Impact Assessment Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chenry Chronicles 8

Last Edition volume 1 number 8 August 2005 The Chenry Chronicle By Christopher and Heather Henry USS Blue Ridge Chris and the US Counsel General who is stationed in A model of the USS Blue Ridge. Sydney. Chris received an invitation in the mail from Kendo the US Counsel General and the Seventh Fleet Chris has taken up Kendo while here in to attend the reception on the USS Blue Ridge Toowoomba, Australia. Kendo is one of the ship. What an experience! It started at 6:30pm many arts of the Samurai, Kendo is the sport. in Brisbane near the sugar bulk dock. The ship Kendo is an old gentlemen’s, sport. There are had been on an exercise for three weeks with several related arts, but Kendo is a contact sport the Australian Navy. The ship just docked and where armor is worn and bamboo sticks are had a huge reception inviting many Australian used in the place of real swords. Chris dresses dignitaries and a few Americans. We were up in amour every week to give it a go. To the probably one of just a few Americans invited. untrained eye, it looks like a bunch of men There was a ceremony and the National trying to hit each other on the head with a stick, Anthem was played. It has been a long time but it is a very difficult sport to learn because since we have heard that song. The US of the many intricacies and traditions. They Counsel General and the Admiral cut the huge meet on Sunday morning and Monday sheet cake with a sword. -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. 29 ISBN O 86740 357 8 ISSN 0816...,6323 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

Powering Community Development CLP.CONNECT #009 SEP, 2019

CLP.CONNECT #009 SEP, 2019 Powering Community Development CLP.CONNECT #009 SEP, 2019 Powering Community Development Dear colleagues, It’s been an unsettling summer and a testing time for Hong Kong. It is also very disheartening to see what is going on. Having adopted Hong Kong as my home and lived here for more than 25 years I know what a special place this is. As a parent it’s heartbreaking to see the despair in our city’s young people. But I believe the people of Hong Kong have a strong resilience and I hope the city’s Lion Rock Spirit can pull everyone together through this difficult period. Over more than a century CLP has grown with Hong Kong through thick and thin. We are a proud member of this community and care deeply about our home. That’s why we have made “Caring for the Community” one of CLP’s core values and put a spotlight on our community initiatives in this issue of CLP.CONNECT. The Kadoorie family have been Asia’s philanthropic leaders for generations. Their value has not only helped millions of people, but also inspired CLP to contribute to the communities in which we live and work. The cover story takes you back to the 19th century to look at how the Kadoorie family’s charitable tradition touched many lives in old Hong Kong. This year marks the 25th anniversary of our CLP Volunteer Team in Hong Kong. What started out as a frontline staff-initiated volunteer ▲The CLP Volunteer Team has been serving Hong group providing free rewiring services to underprivileged elderly Kong for 25 years. -

Aboriginal Australian Cowboys and the Art of Appropriation Darren Jorgensen

Aboriginal Australian Cowboys and the Art of Appropriation Darren Jorgensen IN AMERICA, THE IMAGE OF THE COWBOY configures the ideals of courage, freedom, equality, and individualism.1 As close readers of the genre of the Western have argued, the cowboy fulfills a mythical role in American popular culture, as he stands between the so-called settlement of the country and its wilderness, between an idea of civilization and the depiction of savage Indians. The Western vaulted the cowboy to iconic status, as stage shows, novels, and films encoded his virtues in narratives set on the North American frontier of the nineteenth century. He became a figure of the popular national imagination just after this frontier had been conquered.2 From the beginning, the fictional cowboy was a character who played upon the nation’s idea of itself and its history. He came to assume the status of national myth and informed America’s economic, political, and social landscape over the course of the twentieth century.3 Yet this is only one na- tion’s history of the cowboy. As America became one of the largest exporters of culture on the planet, it exported its Western imagery, genre films, and novels. These cowboys were trans- formed in the hands of other cultural producers in other countries. From East German Indi- anerfilme to Italian spaghetti Westerns and Mexican films about caudillos (military leaders), the Darren Jorgensen is an associate professor in the School of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia. He researches and publishes in the area of Australian art, as well as on contemporary art, critical theory, and science fiction. -

Kleberg .. King Ranch Add up to Nearly 1 0 Millio1 of Cattle Land

Kleberg .. King Ranch • . Runl add up to nearly 10 millio1 of cattle land across our Wben historians even amass. As a pastoral spe abroad. But the black gold 51 (member of a long estab Sir Rupert is corporation Two properties, Elgin tually sit down to compile cialist Kleberg has few was risked and is helping to lished land family with large chairman today and the Downs and New Twin Hill! their list of greats for the peers, and is certainly the burn the Running W into holdings in Queensland and company has been made se were available on Ion~ 20th century, the name of most professional in the tens of thousands of cattle _the Northern Territory). nior holding group for all leaseholds from the Queens· Texas cattle baron Robert fields of range grasses, across the world. They were the aristocrats Australian operations. Capi land Government which Justus Kleberg Jr. undoubt horse and cattle genetics But before the fusing of of the country's pastoralists tal outlays so far are ac gave Kleberg a further as edly will be among them. and cattle pharmacopoeia, hot iron and beef flesh, - men Australians would knowledged to be about $15 surance that huge tracts of As reigning head of the outside universities and gov came his quest for land. It know, and through whom million. adjacent land would be family kingdom of King ernment bureaus. began in the early 1950s and they would come to know Sir Samuel Hordern died available at modest rates it Ranch Incorporated. Kle Applying this knowledge the three areas chosen to put King Ranch and what it in a car smash nine years he and I.P.L. -

98 KIMBERLEY I Have Only Once Kept a Diary in My Life and That Was

KIMBERLEY I have only once kept a diary in my life and that was during my time in Kimberley, and the extraordinary thing is that over the 50 years that have passed since that time it has remained in my possession. Keeping the diary on this one occasion was probably something to do with the stories Hedley had told me from Archibald Watson’s diaries only months before I went north. Sadly my diary makes very dull reading compared to those tales, but when I read it recently it did make my Kimberley days come alive for me again. The diary also played a part in my life many years later when I became interested in the Bradshaw paintings of Kimberley. My entries capture my reaction to meeting Aborigines for the first time and working with black people. It was not until WWII when the American army was billeted in England that most Britishers came in contact with black people. My first mass contact with a coloured race had been with the Zulu stevedores in Cape Town, when the ship had docked to load cargo on my voyage from England to Australia. The diary shows how my feelings about the Aborigines changed from fear to a paternal friendship. I read that I arrived in Perth on April 6th 1955 and stayed at the old Esplanade Hotel. What a superb old-fashioned Victorian hotel it was in those days! I am sure it has long since been pulled down; if so, what a shame! I was only in Perth long enough to meet the owner of Liveringa Station, Mr Forest, who I hoped would employ me. -

YUGUL an Arnhem Land Cattle Station V

G fpHD9433.A84Y84 ■ .T55 YUGUL Meven lhiele An Arnhem Land Cattle Station i \ N I \ N u m b i| Besw ick K a th |n i jlfe ry e i'. „ \ yl » u■■D^'t'cr i p i f f l f / B a r 1 1 I 1 The Australian National University North Australia Research Unit HD9433 A84Y84 T55 «-N.U. LIBRARY V This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. Steven Thiele YUGUL An Arnhem Land Cattle Station The Australian National University North Australia Research Unit Monograph Darwin 1982 First published in Australia 1982 Printed in Australia by the Australian National University (c) Steven Thiele, 1982. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher - North Australia Research Unit, PO Box 39448, Winnellie, N.T., 5798, Australia. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Thiele, Steven. Yugul, an Arnhem Land cattle station. Bibliography. ISBN 0 86784 007 2. ISSN 0 728-9499 1. Yugul Cattle Company. 2. Cattle trade - Northern Territory - Arnhem Land. I. Australian National University. North Australia Research Unit. II. Title. (Series : Monograph (Australian National University. -

A Geography of Water Matters in the Ord Catchment, Northern Australia

A Geography of Water Matters in the Ord Catchment, Northern Australia Jessica Emma McLean A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geosciences University of Sydney 2010 Abstract This thesis examines water matters in the Ord catchment. It shows how social, environmental, cultural and economic dynamics are manifest in water matters. In so doing, it critiques material and discursive practices that create environmental injustices, and highlights efforts underway to remedy those. The thesis makes two major contributions. First, to dissect water politics in the Ord through the prism of how water matters – from water supply and sanitation, to water allocations for cultural flows. Second, to demonstrate a theoretical means towards this end, by combining political ecology and environmental justice with a Masseyian spatial approach. Water, as a physical substance, makes tangible invisible power relations. To consider this, the thesis marries political ecology, with its focus on how power and politics help shape human-environment relationships, to environmental justice. A politics of difference informs the particular type of environmental justice drawn on here: it asks whether there is recognition of difference, plurality of participation, and equity in distribution of benefits, in environmental matters (Schlosberg, 2004). This nuanced theoretical terrain blends well with a Masseyian spatial approach that acknowledges places as made of ʻloose ends and missing linksʼ (Massey, 2005:12). The latter holds that places are never finished, are always being made, while the former analyses how power relations operate throughout processes. The thesis presents water matters as contested yet crucial to making sense of social- environmental relations; through contextualizing governance transformations and current water dilemmas, the shape of this contestation becomes clear. -

Past, Present and Future in Gina Rinehart's Land Plan

Past, present and future in Gina Rinehart’s land plan Terry McCrann, Herald Sun October 10, 2016 AUSTRALIA’S richest woman Gina Rinehart has brought together two of the greatest names in the nation’s history and in its development. She has very neatly unified past, present and future. In spending around a quarter of a billion dollars to buy control of a slice of Australia, big enough to actually be seen with the naked eye from the moon, she’s also got Treasurer Scott Morrison out of a rather uncomfortable position. More importantly, Rinehart’s deal provides Morrison with something of a template for handling a critical part of what is going to be our most dominant, most challenging and most complex relationship with any country over the next half-century at least. If only we had ‘half-a-dozen Rineharts’, able and prepared to do the same thing. Obviously, we don’t: we’ll need to promote ‘synthetic Rineharts’ to do what she’s done, from among the ranks of mainstream institutional investors instead. On Sunday, Rinehart’s central company Hancock Prospecting announced the $365 million purchase of the S Kidman & Co pastoral group, which has an average carrying capacity of 185,000 cattle over 101,000sq km of leases stretching across three states (Queensland, South and Western Australia) and the Territory. That’s an area equal to about 1½ Tasmanias, or around 40 per cent of Victoria. Rinehart’s Hancock will own two-thirds of and control the corporate buying vehicle, the other one-third will be owned by a Chinese partner — splitting the cost roughly $243 million/$122 million. -

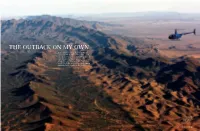

The Outback on My Own

THE OUTBACK ON MY OWN In the 80 percent of Australia that’s basically the middle of nowhere, you’ll face 10,000-year-old history—and your own grit. During three weeks adventuring in the Northern Territory, South Australia and Queensland, CHLOE SACHDEV finds a salve in the solitude. The easy way into Arkaba Conservancy, in South Australia’s COURTESY OF ARKABA OF COURTESY backcountry. TRAVELANDLEISUREASIA.COM 67 giant tapestry, distances are far, creatures are fierce and the climate can be brutal, but the reward is the sheer thunderclap beauty that feels otherworldly, almost extra-terrestrial. Nothing prepares you for this place. And doing it alone is equal parts terrifying and empowering. Over three weeks I’m trekking lush mountains and deep valleys, discovering the burnt-red gorges of the Kimberleys that are as deep as skyscrapers are tall, a terracotta desert bigger than most countries, and a sky that glows like an ember at sunset. But more than seeing anything in particular, I want to experience the feeling of being swallowed by the vastly different landscapes of South Australia, the Northern Territory and Far North Queensland. I finally reach Arkaba Conservancy, a 24,200-hectare isolated wildlife preserve hidden in the folds of the Flinders Rangers of South Australia, and framed by the magnificent crater-like formation of Wilpena Pound, so deep it can stack multiple Ulurus. Its curves and contours hold ancient I’ve been driving for two seabeds and the cavernous valleys are covered in forests of native pines and river red gums. I arrive hours before the dust hits. -

Cooksland in North-Eastern Australia

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

ATE17 Farmstays and Agritourism In

FARMSTAYS AND AGRITOURISM IN NSW Farmstays are a great way to get to know what country life is like in Australia. Farmstays in NSW offer a wide variety of activities for visitors including the chance to crack a whip, watch sheepdogs in action, shear a sheep and enjoy traditional Aussie damper by the campfire. Multi-region Australian Farm Tourism Australian Farm Tourism (AFT) is a division of Banora International Group, an inbound company providing expertise in the education, student, technical visit and homestay markets. AFT coordinates FIT and group host farmstays and technical visits in 13 locations Australia-wide. Locations in NSW include Bathurst, Central Coast, Hawkesbury, Holbrook and Tweed Valley. Tel: +61 7 4041 7990 www.austfarmtourism.com Horse riding, Scone Australian Wildlife, Farmstay and Remote National Parks Tour – AEA Luxury Tours Diamond Series This two-day, one-night private charter tour includes accommodation at a working sheep and cattle station, wine tasting in the Hunter Valley and the stunning scenery of Coolah Tops, Wollemi and Blue Mountains national parks. Tel: +61 2 9971 2402 www.aealuxury.com.au Quadrant Australia Operating for over 30 years across Australia, Quadrant specialises in tailor- made, special interest programs including agricultural technical tours, trade Wine tasting missions and nature-based programs showcasing wildflowers, birdwatching Image courtesy of AEA Luxury Tours and natural history. Tel: +61 2 6772 9066 www.quadrantaustralia.com Cattle dog, Moree Current as at 1 April 2017 Near Sydney AAT Kings - Aussie Farm, Food & Wine Trail This unique full-day tour is exclusive to AAT Kings. Guests can escape the city and experience the Australian bush, whilst visiting a fruit orchard and Tobruk, an authentic farmstay, only 70-minutes’ drive from Sydney.