The Prevalence of Refractive Error in Three Com- Munities of Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cape Town VITO Pilot Studies Protocol

Open Access Protocol BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016485 on 22 December 2017. Downloaded from Rationale and design of the violence, injury and trauma observatory (VITO): the Cape Town VITO pilot studies protocol Ardil Jabar,1 Tolu Oni,1 Mark E Engel,2 Nemanja Cvetkovic,3 Richard Matzopoulos1 To cite: Jabar A, Oni T, ABSTRACT Engel ME, et al. Rationale Strengths and limitations of this study and design of the violence, INTRODUCTION injury and trauma observatory The establishment of violence and injury observatories ► The observatories model is an internationally (VITO): the Cape Town VITO pilot elsewhere has been found to reduce the burden within accepted tool that can provide a focused studies protocol. BMJ Open a relatively short period. Currently no integrated system understanding of a particular issue or subtheme of 2017;7:e016485. doi:10.1136/ exists in South Africa to provide collated data on violence, violence. bmjopen-2017-016485 to allow for targeted interventions and routine monitoring ► The integration of violence and injury data may ► Prepublication history for and evaluation.This research seeks to identify if bringing allow a comprehensive view of the existing burden this paper is available online. multiple data sources, including but not limited to data of violence and injury within a community. To view these files please visit from the South African Police Service (SAPS), Forensic ► A potential limitation of certain datasets, for example, the journal online (http:// dx. doi. Pathology Services (FPS), Emergency Medical Services Health Systems Trust (HST), are their periodical org/ 10. 1136/ bmjopen- 2017- (EMS) and local hospital clinical databases, together are (1) survey collection, that is, biannual, not continuous, 016485). -

Clinics in City of Cape Town

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza City of Cape Town Metro Health facilities Eastern Sub District , Area East, KESS Clinic Name Physical Address Contact Number City Ikhwezi CDC Simon Street, Lwandle, 7140 021 444 4748/49/ Siyenza 51/47 City Dr Ivan Toms O Nqubelani Street, Mfuleni, Cape Town, 021 400 3600 Siyenza CDC 7100 Metro Mfuleni CDC Church Street, Mfuleni 021 350 0801/2 Siyenza Metro Helderberg c/o Lourensford and Hospital Roads, 021 850 4700/4/5 Hospital Somerset West, 7130 City Eerste River Humbolt Avenue, Perm Gardens, Eerste 021 902 8000 Hospital River, 7100 Metro Nomzamo CDC Cnr Solomon & Nombula Street, 074 199 8834 Nomzamo, 7140 Metro Kleinvlei CDC Corner Melkbos & Albert Philander Street, 021 904 3421/4410 Phuthuma Kleinvlei, 7100 City Wesbank Clinic Silversands Main Street Cape Town 7100 021 400 5271/3/4 Metro Gustrouw CDC Hassan Khan Avenue, Strand 021 845 8384/8409 City Eerste River Clinic Corner Bobs Way & Beverly Street, Eeste 021 444 7144 River, 7100 Metro Macassar CDC c/o Hospital -

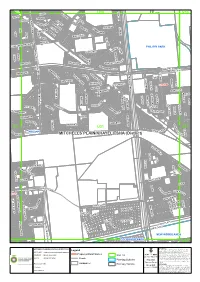

Mitchell's Plain Nodal Economic Development Profile

Mitchell’s Plain Nodal Economic Development Profile Western Cape Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction............................................................................................3 Section 2: An Overview of Mitchell’s Plain .............................................................4 Section 3: The Economy of Mitchell’s Plain............................................................7 Section 4: Enabling Environment ...........................................................................9 Section 5: Economic Growth and Investment Opportunities ................................10 Section 6: Summary.............................................................................................14 2 Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Purpose The intention of this paper is to serve as a succinct narrative report on the Mitchell's Plain Nodal Economic Development Profile.1 The profile report is structured to give digestible, user-friendly and easily readable pieces of information on the economic character of the Mitchell's Plain Integrated Sustainable Urban Development (UDP) node. 1.2 The nodal economic profiling initiative In August 2005, in a meeting with the Urban and Rural Development (URD) Branch,2 the minister of Provincial and Local Government raised the importance of the dplg programmes playing a crucial role in contributing to the new economic growth targets as set out in the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa (ASGISA). He indicated the need to develop an economic development programme of action -

MITCHELLS PLAIN/KHAYELITSHA (District) HT

TSHITSHI T30 DUBU DLEPHU U30 V30 TALENI KOBODI AMSTERDAM MGWALI O N DYUSHU L J M I NQA A MANZANA BA R H COLOSA DEBEZA SANGXA DIYA SIPHINGO HO SI B CIKO B E MENDU O MZAZI MBEM Q HOB O H O BUHLUNGU T LO RHA S H A BRISTOL B O MLAMBALALENI TYHALI PHILIPPI PARK UNZ INGULUBE H P A M N SAGOLODA NOMYAYI E GXAKA DWEZA D Y W A B A SI U T H SIKHWENENE N AYI VUKU EMAZIZINI GWILI OMY INGLUBE GW A NGQ A MG HA SHEFFIELD SAK H VIETNAM SHEFFIELD W S MBOMVANE A IK T D NEW EISLEBEN S Y NY A H H A T W A K H EIGHTEEN A AL TWO ROAD 34 L I M A A ROAD 33 S ONE NZINZINIBA H N E Z NTSIKISI I HLUNGULU FOUR ZERO ROAD BHONKEQUMBU A M BHONKE ROAD FIVE ROAD SIX U MTHOMBE SEVENTEEN SIXTEEN Q VEN NINETEEN SE TWENTY N MNYAMANZI M EIGHT N O N O G K INGULUBE X THIRTEEN SAGWITYI NTSINDE N W KW KHAM A TEN TWELVE ELEVEN MDLAMBI E E FIFTEEN L PI M A LE PA T NT N W AMB G E NTY ONE SIX ANANE E LE GXIYA NQWEBEBA CHAWUZE NOQWA TH NABILEYO T A NOWANGA W NOMAWENI E N T31 U31 V31THIRTY T E Y M TWEN FIV H PHILIPPI T Y E LO IG NTLO MITCHELLS PLAIN/KHAYELITSHA (District) HT LE EU BE KK STORK I E LILY PETUNIA ANGELIER MERIGOLD RD RADU A H N A O GALAWENI R S R E A T Y L E GW R ALA FENQE HEINZ PARK ROOS DAISY N OLIVER T TAM Y BO A DISA P T O LAC Y AMB E STOFILE STREET S H O LILLIAN NGOYI B A SUNFLOWER DAHLIA A B GOEIEHOOP S A H D ORCHID O DUMA NOKWE N MAKARENA B S WHITE HART A LE N CHAR PROTEA E GOODISON LOFTUS ANFIELD K R FEROZAADAM LLA PA HIGHFIELD VI ELLANDF IL WELTEVREDEN B TROJAN HORSE E CAPE FLATS R T CAPE FLATS NEW WOODLANDS T32 U32 COLORADO PARK V32 COPYRIGHT: MITCHELLS PLAIN/KHAYELITSHA DISTRICT U31 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. -

Khayelitsha Western Cape Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & Dplg, 2007 Khayelitsha Context

Nodal Economic Profiling Project Khayelitsha Western Cape Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & dplg, 2007 Khayelitsha Context IInn 22000011,, SSttaattee PPrreessiiddeenntt TThhaabboo MMbbeekkii aannnnoouunncceedd aann iinniittiiaattiivvee ttoo aaddddrreessss uunnddeerrddeevveellooppmmeenntt iinn tthhee mmoosstt sseevveerreellyy iimmppoovveerriisshheedd aarreeaass rruurraall aanndd uurrbbaann aarreeaass ((““ppoovveerrttyy nnooddeess””)),, wwhhiicchh hhoouussee aarroouunndd tteenn mmiilllliioonn ppeeooppllee.. TThhee UUrrbbaann RReenneewwaall PPrrooggrraammmmee ((uurrpp)) aanndd tthhee IInntteeggrraatteedd SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee RRuurraall Maruleng DDeevveellooppmmeenntt PPrrooggrraammmmee Sekhukhune ((iissrrddpp)) wweerree ccrreeaatteedd iinn 22000011 Bushbuckridge ttoo aaddddrreessss ddeevveellooppmmeenntt iinn Alexandra tthheessee aarreeaass.. TThheessee iinniittiiaattiivveess Kgalagadi Umkhanyakude aarree hhoouusseedd iinn tthhee DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff PPrroovviinncciiaall aanndd Zululand LLooccaall GGoovveerrnnmmeenntt ((ddppllgg)).. Maluti-a-Phofung Umzinyathi Galeshewe Umzimkhulu I-N-K Alfred Nzo Ukhahlamba Ugu Central Karoo OR Tambo Chris Hani Mitchell’s Plain Mdantsane Khayelitsha Motherwell UUP-WRD-Khayelitsha Profile-301106-IS 2 Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & dplg, 2007 Khayelitsha Khayelitsha poverty node z Research process Activities Documents z Overview People z Themes – Residential life – Commercial activity – City linkages z Summary z Appendix UUP-WRD-Khayelitsha Profile-301106-IS 3 Nodal -

Khayelitsha Through Cycling

DURBANVILLE Northern Suburbs PLATTEKLOOF EDGEMEAD MILNERTON TYGER VALLEY BRACKENFELL GREEN POINT BELLVILLE SEA POINT SALT RIVER City Centre 04 VELOKHAYA LIFE CYCLING ACADEMY TREVOR STELLENBOSCH VICTORIA VILLAGE N2 CAMPS BAY Adventure & Activities VILAKAZI TABLE MOUNTAIN MERGE 14 3 NORTH CLAREMONT GUGULETU Atlantic Seaboard Velokhaya is a non-governmental organization (NGO) that’s changing the lives KENILWORTH VILLAGE of the youth of Khayelitsha through cycling. Take a tour of their brightly coloured LLANDUDNO Southern Suburbs Curated by Buntu Matole CONSTANTIA Cape Flats KHAYELITSHA site and hear their story of how they have trained and nurtured kids in the neigh- 4 NORTH KHAYELITSHA Buntu has lived most of his life in Khayelitsha and HOUT BAY MACASSAR bourhood to become biking and BMX champions competing at professional level TABLE MOUNTAIN STRANDFONTEIN through his love and passion for sport has travelled NATIONAL PARK (SILVERMINE) LAVENDER HILL countrywide representing his school, community at international events. PAMA RD SOMERSET WEST club and the province to promote positive change MUIZENBERG Helderberg PAMA RD M32 for his community. STRAND 20 SOLOMON FISH HOEK GORDON’S BAY MAHLANGU False Bay SIMON’S TOWN 01 DISCOVERIKASI 04 SCARBOROUGH N 401 Makabeni Street, Khayelitsha, 7784 11 M45 VILLAGE Peninsula EFT, debit and credit cards and cash. DiscoverIkasi is a booking engine that helps visitors to townships around South 16:00 to 18:00 – Seven days a week 23 2 NORTH Africa find accommodation, restaurants, and tours. The platform will help you Shaun Doch C +27 (0) 64 035 1715 22 KHAYELITSHA N 24 VILLAGE 15 book your complete experience, from luxurious B&Bs to bustling backpackers, E [email protected] 12 as well as various dining experiences and a wide array of township activities. -

Cape High Court, Cape Town)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA (Cape High Court, Cape Town) Case No. 21600/12 In the matter between: MINISTER OF POLICE First Applicant NATIONAL COMMISSIONER OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE Second Applicant THE PROVINCIAL COMMISSIONER OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE FOR THE WESTERN CAPE Third Applicant THE CIVILAN SECRETARIAT FOR THE POLICE SERVICE Fourth Applicant COLONEL M F REITZ Fifth Applicant BRIGADIER Z DLADLA Sixth Applicant COLONEL T RABOLIBA Seventh Applicant and THE PREMIER OF THE WESTERN CAPE First Respondent THE MEMBER OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL FOR COMMUNITY SAFETY, WESTERN CAPE Second Respondent THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN Third Respondent THE HON. JUSTICE C O'REGAN N.O. Fourth Respondent ADVVPPIKOLI N.O. Fifth Respondent THE SECRETARY TO THE COMMISSION Sixth Respondent 2 ADV T SIDAKI Seventh Respondent WOMEN'S LEGAL CENTRE Eighth Respondent THE SOCIAL JUSTICE COALITION Ninth Respondent SUPPORTING AFFIDAVIT I the undersigned ABDURRAZACK ("ZACKIE") ACHMAT hereby affirm and say 1. I am an adult male resident at A536 St. Martini Garden, Queen Victoria Street, Cape Town. I am fifty years old. 2. The facts contained herein are true and correct and are within my personal knowledge unless the context indicates otherwise. 3. I have been a political activist since the age of 14. I was a co-founder and Director of the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality, Director of the AIDS Law Project, and a co-founder and chairperson of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC). I have been co-opted to Equal Education's (EE) National Council. EE is an organisation dedicated to realising the right to decent, quality education for all. -

The Making and Re-Imagining of Khayelitsha

The Making and Re-imagining of Khayelitsha Josette Cole Executive Director, Development Action Group (DAG) and Research Associate, Centre for Archive and Public Culture, University of Cape Town Report for the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Police Inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a Breakdown in Relations between the Community and the Police in Khayelitsha January 2013 PREFACE During a working career that now spans 37 years I have worked in a number of institutions – i.e. VERITAS, the Surplus People’s Project, W. Cape (SPP), the MANDLOVU Development Initiative and, the Development Action Group (DAG). In all of these I have both honed and applied incremental skills learnt from direct practice to design and implement programmes and projects related to urban land, housing, local government, community development and, capacity building in the context of a pro-poor agenda. Between 1996 and 2012 I also worked as a freelance development consultant and researcher through my small company, Social Trends Development Services, where I worked on numerous assignments for government, the NGO sector, and international NGOs related to the design and evaluation of a range of programmes and projects linked to reconstruction and development in the context of our democratic transition. In between my professional work I have researched, written and published numerous articles, academic papers and books, three of the latter extensively cover various aspects of Cape Town’s social history, with a special focus on past and present settlement life in the South-east Metro of the city. I am a Research Associate in the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative based in the Social Anthropology Department at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and about to formally register as a PhD candidate in Historical Studies at UCT. -

Informal Settlement Upgrading Programme: Monwabisi Park, Cape Town Ecovillage Development and Collaborative Learning Why Monwabisi Park?

Informal Settlement Upgrading Programme: Monwabisi Park, Cape Town Ecovillage Development and Collaborative Learning Why Monwabisi Park? Monwabisi Park (MWP) is a squatter settlement of some 5,500 households located along the southern boundary of Khayelitsha, Cape Town’s largest township. It was formed in 1997, when people began to build shacks on an adjacent, unoccupied nature reserve. Some 20,000 people, the majority from the Eastern Cape, now live in MWP. While only 20 kilometers from the central business district of Cape Town, most MWP residents have yet to find an economic foothold. The unemployment rate in MWP is about 50% and some 80% of households that do not have some form of in- come (wages, social grants, informal trading) earn less than the minimum monthly subsistence level of R1900 ($200). The Indlovu Project began in 2005 when Di Womersley of the Shaster Foundation joined forces with Buyiswa Tonono, a local street committee leader and Monwabisi Park founder of a small crèche that became the first Indlovu Centre building. The crèche and subsequent Montessori Preschool cared for young children, including AIDS or- phans. As a community-driven effort to address local needs, the project sponsored a soup kitchen, a health clinic, community gardens, and built a youth centre and a guest house, using a unique “Ecobeam” frame and sandbag construction technique. In 2007, Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) an American technical university, began working with the Indlovu project on redevelopment planning initiatives. WPI is helping to refine the project’s broad permacul- ture inspired strategy to address critical issues associ- ated with community upgrading. -

Sybrand Park Neighbourhood

Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 Section 1: Description of the Sybrand Park neighbourhood ......................................................... 2 Section 2, part 1: Main Themes Emerging from Interviews Conducted in Sybrand Park ............ 4 Economic Issues and Changes .................................................................................................... 4 Change in economic activity .................................................................................................... 4 Services and Infrastructure Issues and Changes ........................................................................ 5 Drainage .................................................................................................................................. 5 Sewerage ................................................................................................................................. 5 Road maintenance and traffic congestion .............................................................................. 5 Transportation ......................................................................................................................... 5 Secondary Services .................................................................................................................. 6 Schools .................................................................................................................................... -

2016 Socio-Economic Profile: City of Cape Town

City of Cape Town 2016 At a Glance: City of Cape Town Community Survey, 2016 4 004 793 1 264 849 Matric Pass Rate 2015 83.6% Poverty headcount (2016) 2.6% Percentage households with no Literacy Rate 2011 90.5% income (2016) 13.9% 2015 158 93.3% 62.3 4.8% Percentage change between 2015 and 2016 in number of reported cases per 100 000 -3.3% -14.9% 4.7% -1.3% -0.4% Percentage change between 2015 and 2016 in number of households enjoying access 18.9% 10.2% 23.1% 22.2% GDP Growth Employment Growth 2005 – 2015 2005 – 2015 Wi-Fi hotspots will be installed in all of the 3.2% City’s 111 wards by 1 March 2018. 2.1% Contribution to GDP, 2015 Government and Community, Social and Commercial Services Manufacturing Personal Services 60.0% 17.7% 14.8% 1. DEMOGRAPHICS 4 2. EDUCATION 7 3. HEALTH 11 4. POVERTY 16 5. BASIC SERVICE DELIVERY 19 6. SAFETY AND SECURITY 23 7. THE ECONOMY 27 8. BROADBAND 33 SOURCES 35 3 2016 Socio-economic Profile: City of Cape Town 1 DEMOGRAPHICS Demographics is broadly defined as the study of population dynamics. It is significantly influenced by a wide array of factors such as birth and death rates, migration patterns, age, race, gender and life expectancy. The importance of understanding demographics as a decisive factor in shaping our current socio-economic reality is therefore critical for governments, economists and politicians alike. The following section provides a concise, yet meaningful overview of the most prominent demographic indicators relevant for municipal planning and budgeting. -

Prone Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa

Survey Methodology in Violence- prone Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa Ndodana Nleya and Lisa Thompson Abstract This article discusses the methodological challenges of a service delivery survey in Khayelitsha, a township in Cape Town, South Africa. The survey aimed to gain a better understanding of the relationship between citizen participation and the environmental challenges facing residents in this urban area. Khayelitsha is a township prone to violence. Encountering violence during fieldwork can alter the way researchers execute research, yet this often remains unacknowledged in ‘objective social science’, especially in probability sampling. The article examines the effects of the risk felt by researchers on the research method employed in quantitative surveys. It shows that deliberating on this aspect of the research process is both necessary and useful, especially in terms of recognising the need to factor fear or uncertainty into the ways in which research processes unfold. 1 Introduction This article examines the effects of subjectively This article presents an appraisal of felt risk on the research method employed in methodological challenges of a service delivery quantitative surveys. It shows that deliberating survey study in Khayelitsha, a township in Cape on this aspect of the research process is both Town, South Africa. The central goal of the necessary and useful, especially in terms of survey was to gain a better understanding of the recognising the need to factor fear or uncertainty connections between urban environmental into the ways in which the research process challenges facing residents in the area and unfolds, especially in the contexts of poor and citizen participation methods.