A Study of Resettled Tribes at Aralam, Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 19.04.2020To25.04.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 19.04.2020to25.04.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Police Sl. No. father of which Time of Officer, at which Accused Sex Accused Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 560/2020 U/s 269,271,188 IPC & Sec ZHATTIYAL 118(e) of KP Balakrishnan NOTICE HOUSE, Chirakkal 25-04- Act &4(2)(f) VALAPATTA 19, Si of Police SERVED - J 1 Risan k RASAQUE CHIRAkkal Amsom 2020 at r/w Sec 5 of NAM Male Valapattanam F C M - II, amsom,kollarathin Puthiyatheru 12:45 Hrs Kerala (KANNUR) P S KANNUR gal Epidermis Decease Audinance 2020 267/2020 U/s KRISNA KRIPA NOTICE NEW MAHE 25-04- 270,188 IPC & RATHEESH J RAJATH NALAKATH 23, HOUSE,Nr. New Mahe SERVED - J 2 AMSOM MAHE 2020 at 118(e) of KP .S, SI OF VEERAMANI, VEERAMANI Male HEALTH CENTER, (KANNUR) F C M, PALAM 19:45 Hrs Act & 5 r/w of POLICE, PUNNOL THALASSERY KEDO 163/2020 U/s U/S 188, 269 Ipc, 118(e) of Kunnath house, kp act & sec 5 NOTICE 25-04- Abdhul 28, aAyyappankavu, r/w 4 of ARALAM SERVED - J 3 Abdulla k Aralam town 2020 at Sudheer k Rashhed Male Muzhakunnu kerala (KANNUR) F C M, 19:25 Hrs Amsom epidemic MATTANNUR diseases ordinance 2020 149/2020 U/s 188,269 NOTICE Pathiriyad 25-04- 19, Raji Nivas,Pinarayi IPC,118(e) of Pinarayi Vinod Kumar.P SERVED - A 4 Sajid.K Basheer amsom, 2020 at Male amsom Pinarayi KP Act & 4(2) (KANNUR) C ,SI of Police C J M, Mambaram 18:40 Hrs (f) r/w 5 of THALASSERY KEDO 2020 317/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC & 118(e) of KP Act & Sec. -

Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala Breeding of Black-Winged

Vol.14 (1-3) Jan-Dec. 2016 newsletter of malabar natural history society Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife Breeding of in two decades Black-winged Patterns of Stilt Discovery of at Munderi Birds in Kerala Kadavu European Bee-eater Odonates from Thrissur of Kadavoor village District, Kerala Common Pochard Fulvous Whistling Duck A new duck species - An addition to the in Kerala Bird list of - Kerala for subscription scan this qr code Contents Vol.14 (1-3)Jan-Dec. 2016 Executive Committee Patterns of Discovery of Birds in Kerala ................................................... 6 President Mr. Sathyan Meppayur From the Field .......................................................................................................... 13 Secretary Akkulam Lake: Changes in the birdlife in two decades ..................... 14 Dr. Muhamed Jafer Palot A Checklist of Odonates of Kadavoor village, Vice President Mr. S. Arjun Ernakulam district, Kerala................................................................................ 21 Jt. Secretary Breeding of Black-winged Stilt At Munderi Kadavu, Mr. K.G. Bimalnath Kattampally Wetlands, Kannur ...................................................................... 23 Treasurer Common Pochard/ Aythya ferina Dr. Muhamed Rafeek A.P. M. A new duck species in Kerala .......................................................................... 25 Members Eurasian Coot / Fulica atra Dr.T.N. Vijayakumar affected by progressive greying ..................................................................... 27 -

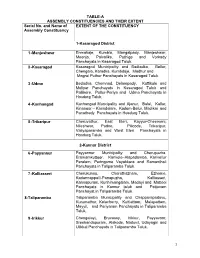

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

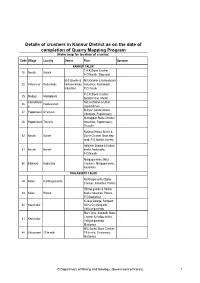

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: a Study on Aralam Farm

Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A study on Aralam Farm A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology by Deepa Sebastian (Reg. No.1434502) Under the Guidance of Sudhansubala Sahu Assistant Professor Department of Sociology CHRIST UNIVERSITY BENGALURU, INDIA December 2016 APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Dissertation entitled ‘Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A Study on Aralam Farm’ b y Deepa Sebastian Reg. No. 1434502 is approved for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology. Examiners: 1. 2. Supervisor: ___________________ ___________________ Chairman: ___________________ ___________________ Date: Place: Bengaluru ii DECLARATION I Deepa Sebastian hereby declare that the dissertation, titled ‘Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A Study on Aralam Farm’ is a record of original research work undertaken by me for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sociology. I have completed this study under the supervision of Dr Sudhansubala Sahu, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology. I also declare that this dissertation has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other title. It has not been sent for any publication or presentation purpose. I hereby confirm the originality of the work and that there is no plagiarism in any part of the dissertation. Place: Bengaluru Date: Deepa Sebastian Reg. No.1434502 Department of Sociology Christ University, Bengaluru iii CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation submitted by Deepa Sebastian (1434502 ) titl ed ‘Impact of Resettlement on Scheduled Tribes in Kerala: A Study on Aralam Farm’ is a record of research work done by her during the academic year 2014-2016 under my supervision in partial fulfillment for the award of Master of Philosophy in Sociology. -

Preliminary Pages.Qxd

State Formation and Radical Democracy in India State Formation and Radical Democracy in India analyses one of the most important cases of developmental change in the twentieth century, namely, Kerala in southern India, and asks whether insurgency among the marginalized poor can use formal representative democracy to create better life chances. Going back to pre-independence, colonial India, Manali Desai takes a long historical view of Kerala and compares it with the state of West Bengal, which like Kerala has been ruled by leftists but has not experienced the same degree of success in raising equal access to welfare, literacy and basic subsistence. This comparison brings historical state legacies, as well as the role of left party formation and its mode of insertion in civil society to the fore, raising the question of what kinds of parties can effect the most substantive anti-poverty reforms within a vibrant democracy. This book offers a new, historically based explanation for Kerala’s post- independence political and economic direction, drawing on several comparative cases to formulate a substantive theory as to why Kerala has succeeded in spite of the widespread assumption that the Indian state has largely failed. Drawing conclusions that offer a divergence from the prevalent wisdoms in the field, this book will appeal to a wide audience of historians and political scientists, as well as non-governmental activists, policy-makers, and those interested in Asian politics and history. Manali Desai is Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Kent, UK. Asia’s Transformations Edited by Mark Selden Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The books in this series explore the political, social, economic and cultural consequences of Asia’s transformations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

Date of Publication of Tender / Bids

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA LOCAL SELF GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT Office of the Assistant Executive Engineer,LSGD Sub Division, Iritty Block Panchayath e-Tender No: D/TNR/3/2016-17 Dated 17/11/2016 e-Government Procurement (e-GP) NOTICE INVITING TENDER The Assistant Executive Engineer, LSGD Sub Division, Iritty Block Panchayath, LSG (EW) Department for and on behalf of the Governor of Kerala invites online bids from the registered bidders of PWD. Date of publication of Tender / Bids - 19/11/2016 11:00 AM Last date and time of Receipt of Tender / Bids - 26/11/2016 11:00 AM Date and Time of Opening of Tender - 29/11/2016 11:00 AM Sl. Name of Work PAC Estimate EMD Fee VAT Total Fee Period of Classification No. Amount including completion of Bidder VAT (in months) 1 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0018/17 - Tarring Works to 4,95,448 5,00,000 12,500 1,000 50 1,050 4 D Class and Ottakombanchal Kunnu Road in Pyam GP above 2 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0019/17 - Tarring Works to 4,94,038 5,00,000 12,500 1,000 50 1,050 4 D Class and Thazhekappil Karakkattu Junction Kochangadi Road km 0/065 to above 0/155 in Ayyankunnu GP 3 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0020/17 - Tarring Works to 8,99,546 9,00,000 22,500 1,800 90 1,890 4 D Class and Uruppumkutti Ezhamkadavu Road km 0/260 to 0/360 in above Ayyankunnu GP 4 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. S0021/17 - Tarring works to 7,96,213 8,00,000 20,000 1,600 80 1,680 4 D Class and Chedikkulam Pannimoola Road in Aralam GP above 5 Iritty Block Panchayath Project No. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 09.12.2018To15.12.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 09.12.2018to15.12.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kidinhiyil House, Cr No 682/18 Nelson 38/18 Chembilode 09.12.2018 Bailed by 1 Pramod.K Balan Nair Chirakkuthazhe, U/S 118 (a) of Edakkad Nicholause, SI ,Male amsom Chala at 18.05 hrs Police Thottada KP Act of Police Edakkad Cr No 683/18 Mahesh 19/18,M Nallamthottathil amsom Nr 09.12.2018 Bailed by 2 Vishnu.P Prasannan U/S 118 (a) of Edakkad Kandambeth ale House, Edakkad PO Mathrubhumi at 23.50 hrs Police KP Act ,SI Of Police Office Prakasan,SI of Thazheppurakkal(H),C 636/18U/s Ahammadkutt 60/18,m 2018-12- Sreekandapur Police,Sreekan Released on 3 Youseph hengalayi Amsom Kottoor 279IPC&185 of y ale 09T20:10 am dpauram bail; Cheramoola MV Act Police Station VijilNivas, 708/18 u/s 118( 29, Chakkarakkal 09 12 2018 Released on 4 Sherin Prakash Prakashan Uchulikunnummal, e) of KP Act & Chakkarakkal Babumon SI Male Town at 0030 hrs bail Mamba 185 of MV Act 09 12 2018 709/18 u/s 118( 57, Koyodan House, Released on 5 Pavithran K Sankaran Kanhirode at e) of KP Act & Chakkarakkal Babumon SI Male Koodali Mandapam bail 1100 hrs 185 of MV Act 710/18 u/s 118( 23, Thattantevalappil(H), 09 12 2018 e) of KP Act & Released on 6 Shijil KC Rajan Sona Road Chakkarakkal Babumon SI Male Kannadivelicham at 1730 -

Kerala – CPI-M – BJP – Communal Violence – Internal Relocation

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND34462 Country: India Date: 25 March 2009 Keywords: India – Kerala – CPI-M – BJP – Communal violence – Internal relocation This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide brief information on the nature of the CPI-M and the BJP as political parties and the relationship between the two in Kerala state. 2. Are there any reports of Muslim communities attacking Hindu communities in Kerala in the months which followed the 1992 demolition of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya? If so, do the reports mention whether the CPI-M supported or failed to prevent these Muslim attacks? Do any such reports specifically mention incidents in Kannur, Kerala? 3. With a view to addressing relocation issues: are there areas of India where the BJP hold power and where the CPI-M is relatively marginal? 4. Please provide any sources that substantiate the claim that fraudulent medical documents are readily available in India. RESPONSE 1. Please provide brief information on the nature of the CPI-M and the BJP as political parties and the relationship between the two in Kerala state. -

Report of Rapid Impact Assessment of Flood/ Landslides on Biodiversity Focus on Community Perspectives of the Affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems

IMPACT OF FLOOD/ LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES AUGUST 2018 KERALA state BIODIVERSITY board 1 IMPACT OF FLOOD/LANDSLIDES ON BIODIVERSITY - COMMUnity Perspectives August 2018 Editor in Chief Dr S.C. Joshi IFS (Retd) Chairman, Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram Editorial team Dr. V. Balakrishnan Member Secretary, Kerala State Biodiversity Board Dr. Preetha N. Mrs. Mithrambika N. B. Dr. Baiju Lal B. Dr .Pradeep S. Dr . Suresh T. Mrs. Sunitha Menon Typography : Mrs. Ajmi U.R. Design: Shinelal Published by Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram 2 FOREWORD Kerala is the only state in India where Biodiversity Management Committees (BMC) has been constituted in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporation way back in 2012. The BMCs of Kerala has also been declared as Environmental watch groups by the Government of Kerala vide GO No 04/13/Envt dated 13.05.2013. In Kerala after the devastating natural disasters of August 2018 Post Disaster Needs Assessment ( PDNA) has been conducted officially by international organizations. The present report of Rapid Impact Assessment of flood/ landslides on Biodiversity focus on community perspectives of the affect on Biodiversity and Ecosystems. It is for the first time in India that such an assessment of impact of natural disasters on Biodiversity was conducted at LSG level and it is a collaborative effort of BMC and Kerala State Biodiversity Board (KSBB). More importantly each of the 187 BMCs who were involved had also outlined the major causes for such an impact as perceived by them and suggested strategies for biodiversity conservation at local level. Being a study conducted by local community all efforts has been made to incorporate practical approaches for prioritizing areas for biodiversity conservation which can be implemented at local level. -

Sumi Project

1 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................ 3-11 Chapter 1 Melting Jati Frontiers ................................................................ 12-25 Chapter 2 Enlightenment in Travancore ................................................... 26-45 Chapter 3 Emergence of Vernacular Press; A Motive Force to Social Changes .......................................... 46-61 Chapter 4 Role of Missionaries and the Growth of Western Education...................................................................... 62-71 Chapter 5 A Comparative Study of the Social Condions of the Kerala in the 19th Century with the Present Scenerio...................... 72-83 Conclusion ............................................................................................ 84-87 Bibliography .......................................................................................88-104 Glossary ............................................................................................105-106 2 3 THE SOCIAL CONDITIONS OF KERALA IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO TRAVANCORE PRINCELY STATE Introduction In the 19th century Kerala was not always what it is today. Kerala society was not based on the priciples of social freedom and equality. Kerala witnessed a cultural and ideological struggle against the hegemony of Brahmins. This struggle was due to structural changes in the society and the consequent emergence of a new class, the educated middle class .Although the upper caste -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur Rural District from 07.03.2021To13.03.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur Rural district from 07.03.2021to13.03.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 13-03-2021 48/2021 U/s 38, Aalunkal(h),Chunga Kelakam BAILED BY 1 VINOD SCARIYA chungakkunnu at 21:45 15(c) r/w 63 vipindas A Male kkunnu (KANNUR) POLICE Hrs of Abkari Act 13-03-2021 48/2021 U/s 24, Penthanathu(h),Pott Kelakam BAILED BY 2 Byju benny chungakkunnu at 21:45 15(c) r/w 63 vipindas A Male amthodu (KANNUR) POLICE Hrs of Abkari Act 13-03-2021 63/2021 U/s Narayanan 48, Puthiyaveedu,Thilla ARALAM Bailed by 3 Sathyan k Athikkal at 19:20 15(c) r/w 63 Prakasan K,SI Nambiar Male nkery po,Thillankery (KANNUR) Police Hrs of Abkari Act ALORA HOUSE, 13-03-2021 95/2021 U/s 28, Iritty Bailed by 4 NIKHIL A DIVAKARAN VALLIYAD, PAYAM IRITTY at 19:00 118(a) of KP AKHIL TK Male (KANNUR) Police AMSOM IRITTY Hrs Act 62/2021 U/s Thayyil 13-03-2021 20, 279IPC&sec. ARALAM Bailed by 5 Junaid TS Saleem house,Puthiyangadi, Keezpally at 17:50 Prakasan K,SI Male 132(1)r/w17 (KANNUR) Police Aralam amsom Hrs 9ofMV Act Kizhakkekara(H) 13-03-2021 94/2021 U/s 40, Alakode Bus ALACODE Ranjith M K, Si BAILED BY 6 Jomon K U Ulahannan Padankavala, at 17:10 15(c) r/w 63 Male stand (KANNUR) of Ploce POLICE Payyavoor Amsom Hrs of Abkari Act Edacheriyan House, 12-03-2021 81/2021 U/s Kunhiraman 33, Near Supplyco, Pariyaram Rathnakaran.E BAILED BY 7 Majesh.E Kappanathattu at 20:30 15(c) r/w 63 , Male Chudala, Pariyaram MC (KANNUR) , SI Of Police POLICE Hrs of Abkari Act Amsom Thekkan House, Kundamkuzhi, Near 12-03-2021 81/2021 U/s 50, Pariyaram Rathnakaran.E BAILED BY 8 Prakasan.T Pathrose Mariyapuram Kappanathattu at 20:30 15(c) r/w 63 Male MC (KANNUR) , SI Of Police POLICE Church, Ezhome Hrs of Abkari Act Amsom Kovval Valappil Pariyaram 12-03-2021 80/2021 U/s Narayanan.