Pre-Strategy Assessment of the Moldovan Wine Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

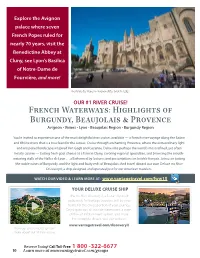

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

Burgundy Beaujolais

The University of Kentucky Alumni Association Springtime in Provence Burgundy ◆ Beaujolais Cruising the Rhône and Saône Rivers aboard the Deluxe Small River Ship Amadeus Provence May 15 to 23, 2019 RESERVE BY SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 SAVE $2000 PER COUPLE Dear Alumni & Friends: We welcome all alumni, friends and family on this nine-day French sojourn. Visit Provence and the wine regions of Burgundy and Beaujolais en printemps (in springtime), a radiant time of year, when woodland hillsides are awash with the delicately mottled hues of an impressionist’s palette and the region’s famous flora is vibrant throughout the enchanting French countryside. Cruise for seven nights from Provençal Arles to historic Lyon along the fabled Rivers Rhône and Saône aboard the deluxe Amadeus Provence. During your intimate small ship cruise, dock in the heart of each port town and visit six UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the Roman city of Orange, the medieval papal palace of Avignon and the wonderfully preserved Roman amphitheater in Arles. Tour the legendary 15th- century Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, famous for its intricate and colorful tiled roof, and picturesque Lyon, France’s gastronomique gateway. Enjoy an excursion to the Beaujolais vineyards for a private tour, world-class piano concert and wine tasting at the Château Montmelas, guided by the châtelaine, and visit the Burgundy region for an exclusive tour of Château de Rully, a medieval fortress that has belonged to the family of your guide, Count de Ternay, since the 12th century. A perennial favorite, this exclusive travel program is the quintessential Provençal experience and an excellent value featuring a comprehensive itinerary through the south of France in full bloom with springtime splendor. -

Russian Wine / Российские Вина

3 RUSSIAN WINE RUSSIAN WINE / РОССИЙСКИЕ ВИНА SPARKLING / ИГРИСТЫЕ 750 ML NV Балаклава Резерв Брют Розе, Золотая Балка 2 500 2017 Кюве Империал Брют, Абрау-Дюрсо 4 700 2016 Темелион Брют Розе, Лефкадия 5 520 NV Тет де Шеваль Брют, Поместье Голубицкое 5 700 2020 Пет-Нат, Павел Швец 6 500 2016 Блан де Нуар Брют, Усадьба Дивноморское 7 900 WHITE / БЕЛОЕ 750 ML 2020 Терруар Блан, Гай-Кодзор / Гай-Кодзор 2 700 2019 Сибирьковый, Винодельня Ведерников / Долина Дона 3 100 2020 Алиготе, Бельбек / Плато Кара-Тау, Крым 3 500 2019 Хихви, Собер Баш / Долина Реки Афипс 3 700 2019 Мускат, Рэм Акчурин / Долина Реки Черная, Крым 4 000 2018 Шардоне, Абрау-Дюрсо / Абрау-Дюрсо 4 700 2019 Шардоне Резерв, Поместье Голубицкое / Таманский Полуостров 5 100 2019 Совиньон Блан, Галицкий и Галицкий / Красная Горка 5 500 2020 Шенен Блан, Олег Репин / Севастополь, Крым 5 700 2017 Рислинг - Семейный Резерв, Имение Сикоры / Семигорье 6 000 2017 Пино Блан, Усадьба Дивноморское / Геленджик 6 800 2020 Ркацителли Баррик, Бельбек / Плато Кара-Тау, Крым 7 200 2018 Вионье, Лефкадия / Долина Лефкадия 8 500 ROSE / РОЗОВОЕ 750 ML 2020 Розе де Гай-Кодзор / Гай-Кодзор 2 700 2020 Аврора, Собер Баш / Долина Реки Афипс 3 100 2019 Розе, Галицкий и Галицкий / Красная Горка 5 000 RED / КРАСНОЕ 750 ML 2018 Мерло Резерв, Балаклава / Севастополь, Крым 3 300 2019 Каберне Совиньон - Морской, Шато Пино / Новоросийск 3 700 2019 Пино Минье - Резерв, Яйла / Севастополь, Крым 4 000 2019 Пино Нуар, Андрюс Юцис / Севастополь, Крым 4 500 2017 Афа, Собер Баш / Долина Реки Афипс 5 000 2019 Каберне -

Pre-Trip Extension Itinerary

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Enhanced! Northern Greece, Albania & Macedonia: Ancient Lands of Alexander the Great 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Enhanced! Northern Greece, Albania & Macedonia: Ancient Lands of Alexander the Great itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: As I explored the monasteries of Meteora, I stood in awe atop pinnacles perched in a boundless sky. I later learned that the Greek word meteora translates to “suspended in the air,” and that’s exactly how I felt as I stood before nature’s grandeur and the unfathomable feats of mankind. For centuries, monks and nuns have found quiet solitude within these monasteries that are seemingly built into the sandstone cliffs. You’ll also get an intimate view into two of these historic sanctuaries alongside a local guide. Could there be any place more distinct in Europe than Albania? You’ll see for yourself when you get a firsthand look into the lives of locals living in the small Albanian village of Dhoksat. First, you’ll interact with the villagers and help them with their daily tasks before sharing a Home-Hosted Lunch with a local family. While savoring the fresh ingredients of the region, you’ll discuss daily life in the Albanian countryside with your hosts. -

''The Only Fault of Wine Is That There Is Always a Lack of Wine''

Ukrainian WineHub #1 at Eastern 2020 Europe rinks market! page 7 clockOnline Newspaper: Eastern news and Western trends www.drinks.uaD Christian ‘‘The only fault Wolf: ‘MUNDUS VINI feels like Oa family’ of is that wine page14 there is always a lack of wine’’ Legend of Ukraine is not Georgia, that’s true. Yes, this country is not Saracena: a cradle of wine and cannot boast of its 8-thousand-year Drink less, read more! a unique peerless history. And the history recorded in the annals is just as sad ancient dessert wine as the history of the entire Ukrainian nation: “perestroika”, a row of economic crises, criminalization of the alcohol sector. page 32 The last straw was the occupation of Crimea by Russia and the loss of production sites and unique vineyards, including autochthonous varieties. Nevertheless, the industry is alive. It produces millions of decalitres, and even showed a Steven revival in the last year. At least on a moral level t. Spurrier: Continued on page 9 “The real Judgement of Paris movie was never made” page 21 2 rinks Dclock By the glass O Azerbaijan Wines from decline to a revival The production of Azerbaijani winemakers may be compared to the Phoenix bird. Just like this mythological creature, in the 21st century, Azerbaijani wine begins to revive after almost a complete decline in the 90s, when over 130 thousand hectares of vineyards were cut out in the country not only with technical varieties but which also opens up an incredibly also with unique table varieties. vast field of activity for crossing the As a new century set in, they Pan-Caucasian and local variet- managed to breathe a new life ies. -

Environment & Resource Efficiency

Environment & Resource Efficiency LIFE PROJECTS 2014 LIFE Environment Environment EUROPEAN COMMISSION ENVIRONMENT DIRECTORATE-GENERAL LIFE (“The Financial Instrument for the Environment and Climate Action”) is a programme launched by the European Commission and coordinated by the Environmen t and Climate Action Directorates-General . The Commission has delegated the implementation of many components of the LIFE programme to the Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (EASME). The contents of the publication “Environment & Resource Efficiency LIFE Projects 2014” do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions of the European Union. HOW TO OBTAIN EU PUBLICATIONS Free publications: • via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu); • at the European Commission’s representations or delegations. You can obtain their contact details on the Internet (http://ec.europa.eu) or by sending a fax to +352 2929-42758. Priced publications: • via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu). Priced subscriptions (e.g. annual series of the Official Journal of the European Union and reports of cases before the Court of Justice of the European Union): • via one of the sales agents of the Publications Office of the European Union (http://publications.europa.eu/others/ agents/index_en.htm). Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2015 ISBN 978-92-79-47116-2 ISSN 1977-2319 doi:10.2779/01257 © European Union, 2015 Reuse authorised. -

Indian Wine Industry Proposes New Standards India

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 4/17/2013 GAIN Report Number: IN3041 India Post: New Delhi Indian Wine Industry Proposes New Standards Report Categories: Agriculture in the Economy Wine Beverages Agriculture in the News Promotion Opportunities Approved By: David Williams Prepared By: D. Williams Report Highlights: The Indian Grape Processing Board has published draft standards for wine. For the most part, the standards reflect the guidelines of the International Organization of Vine and Wine. However, some standards have been modified to reflect existing Government of India standards. Disclaimer: This summary is based on a cursory review of the subject announcement and therefore should not be viewed under any circumstance, as a definitive reading of the regulation in question, or of its implications for U.S. agricultural export trade interests. Wine Industry Proposes New Standards India, through a request from the Ministry of Food Processing, joined the International Organization of Vine and Wine (known as OIV via its French acronym) on July 12, 2011. The Indian Grape Processing Board, which is a board comprised of representatives from the public and private sectors and established under the auspices of the Ministry of Food Processing, is now working to harmonize Indian wine standards with OIV guidelines and has published a solicitation of comments concerning the proposed standards. India does not currently have a set of wine production standards. Industry sources indicate that, for the most part, the proposed standards have been lifted directly from OIV guidelines. -

Wine & Spirits

Wine & Spirits Pasion & Traditë SPIRITS Historiku Background Kantina e Pijeve “Gjergj Kastrioti Skenderbeu” eshte kantina me e madhe The winery “ Gjergj Kastrioti Skenderbeu “ is the biggest winery in ne vend. Ndodhet ne Kodren e Rrashbullit dhe shtrihet ne nje siperfaqe the country. Is situated on the hill of Rrashbull and lies in an area of afro 45,000 m2. approximately 45,000 m2. Fillimet e saj jane ne vitin 1933, ku u krijua nga nje familje italiane ne Its beginnings were in 1933, which was created by an Italian family Sukth, ku behej perpunimi i thjeshte i rrushit me kapacatitete modeste in Sukth, in which was done simple processing of grapes in modest capacity. Ne vitin 1957 filloi ndertimi i Kantines ne kodren e Rrashbullit. In 1957 began the construction of the winery in Rrashbull hill. Kantina mori nje dimension te ri ne vitin 1960, kohe ne te cilen perfunduan The winery took a new dimension in 1960, at which time were completed 3 godinat e para, ku u rriten kapacatitet prodhuese. the three first buildings, and the production capacity increased. Puna voluminoze e ndertimit vazhdoi deri ne vitin 1987, duke e shnderruar Voluminous work of building went up in 1987, becoming this winery, the kete kantine ne kantinen me te madhe ne vend.. the largest winery in the country . Prodhimet e Kantines ishin Vera, Konjaku, Ferneti, Rakia dhe pije te The winery products were wine, brandy, fernet (tonic alcoholic drink with tjera. a little bitter taste), raki and other drinks. Produktet e Kantines jane vleresuar disa here me çmime ne konkurset Te winery products are evaluated several times with awards in national kombetare dhe nderkombetare. -

Cuisine Menu

• MENU • We are glad to welcome You at WHISKY CORNER! Our Scottish House is much more than just a restaurant. It is a place where friends, like-minded persons and people of good taste meet. At WHISKY CORNER, we have built for You the largest whisky collection in Eastern Europe: over 900 specimens from Scotland, Ireland, USA, Japan, Taiwan, India... As well as our own exclusive whisky releases, which are available only at our restaurant and at international festivals. WHISKY CORNER is the headquarters of Ukrainian Whisky Connoisseurs Club named after Aleksey Yakovlevich Savchenko. Thanks to this outstanding man Ukraine fell in love with whisky culture, learned the traditions and nuances of its production. Our restaurant also appeared as the result of his initiative. He inspired us with the dream of our own house for the Club — the Scottish House, where it will be so nice to taste whisky, discover new culinary pleasures, listen to a piper, enjoy the spirit of Scotland, and just to have a good time with friends. We made the dream come true! Nowadays, the ideas of the Whisky Club and the Scottish House are being kept and developed by the founder's son Aleksey Alekseevich Savchenko and his wife Irina Anatolyevna, as well as the members of the Club and the entire WHISKY CORNER team. Being in love with whisky — this noble, multifaceted drink — we have created a fine gastronomic accompaniment for it. In our menu, You will find Scottish specialties, European classics, and creative dishes. A duet of great whiskies and delicious, well-balanced meals makes the art of perfect dinning! 2 WHISKY RELEASES CRAFTED BY WHISKY CORNER Aleksey Yakovlevich Savchenko had one more dream of creating his own whisky. -

An Overview: Recent Research and Market Trends of Indian Wine Industry

Open Access Review Article J Food Processing & Beverages October 2015 Vol.:3, Issue:1 © All rights are reserved by Bheemathati Journal of Food Processing & An Overview: Recent Research Beverages and Market Trends of Indian Sarovar Bheemathati* Department of Virology, S.V. University, Tirupati-517 502, Andhra Wine Industry Pradesh, India *Address for Correspondence Sarovar Bheemathati, Department of Virology, S V University, Keywords: Research; Viticulture; Wine market; India Tirupati-517 502, Andhra Pradesh, India, Tel: (+91) 8801747541; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Submission: 24 August 2015 The wine industry related to flavor science is one of the most Accepted: 24 September 2015 globalized industries in the world. Even though wine was mentioned Published: 01 October 2015 as Somras or Madira in Indian mythology it has been viewed as a European product. Despite several socio economic constraints, the Copyright: © 2015 Bheemathati S. This is an open access article Indian wine market has already tasted its share of recognition in the distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which global market over the past few years. The increasing annual growth permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, at 25-30% and the lower per capita wine consumption indicate provided the original work is properly cited. immense potentiality of the untapped Indian wine market. The wine Reviewed and approved by: Dr. Andrew Reynolds, Professor of market depends on the wine production, consumption, imports and Viticulture, Brock University, Canada exports. This paper presents an overview of the research contributions and market trends of Indian wine industry. The contributions in the field of viticulture have been utilized by the industry and have led to the progressive economic growth of India. -

Working Wine Inventory

Dessert Wine Dessert Wine bottles are 375ml unless noted 1.5 3oz Btl bottles are 375ml unless noted 1.5 3oz Btl Sherry Sherry Lustau Puerto Fino (dry) Solera Reserva (750ml) 8 55 Lustau Puerto Fino (dry) Solera Reserva (750ml) 8 55 Lustau Rare Cream (sweet) Solera Superior (750ml) 9 60 Lustau Rare Cream (sweet) Solera Superior (750ml) 9 60 Alvear PX 'De Anada' 2011 23 46 175 Alvear PX 'De Anada' 2011 23 46 175 Madeira Madeira Miles Rainwater medium-dry 8 Miles Rainwater medium-dry 8 Broadbent 'Reserve' 5yr 10 Broadbent 'Reserve' 5yr 10 D'Oliveiras Bual 1908 100 200 D'Oliveiras Bual 1908 100 200 D'Oliveiras Bual 1982 30 60 D'Oliveiras Bual 1982 30 60 Port all Port bottles are 750ml unless noted Port all Port bottles are 750ml unless noted Fonseca 'Bin 27' Ruby (375ml) 7 Fonseca 'Bin 27' Ruby (375ml) 7 Taylor Fladgate 10yr Tawny 9 69 Taylor Fladgate 10yr Tawny 9 69 Taylor Fladgate 20yr Tawny 16 120 Taylor Fladgate 20yr Tawny 16 120 Taylor Fladgate 30yr Tawny 13 26 195 Taylor Fladgate 30yr Tawny 13 26 195 Taylor Fladgate 40yr Tawny 18 36 275 Taylor Fladgate 40yr Tawny 18 36 275 Dow's 2007 LBV (375ml) 55 Dow's 2007 LBV (375ml) 55 Warres 1980 Vintage Porto 225 Warres 1980 Vintage Porto 225 Warres 1994 Vintage Porto 165 Warres 1994 Vintage Porto 165 Williams Selyem San Benito County, CA 2011 135 Williams Selyem San Benito County, CA 2011 135 Riesling Riesling Poets Leap 'Botrytis' Columbia Valley, WA 2005 125 Poets Leap 'Botrytis' Columbia Valley, WA 2005 125 Poets Leap 'Botrytis' Columbia Valley, WA 2010 96 Poets Leap 'Botrytis' Columbia Valley, -

Forbidden Fruits: the Fabulous Destiny of Noah, Othello, Isabelle, Jacquez, Clinton and Herbemont ARCHE NOAH, Brussels and Vienna, April 2016

Forbidden Fruits: The fabulous destiny of Noah, Othello, Isabelle, Jacquez, Clinton and Herbemont ARCHE NOAH, Brussels and Vienna, April 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Noah, Othello, Isabelle, Jacquez, Clinton and Herbemont are six of the wine grape varieties whose turbulent history in Europe begins with the invasion of the vermin Phylloxera (Viteus vitifoliae) in the 19th century. Because of their natural resistance to Phylloxera, these varieties from North American breeders or from spontaneous crosses, were imported, amongst others, and used to counter the plague. Common strategies were to use breeds based on North American species as rootstocks to which European Vitis vinifera varieties were grafted, as well as to use them in longer term resistance breeding programs, primarily to infuse their resistance into Vitis vinifera. These varieties were, however, also directly planted in winegrowers’ fields. This particular practice gave them the name “direct producers” or “direct producer wines”. The term came to cover native American species as such (Vitis aestivalis, V. labrusca, V. riparia, V. rupestris), but also the first generation hybrids obtained from interspecific crossings, either with each other, or with the European common species Vitis vinifera, all the while maintaining their resistance to Phylloxera. Today, direct producer varieties are grown in several European countries, and wine is still produced from their harvest. Strangely though, the planting of some of them for the purpose of wine production is forbidden. Indeed, in the course of the direct producer’s 150-year history in Europe, first national, and then European laws have adopted a dramatically restrictive and unfairly discriminatory approach to certain direct producers and to hybrids, beginning mostly from the 1930s.