adding to the utility of telemedicine. Aronson [1] recounts the first reported use of the telephone for telemedicine in 1879 when a doctor listening to the cough of an infant reassured the grandmother that it was not croup and refused to attend for a house call. -

Grs 513/11/P

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRS 513 Lodged company documents of defunct companies Series These files contain documents lodged by companies in Description accordance with the varying Companies Acts. Company files may contain some or all of the following lodged documents: Memorandum of Agreement, Articles of Association, Certificate of Incorporation, lists of shareholders, lists of directors, special resolutions ie. issues of shares, underwriting agreements and annual returns. Note: The term 'defunct' should not be understood to refer to the company. In this context it refers to the file being defunct, although given the age of the records some of the companies will have become defunct. Series date range 1844 - 1986 Agency State Records of South Australia responsible Access Open. Determination Contents 1874 – 1935 1 June 2016 GRS 513/11/P DEFUNCT COMPANIES FILES 4/1S74 The Stonyfell Olive Company Limited (Scm) \ 4/1874 The Stonyfell Olive Co. Limited (1 file) 1/1875 The East End Market Company (16cm)) 1/1S75 The East End Market Coy. Ltd. (1 file) 3/1SSO The Executor Trust & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (9cm &9cm)(2 bundles)) 10/1S7S Adelaide Underwriters Association Limited (3cm) 10/1S7S Marine Underwriters Association of South Australia Limited (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder's Wool and Produce Company Limited (Scm) 4/1SS2 Northern Territory Laud Company Limited (4cm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia (Scm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (1 file) 7/1SS2 Northern Territory Land Company (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder Smith & Co. -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. 29 ISBN O 86740 357 8 ISSN 0816...,6323 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

Durham Downs — a Pastorale

This is part ofa set Braided Channels Vol 2 Item 4 and may NOT be borrowed separately. Durham Downs — a Pastorale The story of Australia told through the lives of two families, united in their passion for three million acres of land: Durham Downs. 070.18 FITZ [1-2] Concept document produced with the assistance of the Pacific Film and Television Commission and Film Australia. V-------- J > Up* i nfo@jerryca nfi I ms .corn au 32007004706179 PO Box 397 Nth Tambonne Braided channels : QLO 4272 documentary voice from an Ph *61 7 5545 3319 interdiscplinary, Fax +61 7 5545 3349 cross-media, and practitioners's perspective Synopsis Durham Downs - a Pastorale is a 1 x 52 minute documentary that explores the love of land and sense of place that this ancient landscape in far SW Queensland inspires through the story of two families. The film follows the lives of the Ferguson family, retiring managers of Durham Downs Station, as their home passes on to the next family of employees of S. Kidman and Co., the Station’s pastoral lease-holder. As they end a thirty year association with the property and an at least five generations association with the area, the Fergusons are grieving for the loss of their home and trying to make sense of who they will be without Durham Downs. Running in parallel to the Ferguson’s story is that of the Ebsworth family and the Wangkumarra people. Moved from their traditional home in the 1930s, and having worked for the Station over generations, oil and gas exploration of the land is creating new opportunities for them to relate to their land. -

Up in the Sky Year 3 - Unit Plan

LOOK! UP IN THE SKY YEAR 3 - UNIT PLAN > Living in Australia’s Outback Royal Flying Doctor Service Tasmania Building 90 Launceston Airport, 305 Evandale Road Western Junction TAS 7212 Prepared by Jocelyn McLean PO Box 140, Evandale TAS 7212 P: 03 6391 0512 E: [email protected] W: www.flyingdoctor4education.org.au RFDS Education Ocer LOOK UP INTO THE SKY > Living in Australia’s Outback Year 3 Australian Curriculum Humanities and Social Sciences Focus Topic of the unit Inquiry Questions Using the interactive resources located ‘www.flyingdoctor4education.org.au‘, > How do people contribute to their communities, past and present? students explore the development of the Royal Flying Doctor Service and the impact the organisation has on communities in the outback of > How has our community changed? Australia. They will investigate how the communities have changed over time and the role the Royal Flying Doctor Service has played in these > What is the nature of the contribution made by different groups and changes. Students will identify how the characteristics of a place shape individuals in the community? the industry, community and the lives of the people who live there. > What are the main natural and human features of Australia? Students Develop and Understanding of > How and why are places similar and different? > How the community has changed and remained the same over time and the role that the Royal Flying Doctor Service has played in the development and character of the local community (ACHASSK063) > The similarities and -

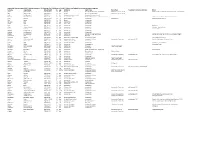

List of Deaths.Xlsx

Innamincka Records compiled 2011. Materials supplied b:- SA Genealogy Soc. D Spackman. K Buckley. Office for the Outback Community Authority, Pt Augusta. Surname Given Names Date of Death Sex Age Residence Death Place Burial Place Headstone Innamincka Cemetery Detail Burke Robert O'Hara 1861-06/07-? M 40y Victoria Near Burke Waterhole, Innamincka Melbourne General Cem Memorial Burke's Waterhole Cooper Creek Nr Innamincka Wills William John 1861-06/07-? M 27y Victoria Near Tilcha Waterhole Melbourne General Cem Colless Not Recorded 1880-08-17 F 3h Innamincka Coopers Creek Innamincka Coopers Creek Howard Henry Grenville 1881-11-01 M 50y Innamincka Station Between Mt Lyndhurst and Farina Town Cook. Injuries received thrown from his trap. Cook Richard 1883/4-12-02 M 45y Monta Collina Innamincka Patchewarra Police Mortuary Returns Tee James 1885-05-13 M 37y Farina Innamincka Richards John 1886-02-08 M 61y Innamincka Innamincka Budge John 1887-03-22 M 23y Oonta. Qld Innamincka Dick Samuel 1887-09-07 M 3w Innamincka Innamincka Bronchitis Rowe Thomas Roberts 1888-03-22 M 20y Innamincka Innamincka Labourer. Typhoid Fever. Copp Andrew 1888-05-10 M 37y Innamincka Innamincka Cancer of Throat Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 36h Innamincka Innamincka Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 24h Innamincka Innamincka Charley Not Recorded 1893-11-15 M 23y Innamincka Coopers Crk near Lake Hope Aboriginal. Drover.Verdict of Jury -no cause of death McDermott John 1891-07-12 M 36y Innamincka Adelaide Crossman William 1891-08-20 M 30y Nappa Merrie Station Qld Innamincka Station Police Mortuary Returns Bralla William Emanuel 1894-01-23 M 23y Innamincka Station Innamincka Station Innamincka Cemetery photograph 2011 Accidentally drowned Coopers Creek Hampton Edwin John 1894-12-28 M 23y Asbevale Station Qld Innamincka Smith Alick 1895-03-30 M 53y Innamincka Station Innamincka Stockman. -

External Link Teacher Pack

Episode 14 Questions for discussion 29th May 2018 Live Export Debate 1. Discuss the Live Export Debate story with another student. Share your thoughts with the class. 2. What are live exports? 3. How much money do Australian producers make from live exports every year? 4. Why do some countries prefer to buy live Australian animals? Give one example. 5. Some video footage of animals on their way to the Middle East has recently emerged. How did the vision make some people feel? 6. The Government will be making some changes to the live exports industry. Give one example. 7. Which country has shut down their live export industry? 8. What are some of the pros and cons for shutting down Australia’s live export industry? 9. What do you think? Should live exports be banned? Explain your answer. 10. How did this story make you feel? Write a message about the story and post it in the comments section on the story page. What is a treaty? 1. Summarise the What is a treaty? story, using your own words. 2. What is a treaty? 3. A treaty is a legal agreement. True or false? 4. When New Zealand became a colony, Indigenous people weren’t given any rights. True or false? 5. When the British first arrived in Australia it was claimed Terra Nullius. What does this mean? 6. Complete this sentence. Many people in Australia say a treaty would be a huge step towards _____________ between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous people. 7. What was the ‘Barunga Statement’? 8. -

Indexes to Correspondence Relating to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the Records

Indexes to correspondence relating to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the records of the Colonial Secretary’s Office and the Home Secretary’s Office 1896 – 1903. Queensland State Archives Item ID 6820 88/4149 (this top letter is missing) Letter number: 88/328 Microfilm Z1604, Microfilm frame numbers 3-4 contain a copy of the original letter. The original is contained on frames 5-6. Letter from the Reverend GJ Richner on behalf of the Committee for the Lutheran Mission of South Australia. He acknowledges receipt of the Colonial Secretary's letter advising that CA Meyer and FG Pfalser have been appointed trustees of Bloomfield River Mission Station (Wujal Wujal). He also asks for government support for both Bloomfield River and Cape Bedford Mission stations. He suggests that "It is really too much for the Mission Societies to spend the collections of poor Christians for to feed the natives". A note on letter 88/328 advises "10 pounds per month for 12 months". Queensland State Archives Item ID 6820 88/4149 (this top letter is missing) Letter number: 88/4058 Microfilm Z1604, Microfilm frame numbers 8-9 contain a copy of the original letter. (The original is contained on frames 10-11). Letter from the Reverend GJ Richner thanking the Colonial Secretary for the allowance of 10 pounds per month for Cape Bedford and Bloomfield River Mission Stations. He suggests, however, that the 10 pounds is "fully required" for the Cape Bedford Mission Station and asks for further funding to support Bloomfield River Mission Station. Queensland State Archives Item ID 6820 88/9301 (this top letter is missing) Letter number: 87/7064 Microfilm Z1604, Microfilm frame numbers 14-15. -

29 April 2020 Santos Reference: CB20-05 Ms Dominique Taylor

29 April 2020 Santos Reference: CB20-05 Ms Dominique Taylor Team Leader, Energy, Extractive and South West QLD Compliance (Assessment) Department of Environment and Science Level 7, 400 George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Dominique, Application to Amend Environmental Authority EPPG00407213 (Petroleum Lease (PL) 80) Santos Ltd (Santos) on behalf of its joint venture partners has prepared the attached application to amend Environmental Authority (EA) EPPG00407213. The application has been prepared in accordance with Sections 226 and 227 of the Environmental Protection Act 1994 (EP Act). This application seeks a change to the scale and intensity for the activities authorised by the EA through the amendment of conditions A1 - A3. The following information is attached in support of the amendment application: • Attachment 1 – EA Amendment Application Form • Attachment 2 – Supporting Information The amendment application has been prepared as a major amendment. The application fee of $334.90 has been paid upon lodgement of the application. Please contact me on 3838 5696 or [email protected] should you have any questions in relation to the application. Yours sincerely, Elizabeth Dunlop Santos Limited Attachment 1 – EA Amendment Application Form Attachment 2 – Supporting Information Attachment 2 – Supporting Information for an Environmental Authority (EA) Amendment Application Petroleum Lease (PL) 80 EA EPPG00407213 Table of Contents: 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. -

Powering Community Development CLP.CONNECT #009 SEP, 2019

CLP.CONNECT #009 SEP, 2019 Powering Community Development CLP.CONNECT #009 SEP, 2019 Powering Community Development Dear colleagues, It’s been an unsettling summer and a testing time for Hong Kong. It is also very disheartening to see what is going on. Having adopted Hong Kong as my home and lived here for more than 25 years I know what a special place this is. As a parent it’s heartbreaking to see the despair in our city’s young people. But I believe the people of Hong Kong have a strong resilience and I hope the city’s Lion Rock Spirit can pull everyone together through this difficult period. Over more than a century CLP has grown with Hong Kong through thick and thin. We are a proud member of this community and care deeply about our home. That’s why we have made “Caring for the Community” one of CLP’s core values and put a spotlight on our community initiatives in this issue of CLP.CONNECT. The Kadoorie family have been Asia’s philanthropic leaders for generations. Their value has not only helped millions of people, but also inspired CLP to contribute to the communities in which we live and work. The cover story takes you back to the 19th century to look at how the Kadoorie family’s charitable tradition touched many lives in old Hong Kong. This year marks the 25th anniversary of our CLP Volunteer Team in Hong Kong. What started out as a frontline staff-initiated volunteer ▲The CLP Volunteer Team has been serving Hong group providing free rewiring services to underprivileged elderly Kong for 25 years.