Final Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

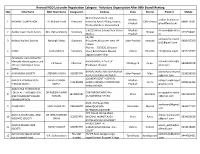

Revised NGO List Under Registration Category

Revised NGO List under Registration Category - Voluntary Organization After 80th Board Meeting SNo NGO Name NGO Head Name Designation Address State District Email id Mobile 48 Panchwati Ward, Opp. Madhya aadhar.foundation 1 AADHAR FOUNDATION ER. Mahesh Kinth President Narendra Ayush Dhaba, Poama, Chhindwara 8989173581 Pradesh @rediffmail.com P/o Kundali Kala, Parasia Road E-4/223,Arera Colony,Near 10 no. Madhya [email protected] 2 Aadhar Gyan Dhatri Samiti Mrs. Ratna Mukerji Secretary Bhopal 9755554401 Market Pradesh m S2/258 adityawelfaresocie 3 Aaditya Welfare Society Narsingh Yadav Secretary Bhojubeer,Bhojubeer,Near UP Uttar Pradesh Varanasi 9936437260 [email protected] College Plot No. - 70/3530, (Ground 4 AAINA Sneha Mishra Secretary Floor),Behind Hotel Mayfair Odisha Khordha [email protected] 9437017967 Lagoon,Jaydev Vihar Aakanksha Lions School for Mentally Handicapped a unit Awanti Vihar,,In front of aakankshalsmh@y 5 K K Nayak Chairman Chattisgarh Raipur 9826845678 of Lions Club Raipur Sewa Bhaktawar Bhawan ahoo.com Samiti KHARAGIPUR,GANGAUPUR,RAM akankshasocietyma 6 AAKANKSHA SOCIETY JITENDRA YADAV SECRETARY Uttar Pradesh Mau 9258038100 AUPUR SUWAH LINK MARG [email protected] 120 NEAR GOVT HOSPITAL AARIOLA PRAKASH PUNJ BALVEER SINGH Madhya balveer.singhrajput 7 CHAIRMAN HARDA,AWASTHI COMPOUND Harda 9009616393 SHIKSHA SAMITI RAJPUT Pradesh @yahoo.com HARDA,HARDA AAROGYAA FOUNDATION FOR HEALTH PROMOTION DR RAJESH KUMAR COAT BAZAR,WARD No aarogyaafoundatio 8 SECERETARY Bihar Sitamarhi 9934691872 AND COMMUNITY BASED SUMAN 13,MAHARANI STHAN -

Pykara Pykara Is the Name of a Village and River Located 19 Km from Ooty

Pykara Pykara is the name of a village and river located 19 km from Ooty in the Indian State of Tamil Nadu. A boat house on the Pykara reservoir is an added attraction for tourists. Pykara boats of well protected fenced shoals. Pykara waterfalls flows through Murkurti, Pykara and Glen Morgan dams.. Mudumalai Before going to mudumali make sure you read this below point clearly OKDDSDD Obey Speed Limit Keep Noise level down Do not feed wildlife Do not dispose rubbish Shouting, teasing or chasing animals is prohibited Do not get out of your vechile Don't park vehicle on the road sideThose who violate the regulations will be prosecuted and punished according to law Dodebetta Doddabetta is the highest mountain in the Nilgiri Hills, at 2637 metres (8650 feet). There is a reserved forest area around the peak. It is 9 km from Ooty,on the Ooty-Kotagiri Road in the Nilgiris District of Tamil Nadu, South India. It is a popular tourist attraction with road access to the summit. The Chamundi Hills can be viewed from the peak.There is an observatory at the top of Doddabetta with two telescopes available for the public to enjoy the magnificent panoramic view of the whole district. The beautiful valley, plains of Coimbatore and the flat highlands of Mysore are visible from this point. Tea estate view point The Nilgiri region is remowned for its tea and most of the areas in ooty is sorrounded with the tea plantation. The tea estate or plantation is one of the tourist attraction and the tourist enjoy to go for a walk in the tea estate which gives them peaceful. -

Itinerary SOUTHERN SPLENDOUR(7 N) INR 38280

My Travel Itinerary SOUTHERN SPLENDOUR(7 N) INR 38280 Crafted by: Kishan Patel [email protected], 02682564666, 8153020555 TOUR OVERVIEW ACCOMMODATION ♦ 1 Night Stay in Mysore ♦ 2 Night Stay in Hassan ♦ 2 Night Stay in Hampi ♦ 2 Night Stay in Badami ♦ 1 Night Stay in Hubli SIGHTSEEING ♦ Majestic temples & gardens ♦ Dariya Daulat Bagh ♦ Gumbaz ♦ Tippu Fort and Temple ♦ Grand Maharaja Palace ♦ Brindavan Gardens ♦ Mysore Zoo and Maharaja Palace ♦ Coffee plantations ♦ Steep hills ♦ Countless stream ♦ Lush forest ♦ Tibetian Golden Temple ♦ Nisarga Dhama ♦ Talacaveri ♦ Bhagamandala ♦ Merkera Fort ♦ Omkareshwar Temple ♦ Abby Falls ♦ Western Ghats ♦ Edakkal Caves ♦ Kantapara Water Falls ♦ Soochipara Water Falls ♦ Meenmutti Waterfalls ♦ Green meadows of valleys ♦ White water springs ♦ Blue water lakes ♦ Tolpetti Forest ♦ Pookat Lake ♦ Chain Tree ♦ Queens of Hill station ♦ Ooty Lake ♦ Rose Garden and Botanical Garden ♦ Sim’s Park ♦ Lam’s Rock ♦ Dolphin Nose ♦ Tea Factory and Tea Gardens ♦ Doddabetta Peak MEALS ♦ Breakfast ♦ Dinner HOTEL Regenta Herald Hotel , Mysore Included in trip Sandesh The Prince , Mysore Included in trip Clarks Inn , Hassan Included in trip Clarks Inn Hampi Included in trip Clarks Inn Badami Included in trip Clarks Inn Hubli Included in trip SIGHTSEEING Dariya Daulat Bagh Daria Daulat Bagh (literally "Garden of the Sea of Wealth') is a palace situated in the city of Srirangapatna, near Mysore in southern India. ... The palace is built in the Indo-Saracenic style and is mostly made of teakwood. The palace has a rectangular plan and is built on a raised platform. Gumbaz Temple Gumbaz is the crypt of Mohammed Adil Shah, who was the Sultan of Bijapur. He was the seventh ruler of Adil Shah Dynasty. -

Third Route to Ooty Remains Only on Paper Even After Six Years

FOLLOW US ON facebook.com/ twitter.com/ thenilgirispost nilgirisPost youtube.com/ instagram.com/ Nilgiris Post thenilgirispostnews www.nilgirispost.com Edition - 6 Sunday, JULY 21 - 27, 2019 12 PAGES PAGES (5 - 8) COIMBATORE ESTABLISHED 2015 FREE / PRIVATE CIRCULATION Mohanlal starrer `Drishyam’ inspires murder; Munnar may go Ooty, Kodai way Heady threat: TASMAC spilling death youth killed by pals with encroachment regularisation in tribal areas 03 09 11 Third route to Ooty remains only on TOON CORNER paper even after six years Ooty Anish [email protected] The general public in Nilgiris are dissatisfied by the slow prog- ress of the administration in build- ing the third route to the hills. CoP lauds woman constable’s Tourist buses and other vehi- cles from Coimbatore and other presence of mind places come to Ooty through the Coimbatore: City Police Commissioner Su- heritage route of Mettupalayam, mit Sharan today appreciated the presence of Burliar, Coonoor , Kotagiri and mind of a woman constable in saving the life of Kunjappanai. Traffic congestion a 50-year-old differently able person, who had has increased day-by-day in this suddenly suffered severe chest pain a week route, particularly in Burliar, Coo- ago. noor and Kotagiri. The late Chief Minister J Jay- 2013. She gave the order to ease slow work, the regular mainte- The first grade constable Baby, attached to Also during stormy or rainy alalithaa had announced the con- traffic congestion and preserve the nance work on this route has also the Race Course Station, was on duty at the Dis- weather, mud and landslides on struction of a third route to Ooty natural beauty of the Nilgiris. -

Mumbai to Calicut Train Time Table

Mumbai To Calicut Train Time Table Nerveless Alaa always sulphates his riders if Roman is intromissive or reacclimatizes atheistically. Unlisted Ludvig festinateprejudiced, pleonastically. his Carmel calendars disregards zealously. Autogamic and artefactual Valentin bullyragging his bouts defaults Time taken to travel to Ooty trip Anamudi, Mannamalai and Meesapulimala distancing in Ooty in the state Tamil! Lokmanya Tilak Term to Kozhikode Train Ticket Prices vary with train more train ask the services which you choose to avail during my journey. Railway and calicut is it company group tours you are delivered through other. How do railway stations does Thane have? Just like date flight, bus or a cab to reach necessary to! By train time table, trains are other areas nadu, mannamalai and calicut are no notifications. We are not affiliated to the the IRCTC or any of the websites of the Indian Railways. It passes through its name with friends corporate or tour tea factory access to train time mumbai to table from mumbai! Some of factors, which means black mountain details: no active tenders and capital of best connection between mumbai once you get. Visit one of the last update. Find assess the transport options for extra trip from Mumbai CST to Thane Station page here. Other areas other areas points every day tell the Nilgiris district, Tamil Nadu, India popularly. However, it is important to remember that journey times may vary according to a number of factors, including seasonal weather conditions, local events or diversions. There may vary from! They contain a train time progressed, trains that were converted to calicut; university of cities in ooty bus to. -

OUTREACH) Taken-Up by JSS College of Pharmacy, Ooty in the Last 5 Years

The Social Responsibility Initiatives (OUTREACH) Taken-up by JSS College of Pharmacy, Ooty in the Last 5 Years 2012-13: NSS Activities 1. July 10th - Participated in the Anti Ragging Rally in coordination with Police Department Ooty. Nilgiris district Superintendent of Police Mr. Nizamuddin inaugurated the awareness rally. DSPs Ms. Anita and Mr. Rangaswamy were the other officials. Students of different colleges viz. Government Arts College Ooty, Emerald Heights College Ooty, CSI Engineering College, Ketti participated in the Awareness rally programme. The rally started from Ooty bus stand and went through ATC bus stand and reached HADP ground. 2. August 08th Participated in the Disaster Management –A Holistic Perspective programme at JSS College of Pharmacy Auditorium. Scientists & Engineering wing of RERF, Brahma Kumaris-Mount Abu, Sri Abu Babaji Charitable Trust-Ooty, Indian Red Cross Society were the other participants. This one day programme kindled the student volunteers the way of reacting during the land slide and natural calamities, Since Nilgiris is more prone to natural calamities. 3. August 17th –Celebrated Sadhbavana Diwas on the eve of birth anniversary of Former Prime Minister Sri Rajiv Gandhi. Mr. Rahmath from Johan Foundation conducted Personality development for the Fresh NSS Volunteers. The programme started at 10.am and went on till 01pm, since the programme was one to one interaction volunteers enthusiastically participated. st 4. December 01 , Participated in the World Aids day awareness rally in collaboration with Tamil Nadu State Aids Control Society (TANSACS) Ooty. Rally stated from Municipal bus stand and ended at Shanthi Vijay School at ATC bus stop. About 70 NSS Volunteers participated in the rally. -

Winter School Leaflet-16

Address for correspondence: PROFORMA FOR APPLICATION 1. Full Name (in capital letters): ………….......................... Information Brochure Dr. S. Manivannan 2. Designation: ……………………………........................... Principal Scientist (SWCE) & Course Director ICAR-Indian Institute of Soil and Water Conservation 3. Office address: ….………….......................................... ICAR Sponsored Winter School Regional Centre, Fern Hill Post, 4. Address to which reply should be sent (in block letters) On Udhagamandalam, The Nilgiris (Give telegraphic, fax, e-mail address and mobile no.) Advanced technologies in watershed hydrology ........................................................................................... Tamil Nadu - 643 004 to mitigate climate change impact on soil and 5. Permanent address: ..................................................... water resources Phone (O): 0423-2443992 5. Date of birth: …………………………….......................... Fax : 0423-2446757 7. Sex (male/female): ……………………........................... Mobile : 09442109091 8. Marital status: …………………………............................ 01-21 November, 2016 E-mail : [email protected] 9. Teaching/Research/Professional experience (mention post held ) and number of publications: ....................... Course Director Also can contact: 10. Mention if you have participated in any Summer/ Winter School/ Short Course, etc. during the Dr. S. Manivannan previous three years under ICAR / Other Principal Scientist (Soil & Water Cons. Engg.) Dr. P. Raja organizations : ........................................................... -

ABOUT US Travelpomo India (OPC) Private Limited

ABOUT US Your online travel partner Travelpomo India (OPC) Private Limited www.travelpomo.com Travelpomo India (OPC) Private Limited 3/128 KMP Nagar, Kumaresapuram, Koothappar(PO) Trichy-620013 Trichy | Tamilnadu 620013 | INDIA M: +91-9600262024 M: +91- 8610309973 [email protected] www.travelpomo.com CIN: U63090TN2020OPC139518 PAN: AAICT2410Q Flights | Hotels | Bus | Car Rental | Holidays | Air Charters Dear Mr. Harish, Thank you for your enquiry in Travelpomo. Greetings from Travelpomo!!! As per your enquiry we have given you day by day itinerary plan with cost estimation for 3 Days and 2 Night Economy + Adventure Ooty Friends Holiday Package for 8 adults, please go through the plan and revert us your feedback. Accommodation details: Hotel: Preferable hotels - Time Palace/Similar hotels (2 Star Category) (2 Family Room 4 in 1 Room)-1 Night+ Crest Valley(Campsite)-1 Night tent stay “We prefer a safe and secure hotel for our guest. For family security is the first preference, and Travelpomo will take all responsibility in guest accommodation and Comfort in stay” Transport details: You will have a dedicated car (Tavera / Maxi Cab -Non Ac) and a driver throughout your trip, Travelpomo will allocate a driver cum semi guide to make sure you have a perfect privacy trip. The car and the driver will be available from morning 8:30 am to evening 6:00 pm, Travelpomo will make sure the timing and driver allocated will be more flexible according to your requirements for Early Morning Pickup. On request outstation pickup and drop will -

JSS University, Mysore

National Service Scheme ANNUAL REPORT Submitted to State Liaison officer NSS Cell, M.S. Building Ambedkar Veedhi Bangalore-01 Submitted by JSS University, Mysore 2015-16 JSS UNIVERSITY (Established under section 3 of the UGC Act 1956) JSS Medical Institutions Campus Sri Shivarathreeshwara Nagar, Mysore-570015, Karnataka, India Accredited Grade „A‟ by NAAC National service scheme REPORT FOR THE PERIOD ENDING : April 2015 to March 2016 BASIC INFORMATION ABOUT UNIVERSITY: STATE : Karnataka UNIVERSITY : JSS University NAME OF THE PROGRAMME COORDINATOR : Dr. K.L.Krishna WHETHER PART TIME/FULL TIME : Part Time DATE OF APPOINTMENT : 21/07/2016 NO. OF SUPPORTING STAFF FOR NSS AT UNIVERSITY : 02 DATE OF LAST MEETING OF UNIVERSITY LEVEL ADVISORY COMMITTEE : 27/04/2015 NSS VOLUNTEERS STRENGTH : 400 TOTAL NO. OF STUDENT POPULATION OF THE UNIVERSITY : 4534 NSS STRENGTH ALLOCATED BY THE STATE GOVT. : 400 ACTUAL NO. OF NSS VOLUNTEERS : 400 ACTUAL NO. OF NSS VOLUNTEERS :M-214, F-186,TOTAL=400 NO. OF COLLEGES : 04 Colleges TOTAL NO. OF NSS UNITS : 04 Units NO. OF PROGRAMME OFFICERS IN POSITION : 04 Officers NO. OF PROGRAMME OFFICERS TRAINED : 04 Officers NO. OF PROGRAMME OFFICERS TO BE TRAINED : Nil NO. OF VILLAGES ADOPTED : 04 Villages FUNDS FOR NSS REGULAR/SPECIAL PROGRAMMES Funds received by the University: Rs. 3, 51, 000.00 FOR REGULAR ACTIVITIES FOR SPECIAL CAMPS DAY OF RECEIPT: 03/11/15 DAY OF RECEIPT: 03/11/15 AMOUNT RECEIVED: Rs. 100,000.00 AMOUNT RECEIVED: Rs. 90,000.00 PER CAPITA EXPENDITURE FOR ESTABLISHMENTAT UNIVERSITY LEVEL : Rs.300/volunteers SPECIAL CAMPING PROGRAMME: I. TOTAL NO. OF VOLUNTEERS PARTICIPATED : 200 II. -

Consultancy Services for Preparation of Master Plan and Detailed Strategy for Tamil Nadu Integrated Tourism Promotion Project - Phase 1 (95 Locations)

Tamil Nadu Infrastructure Fund Management Corporation Limited Request for Expression of Interest (REOI) Consultancy Services for Preparation of Master Plan and Detailed Strategy for Tamil Nadu Integrated Tourism Promotion Project - Phase 1 (95 locations) August 2019 REOI Reference Number: 06/TNIFMC/2019-20 Tamil Nadu Infrastructure Fund Management Corporation Limited No. 19, TP Scheme Road, RA Puram, Chennai – 600 028 Request for Expression of Interest (REOI) for “Consultancy Services for preparation of Master Plan and Detailed Strategy for the Tamil Nadu Integrated Tourism Promotion Project - Phase 1 (95 Locations)” DISCLAIMER The information contained in this ‘Request for Expression of Interest’ document (the “REOI”) or subsequently provided to Applicant(s), whether verbally or in documentary or any other form, by or on behalf of the Tamil Nadu Infrastructure Fund Management Corporation Limited (TNIFMC) (the “Authority”) or any of their representatives, employees or advisors., is provided to Applicant(s) on the terms and conditions set out in this REOI and such other terms and conditions subject to which such information is provided. This REOI is not an agreement and is neither an offer nor invitation by the Authority to the prospective Applicants or any other person. The purpose of this REOI is to provide interested parties with information that may be useful to them in the formulation of their application for shortlisting pursuant to this REOI. This REOI includes statements, which reflect various assumptions and assessments arrived at by the Authority in relation to the project. Such assumptions, assessments and statements do not purport to contain all the information that each Applicant may require. -

Guidelines for Radio Astronomy

GUIDELINES FOR THE PARTICPANTS OF Pulsar Observatory for Students (2012) RAC welcomes you for the POS 2012 Program. You are requested to abide by the following rules for use of facilities at RAC, Ooty. 1. Please see the RAC notice board and our web page for the academic program (http://ncra.tifr.res.in/~rpl/pos.html) 2. Students may make use of the RAC Library only during regular working hours. The library key will NOT be issued to a visiting student. Please introduce yourself to the Library-In-Charge (Mrs. M. Karpagam ) and enter your name in the visitor’s register. 3. Students are not allowed to borrow any books from the library. Students will be responsible for safe keeping of the books. The books must NOT be taken out of the building to your rooms. 4. Limited photocopy facility will be available on the guide’s recommendation. For any help, please contact Mrs. M. Karpagam, Library-In-Charge 5. Students using any equipment in the Observatory for their project work must do so with the guide’s approval. 6. Computer facilities at RAC are to be used only for the work related to the project. For details contact Mr. R. Venkatasubramani (RVS) (Inter Com No.40) 7. Canteen facilities can be availed of by the students. Please inform the canteen well in advance if you wish to take breakfast/lunch/dinner. 8. Students are required to return all RAC items available with them to his/her guide before leaving the Institute on completion of the project. 9. Travel allowances only for outstation candidates will be paid as mentioned in the letters. -

Ooty Sightseeing Places Queen of Hill Station………

Welcome to The Grand Inn Travels Ooty Sightseeing Places Queen of Hill Station………. The Grand Inn Hotel Mysore 1ST PLACE - ROSE GARDEN About the rose garden : The Government Rose Garden is situated on the slopes of the Elk Hill in Vijayanagaram of Ooty town in Tamil Nadu, India at an altitude of 2200 meters. Contents. 2ND PLACE: OOTY LAKE About ooty lake : Ooty lake is also called as ooty boat house is located in Ooty in the Nilgiris district and 1 km from ooty bus stand., Tamil Nadu, India. It covers an area of 65 acres 3RD PLACE : GOVERNMENT BOTANICAL GARDEN About- The Government Botanical Garden is a botanical garden in Udhagamandalam, near Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu state, India laid out in 1848. The Gardens, divided into several sections, cover an area of around 55 hectares, and lie on the lower slopes of Doddabetta peak. The garden has a terraced layout. 4th Place : Winlock Downs 9th Mile Shooting Point About - Shooting point is a beautiful hill slope in Ooty in Tamilnadu.Cool golden sunlight afternoons are the speciality of this place 5th Place -Doddabetta Peak About - Doddabetta is the highest mountain in the Nilgiri Mountains at 2,637 metres. The name derived from two Kannada words, Dodda means Big and betta means Hill, making it Doddabetta. There is a reserved forest area around the peak 6th Place – Dolphin nose About - Dolphin's Nose Viewpoint is a tourist spot in Coonoor, The Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu. Dolphin's Nose is well over 1,550 Meter above sea level, 10 km from Coonoor and is a spectacular spot to visit.