Immigration and Youthful Illegalities in a Global Edge City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

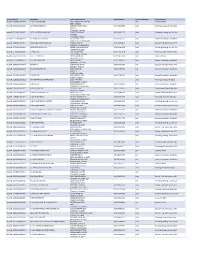

Alpha ELT Listing

Lienholder Name Lienholder Address City State Zip ELT ID 1ST ADVANTAGE FCU PO BX 2116 NEWPORT NEWS VA 23609 CFW 1ST COMMAND BK PO BX 901041 FORT WORTH TX 76101 FXQ 1ST FNCL BK USA 47 SHERMAN HILL RD WOODBURY CT 06798 GVY 1ST LIBERTY FCU PO BX 5002 GREAT FALLS MT 59403 ESY 1ST NORTHERN CA CU 1111 PINE ST MARTINEZ CA 94553 EUZ 1ST NORTHERN CR U 230 W MONROE ST STE 2850 CHICAGO IL 60606 GVK 1ST RESOURCE CU 47 W OXMOOR RD BIRMINGHAM AL 35209 DYW 1ST SECURITY BK WA PO BX 97000 LYNNWOOD WA 98046 FTK 1ST UNITED SVCS CU 5901 GIBRALTAR DR PLEASANTON CA 94588 W95 1ST VALLEY CU 401 W SECOND ST SN BERNRDNO CA 92401 K31 360 EQUIP FIN LLC 300 BEARDSLEY LN STE D201 AUSTIN TX 78746 DJH 360 FCU PO BX 273 WINDSOR LOCKS CT 06096 DBG 4FRONT CU PO BX 795 TRAVERSE CITY MI 49685 FBU 777 EQUIPMENT FIN LLC 600 BRICKELL AVE FL 19 MIAMI FL 33131 FYD A C AUTOPAY PO BX 40409 DENVER CO 80204 CWX A L FNCL CORP PO BX 11907 SANTA ANA CA 92711 J68 A L FNCL CORP PO BX 51466 ONTARIO CA 91761 J90 A L FNCL CORP PO BX 255128 SACRAMENTO CA 95865 J93 A L FNCL CORP PO BX 28248 FRESNO CA 93729 J95 A PLUS FCU PO BX 14867 AUSTIN TX 78761 AYV A PLUS LOANS 500 3RD ST W SACRAMENTO CA 95605 GCC A/M FNCL PO BX 1474 CLOVIS CA 93613 A94 AAA FCU PO BX 3788 SOUTH BEND IN 46619 CSM AAC CU 177 WILSON AVE NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49534 GET AAFCU PO BX 619001 MD2100 DFW AIRPORT TX 75261 A90 ABLE INC 503 COLORADO ST AUSTIN TX 78701 CVD ABNB FCU 830 GREENBRIER CIR CHESAPEAKE VA 23320 CXE ABOUND FCU PO BX 900 RADCLIFF KY 40159 GKB ACADEMY BANK NA PO BX 26458 KANSAS CITY MO 64196 ATF ACCENTRA CU 400 4TH -

APPENDIX B Cultural Resources Assessment

APPENDIX B Cultural Resources Assessment 3700 Riverside Drive Mixed-Use Project Cultural Resources Assessment prepared for City of Burbank 150 North Third Street Burbank, California 91502 Contact: Daniel Villa, Senior Planner prepared by Rincon Consultants, Inc. 250 East 1st Street, Suite 301 Los Angeles, California 90012 August 2020 Please cite this report as follows: Madsen, A., M. Strother, B. Campbell-King, S. Treffers, and S. Carmack 2020 Cultural Resources Assessment for the 3700 Riverside Drive Mixed Use Project, City of Burbank, Los Angeles County, California. Rincon Consultants Project No. 19-08998. Report on file at the South Central Coastal Information Center, California State University, Fullerton. Table of Contents Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Unanticipated Discovery of Cultural Resources ............................................................................. 1 Unanticipated Discovery of Human Remains ................................................................................ 2 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Location and Description ........................................................................................ 3 Personnel ........................................................................................................................... -

Contractor List

Active Licenses DBA Name Full Primary Address Work Phone # Licensee Category SIC Description buslicBL‐3205002/ 28/2020 1 ON 1 TECHNOLOGY 417 S ASSOCIATED RD #185 cntr Electrical Work BREA CA 92821 buslicBL‐1684702/ 28/2020 1ST CHOICE ROOFING 1645 SEPULVEDA BLVD (310) 251‐8662 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met UNIT 11 TORRANCE CA 90501 buslicBL‐3214602/ 28/2021 1ST CLASS MECHANICAL INC 5505 STEVENS WAY (619) 560‐1773 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con #741996 SAN DIEGO CA 92114 buslicBL‐1617902/ 28/2021 2‐H CONSTRUCTION, INC 2651 WALNUT AVE (562) 424‐5567 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia SIGNAL HILL CA 90755‐1830 buslicBL‐3086102/ 28/2021 200 PSI FIRE PROTECTION CO 15901 S MAIN ST (213) 763‐0612 subc Special Trade Contractors, NEC GARDENA CA 90248‐2550 buslicBL‐0778402/ 28/2021 20TH CENTURY AIR, INC. 6695 E CANYON HILLS RD (714) 514‐9426 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con ANAHEIM CA 92807 buslicBL‐2778302/ 28/2020 3 A ROOFING 762 HUDSON AVE (714) 785‐7378 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met COSTA MESA CA 92626 buslicBL‐2864402/ 28/2018 3 N 1 ELECTRIC INC 2051 S BAKER AVE (909) 287‐9468 cntr Electrical Work ONTARIO CA 91761 buslicBL‐3137402/ 28/2021 365 CONSTRUCTION 84 MERIDIAN ST (626) 599‐2002 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia IRWINDALE CA 91010 buslicBL‐3096502/ 28/2019 3M POOLS 1094 DOUGLASS DR (909) 630‐4300 cntr Special Trade Contractors, NEC POMONA CA 91768 buslicBL‐3104202/ 28/2019 5M CONTRACTING INC 2691 DOW AVE (714) 730‐6760 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia UNIT C‐2 TUSTIN CA 92780 buslicBL‐2201302/ 28/2020 7 STAR TECH 2047 LOMITA BLVD (310) 528‐8191 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia LOMITA CA 90717 buslicBL‐3156502/ 28/2019 777 PAINTING & CONSTRUCTION 1027 4TH AVE subc Painting and Paper Hanging LOS ANGELES CA 90019 buslicBL‐1920202/ 28/2020 A & A DOOR 10519 MEADOW RD (213) 703‐8240 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia NORWALK CA 90650‐8010 buslicBL‐2285002/ 28/2021 A & A HENINS, INC. -

An Exploration of Two Gated Communities in Istanbul 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Thesis Structure 4

BASAK TANULKU BA, MA AN EXPLORATION OF TWO GATED COMMUNITIES IN ISTANBUL Ph.D. THESIS SUBMITTED TO LANCASTER UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2009 1 I dedicate this thesis to my mother and father... 2 I, Basak Tanulku, declare that this thesis is my own work, and this is not submitted elsewhere for the award of a higher degree. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (REMOVED) 4 ABSTRACT In the process of globalisation, big cities in Turkey have witnessed the emergence of gated communities a much debated issue in public opinion. This thesis is a comparative research, which distinguishes it methodologically from the rest of the Turkish literature. Contrary to the mainstream literature, I will show that gated communities interact with their surroundings, rather than being isolated housing developments. For this purpose, I selected the communities of Istanbul Istanbul and Kasaba built by the same developer company in Gokturk and Omerli. I have four main interests in this research. First, I examine the relations established with the residents in nearby communities, the local populations and municipalities which lead to economic, political and cultural changes in Gokturk and Omerli. Second, I examine how residents establish boundaries with different groups. In doing this, I argue that gated communities are the reflections of different class and cultural groups so that each social group has its “socially situated symbolic capitals” relevant for that group. Third, I also examine how space is shaped by and shapes people’s lives. For this purpose, I examine the competition between imaginary and real spaces, i.e. “designed” and “lived” places, which gives interesting results about how residents experience their homes leading to the re- evaluation of “sign-value”. -

IL JE Urr Urr JE Rn Volume 21 Spring 1992 Number 1

T SOCIE'I'Y W<IDIB1 I:N:O"'USTB,IAL .AB,CH:EOLOGY ~ JE \Y/Yl ~ IL JE urr urr JE rn Volume 21 Spring 1992 Number 1 When Campbell's said "Can't," Camden said "Can!" "The Soup" goes down in Camden, N.J. The century-old Campbe ll Soup factory along the Delaware River succumbed to the demolition contractor las t Nov. 3. The soup-can water tanks crashed onto the ru bble, but one may yet be saved. Ed Hille photo courtesy Phi/a. Inquirer. This is a story about a campaign to save one of the famous was closed and razed after Campbell began purchasing ready water tanks formerly atop the Campbell Soup plant in made cans. The majority of the plant was destroyed last fall. Camden, N.J. The company painted the tanks as giant soup Campbell Soup now is produced largely at plants in Paris, cans, and similar tanks have been a familiar sight on the Tex., and in several other states. Camden skyline since the tum of the century. In Nov. they Campbell Soup still maintains a presence in Camden were toppled when the soup factory was demolished for the through the Campbell Place complex, which includes corpo construction of a new General Electric facility. rate offices, laboratories, and a soup-tureen museum. Camp "The Soup," as it was known to many employees, traces its bell has made a commitment to the city and the state to roots to 1869, when it began as an obscure partnership in the maintain its headquarters in Camden, and these offices will be canning business. -

Appx-F HRER.Pdf

HRER Fair Oaks Overhead Rehabilitation November 2013 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS The City of Sunnyvale is undertaking the Fair Oaks Overhead Bridge Rehabilitation (Bridge No. 37C0765) in coordination with the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans). The project will widen the bridge, improve pedestrian crossing on Fair Oaks Avenue, and redesign the intersection and traffic signals at the intersections of Fair Oaks Avenue at Kifer Road and at Evelyn Avenue. The work will occur within the current right-of-way and the areas under the bridge. The project will include construction and staging areas located under the bridge and in the parking lot of the adjacent Home Depot. The project vicinity and location are illustrated in Figure 1 in Appendix A. The Area of Potential Effect (APE) for this project is generally defined by parcels immediately adjacent to the bridge encompassing the current right-of-way and proposed staging areas. See Appendix A, Figure 2 for a map of the APE. Those properties requiring evaluation are identified in Figure 3 Appendix A and given Map Reference numbers for identification. JRP Historical Consulting, LLC (JRP) prepared this Historical Resources Evaluation Report (HRER) to address the built environment within the APE. Two buildings, the residence at 303 Fair Oaks Avenue and Blue Bonnet Bar 208 S Fair Oaks Avenue, required formal evaluation (Map Ref #1 and #2). The Fair Oaks Overhead Bridge (37C0765) was constructed in 1967, and is 45 years old (Map Ref #3). Caltrans guidance states that properties 45 years or older should be evaluated to accommodate the long planning and design process for transportation projects. -

Historic Context & Survey Report

City of Huntington Beach Historic Context & Survey Report Prepared for: City of Huntington Beach Planning and Building Department 2000 Main Street Huntington Beach, CA 92648 Prepared by: Galvin Preservation Associates Inc. 231 California Street El Segundo, CA 90245 310.792.2690 * 310.792.2696 (fax) Updated 2014 This page intentionally left blank. i Executive Summary The City of Huntington Beach contracted Galvin Preservation Associates Inc. (GPA) in conjunction with Historic Resource Associates to conduct a citywide Historic Resources Survey to identify and evaluate potential historic resources in the city. The project team completed the studies on behalf of and under the guidance of the City of Huntington Beach’s Planning and Building Department with assistance from the Historic Resources Board of Huntington Beach. The historic context and the historical resource survey were developed in accordance with the Secretary of Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Historic Preservation and National Register Bulletin 24, Guidelines for Local Survey: A Basis for Preservation Planning. The GPA project team consisted of several professionals that meet the Secretary of Interior’s Professional Qualifications for History and Architectural History. The survey and development of the draft historic context were conducted from September 2008 to October 2009. The final report was completed from November 2009 to May 2010, updated in November, 2012 and finalized in June, 2014. The purpose of the survey is to update and expand the City’s existing 1986 Historic Resources Survey Report and to update the 1996 Historic and Cultural Resources Element (HCRE) of the City’s General Plan. Since the adoption of the HCRE, there has been significant redevelopment in the downtown area where many old buildings are located. -

DOES the BAY AREA HAVE a SOCIAL CENTER? Delimiting The

DOES THE BAY AREA HAVE A SOCIAL CENTER? Delimiting the Postmodern Urban Center of the San Francisco Bay Area by Colin Ahren Mattison A Thesis Presented to the FACULTY OF THE USC GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE (GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY) May 2016 Copyright 2016 Colin Ahren Mattison DEDICATION I dedicate this document to my wife, Breehan, and parents, Jeff and Marlene, for their constant support throughout this process. Without Bree’s support, both emotional and editorial, there is no way this thesis would have been completed. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to my mentor, Professor John Wilson, for motivating and navigating me on the path to completed thesis. Thank you also to my wife Breehan for watching our daughter on so many evenings when I was locked away in the office struggling through literature and grinding through this degree and this thesis. Without Bree’s faithful support, encouragement, assistance, and editorial guidance and word processing expertise, I would not have completed this thesis. I would also like to thank my mom and dad for supporting me through the constant changes my family endured and chose during the three years I spent in the Master’s program. Finally, I would also like to thank my daughter, Eilish, for all of her “helpies.” iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xi ABSTRACT xii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background -

Sample Chapter

01-5114-4 CH01 4/10/07 5:00 PM Page 1 Legoland 1 A primary LEGO showpiece, Miniland USA is a celebration of American achievements, a canvas to illustrate the diversification of its peoples and cultures, past and present. —Legoland website he main attraction of Legoland, a theme park just outside of Carlsbad, TCalifornia, is Miniland USA, which features miniatures of quintessen- tially American places built from 20 million Legos. Miniland has a replica of Washington, complete with federal museums, monuments, the White House, and the Capitol. It even has a miniature Georgetown and a working model of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. Other places in Miniland include the French Quarter of New Orleans, a New England fishing village, and Manhattan. The miniature of California is a hodgepodge of scenes, from an Orange County surfing town to Chinatown in San Francisco. What’s missing from Miniland, however, is the built landscapes so typi- cal of America—the housing subdivision, the retail strip mall, the office park—in short, suburbia. The irony is that Lego building blocks are per- fectly suited to make such places, especially the commercial structures. The basic Lego is a small rectangular block. Think of the ease with which the Miniland model makers could depict big-box retail centers or the low- slung, banded-window suburban office building. Just snap a bunch of 1 01-5114-4 CH01 4/10/07 5:00 PM Page 2 2 LEGOLAND Legos together and, presto, instant “edge city.”1 It is not as if the Lego folks could have missed knowing about suburban malls and office build- ings: Southern California is chock full of them. -

Proceedings Tenth World Congress of the Organization of World Heritage

Table Of Contents Message from the Mayor of Quito 7 Message from the Secretary General of OWHC 9 Introduction from the Getty Conservation Institute 11 Keynote Presentations 13 Historic Cities and their Survival in a Globalized World By Francesco Siravo 14 Micro-Finance Programmes in the Old City of Aleppo X World Congress of the Organization of World Heritage Cities Heritage World of the Organization of Congress World X By Maan Chibli 36 Manila Intramuros: An Island of Heritage By Augusto Villalón 46 4 Sleeping with the Enemy? Private Sector Involvement in World Heritage Preservation By Ron Van Oers 54 Report on the symposium and discussions By Dinu Bumbaru 66 Steering Committee List of Previous OWHC Publications 71 Steering Committee of the X World Congress of the OWHC 72 List of Previous OWHC Publications 72 X World Congress of the Organization of World Heritage Cities Heritage World of the Organization of Congress World X 5 X World Congress of the Organization of World Heritage Cities Heritage World of the Organization of Congress World X message from The Mayor of the Metropolitan District of Quito Quito and its people are grateful for having the presence of Mayors and delegates who honored us with their visit during the X World Congress for the Organization of World Heritage Cities - OWHC. The central topic of this important event, the “Revitalization of Historic Centers: How to involve all the social actors?” reflects the policy of this local government towards the conservation of our tangible and intangible heritage. We believe in the consolidation of comprehensive and plural policies that allow us to strengthen citizens’ participation identifying and revaluing our cultural heritage. -

The Restless Suburban Landscape (2012) Directed by Dr

CATANZARITE, MATTHEW, M.A. Edge Cites Revisited: The Restless Suburban Landscape (2012) Directed by Dr. Selima Sultana. 106pp. Edge cities characterized by high wage office based industries are of particular interest to planners since they reflect the type of development often associated with economic growth in the suburban landscape, but not well understood as shown by the debate over edge and edgeless cities. Very little research has been conducted that looks specifically to address whether Garreau’s edge cities of the 90’s have improved upon the concerns raised by critics in an effort to further replicate a traditional historical Central Business District (CBD) and sustain future growth or whether suburban landscapes have continued to resemble the edge city pattern at all. Very specifically, this thesis examines the following questions: (1) Can the combination of employment and population data be used to differentiate between edge and edgeless developments? (2) To what extent have edge cities of the 90’s adapted to further replicate traditional historical urban employment centers and to sustain future growth? (3) Have suburban landscapes continued to resemble the edge city, edgeless city or office sprawl pattern? (4) Can the existence and use of alternative/active transportation influence the development of edge cities? (5) Will edge cities of suburban Atlanta continue to develop relying on implementation of smart urbanism concepts and alternative transportation options? This research aimed at determining accurate geographic locations and boundaries of edge cities in the Atlanta MSA, using employment densities and characteristics, is able to precisely differentiate between areas that fit into the typology of edge cities, urban and suburban employment centers. -

City Names (By State)

State City County State Name Code Code City Name Code County Name ALABAMA 01 00124 ABBEVILLE 067 HENRY ALABAMA 01 00820 ALABASTER 117 SHELBY ALABAMA 01 00988 ALBERTVILLE 095 MARSHALL ALABAMA 01 01132 ALEXANDER CITY 123 TALLAPOOSA ALABAMA 01 01228 ALICEVILLE 107 PICKENS ALABAMA 01 01708 ANDALUSIA 039 COVINGTON ALABAMA 01 01852 ANNISTON 015 CALHOUN ALABAMA 01 01924 ANNISTON NORTHWEST 015 CALHOUN ALABAMA 01 02116 ARAB 095 MARSHALL ALABAMA 01 02956 ATHENS 083 LIMESTONE ALABAMA 01 03004 ATMORE 053 ESCAMBIA ALABAMA 01 03028 ATTALLA 055 ETOWAH ALABAMA 01 03076 AUBURN 081 LEE ALABAMA 01 04660 BAY MINETTE 003 BALDWIN ALABAMA 01 04684 BAYOU LA BATRE 097 MOBILE ALABAMA 01 05980 BESSEMER 073 JEFFERSON ALABAMA 01 07000 BIRMINGHAM 073 JEFFERSON ALABAMA 01 07792 BLUFF PARK 073 JEFFERSON ALABAMA 01 07912 BOAZ 055 ETOWAH ALABAMA 01 07912 BOAZ 095 MARSHALL ALABAMA 01 09136 BRENT 007 BIBB ALABAMA 01 09208 BREWTON 053 ESCAMBIA ALABAMA 01 09328 BRIDGEPORT 071 JACKSON ALABAMA 01 09400 BRIGHTON 073 JEFFERSON ALABAMA 01 10240 BRUNDIDGE 109 PIKE ALABAMA 01 13264 CENTER POINT 073 JEFFERSON ALABAMA 01 13672 CENTREVILLE 007 BIBB ALABAMA 01 14392 CHICKASAW 097 MOBILE ALABAMA 01 14464 CHILDERSBURG 121 TALLADEGA ALABAMA 01 15064 CITRONELLE 097 MOBILE ALABAMA 01 15136 CLANTON 021 CHILTON ALABAMA 01 16768 COLUMBIANA 117 SHELBY ALABAMA 01 17368 CORDOVA 127 WALKER ALABAMA 01 18976 CULLMAN 043 CULLMAN ALABAMA 01 19336 DADEVILLE 123 TALLAPOOSA ALABAMA 01 19360 DALEVILLE 045 DALE ALABAMA 01 19648 DAPHNE 003 BALDWIN ALABAMA 01 20104 DECATUR 103 MORGAN ALABAMA 01 20296 DEMOPOLIS