Download (499Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{TEXTBOOK} Level 3: Doctor Who: Face the Raven Kindle

LEVEL 3: DOCTOR WHO: FACE THE RAVEN Author: Nancy Taylor Number of Pages: 64 pages Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 Publisher: Pearson Education Limited Publication Country: Harlow, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781292206196 DOWNLOAD: LEVEL 3: DOCTOR WHO: FACE THE RAVEN Level 3: Doctor Who: Face The Raven PDF Book These details may be relatively unimportant to the average dancer, but it is essential that they should be correctly applied when dealing with the printed word. The book explores the attitudes, knowledge and understanding that a practitioner must adopt in order to start or develop successful Sustained Shared Thinking. In addition Ruppert gives a very useful account of his thinking about the methodology of Constellations as a means of achieving understanding and integration. If you are thinking of buying an electric vehicle or already drive one, then this book is a must for you. we remove fuel-supply line with nozzles. They reflect the actual SAT Subject Test in length, question types, and degree of difficulty. Level 3: Doctor Who: Face The Raven Writer 2016 and gives you all the essential facts about the W110 sedan and 111 and 112 two- and four-door series. Roger Mills and staff accomplished the "miracle" in the Modello and Homestead Gardens Housing Projects, applying the Three PrinciplesHealth Realization approach based on a new spiritual psychology. From Brazilian favelas to high tech Boston, from rural India to a shed inventor in England's home counties, We Do Things Differently travels the world to find the advance guard re-imagining our future. The volume assembles a rich diversity of statements, case studies and wider thematic explorations all starting with indigenous peoples as actors, not victims. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

The Wall of Lies #174

The Wall of Lies Number 174 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA Final STATE Adelaide, September–October 2018 WEATHEr: Autumn Brought Him Free Leadership Vote Delays Who! by staff writers Selfish children spoil party games. The Liberal Party leadership spill of 24 August 2018 had an unfortunate consequence; preempting Doctor Who. Due to start at 4:10pm on Friday the 24th, The Magician's Apprentice was cancelled for rolling coverage of the three way party vote. The episode did repeat at 4.25am that day. Departing Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull frankly told us (The Wall of Lies 155, July 2015) that he had never watched Doctor Who. Incoming Prime Minister Scott Morrison thoughts on the show are not recorded. O The Wall of Lies lobbies successive u S t Communications Ministers to increase So on Regeneration: the 29th and 30th Prime resources and access for preserving the n! Ministers reunite for an absolutely dreadful nation’s television heritage. anniversary show. Free Tickets for Doctor Who Club! by staff writers BBC Worldwide and Sharmill Films come through again! On 20 August 2018 Sharmill Films said they had a deal with the BBC to present the as SFSA magazine # 33 yet unnamed series 11 premiere of Doctor Who in Australian cinemas. O u N t No ow Sharmill has presented the screenings of ! The Day of The Doctor (24 November 2013), Deep Breath (24 August 2014), The Power of the Daleks and The Return of Doctor Mysterio (12 November and 26 December 2016, respectively), The Pilot, Shada, and Twice Upon a Time (16 April, 24 November and 26 December 2017). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

Doctor Who's Feminine Mystique

Doctor Who’s Feminine Mystique: Examining the Politics of Gender in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke Professor Sarah Houser, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs Professor Kimberly Cowell-Meyers, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs University Honors in Political Science American University Spring 2014 Abstract In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan examined how fictional stories in women’s magazines helped craft a societal idea of femininity. Inspired by her work and the interplay between popular culture and gender norms, this paper examines the gender politics of Doctor Who and asks whether it subverts traditional gender stereotypes or whether it has a feminine mystique of its own. When Doctor Who returned to our TV screens in 2005, a new generation of women was given a new set of companions to look up to as role models and inspirations. Strong and clever, socially and sexually assertive, these women seemed to reject traditional stereotypical representations of femininity in favor of a new representation of femininity. But for all Doctor Who has done to subvert traditional gender stereotypes and provide a progressive representation of femininity, its story lines occasionally reproduce regressive discourses about the role of women that reinforce traditional gender stereotypes and ideologies about femininity. This paper explores how gender is represented and how norms are constructed through plot lines that punish and reward certain behaviors or choices by examining the narratives of the women Doctor Who’s titular protagonist interacts with. Ultimately, this paper finds that the show has in recent years promoted traits more in line with emphasized femininity, and that the narratives of the female companion’s have promoted and encouraged their return to domestic roles. -

Torchwood Doctor Who: Wicked Sisters Big Finish

ISSUE: 140 • OCTOBER 2020 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM THE TENTH DOCTOR AND RIVER SONG TOGETHER AGAIN, BUT IN WHAT ORDER? PLUS: BLAKE’S 7 | TORCHWOOD DOCTOR WHO: WICKED SISTERS BIG FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULLCAST AUDIO WE LOVE STORIES! DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND OR ABOUT BIG FINISH DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, WWW.BIGFINISH.COM Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The @BIGFINISH Avengers, The Prisoner, The THEBIGFINISH Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: BIGFINISHPROD 1999 and Survivors, as well BIG-FINISH as classics such as HG Wells, BIGFINISHPROD Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the SUBSCRIPTIONS Opera and Dorian Gray. If you subscribe to our Doctor We also produce original BIG FINISH APP Who The Monthly Adventures creations such as Graceless, The majority of Big Finish range, you get free audiobooks, Charlotte Pollard and The releases can be accessed on- PDFs of scripts, extra behind- Adventures of Bernice the-go via the Big Finish App, the-scenes material, a bonus Summereld, plus the Big available for both Apple and release, downloadable audio Finish Originals range featuring Android devices. readings of new short stories seven great new series: ATA and discounts. Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence Secure online ordering and Investigate, Blind Terror, details of all our products can Transference and The Human be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF Frontier. BIG FINISH WELL, THIS is rather exciting, isn’t it, more fantastic THE DIARY OF adventures with the Tenth Doctor and River Song! For many years script editor Matt Fitton and I have both dreamed of RIVER SONG hearing stories like this. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

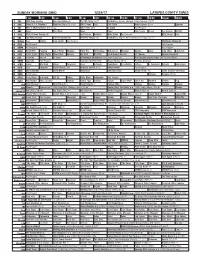

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Julia Franco First Year Seminar Science Fiction Tuesday 9:30-10:45

Julia Franco First Year Seminar Science Fiction Tuesday 9:30-10:45/ Friday 9:30-12:15 Allegories in Time and Space1 On November 23rd 1963, the BBC launched their new TV show Doctor Who. They did not anticipate the cultural phenomenon.what would grow out of their low budget show with cheesy special effects. British children were enchanted by William Hartnal’s Doctor and his companions: Ian, Barbara and Susan, and gleefully scared by the fearsome salt shakers of doom: The Daleks. The stories were anywhere from 4 to 12 parts, each around 25 minutes and were serialized weekly. But lying beneath the light hearted self resolving stories ran deeper elements reflecting attitudes towards history and current events. Deeply rooted in the series was the allegory to World War II. The Daleks take the place of the Nazis and the Time Lords therefore fill the opposing role of the Alliance. At many points, the story reads as if it is a future history of what would have happen if the Nazis had won World War II. This tapped into the subconscious fears of the nation as the war was still fresh in the minds of the parents of Britain. But also tied into the contemporary fears of the Cold War and the Soviet threat. These allegorical elements along with the characters in Doctor Who, such as the Daleks and the Time Lords, that correspond to actual historical events and people make the show what it is today: timeless and timely. The Daleks would not exist if not for one man- Terry Nation. -

Happy Birthday Doctor Who! the Light at the End Celebrate with Our Multi-Doctor Adventure!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES HAPPY BIRTHDAY DOCTOR WHO! THE LIGHT AT THE END CELEBRATE WITH OUR MULTI-DOCTOR ADVENTURE! PLUS! ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT OUR VARIOUS ANNIVERSARY RELEASES… ISSUE 57 • NOVEMBER 2013 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 1 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 2 Welcome to Big Finish! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio drama and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. We publish a growing number of books (non-fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. You can access a video guide to the site by clicking here. Subscribers get more at bigfinish.com! If you subscribe, depending on the range you subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a bonus release and discounts. www.bigfinish.com @bigfinish /thebigfinish VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 3 VORTEX MAGAZINE | PAGE 4 EDITORIAL ISSUE 57 • NOVEMBER 2013 o, The Light at the End is out. Didn’t expect that, did you? You could have heard the mass exhaling of Big Finish employees S across the country when I clicked the ‘yes’ button for that (until the website also exhaled and gave up for a time – huge thanks SNEAK PREVIEWS to the Hughes Media web team for dealing with that so efficiently). -

Program Listings” Christopher C

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSJANUARY 2014 PREMIERES SUNDAY, JANUARY 5 AT 9 P.M. ON WXXI-TV Season 4 of the international hit finds aristocrats coping with last season’s shocking finale. Change is in the air as three generations of the Crawley family have conflicting interests in the estate. Paul Giamatti makes an appearance alongside the beloved returning ensemble, including Dame Maggie Smith, Elizabeth McGovern, Hugh Bonneville, Michelle Dockery, Jim Carter, Joanne Froggatt, guest star Shirley MacLaine and many others. AFTER DOWNTON LIVE SUNDAY, JANUARY 5 & 12 AT 11 P.M. ON WXXI-TV After Downton Abbey be sure to stay tuned for After Downton Live, WXXI’s “post-game” wrap up show. Host Danielle Abramson and special local guests will dissect the episode, invite viewers to share their take on the show by calling (866) 264-5904 or on Twitter using hashtag: #ADLWXXI, and talk about what “buzz” is brewing about the upcoming episode. EVAN DAWSON JANUARY 25 AT THE LITTLE THEATRE DETAILS INSIDE>> JOINS WXXI NEWS DETAILS INSIDE>> 384 East Avenue Inn & Suites Ferrel’s Garage Leary’s Rochester Area Booksellers Association AMC Lowes Webster Ferris Hills at West Lake Legacy Dental Laboratory Rochester Area Community Foundation Accu-Roll Inc. Festa Italia Productions LTD Lento Restaurant Rochester Brainery Advanced Motion Systems Finger Lakes Grassroots Festival LiDestri Foods, Inc. Rochester Broadway Theatre League Alesco Advisors First National Rochester Fringe Festival Lifespan of Greater Rochester Rochester City Ballet Alfred University Fox Run Vineyards Lift Bridge Book Shop Rochester City School District Allendale Columbia School Freed Maxick, CPAs, P. -

Read Book Doctor Who Character Encyclopedia Pdf Free Download

DOCTOR WHO CHARACTER ENCYCLOPEDIA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK DK,Jason Loborik,Annabel Gibson,Moray Laing | 216 pages | 02 Apr 2013 | Dorling Kindersley Ltd | 9781409325710 | English | London, United Kingdom Doctor Who Character Encyclopedia | Tardis | Fandom Main article: Doctor Who spin-offs. Both are Eleventh Doctor episodes. He gains his surname when he returns in the Twelfth Doctor episode, " Deep Breath ". Kennedy's American University speech of 10 June days prior to the episode's 22 November setting ; the episode's cliffhanger end takes place in the early evening of 22 November, at or about the moment of Kennedy's assassination. The Wheel in Space. Doctor Who. The War Games. Doctor Who Magazine Despite only small scenes in " Mummy on the Orient Express " and " Flatline ", he was credited for both. After appearing in ten episodes most significantly in " The Caretaker ", " In the Forest of the Night ", " Dark Water " and " Death in Heaven " , he died in the pre-credit scene of "Dark Water", but he still appeared in the post-credit scenes of the episode, and its follower. The turning point for the finale was when Danny sacrificed himself to save Earth from "Missy" the Master. His name is additionally shown on- screen in a newspaper in " Turn Left ", in which he is reported killed in a Doctor-less version of the events of " Smith and Jones ". The Abominable Snowmen. The Web of Fear. BBC One. Wells is the only named character to appear in all three series, although Anthony Debaeck's unnamed French newsreader does as well, and the TARDIS is heard in all three. -

OMC | Data Export

Richard Scully, "Entry on: Doctor Who (Series, S05E12-13): The Pandorica Opens / The Big Bang by Lindsey Alford , Toby Haynes, Steven Moffat", peer-reviewed by Elizabeth Hale and Daniel Nkemleke. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/90. Entry version as of October 05, 2021. Lindsey Alford , Toby Haynes , Steven Moffat Doctor Who (Series, S05E12-13): The Pandorica Opens / The Big Bang United Kingdom (2010) TAGS: Classical myth Roman Britain Roman history We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Doctor Who (Series, S05E12-13): The Pandorica Opens / The Big Title of the work Bang Studio/Production Company British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Country of the First Edition United Kingdom Original Language English First Edition Date 2010 First Edition Details June 19, 2010 / June 26, 2010 Running time 50 min (each) September 6, 2010 (DVD [Region 2]); July 26, 2016 (DVD [Region Date of the First DVD or VHS 1]) Awards Hugo Award, Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Film (2011) Genre Science fiction, Television series, Time-Slip Fantasy* Target Audience Crossover Author of the Entry Richard Scully, University of New England, [email protected] Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Daniel Nkemleke, Universite de Yaounde 1, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof.