Titus Groan As a Queer Figure Against Reproductive Futurity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

Gormenghast Gormenghast

Department of Dramatic Arts Brock University Niagara Region 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1 Canada T 905 688 5550 x5255 brocku.ca October 24, 2016 A Special Invitation to bring your students for innovative and energizing theatre experiences presented by the Department of Dramatic Arts at Brock University! Gormenghast By Mervyn Peake. Stage adaptation by John Constable. Friday, November 18th at 11:30 am Group tickets start at $12 each, discounts available. Twice a year our faculty and students present Mainstage productions in our new 250¬ seat theatre. Directed and designed by faculty and guest artists, performed and produced by students in our Honours BA program, these productions offer you an affordable opportunity to engage your students with original performances that examine provocative thematic ideas. Stimulating course-related content will animate and enrich your teaching curriculum. Our faculty and students bring you the very best of their work in professional-level productions distinguished by their verve and energy. This is a great opportunity to enhance your teaching and to bring excitement to your classroom with a visit to our theatre. Join us at the Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts in our new venue located in downtown St. Catharines, 15 Artists’ Common. Gormenghast By Mervyn Peake. Stage adaptation by John Constable. Directed by Mike Griffin, Assisted by Sydney Francolini Designed by David Vivian Lighting Design by Jennifer Jimenez Sound design by Max Holten-Andersen November 11, 12, 18, 19 at 7:30 pm November 13 at 2:00 pm November 18 at 11:30 am Evil is afoot in the Gormenghast castle! Come join us in this labyrinth of dark corridors, where the bizarre and mysterious come to life. -

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

ERRATA SLIP Mcguinness, Mark (Ed.), Titus Alone

ERRATA SLIP McGuinness, Mark (ed.), Titus Alone: A New Life ISSN 0309 1309 CLAIRE PEÑATE (PEAKE) – INTRODUCTION line 1, for ‘Titus Alone’ read Titus Alone (ditto lines 15, 22) line 2, for Father read father (ditto lines 5, 24, 31, 33) line 6, for Mother read mother line 7, for that read and line 10, for Titus Groan read Titus Groan line 12, for characters read characters’ line 13, for writs read write line 20, for have read had line 21, for ‘Gormengast’ read Gormenghast line 21, for thought read thought. line 32, for Titus Alone read Titus Alone NICK FREEMAN - ‘THE INTER-WAR ROOTS OF TITUS ALONE’ Bibliography line 2, for Aldington, Richard read Fussell, Paul PIERRE-YVES LE CAM – ‘THE SCIENCE FICTION WORLD OF TITUS ALONE’ Two pages are missing from this article, printed below. The bold text appears in the printed book, and the normal face text is missing. ‘The time gap justifies the new standards and techniques, however incredible they may appear to the contemporary world. Peake's originality consists in doubling the temporal distortion which affects not only the reader but also Titus. The reader senses in the science to come the technological achievements in Titus Alone such as the laser weapon; Titus moves from a medieval environment to a futuristic one, and the earl's wonder is obvious when he sees the scores of rockets or the metal and marble architecture of the dome and the arena: (There) was a copper dome the shape of an igloo but ninety feet in height, with a tapering mast, spider-frail and glinting in the sunlight (...). -

The Last Station

Mongrel Media Presents The Last Station A Film by Michael Hoffman (112 min, Germany, Russia, UK, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. Using every bit of cunning, every trick of seduction in her considerable arsenal, she fights fiercely for what she believes is rightfully hers. -

00 Peak Gormenghast-Bd3-B.Indb

MERV YN PEAK E DrittesDrittes Buch DER LETZTE LORD GROAN Aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Annette Charpentier Klett-Cotta Die Übersetzung von Annette Charpentier wurde für diese Ausgabe neu durchgesehen von Alexander Pechmann. Hobbit Presse www.klett-cotta.de/hobbitpresse Die Originalausgabe erschien unter dem Titel »Titus Alone« im Verlag Eyre & Spottiswoode, London © 1959 by Mervyn Peake Für die deutsche Ausgabe © 1983 by J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger GmbH, gegr. 1659, Stuttgart Alle deutschsprachigen Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany Schutzumschlag: HildenDesign, München, www.hildendesign.de Artwork: © Birgit Gitschier, HildenDesign unter Verwendung mehrerer Motive von Shutterstock Gesetzt aus der Galliard von Elstersatz, Wildfl ecken Gedruckt und gebunden von GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck ISBN 978-3-608-93923-1 Erste Aufl age der neu durchgesehenen Ausgabe, 2011 Inhalt Vorwort von Michael Moorcock 9 Gormenghast Drittes Buch Der letzte Lord Groan 13 Nachwort der englischen Ausgabe 327 ~ 7 ~ Vorwort von Michael Moorcock Der letzte Lord Groan ist für mich in vielerlei Hinsicht das inter- essanteste der drei Bücher, die Mervyn Peake über den jungen Grafen von Gormenghast schrieb, auch wenn seine Handlung nicht so packend ist wie jene der ersten beiden. Obwohl es eini- ge Jahre lang für das schwächste gehalten wurde, weil ein ver- ständnisloser Lektor es verunstaltet hatte, während Peake sich in den ersten Stadien der Parkinson-Krankheit befand, erwies es sich in der restaurierten Fassung als weitaus besser, als die Kritiker ursprünglich geurteilt hatten. Wenn der Autor und Anthologist Langdon Jones, damals Mitherausgeber der Zeitschrift New Worlds, nicht Peakes Ori- ginalmanuskript durchgeblättert und deutliche Abweichungen zwischen der geschriebenen und der gedruckten Version ge- funden hätte, dann wäre die vorliegende weitaus vollstän digere Fassung nie veröffentlicht worden. -

01 to 06 MAY Terry Waite

Mark Billingham Ross Collins Kerry Brown Maura Dooley Matt Haig Darren Henley Emma Healey Patrick Gale Guernsey Literary Erin Kelly Huw Lewis-Jones Adam Kay Kiran Millwood Hargrave Kiran FestivalLibby Purves 2019 Lionel Shriver Philip Norman Philip 01 TO 06 MAY Terry Waite Terry Chrissie Wellington Piers Torday Lucy Siegle Lemn Sissay MBE Jessica Hepworth Benjamin Zephaniah ANA LEAF FOUNDATION MOONPIG APPLEBY OSA RECRUITMENT BROWNS ADVOCATES PRAXISIFM BUTTERFIELD RANDALLS DOREY FINANCIAL MODELLING RAWLINSON & HUNTER GUERNSEY ARTS COMMISSION ROTHSCHILD & CO GUERNSEY POST SPECSAVERS JULIUS BAER THE FORT GROUP Sophy Henn Kindly sponsored by sponsored Kindly THE INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE THE GUERNSEY SOCIETY Turning the Tide on Plastic: How St James: £10/£5 Lucy Siegle Humanity (And You) Can Make Our Welcome to the Globe Clean Again seventh Guernsey Presenter on BBC’s The One Show and columnist for the Observer and the Guardian, Lucy Siegle offers a unique and beguiling perspective on environmental issues and ethical consumerism. Turning the Tide on Literary Festival Plastic provides a powerful call to arms to end the plastic pandemic along with the tools we need to make decisive change. It is a clear- eyed, authoritative and accessible guide to help us to take decisive and 13:00 to 14:00 effective personal action. Thursday 2 May Message from Sponsored by PraxisIFM Message from Claire Allen, Terry Waite CBE OGH Hotel: £25 Festival Director This is Going to Hurt Business Breakfast As Honorary I am very proud to welcome Professor Kerry you to the seventh Guernsey Chairman of the Literary Festival! With over Adam Kay Thursday 2 May Brown: The World Guernsey Literary 19:30 to 20:30 60 events for all interests According to Xi Festival it is once and ages, the festival is a Kerry Brown is Professor of again my pleasure unique opportunity to be inspired by writers. -

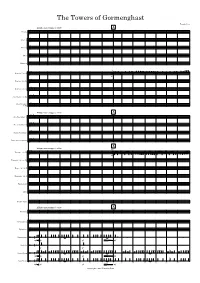

The-Towers-Of-Gormenghast-Web.Pdf

The Towers of Gormenghast Timothy Rees Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Piccolo ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 1 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 2 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bassoon ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Tpt. j j j j j œ œ Clarinet 1 in Bb ° # 6 Œ™ Œ j œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ & # 8 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ œ œ œ œ ∑ mf ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 2 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Clarinet in Eb # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bass Clarinet # in Bb # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Alto Saxophone 1 ° # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Saxophone 2 # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tenor Saxophone # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Baritone Saxophone # # # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 A Allegro non troppo q . = 108 solo Trumpet 1 in Bb ° # j j œ œ œ j œ œ œ œ & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ™ Œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ mfœ œ J J J œ J J Trumpet 2 & 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Horn 1 & 2 in F # & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Trombone 1 & 2 ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Euphonium ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tuba ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Double Bass ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Timpani °? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Glockenspiel ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ -

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected]

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected] - www.beckyshrimpton.com Agent – Paul Smith - ETM HEIGHT: 5’5’’ WEIGHT: 140 lbs HAIR: Dark Brown EYES: Green SELECTED FILM & TELEVISION Stress Vaccine Lead Tom Mae/Tom Mae Productions Be Alert Bert – Martial Arts Lead Lisa Lovatt/ITV Be Alert Bert – Shoplifting Lead James Martins/ITV The Ghost is a Lie Lead Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Surviving Evil – Season 2 Episode 4 Principal Emily/Schooley/Laughing Cat Productions Giving You the Business Season 1 Episode 8 Principal Joel Goldberg/FoodNetwork USA Canada! Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Irresistible Force Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Mask-a-raid Principal Liza Callahan/VFS Productions Cutaway Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films The Missing Me Principal Attila Kallai/Atka Films The Drinking Helps Principal Josh Kingston/Mom's Proud Productions Tower Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films Inspiration Actor Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Films Strange Famous Music Video Actor Dustin Kuypers/The Documentarians Motives and Murders Season 5 Episode 6 Actor Cineflix Productions SELECTED ANIMATION VOICE OVER Fireman Sam Helen Flood Susan Hart/Kitchen Sync Mage and Minions Female Heroes John Welch/Making Fun Inc. Doki Multiple Characters Susan Hart/Investigation Kids Brambleberry Tales Narrator David Lam/Rival Schools Firefall Nina Ian Macmillan/VFS Productions HellBent Beatrix Samantha Satiago/Ringling Animations DecorView Kate Chad Parker/FunnelBox Media Ring Run Circus Nina Sebastian Fernandez/Kalio Productions -

A PHILOSOPHICAL Enquiry INTO SOME ASPECTS of the TEACHER's ROLE Helen Stephanie Freeman

1 A PHILOSOPHICAL ENqUIRY INTO SOME ASPECTS OF THE TEACHER'S ROLE Helen Stephanie Freeman - 2 - J36TRACT In this thesis an investigation is conducted into the justification for various aspects of the teacher's role in schools, being concerned in particular to find out whether certain aspects are in some way necessary for the role as a justifiable one in a justifiable institution. That thesis is, itself, an instantiation of a further thesis concerned with the prescriptive implications of philosophy of education, which is discussed in the first section. The second section discusses what it is to be teaching someone something, raising objections to the current orthodox analysis of the concept of teaching, which is argued to be inadequate to account for our current understanding of it. Various terms of art are considered and found unsatisfactory, and a new schema for analysing teaching is introduced. An alternative analysis which does not embody certain important assumptions of the orthodox analysis is presented. Objections to it are considered. The third section examines the concept of role, using as its basis an analysis presented by R.S. Downie. This analysis is considered to be too crude for the investigation of this thesis, and an alternative analysis is again developed for application here. Some of the problems of role concepts are discussed in relation to the social sciences. The fourth section applies the above analyses to a consideration of the teacher's role in respect of the following aspects: (a) the teaching of understanding, beliefs and skills (including the specifying of low-level objectives) (b) the teaching of values (c) assessment and evaluation (d) authority in the sphere of knowledge and, briefly, the personal/impersonal dimension of the teacher-pupil relationship. -

Key Stage Three What Could I Read Next?

Key Stage Three What could I read next? Titles marked with *** are more of a challenge read - challenge yourself to read some of these! Titles in red can be found in the LRC. Fantasy and Science-Fiction C. S. Lewis, The Chronicles of Narnia Douglas Adams, The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy *** H.G. Wells, The Time Machine Jack Finney, Invasion of the Body Snatchers J. R. R. Tolkein, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings Jules Verne, Journey to the Centre of the Earth and 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Lemony Snickett, A Series of Unfortunate Event Mervyn Peake, Gormenghast Trilogy(Titus Groan, Gormenghast &Titus Alone) P. D. James, The Children of Men Philip Pullman, His Dark Materials Trilogy (Northern Lights, The Subtle Knife & The Amber Spyglass) JK Rowling Harry Potter Series Tony Diterlizzi, The Search for Wondla Cornelia Funke, Inkdeath Philip Reeve, Goblins Eva Ibbotson, The Ogre of Oglefort Julia Golding, Secret of the Sirens AJ Lake, The coming of dragons Kenneth Grahame, The reluctant dragon Mark Robson, Firestorm Dugald Steer, The dragon's eye Templar Cressida Cowell, A hero's guide to deadly Horrendous Haddock III Philip Reeve, No such thing as dragons Kaye Umansky, The dreadful dragon Toby Forward, Dragonborn Walker Chris Mould, Fangs 'n' fire : ten dramatic dragon tales Lucinda Hare, The dragon whisperer Margaret Bateson-Hill, Dragon racer Dan Abnett, Dragon frontier Elizabeth Kay, The divide Chicken House Historical Fiction Michael Morpugo, Private Peaceful Philippa Gregory, The Other Boleyn Girl Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff Nevil Shute A Town like Alice Tracy Chavalier, The Girl with the Pearl Earing Michelle Magorian Goodnight Mister Tom Family and Relationships Sharon Creech, Heartbeat Bali Rai, (Un)Arranged Marriage Kevin Crossley Holland, Gatty’s Tale Mary Hooper, At the Sign of the Sugared Plum Tanya Landman, Apache: Girl Warrior *** J. -

Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone Ebook Free Download

THE GORMENGHAST NOVELS: TITUS GROAN / GORMENGHAST / TITUS ALONE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mervyn Laurence Peake | 1168 pages | 01 Dec 1995 | Overlook Press | 9780879516284 | English | New York, United States The Gormenghast Novels: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone PDF Book Tolkien, but his surreal fiction was influenced by his early love for Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson rather than Tolkien's studies of mythology and philology. It was very difficult to get through or enjoy this book, because it feels so very scattered. But his eyes were disappointing. Nannie Slagg: An ancient dwarf who serves as the nurse for infant Titus and Fuchsia before him. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. I honestly can't decide if I liked it better than the first two or not. So again, mixed feelings. There is no swarmer like the nimble flame; and all is over. How does this vast castle pay for itself? The emphasis on bizarre characters, or their odd characteristics, is Dickensian. As David Louis Edelman notes, the prescient Steerpike never seems to be able to accomplish much either, except to drive Titus' father mad by burning his library. At the beginning of the novel, two agents of change are introduced into the stagnant society of Gormenghast. However, it is difficult for me to imagine how such readers could at once praise Peake for the the singular, spectacular world of the first two books, and then become upset when he continues to expand his vision. Without Gormenghast's walls to hold them together, they tumble apart in their separate directions, and the narrative is a jumbled climb around a pile of disparate ruins.