Background Checks for Firearms Sales and Loans: Law, History, and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F:\Assault Weapons\On Target Brady Rebuttal\AW Final Text for PDF.Wpd

A Further Examination of Data Contained in the Study On Target Regarding Effects of the 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban Violence Policy Center The Violence Policy Center (VPC) is a national non-profit educational organization that conducts research and public education on firearms violence and provides information and analysis to policymakers, journalists, advocates, and the general public. The Center examines the role of firearms in America, analyzes trends and patterns in firearms violence, and works to develop policies to reduce gun-related death and injury. Past studies released by the VPC include: C Really Big Guns, Even Bigger Lies: The Violence Policy Center’s Response to the Fifty Caliber Institute’s Misrepresentations (March 2004) • Illinois—Land of Post-Ban Assault Weapons (March 2004) • When Men Murder Women: An Analysis of 2001 Homicide Data (September 2003) • Bullet Hoses—Semiautomatic Assault Weapons: What Are They? What’s So Bad About Them? (May 2003) • “Officer Down”—Assault Weapons and the War on Law Enforcement (May 2003) • Firearms Production in America 2002 Edition—A Listing of Firearm Manufacturers in America with Production Histories Broken Out by Firearm Type and Caliber (March 2003) • “Just Like Bird Hunting”—The Threat to Civil Aviation from 50 Caliber Sniper Rifles (January 2003) • Sitting Ducks—The Threat to the Chemical and Refinery Industry from 50 Caliber Sniper Rifles (August 2002) • License to Kill IV: More Guns, More Crime (June 2002) • American Roulette: The Untold Story of Murder-Suicide in the United States (April 2002) • The U.S. Gun Industry and Others Unknown—Evidence Debunking the Gun Industry’s Claim that Osama bin Laden Got His 50 Caliber Sniper Rifles from the U.S. -

National Shooting Sports Foundation Inc. As Amicus Curiae in Support of the Petitioners ______

No. 20-843 In the Supreme Court of the United States _____________ NEW YORK STATE RIFLE & PISTOL ASSOCIATION, INC., ROBERT NASH, BRANDON KOCH, PETITIONERS v. KEVIN P. BRUEN, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW YORK STATE POLICE, RICHARD J. MCNALLY JR., IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS JUSTICE OF THE NEW YORK SUPREME COURT, THIRD JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AND LICENSING OFFICER FOR RENSSELAER COUNTY, RESPONDENTS _____________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT _____________ BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL SHOOTING SPORTS FOUNDATION INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONERS _____________ LAWRENCE G. KEANE JONATHAN F. MITCHELL National Shooting Counsel of Record Sports Foundation Inc. Mitchell Law PLLC 400 North Capitol Street 111 Congress Avenue Suite 475 Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20001 Austin, Texas 78701 (202) 220-1340 (512) 686-3940 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae QUESTION PRESENTED The Second Amendment provides that “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” U.S. Const. amend. II; see also McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010) (incorporating the Second Amendment against the States). The State of New York prohibits indi- viduals from carrying pistols or revolvers outside the home unless they obtain a license, and it prevents these licenses from being granted unless the applicant demon- strates “proper cause for [its] issuance.” N.Y. Penal Law § 400.00(2)(f). The statute does not define “proper cause,” but the courts of New York interpret this phrase to re- quire an applicant to “demonstrate a special need for self- protection distinguishable from that of the general com- munity or of persons engaged in the same profession.” Klenosky v. -

Universal Background Checks” & Burdening Access to Human Rights Written By: Matthew Larosiere, Joseph Greenlee, and Adam Kraut

2 FIREARMS POLICY COALITION FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 3 “Universal Background Checks” & Burdening Access to Human Rights written by: matthew larosiere, joseph greenlee, and adam kraut Executive Summary transfers to prohibited persons; law-abiding people already follow those laws, while criminals already “ niversal background checks” require that a violate them. Ubackground check be conducted anytime a fire- Nor do universal background checks address the arm is transferred between two private parties.1 Fed- problem of mass-shootings—which constitute an eral law already requires anyone who purchases a exceedingly small percentage of gun violence and a firearm from a licensed dealer to undergo a back- mere fraction of homicides to begin with. Nearly ground check.2 Universal background checks extend every mass-shooter in recent history would have—or that requirement to purely private and intrastate did—pass a background check, and a few that back- transactions. ground checks should have prevented passed the Background checks are relatively recent gun con- check anyway, because the system failed. trols. There is no colonial or founding era basis for That universal background checks would have lit- such laws, aside from discriminatory restrictions on tle effect on crime is especially problematic when persons who were not considered citizens. Rather considering the burden they place on law-abiding than require government permission to own fire- individuals. Background checks make it more diffi- arms, the historical practice in America was for the cult and more expensive to acquire a firearm for government to require firearm ownership. Only in self-defense, to lend a firearm to a family member or the twentieth century did some states start requiring friend in danger, to train with firearms at the gun all purchasers to demonstrate good moral character, range, and to share a firearm when hunting. -

Patterns of Gun Trafficking

Patterns of gun trafficking: An exploratory study of the illicit markets in Mexico and the United States A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Security Science David Pérez Esparza Department of Security and Crime Science Faculty of Engineering Sciences University College London (UCL) September, 2018 1 Declaration I, David Pérez Esparza confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis aims to explain why, against the background of a fairly global crime drop, violence and crime increased in Mexico in the mid-2000s. Since most classical hypotheses from criminological research are unable to account satisfactorily for these trends, this study tests the explanatory power of a situational hypothesis as the main independent variable (i.e. the role of opportunity). In particular, this involves testing whether the rise in violence can be explained by an increase in the availability of illegal weapons in Mexico resulting from policy changes and rises in gun production in the bordering U.S. To conduct this study, the thesis develops and implements an ad hoc analytic strategy (composed of six steps) that helps to examine each gun market (i.e. pistols, revolvers, rifles, and shotguns) both in the supply (U.S.) and in the illegal demand for firearms (Mexico). Following this market approach, the study finds that patterns of gun production in the U.S. temporally and spatially coincide with the patterns of gun confiscation (and violent crime) in Mexico. -

Curio & Relic/C&R Information for Collectors

Page 1 JULY 2020 Columns & News The GunNews is the official monthly publication of the Washington 4 Legislation & Politics–Joe Waldron Arms Collectors, an NRA-affiliated organization located at 1006 15 Straight From the Holster–JT Hilsendeger Fryar Ave, Bldg D, Sumner, WA 98390. Subscription is by member- 18 Is There a Mouse in Your House?–Tom Burke ship only and $15 per year of membership dues goes for subscrip- 22 Short Rounds tion to the magazine. Features Managing Editor–Philip Shave 3 Curio & Relic License Information–Editor Send editorial correspondence, Wanted Dead or 8 The Red 9–Bill Hunt Alive ads, or commercial advertising inquiries to: 10 The Chinese .45 Broomhandle–J.W. Mathews [email protected] 12 A Broomhandle By Any Other Name–Phil 7625 78th Loop NW, Olympia, WA 98502 Shave (360) 866-8478 Assistant Editor–Bill Burris For Collectors Art Director/Covers–Bill Hunt Cover–Art Director Copy Editors–Bob Brittle, Bill Burris, Forbes 24 Wanted: Dead or Alive Bill Hunt provided Freeburg, Woody Mathews 32 Show Calendar both the cover photo and article on the Member Resources Mauser C96 Red 9, see pp. 8-9, 16-17. CONTACT THE BUSINESS OFFICE FOR: 28 Board Minutes n MISSING GunNews & DELIVERY PROBLEMS 30 Member Info n TABLE RESERVATIONS n CHANGE OF ADDRESS n TRAINING n CLUB INFORMATION, MEMBERSHIP Club Officers (425) 255-8410 voice President — Bill Burris (425) 255-8410 253-881-1617FAX Vice President — Boyd Kneeland (425) 643-9288 Office Hours: 9a.m.–5p.m., M–TH Secretary — Forbes Freeburg (425) 255-8410 closed holidays Treasurer — Holly Henson (425) 255-8410 Walk-in Temporarily Closed Due to Immediate Past President — Boyd Kneeland (425) 643-9288 Virus Club Board of Directors SEND OFFICE CORRESPONDENCE TO: Scott Bramhall (425)255-8410 P.O. -

Centralized Firearms Background Check Program Implementation Plan

CENTRALIZED FIREARMS BACKGROUND CHECK PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION PLAN December 1, 2020 Developed by: Scott Came Consulting LLC in partnership with SEARCH and Briskin Consulting LLC THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK CENTRALIZED FIREARMS BACKGROUND CHECK PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 3 Program Overview ......................................................................................................... 4 System Description........................................................................................................ 5 Assumptions and Constraints ........................................................................................ 6 Scope and Organizational Assumptions ........................................................................ 6 Assumptions Concerning the Volume of Background Checks ....................................... 8 Budget Assumptions .................................................................................................... 11 Technology Assumptions............................................................................................. 12 Constraints .................................................................................................................. 13 Program Organization ................................................................................................ -

A Content Analysis of the Coverage of Gun Trafficking Along

A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE COVERAGE OF GUN TRAFFICKING ALONG THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER A Dissertation by OMAR CAMARILLO Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Holly Foster Committee Members, Sarah N. Gatson Jane Sell Alex McIntosh Head of Department, Jane Sell May 2015 Major Subject: Sociology Copyright 2015 Omar Camarillo ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzed how the media on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border portrayed the issue of gun trafficking’s into Mexico and its impact on Mexico’s border violence. National newspapers from both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border were analyzed from January 2009 through January 2012, The New York Times for the U.S. and El Universal for Mexico, which resulted in a sample of 602 newspaper articles. Qualitative research methods were utilized to collect and analyze the data, specifically content analysis. Drawing on a theoretical framework of social problems and framing this study addressed how gun trafficking along the U.S.-Mexico border impacted the drug related violence that is ongoing in Mexico, how gun trafficking was portrayed as a social problem by the media, and how the media depicted the victims of drug related violence. This study revealed six framing devices, “the blame game,” “worthy and unworthy victims,” “positive aspects of gun trafficking,” “negative aspects of gun trafficking,” “indirect mention of gun trafficking,” and “direct mention of gun trafficking” that were utilized by The New York Times and El Universal to discuss and frame the issue gun trafficking into Mexico and its impact on Mexico’s border violence. -

Application for Federal Firearms License

U.S. Department of Justice OMB No. 1140-0018 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Application for Federal Firearms License For ATF Use Only 1. Name of Owner or Corporation (If partnership, include name of each partner) 2. Trade or Business Name, if any 3. Employer Identification Number (EIN#) or 4. Name of County in Which Social Security Number (SSN is Voluntary) Business is Located 5. Business Address (RFD or street number, city, State, and ZIP 6. Mailing Address (If different from address in item #5) code) (NOTE: The business address CANNOT be a P.O. Box.) 7. Contact Numbers (Include Area Code) Business Phone Fax Number Cell Phone 24 Hour Emergency # (If different) 8. Applicant's Business is (Select one) Individually Owned A Partnership A Corporation Other (Specify) 9. Describe Specific Activity Applicant is Engaged in, or Intends to Engage in, Which Requires a Federal 10. Do You Intend to Engage in Firearms License. (Sale of ammunition alone does not require a license.) Business as a Pawnbroker? Yes No 11. Application is Made For a License Under 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44 as a: (Place an "X" in the appropriate box. Submit the fee noted next to the box with the application. Licenses are issued for a 3-year period. See instruction #13 for payment information.) Type Description of License Type Fee Dealer (01), Including Pawnbroker (02), in Firearms Other Than Destructive Devices (Includes: Rifles, Shotguns, Pistols, 01/02 $200 Revolvers, Gunsmith activities and National Firearms Act (NFA) Weapons) 06 Manufacturer of Ammunition -

Application for Federal Firearms License

OMB No. 1140-0018 U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Application for Federal Firearms License Part A 1. Applicant’s Business/Activity is: Individual Owner (Sole Proprietor) Partnership Corporation LLC Collector (which can be an individual/partnership/corporation or LLC) Other (specify) 2. Licensee Name (Enter name of Owner/Sole Proprietor OR Partnership (include name of each partner) OR Corporation Name OR LLC Name) 3. Trade or Business Name(s), if any 4. Employer Identification Number 5. Name of County in which (EIN), if any (see definition #17) Business/Activity is Located 6. Business/Activity Address (RFD or Street Number, City, State, 7. Mailing Address (if different from address in item #6) and ZIP Code) (NOTE: This address CANNOT be a P.O. Box.) 8. Contact Numbers (Include Area Code) Business/Activity Phone Fax Number Cell Phone Business Email 9. Describe the specific activity applicant is engaged in or intends to engage in, which requires a Federal Firearms License (sale of ammunition alone does not require a Federal Firearms License). 10. Application is made for a license under 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44 as a: (Place an “X” in the appropriate box(es). Multiple license types may be selected- see instruction #8. Submit the fee noted next to the box(es) with the application. Licenses are issued for a 3-year period. See instruction #5 for payment information). Type Description of License Type Fee Dealer in Firearms Other than Destructive Devices (Includes: rifles, shotguns, pistols, revolvers, -

Federal Firearms Regulations Reference Guide

AFT U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Enforcement Programs and Services 2014 2014 ATF Publication 5300.4 Revised September 2014 U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Office of the Director Washington, DC 20226 Dear Federal Firearms Licensees: The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), a component of the United States Department of Justice, is a law enforcement agency charged with protecting our communities from violent criminals, criminal organizations, the illegal possession, use and trafficking of firearms, the illegal possession, use and storage of explosives, acts of arson and bombings, and the illegal diversion of alcohol and tobacco products. We are proud to partner with industries, law enforcement, and the community to protect the public we serve. Federal firearms licensees play a key role in safeguarding the public from violent crime by maintaining accurate records, instituting internal controls, and performing background checks on potential firearms purchasers. These practices have saved lives, prohibited violent criminals from obtaining firearms, and prevented firearms-related crimes. The 2014 edition of the Federal Firearms Regulations Reference Guide contains information that will help you comply with Federal laws and regulations governing the manufacture, importation and distribution of firearms and ammunition. This edition contains new and amended statutes enacted since publication of the 2005 edition, as well as updated regulations and rulings issued by ATF. In addition to these updated materials, in response to inquiries received from industry members, the public, and partner agencies, the 2014 edition contains additional and amended Questions and Answers to assist with compliance. -

Libertarian Party of Erie County V. Cuomo, 970 F.3D 106 (2Nd Cir

No. ______ ______________________________________________________________________________ In The Supreme Court of the United States ______________________________________________________ Libertarian Party of Erie County, Michael Kuzma, Richard Cooper, Ginny Rober, Philip M. Mayor, Michael Rebmann, Edward L. Garrett, David Mongielo, John Murtari, William Cuthbert, Petitioners, v. Andrew M. Cuomo, individually and as Governor of the State of New York, Letitia James, individually and as Attorney General of the State of New York, Joseph A. D'Amico, individually and as Superintendent of the New York State Police, et al. Respondents. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari To the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ______________________________________________________ PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI ______________________________________________________ James Ostrowski Counsel of Record Buffalo, New York 14216 MICHAEL KUZMA (716) 435-8918 1893 Clinton St. [email protected] Buffalo, New York 14206 (716) 822-7645 michaelkuzmaesq @gmail.com Counsel for Petitioners i QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW This case presents one big issue that necessarily requires the resolution of a number of critical subsidiary issues. 1. Should the State of New York, in all of its three branches of government, working in unison, be allowed to continue to blatantly violate the right to bear arms as recognized by this Court in the landmark decisions of District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008) and McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010), through its arbitrary, complex and onerous pistol permit process which forces citizens to seek the permission of neighbors, police officers and licensing officials to exercise a fundamental right and which vests in licensing officials virtually unlimited discretion to deny, suspend or revoke handgun permits while ignoring due process, and which forces citizens to endure a lengthy, expensive and complex permit application process? Resolving this question requires the resolution of the following additional questions: 2. -

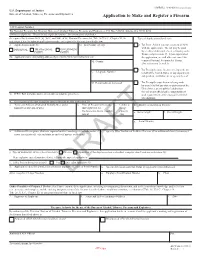

Application to Make and Register a Firearm

OMB No. 1140-0011 (xx/xx/xxxx) U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Application to Make and Register a Firearm ATF Control Number To: National Firearms Act Division, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, P.O. Box 530298, Atlanta, GA 30353-0298 (Submit in duplicate. Please do not staple documents. See instructions attached.) As required by Sections 5821 (b), 5822, and 5841 of the National Firearms Act, Title 26 U.S.C., Chapter 53, the 1. Type of Application (check one) undersigned hereby submits application to make and register the firearm described below. 2. Application is made by: 3a. Trade name (If any) a. Tax Paid. Submit your tax payment of $200 with the application. The tax may be paid INDIVIDUAL TRUST or LEGAL GOVERNMENT by credit or debit card, check, or money order. ENTITY ENTITY Please complete item 17. Upon approval of 3b. Applicant’s name and mailing address (Type or print below) (see instruction 2d) the application, we will affix and cancel the 3d. County required National Firearms Act Stamp. (See instruction 2c and 3) b. Tax Exempt because firearm is being made on 3e. Telephone Number behalf of the United States, or any department, independent establishment, or agency thereof. 3f. E-mail address (optional) c. Tax Exempt because firearm is being made by or on behalf of any State or possession of the United States, or any political subdivision thereof, or any official police organization of 3c. If P.O. Box is shown above, street address must be given here such a government entity engaged in criminal investigations.