Brief Amici Curiae of Players Associations of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amicus Brief

Nos. 20-512 & 20-520 In The Supreme Court of the United States ----------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION, Petitioner, v. SHAWNE ALSTON, ET AL., Respondents. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE, ET AL., Petitioners, v. SHAWNE ALSTON, ET AL. Respondents. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- On Writs Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit ----------------------------------------------------------------------- BRIEF OF GEORGIA, ALABAMA, ARKANSAS, MISSISSIPPI, MONTANA, NORTH DAKOTA, SOUTH CAROLINA, AND SOUTH DAKOTA AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS ----------------------------------------------------------------------- CHRISTOPHER M. CARR Attorney General of Georgia ANDREW A. PINSON Solicitor General Counsel of Record ROSS W. B ERGETHON Deputy Solicitor General DREW F. W ALDBESER Assistant Solicitor General MILES C. SKEDSVOLD ZACK W. L INDSEY Assistant Attorneys General OFFICE OF THE GEORGIA ATTORNEY GENERAL 40 Capitol Square, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30334 (404) 458-3409 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents ................................................. i Table of Authorities ............................................. ii Interests of Amici Curiae .................................... 1 Summary of the Argument .................................. 3 Argument ............................................................ -

Jeffery Picked by Minnesota in WNBA Draft 2Nd Round - Cubuffs.Com - Official Athletics Web Site of the University of Colorado

4/16/13 Jeffery Picked By Minnesota In WNBA Draft 2nd Round - CUBuffs.com - Official Athletics Web site of the University of Colorado Chucky Jeffery is the only player in school history with 1,600 points, 900 rebounds and 400 assists Photo Courtesy: Joel Broida Jeffery Picked By Minnesota In WNBA Draft 2nd Round Release: 04/15/2013 Courtesy: Troy Andre, Assistant SID BOULDER – University of Colorado senior Chucky Jeffery was selected by the Minnesota Lynx in the second round of the Watch: 2013 WNBA draft Monday. Chucky Jeffery 2013 WNBA Draft 04/16/2013 She was the 12th pick in the second round and the 24th pick overall. Chucky Jeffery Bio Sheet “I’m truly excited to be a part of the Minnesota Lynx organization,” Jeffery said. “I can’t wait to meet everyone. I’ve always loved Seimone (Agustus); watching Maya Moore, and coming in with (first round pick and Nebraska point guard) Lindsey Moore, it’s going to be fun. “I’m looking forward to learning everything from the veterans and elevate my game.” Minnesota was the 2011 WNBA champion and runner up in 2012, finishing 27-7 and first in the Western Conference. The Lynx are coached by Cheryl Reeve. Jeffery watched the draft on a snowy Colorado night with her Colorado teammates. Once she saw her name on the screen, she caught herself just staring at the television, while her fellow Buffaloes celebrated around her. www.cubuffs.com/ViewArticle.dbml?PRINTABLE_PAGE=YES&ATCLID=207234860&DB_OEM_ID=600 1/3 4/16/13 Jeffery Picked By Minnesota In WNBA Draft 2nd Round - CUBuffs.com - Official Athletics Web site of the University of Colorado “My teammates were going crazy, I had already been a little nervous; it was getting rough,” Jeffery said. -

The Astros' Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal Major League Baseball (MLB) fosters an extremely competitive environment. Tens of millions of dollars in salary (and endorsements) can hang in the balance, depending on whether a player performs well or poorly. Likewise, hundreds of millions of dollars of value are at stake for the owners as teams vie for World Series glory. Plus, fans, players and owners just want their team to win. And everyone hates to lose! It is no surprise, then, that the history of big-time baseball is dotted with cheating scandals ranging from the Black Sox scandal of 1919 (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”), to Gaylord Perry’s spitter, to the corked bats of Albert Belle and Sammy Sosa, to the widespread use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, the Houston Astros have joined this inglorious list. Catchers signal to pitchers which type of pitch to throw, typically by holding down a certain number of fingers on their non-gloved hand between their legs as they crouch behind the plate. It is typically not as simple as just one finger for a fastball and two for a curve, but not a lot more complicated than that. In September 2016, an Astros intern named Derek Vigoa gave a PowerPoint presentation to general manager Jeff Luhnow that featured an Excel-based application that was programmed with an algorithm. The algorithm was designed to (and could) decode the pitching signs that opposing teams’ catchers flashed to their pitchers. The Astros called it “Codebreaker.” One Astros employee referred to the sign- stealing system that evolved as the “dark arts.”1 MLB rules allowed a runner standing on second base to steal signs and relay them to the batter, but the MLB rules strictly forbade using electronic means to decipher signs. -

Dr. Lewis Yocum J U L Y 2 0 1 3

PBATS.COM S P E C I A L P O I N T S O F TALES OF THE TAPE INTEREST: DR. LEWIS YOCUM J U L Y 2 0 1 3 DR. LEWIS YOCUM— LOS ANGLES ANGELS OF DR. LEWIS YOCUM ANAHEIM DR. LEWIS YOCUM— “He was a dear friend and mentor. We both FAMILY and started together in 1978 and had been together for 36 FRIENDS years. One of our best moments was the 2002 World th DR. LEWIS Championship during our 25 year together. YOCUM— PBATS PRES- Dr. Yocum was a family man, humble, a gentleman, IDENTS witty, had a dry sense of humor, dedicated, honest, sin- DR. LEWIS cere, grateful and always looked after the best interests YOCUM— of his patients no matter who they were. PBATS HALL OF FAME We were both “foodies” and loved chasing great restau- rants, food, cigars. When we had dinner together (and we had many) we almost always talked about our fami- lies, friends, food, and our travels. INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Dr. Yocum always had time for everyone from the owner of the team, a summer intern, a bat boy, or another physician. ADAM NEVALA 2 DON YOCUM 3 He was a brilliant surgeon but almost always preferred to take the con- servative route with therapy, prehab, rehab, and exercise programs. SUE O’DRISCOLL 3 He was the best teacher I ever had and was always willing to share his PAST PBATS PRESI- 4-6 DENTS knowledge, wisdom, and expertise. RICHIE BANCELLS 5 He was always very proud of the educational values and opportunities that PBATS made available and also what PBATS stood for. -

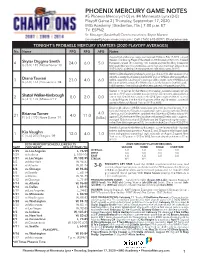

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) Vs

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) vs. #4 Minnesota Lynx (0-0) Playoff Game 2 | Thursday, September 17, 2020 IMG Academy | Bradenton, Fla. | 7:00 p.m. ET TV: ESPN2 Sr. Manager, Basketball Communications: Bryce Marsee [email protected] | Cell: (765) 618-0897 | @brycemarsee TONIGHT'S PROBABLE MERCURY STARTERS (2020 PLAYOFF AVERAGES) No. Name PPG RPG APG Notes Aquired by the Mercury in a sign-and-trade with Dallas on Feb. 12, 2020...named Western Conference Player of the Week on 9/8 for week of 8/31-9/6...finished 4 Skylar Diggins-Smith 24.0 6.0 5.0 the season ranked 7th in scoring, 10th in assists and tied for 4th in three-point G | 5-9 | 145 | Notre Dame '13 field goals (46)...scored a postseason career-high and team-high 24 points on 9/15 vs. WAS...picked up her first playoffs win over Washington on 9/15 WNBA's all-time leader in postseason scoring and ranks 3rd in all-time assists in the playoffs...6 assists shy of passing Sue Bird for 2nd on WNBA's all-time playoffs as- 3 Diana Taurasi 23.0 4.0 6.0 sists list...ranked 5th in the league in scoring and 8th in assists...led the WNBA in 3-pt G | 6-0 | 163 | Connecticut '04 field goals (61) this season, the 11th time she's led the league in 3-pt field goals... holds a perfect 7-0 record in single elimination games in the playoffs since 2016 Started in 10 games for the Mercury this season..scored a career-high 24 points on 9/11 against Seattle in a career-high 35 mimutes...also posted a 2 Shatori Walker-Kimbrough 8.0 2.0 0.0 career-high 5 steals this season in the 8/14 game against Atlanta...scored G | 6-1 | 170 | Missouri '19 in double figures 5 of the final 8 games of the regular season...scored 8 points in Mercury's Round 1 win on 9/15 vs. -

Seattle Storm Select Cedar Hill High School Graduate Joyner Holmes in 2020 Wnba Draft

Michael Sudhalter Communications Coordinator [email protected] 281-979-8109 For Immediate Release April 17, 2020 SEATTLE STORM SELECT CEDAR HILL HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATE JOYNER HOLMES IN 2020 WNBA DRAFT (CEDAR HILL, TX) - Joyner Holmes is one of the best athletes in the storied history of Cedar Hill ISD. As a high school senior in 2016, she was the top girls basketball recruit in the United States and became the first female CHISD Scholar to be selected to two prestigious games – the McDonald’s All-American Game in Chicago and the Jordan Brand Classic in New York City. Holmes, now a 22-year University of Texas senior, made history once again on Friday night when the Seattle Storm drafted her in the second round (19th overall) of the 2020 WNBA Draft. She became the first CHISD athlete to be selected in the WNBA Draft, and Seattle is just two years removed from a WNBA Championship. Only 10 UT Women’s Basketball Players have been drafted by the WNBA, since the League started in 1997. Holmes became the sixth former UT player to be drafted in the Top 20. Longhorn fans -- both CHISD and UT -- will be able to see Holmes play when the Storm visits its Western Conference rival, the Dallas Wings, who play their home games at the College Park Center in Arlington. The COVID-19 Crisis has altered plans globally, and the sports world is no different. On March 13, Holmes – a 6-foot-3 forward and her UT teammates were planning on facing West Virginia in the first round of the Big 12 Conference Tournament in Kansas City, Missouri. -

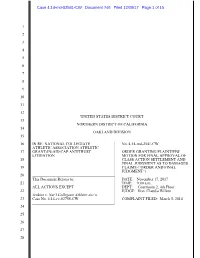

Order Granting Final Approval

Case 4:14-md-02541-CW Document 746 Filed 12/06/17 Page 1 of 15 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 13 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 14 OAKLAND DIVISION 15 16 IN RE: NATIONAL COLLEGIATE No. 4:14-md-2541-CW ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION ATHLETIC 17 GRANT-IN-AID CAP ANTITRUST ORDER GRANTING PLAINTIFFS’ LITIGATION MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF 18 CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND FINAL JUDGMENT AS TO DAMAGES 19 CLAIMS (“ORDER AND FINAL JUDGMENT”) 20 This Document Relates to: DATE: November 17, 2017 21 TIME: 9:00 a.m. ALL ACTIONS EXCEPT DEPT: Courtroom 2, 4th Floor 22 JUDGE: Hon. Claudia Wilken Jenkins v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n 23 Case No. 4:14-cv-02758-CW COMPLAINT FILED: March 5, 2014 24 25 26 27 28 Case 4:14-md-02541-CW Document 746 Filed 12/06/17 Page 2 of 15 1 2 I. BACKGROUND 3 Plaintiffs seek final approval of a settlement that provides for payment of approximately 50% 4 of the classes’ single damages claims after fees and expenses are deducted. The settlement agreement 5 is the result of extensive litigation and arm’s-length negotiations between the parties. Defendants 6 agree to pay $208,664,445.00, which (after deduction of fees and expenses) will be disbursed to 7 student-athletes who attended Division I schools that plaintiffs’ evidence shows would have awarded 8 the full cost of attendance at those schools (“COA”), but for the NCAA bylaw in effect until January 9 1, 2015, that capped the maximum grant-in-aid (“GIA”) at less than COA. -

Summary Letter to the American Re COVID Title IX Aresco 6 5 2020

June 5, 2020 Commissioner Michael Aresco American Athletic Conference 15 Park Row West 3rd Floor Providence, RI 02903 Dear Commissioner Aresco, We are a consortium of advocates for women and girls in sports. Access to and participation in sports improves the lives of all students, and that is particularly true for girls and women. During this time of COVID-19, we are writing to remind you of your institutional obligation to uphold Title IX.1 We understand that these are trying times for collegiate institutions, including athletics departments. In response to financial pressures, we have become aware that some universities are considering program cuts to their athletic programs.2 As the commissioner of the 1 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1688. 2 Sallee, Barrett. “Group of Five Commissioners Ask NCAA to Relax Rules That Could Allow More Sports to Be Cut.” CBS Sports, April 15, 2020. Available at: https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/group-of-five- commissioners-ask-ncaa-to-relax-rules-that-could-allow-more-sports-to-be-cut/. (Five Conferences—American Athletic Conference (AAC), Conference USA, Mid-American Conference (MAC), Mountain West Conference, and the Sun Belt Conference—formally requested the NCAA to lower the minimum team requirements for Division 1 membership. The NCAA subsequently denied their request.) See also: ⬧ Hawkins, Stephen. “Slashed St. Ed's: Reeling School Cuts Teams, Breaks Hearts.” ABC News. ABC News Network, May 7, 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/slashed-st-eds-reeling-school- cuts-teams-breaks-70563956. (Saint Edward's University cuts six varsity teams.); ⬧ Keith, Braden. -

Acc/School Information

ACC/SCHOOL INFORMATION SHIPPING/MAILING 4512 Weybridge Lane Greensboro, NC 27407 Phone: 336-854-8787 EMAIL All staff member email address: (first initial and last [email protected]) Exceptions: Andy Fledderjohann ([email protected]) TC Gammons ([email protected]) FAX NUMBERS Administrative/Communications/Football.... 336-854-8797 Championships (Olympic Sports) .................. 336-369-1203 Compliance/Student-Athlete Welfare ............ 336-369-0065 Finance/Administration .................................. 336-316-6097 Office of the Commissioner ........................... 336-547-6268 theACC.com TWITTER: @theACC FACEBOOK: facebook.com/theACC INSTAGRAM/SNAPCHAT: @ACCsports BOSTON COLLEGE NC STATE BCEagles.com GoPack.com Twitter: @BCEagles Twitter: @PackAthletics CLEMSON NOTRE DAME ClemsonTigers.com und.com Twitter: @ClemsonTigers Twitter: @FightingIrish DUKE PITT GoDuke.com PittsburghPanthers.com Twitter: @DukeATHLETICS Twitter: @Pitt_ATHLETICS FLORIDA STATE SYRACUSE Seminoles.com Cuse.com Twitter: @Seminoles Twitter: @Cuse GEORGIA TECH VIRGINIA RamblinWreck.com VirginiaSports.com Twitter: @GTAthletics Twitter: @VirginiaSports LOUISVILLE VIRGINIA TECH GoCards.com HokieSports.com Twitter: @GoCards Twitter: @hokiesports MIAMI WAKE FOREST HurricaneSports.com GoDeacs.com Twitter: @MiamiHurricanes Twitter: @DemonDeacons NORTH CAROLINA GoHeels.com Twitter: @GoHeels 2019-20 Atlantic Coast Conference Officers President: Joe Tront, Virginia Tech Vice-President: Peter Brubaker, Wake Forest Secretary-Treasurer: Tricia Bellia, Notre Dame 2019-20 -

Questions and Answers (Q&A)

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS (Q&A) 17.1.0 SCHOOL YEAR Q&A: When do the WIAA rules take effect? The school year begins on August 1 and ends the first day following the spring sports tournaments. 17.2.2 IN-SEASON Q&A-1: My team did not qualify for postseason playoffs. How long can we continue to practice as a team with our coach? The season concludes with the final day of the state event in for that sport. Even though the team did not qualify, your coach could continue to coach your team until the conclusion of the state tournament for that sport. Q&A-2: Our basketball team is planning to play in a summer basketball tournament on the Sunday after the spring tournaments. With the impending weather reports, the state softball tournament may be postponed until after that date. Will our coach violate the out-of-season rule if she coaches us on Sunday, even though the softball tournament may not be completed? NO. Coaches cannot be responsible for the spring tournament being postponed due to inclement weather. 17.3.4 ALTERNATE SEASON CONTESTS Q&A: Our league plays girls tennis in the fall, but we would like to hold the final district qualifying event one week prior to the state tournament. Is it ok for our team to begin practice 20 school days prior to the district qualifying tournament? NO. Your team may begin practice twenty (20) days prior to the first day of the state tournament, with any contests held only after ten (10) practices have been completed. -

The Athletic Director Survival Guide Kevin M. Bryant, CMAA

The Athletic Director Survival Guide Kevin M. Bryant, CMAA KEVIN BRYANT | 73 Dedication I dedicate this Survival Guide to the following people without which this project would have never seen the light of day. To ‘my person” Sara Ann Bryant, your love and belief in me have often been the difference in my personal success and failure. Thank you for living out God’s love for me in such practical daily ways. In my marriage to you I definitely “out punted my coverage” in winning your heart. To my dearest children Michael, Julie Ann, Megan and Katherine. I have felt your love for me as real as the Oregon rain. Thank you for your encouragement to “finish the race” by following through on this book and my dreams. To the athletic directors, past, present and future in the state of Oregon, you are my inspiration and motivation. Thank you for loving, challenging and encouraging the students, coaches and community members around your athletic program. You are daily difference makers and my hero’s. To Marshall Haskins of the Portland Interscholastic League. Thank you for believing in me and for being my first client. I shall never forget you! To the many people who have had influence in my life (coaches, bosses, close friends, colleagues) your encouragement, challenge, friendship and care have influenced me. Thanks for your belief in me that has led to my best work. The Athletic Director Survival Guide Table of Contents Dedication Preface 1. I have the title Athletic Director, now what? 2. No Surprises 3. Builder or maintainer? 1 4. -

State and District Promotional Toolkit (Pdf)

RESOURCES AND TIPS FOR ADVOCACY OF THE ATHLETIC TRAINING PROFESSION AT THE LOCAL, STATE AND DISTRICT LEVEL. The purpose of this toolkit is to equip state and district athletic trainers’ associations with resources and knowledge to effectively promote At Your Own Risk and advocate for change in their communities through improving awareness of risk and the athletic trainers’ role in risk mitigation. At Your Own Risk is a public awareness campaign for athletic trainers developed by NATA. The mission of At Your Own Risk is to educate, provide resources and equip the public to act and advocate for safety in work, life and sport. Project goals for this initiative include: 1. Create ambassadors for the athletic training profession and for causes championed by athletic trainers. 2. Reinforce the athletic trainer’s position as an authority in athlete safety. 3. Clearly define how key stakeholders can get involved to impact change and improve safety for the physically active athlete and/or worker, given their area(s) of influence. Based on the findings of the 2015 “Athletic Training Services in Public Secondary Schools: A Benchmark Study” which showed that only 37% of public high schools have a full time athletic trainer, secondary schools are the primary emphasis for At Your Own Risk. Key stakeholders for this group include student athletes, parents, school administrators, risk managers and legislators. Over the next 3 years, At Your Own Risk will be rolled out to other settings and stakeholder groups including occupational health, military and the college and university setting. These resources serve as great tools for your association and your members to engage with and educate the public on issues relevant to the athletic training profession.