JOA Journal 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Kustodian Ion Lane Machines Edition 4:12

OPERATORS MANUAL FOR KUSTODIAN ION LANE MACHINES EDITION 4:12 KEGEL LLC. 1951 Longleaf Blvd. Lake Wales, FL 33859 863-734-0200 / 800-280-2695 WARRANTY KEGEL warrants that lane machines and replacement parts will be manufactured free from defects in material and workmanship under normal use and service. Except as stated below, KEGEL shall repair or replace, at its factory or authorized service station, any lane machine or replacement part (“Warranty Item”) which, within ONE YEAR after the date of installation by an authorized KEGEL Distributor, has been determined to be defective upon examination by KEGEL. In no event shall the Warranty coverage be more than twenty-four (24) months from the date of shipment from KEGEL’s factory. In the contiguous United States, the bowling center or end-user will be responsible for requesting Warranty Items from KEGEL and must return Warranty Items directly to KEGEL, following the required procedures. KEGEL will pay reasonable freight charges to deliver and receive Warranty Items from the bowling center. KEGEL will not be responsible for any “expedited” shipping charges. Customer will be invoiced for Warranty Items that are not promptly returned per the required procedures. Outside the contiguous United States, the bowling center or end-user will be responsible for requesting Warranty Items from the DISTRIBUTOR and must return Warranty Items directly to the DISTRIBUTOR, following the required procedures. KEGEL will compensate the DISTRIBUTOR for reasonable freight charges to deliver and receive the Warranty Items from bowling center and to return them to KEGEL. Under no circumstances will KEGEL be responsible for any “expedited” shipping charges or taxes and duties. -

Abstracts Papers Read

ABSTRACTS of- PAPERS READ at the THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING of the AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI DECEMBER 27-29, 1969 Contents Introductory Notes ix Opera The Role of the Neapolitan Intermezzo in the Evolution of the Symphonic Idiom Gordana Lazarevich Barnard College The Cabaletta Principle Philip Gossett · University of Chicago 2 Gluck's Treasure Chest-The Opera Telemacco Karl Geiringer · University of California, Santa Barbara 3 Liturgical Chant-East and West The Degrees of Stability in the Transmission of the Byzantine Melodies Milos Velimirovic · University of Wisconsin, Madison 5 An 8th-Century(?) Tale of the Dissemination of Musico Liturgical Practice: the Ratio decursus qui fuerunt ex auctores Lawrence A. Gushee · University of Wisconsin, Madison 6 A Byzantine Ars nova: The 14th-Century Reforms of John Koukouzeles in the Chanting of the Great Vespers Edward V. Williams . University of Kansas 7 iii Unpublished Antiphons and Antiphon Series Found in the Dodecaphony Gradual of St. Yrieix Some Notes on the Prehist Clyde W. Brockett, Jr. · University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee 9 Mark DeVoto · Unive Ist es genug? A Considerat Criticism and Stylistic Analysis-Aims, Similarities, and Differences PeterS. Odegard · Uni· Some Concrete Suggestions for More Comprehensive Style Analysis The Variation Structure in Jan LaRue · New York University 11 Philip Friedheim · Stat Binghamton An Analysis of the Beginning of the First Movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Op. 8la Serialism in Latin America Leonard B. Meyer · University of Chicago 12 Juan A. Orrego-Salas · Renaissance Topics Problems in Classic Music A Severed Head: Notes on a Lost English Caput Mass Larger Formal Structures 1 Johann Christian Bach Thomas Walker · State University of New York, Buffalo 14 Marie Ann Heiberg Vos Piracy on the Italian Main-Gardane vs. -

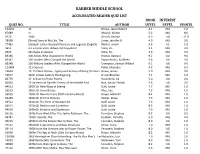

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

Boonshoft Museum of Discovery • Dayton, OH

THIS IS THE HOUSE ROCK BUILT We’re not your typical creative agency. We’re an idea collective. A house of thought and execution. We’re a grab bag of innovators, illustrators, designers and rockstars who are always in pursuit of the big idea! Our building, which was one of the last record stores in America, serves as a playground for our creative minds to frolic and thrive. This is not a design firm. It’s something new and forward-thinking. It’s about going beyond design and messaging. It’s about forging game-changing ideas and harvesting epic results. It’s about YOU. Welcome to U! Creative. U! Creative, Inc Key Contact: (dba: Destination2, The Social Farm) Ron Campbell - President 72 S. Main St. Miamisburg, OH 45342 P: 937.247.2999 Ext. 103 | C: 937.271.2846 P: 937.247.2999 | www.ucreate.us [email protected] UCreative U_Creative in/roncampbell7 U_Creative UCreativeTV That’s because our focus at U! goes beyond providing out-of-the-box thinking. Beyond strategic planning. Beyond creating hard-hitting messaging, engaging design or captivating imagery. Even beyond moving the needle. WE’RE NOT YOUR First and foremost, U! is about building relationships. It’s about unity. It’s about strong ideas and ideals converging. It’s about staying focused on the point of view, needs and desires of others. Because when you get that right, all the rest naturally follows. TYPICAL AGENCY Turn the page and see for yourself. © 2019 U! Creative, Inc. THEthe company COMPANY U! keep U! KEEP © 2019 U! Creative, Inc. -

Rhetorical Concepts and Mozart: Elements of Classical Oratory in His Drammi Per Musica

Rhetorical Concepts and Mozart: elements of Classical Oratory in his drammi per musica A thesis submitted to the University of Newcastle in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Heath A. W. Landers, BMus (Hons) School of Creative Arts The University of Newcastle May 2015 The thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Candidate signature: Date: 06/05/2015 In Memory of My Father, Wayne Clive Landers (1944-2013) Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine: et lux perpetua luceat ei. Acknowledgments Foremost, my sincerest thanks go to Associate Professor Rosalind Halton of the University Of Newcastle Conservatorium Of Music for her support and encouragement of my postgraduate studies over the past four years. I especially thank her for her support of my research, for her advice, for answering my numerous questions and resolving problems that I encountered along the way. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor Conjoint Professor Michael Ewans of the University of Newcastle for his input into the development of this thesis and his abundant knowledge of the subject matter. My most sincere and grateful thanks go to Matthew Hopcroft for his tireless work in preparing the musical examples and finalising the layout of this dissertation. -

LARP Rules for the Dystopia Rising Universe Intended for Use At

LARP Rules for the Dystopia Rising Universe Intended for use at licensed Dystopia Rising events. All rights reserved. 1 Dead-icated to my parents for not seeing gaming as the devil incarnate, to my friends for the support and encouragement to actually get my pet project going, George Romero for redefining the zombie genre, and to Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson for teaching me that the art of telling a story lives forever. Lastly to Ashley, for being my push when I was unsure. Without you this game would have never been anything more than ideas in my head and talk around a hookah. Original World Creation Michael Pucci Executive Producer Ashley Zdeb Contributing Writers Joshua Demers, Megan Jaffe, R.M. Sean Benjamin Jaffe, Mike Malecki, Liam Neary, Ben Przybylinski, Matthew Volk, Matt Wallace, Peter Woodworth Contributing Artists Cryssy Cheung, Zach Herschberger, Joshua Brain Jaffe, Peter Moschel Johnson, Jennifer Lazaroff, Richard Sampson, Andrew Scott, Matthew Volk Layout and Design Matthew Volk Cover Design Joshua Brain Jaffe Copyright 2009-2016 Dystopia Rising LLC All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of Dystopia Rising LLC. All illustrations and images are property of Eschaton Media or used under the allowed rights of public domain. Dystopia Rising is a registered trademark of Michael Pucci and may not be used without written permission of Michael Pucci. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

A Computational Analysis of Information Structure Using Parallel Expository Texts in English and Japanese

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons IRCS Technical Reports Series Institute for Research in Cognitive Science January 1999 A Computational Analysis of Information Structure Using Parallel Expository Texts in English and Japanese Nobo N. Komagata University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports Komagata, Nobo N., "A Computational Analysis of Information Structure Using Parallel Expository Texts in English and Japanese" (1999). IRCS Technical Reports Series. 46. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/46 University of Pennsylvania Institute for Research in Cognitive Science Technical Report No. IRCS-99-07. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/46 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Computational Analysis of Information Structure Using Parallel Expository Texts in English and Japanese Abstract This thesis concerns the notion of 'information structure': informally, organization of information in an utterance with respect to the context. Information structure has been recognized as a critical element in a number of computer applications: e.g., selection of contextually appropriate forms in machine translation and speech generation, and analysis of text readability in computer-assisted writing systems. One of the problems involved in these applications is how to identify information structure in extended texts. This problem is often ignored, assumed to be trivial, or reduced to a sub-problem that does not correspond to the complexity of realistic texts. A handful of computational proposals face the problem directly, but they are generally limited in coverage and all suffer from lack of evaluation. To fully demonstrate the usefulness of information structure, it is essential to apply a theory of information structure to the identification problem and to provide an evaluation method. -

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Big Bang – Shout out to the World!

Big Bang – Shout Out To The World! (English Translation) [2009] Shout out to the World: TOP “I came here because of that string of hope. Where do I stand now? I ask myself this but even I don’t have a specific answer yet. During the process where I search for my other self, all my worries will fade away because I must find the person who will lend his shoulders to me.” ~TOP Name: Choi Seung-hyun Date of Birth: November 4, 1987 Skills: Rap, Writing lyrics, Beatbox *Starred in the KBS Drama, ‘I am Sam’ The power to awaken a soul, sometimes it takes pain to be re-born. [~ Pt.One~] -I once wanted to be a lyric poet that composed and recited verses.- I became mesmerized with ‘Hip-Hop’ music when I was in Grade 5. I went crazy for this type of music because I listened to it all day and carefully noted all the rap lyrics. If we have to talk about Hip-Hop music, I have to briefly talk about the roots of American Hip-Hop. When I first started listening to Hip-Hop, it was divided up into East Coast and West Coast in America. Wu Tang Clan and Notorius B.I.G. represented the East Coast (New York) scene and they focused largely on the rap and the lyrics, while representing the West Coast (LA) was 2Pac who focused more on the melody. Although at that time in Korea and from my memory, more people listened to West Coast hip hop but I was more into the East Coast style. -

JEWELS of the EDWARDIANS by Elise B

JEWELS OF THE EDWARDIANS By Elise B. Misiorowski and Nancy K. Hays Although the reign of King Edward VII of ver the last decade, interest in antique and period jew- Great Britain was relatively short (1902- elry has grown dramatically. Not only have auction 1910), the age that bears his name produced 0 houses seen a tremendous surge in both volume of goods distinctive jewelry and ushered in several sold and prices paid, but antique dealers and jewelry retail- new designs and manufacturing techniques. ers alikereportthat sales inthis area of the industry are During this period, women from the upper- excellent and should continue to be strong (Harlaess et al., most echelons of society wore a profusion of 1992). As a result, it has become even more important for extravagant jewelry as a way of demon- strating their wealth and rank. The almost- jewelers and independent appraisers to understand-and exclusive use of platinum, the greater use of know how to differentiate between-the many styles of pearls, and the sleady supply of South period jewelry on the market. African diamonds created a combination Although a number of excellent books have been writ- that will forever characterize Edwardian ten recently on various aspects of period jewelry, there are jewels. The Edwardian age, truly the last so many that the search for information is daunting. The era of the ruling classes, ended dramatically purpose of this article is to provide an overview of one type with the onset of World War I. of period jewelry, that of the Edwardian era, an age of pros- perity for the power elite at the turn of the 19th century.