INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Howard Duff Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8489r0cj No online items Finding Aid for the Howard Duff Collection Processed by UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections staff. UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm ©2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Howard Duff 282 1 Collection Descriptive Summary Title: Howard Duff Collection Collection number: 282 Creator: Duff, Howard Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE: Advance notice required for access. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Property rights in the physical objects belong to the UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish if the Performing Arts Special Collectionsdoes not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Howard Duff Collection, 282, Performing Arts Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles. Biography Prolific character actor Howard Duff was born on November 24, 1913 in Bremerton, Washington and raised in Seattle. Duff's career spans the early days of radio when he played detective Sam Spade to his numerous roles in television, theater, and film. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present

Article The Korean Wave in the Middle East: Past and Present Mohamed Elaskary Department of Arabic Interpretation, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul 17035, South Korea; [email protected]; Tel. +821054312809 Received: 01 October 2018; Accepted: 22 October 2018; Published: 25 October 2018 Abstract: The Korean Wave—otherwise known as Hallyu or Neo-Hallyu—has a particularly strong influence on the Middle East but scholarly attention has not reflected this occurrence. In this article I provide a brief history of Hallyu, noting its mix of cultural and economic characteristics, and then analyse the reception of the phenomenon in the Arab Middle East by considering fan activity on social media platforms. I then conclude by discussing the cultural, political and economic benefits of Hallyu to Korea and indeed the wider world. For the sake of convenience, I will be using the term Hallyu (or Neo-Hallyu) rather than the Korean Wave throughout my paper. Keywords: Hallyu; Korean Wave; K-drama; K-pop; media; Middle East; “Gangnam Style”; Psy; Turkish drama 1. Introduction My first encounter with Korean culture was in 2010 when I was invited to present a paper at a conference on the Korean Wave that was held in Seoul in October 2010. In that presentation, I highlighted that Korean drama had been well received in the Arab world because most Korean drama themes (social, historical and familial) appeal to Arab viewers. In addition, the lack of nudity in these dramas as opposed to that of Western dramas made them more appealing to Arab viewers. The number of research papers and books focused on Hallyu at that time was minimal. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Starting Business

BONUS STARTUP RESOURCE KIT + Sample Business Plans Starting Your Own Business 4TH EDITION Everything You Need to Start a Successful Business! 1811v4_07.pdf Guide No.1811 Entrepreneur Media Inc. Publishers of Entrepreneur magazine, Entrepreneur’s Startups magazine, Entrepreneur.com Letter From Rieva Lesonsky, Editorial Director Dear Entrepreneur: Congratulations! By selecting this guide, you’ve taken a very significant step on the road to starting and running your own business. We thank you for your purchase, and wish you every success in your new business venture. For 30 years, Entrepreneur magazine has been helping people just like you successfully start, run and grow their businesses. This startup guide repre- sents hundreds of hours of interviews and research performed by our expert business staff. Inside you’ll find practical, step-by-step advice that clearly outlines the basic components of developing a successful business. To get the most out of the guide, start by reviewing the table of contents, which is a good place to start to find chapters dedicated to any subject you’re looking for: business structures, equipment, advertising and marketing, and much more. We also included a number of resource listings in the appendices in the back of the book. These easy-to-use sections will give you names, addresses and phone numbers for a variety of associations, publications and service providers. For many of you, this package will be enough. But others may want or need more. Depending on your knowledge and experience, you may want to learn more about the essentials of business startup. Luckily we also have a solution for that. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

November 2019

MOVIES A TO Z NOVEMBER 2019 D 8 1/2 (1963) 11/13 P u Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons (1960) 11/21 o A Day in the Death of Donny B. (1969) 11/8 a ADVENTURE z 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932) 11/5 S Ho Booked for Safekeeping (1960) 11/1 u Dead Ringer (1964) 11/26 S 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 11/27 P D Bordertown (1935) 11/12 S D Death Watch (1945) 11/16 c COMEDY c Boys’ Night Out (1962) 11/17 D Deception (1946) 11/19 S –––––––––––––––––––––– A ––––––––––––––––––––––– z Breathless (1960) 11/13 P D Dinky (1935) 11/22 z CRIME c Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) 11/1 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 11/16 w The Dirty Dozen (1967) 11/11 a Adventures of Don Juan (1948) 11/18 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 11/6 P D Dive Bomber (1941) 11/11 o DOCUMENTARY a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 11/8 R Brief Encounter (1945) 11/15 Doctor X (1932) 11/25 Hz Alibi Racket (1935) 11/30 m Broadway Gondolier (1935) 11/14 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 11/20 P D DRAMA c Alice Adams (1935) 11/24 D Bureau of Missing Persons (1933) 11/5 S y Dodge City (1939) 11/8 c Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More (1974) 11/10 w Burn! (1969) 11/30 z Dog Day Afternoon (1975) 11/16 e EPIC D All About Eve (1950) 11/26 S m Bye Bye Birdie (1963) 11/9 z The Doorway to Hell (1930) 11/7 S P R All This, and Heaven Too (1940) 11/12 c Dr. -

The Summer Chronicle

The Summer Chronicle llth Year, Number 6 Duke University, Durham, North Carolina Wednesday, June 17, 1981 Trustees OK hospital budget, rate hikes By Erica Johnston increase by 12 percent to 15 calls for an expense budget of Patients at Duke Hospital percent. $169.7 million, an increase of 8.5 will pay an average of 11 The hikes were part of the percent over last year's, and a percent more for their rooms Hospital's fiscal 1982 budget revenue budget of $175.4 starting July 1 due to an proposal presented to the million. increased revenue budget for executive committee by Andrew In response to a trustee's the Hospital approved by the Wallace, chief executive officer question, Wallace said Duke executive committee of the of the Hospital. Hospital "will still be the most Board of Trustees last Friday. The increase — the second for expensive in the Piedmont On July 1, rates will inrease room rates in six months — is region," but added that the rate from $216 to $231 or by nine needed to make the Hospital's by which Duke's room fees have percent for semi-private rooms, projected revenue budget exceed increased is lower than about from $220 to $240 for private the expense budget to balance half ofthe hospitals' in the area. rooms and from $580 to $705 inflationary factors and help Duke Hospital's rates are daily, or by 22 percent, for decrease the Hospital's $3.5 higher than other area rooms in the intensive care unit. million deficit, Wallace hospitals largely because Duke Charges for out-patient visits explained after the meeting. -

Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Via Zoom Meeting Platform 1. Call to Order 2. Public Comment 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Consent Agenda Items Approval of March 18, 2021 Regular Meeting Minutes Approval of March 2021 Payroll in the amount of $38,975.80 Approval of March 2021 Vouchers in the amount of $76,398.04 Treasury Reports for March 2021 Balance Sheet for March 2021 (if available) Deletion List – 5116 Items 5. Conflict of Interest 5. Communications 6. Director’s Report 7. Unfinished Business A. Library Opening Update B. Art Policy (N or D) 8. New Business A. Meeting Room Policy (N) B. Election of Officers 9. Other Business 10. Adjournment There may be an Executive Session at any time during the meeting or following the regular meeting. DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Legend: E = Explore Topic N = Narrow Options D = Decision Information = Informational items and updates on projects Parking Lot = Items tabled for a later discussion Current Parking Lot Items: 1. Grand Opening Trustee Lead 2. New Library Public Use Room Naming Jeanne Williams is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. Topic: Board Meeting Time: Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Pacific Time (US and Canada) Every month on the Third Thu, until Jan 20, 2022, 11 occurrence(s) Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Apr 15, 2021 07:00 PM May 20, 2021 07:00 PM Jun 17, 2021 07:00 PM Jul 15, 2021 07:00 PM Aug 19, 2021 07:00 PM Sep 16, 2021 07:00 PM Oct 21, 2021 07:00 PM Nov 18, 2021 07:00 PM Dec 16, 2021 07:00 PM Jan 20, 2022 07:00 PM Please download and import the following iCalendar (.ics) files to your calendar system. -

Biblioteca La Bòbila # 71

bobila.blogspot.com el fanzine del “Club de Lectura de Novel·la Negra” de la Biblioteca la Bòbila # 71 FI A vegades passa. Un autor està treballant en una afincat a Gijón i que durant anys els addictes a novel·la, i es mor. Resta una novel·la inacabada. lanSemana Negra de juliol haureu conegut com a Una feina a mig fer. organitzador i ma dreta de Paco Ignacio Taibo II. La proposta de lectura que us fem aquesta vegada En morir deixà inacabada la novel·la, que completà és la de tres exemples d’ “inacabats”. el també cubà Amir Valle. Enmig de la nit, de William Irish, era un manuscrit que va acabar Lawrence Block, bon coneixedor de l’obra d’Irish. L’exemple més conegut d’inacabats dins la novel·la negra és, potser, El misteri de Poodle Springs, de Raymond Chandler, que Robert B. Parker, bon coneixedor de la novel·la negra amb detectiu ─ell mateix ha fet la sèrie Spencer─, va reemprendre i acabar. També tenim un exemple més proper en El guardián de las esencias, de Justo Vasco, un cubà afincat a Gijón i que durant anys els addictes a la BIBLIOTECA LA BÒBILA L'Hospitalet / Esplugues L'H Confidencial 1 d’una noticia , un tiroteig per qüestions de droga al West Side”. O sigui que l’aportació de Block no supera les trenta pàgines, i a més se cenyeix a les intencions exhibides per Woolrich, cosa que duu a terme amb notable intel·ligència. En qualsevol cas, Enmig de la nit s’integra profundament en l’univers poètic i metafísic de les novel·les que van fer cèlebre la firma de William Irish i constitueix un descobriment d’importància palpable, estètica i històrica. -

Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, a Case Study

Katie Walsh Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, A Case Study Abstract William Powell became a star in the 1930s due to his unique brand of suave charm and witty humor—a quality that could only be expressed with the advent of sound film, and one that took him from mid-level player typecast as a villain, to one of the most popular romantic comedy leads of the era. His charm lay in the nonchalant sophistication that came naturally to Powell and that he displayed with ease both on screen and off. He was exemplary of the success of the new kind of star that came into their own during the transition to sound: sharp- or silver-tongued actors who were charming because of their way with words and not because of their silver screen faces. Powell also exercised a great deal of control over his publicity and star image, which is best examined during his short and failed tenure as a Warner Bros. during the advent of his rise to stardom. Despite holding a great amount of power in his billing and creative control, Powell was given a parade of cookie-cutter dangerous playboy roles, and the terms of his contract and salary were constantly in flux over the three years he spent there. With the help of his agent Myron Selznick, Powell was able to navigate between three studios in only a matter of a few years, in search of the perfect fit for his natural abilities as an actor. This experimentation with star image and publicity marked the period of the early 1930s in Hollywood, as studios dealt with the quickly evolving art and technological form, industrial and business practices, and a shifting cultural and moral landscape. -

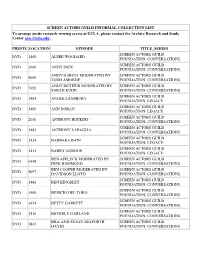

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS