On Nigerian and Indian Toponyms: Socio-Cultural Divergence and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday, 21St February, 2017

8TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION NO. 110 397 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 21st February, 2017 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 1. Report of the Committee on Trade and Investment Consumer Protection Act (Repeal & Re-enactment) Bill, 2017 (SB. 257) Sen. Fatima Raji-Rasaki (Ekiti Central) -That the Senate do receive the report of the Committee on Trade and Investment on the Consumer Protection Act (Repeal & Re-enactment) Bill, 2017 (SB. 257) – To be laid. 2. Report of the Committee on Works Federal Roads Maintenance Agency (Repeal & Re-enactment) Bill, 2017 (SB. 219) Sen. Kabiru Gaya (Kano South) -That the Senate do receive the report of the Committee on Works on the Federal Roads Authority Bill, 2017 (SB. 219) – To be laid. 3. Report of the Auditor General for the Federation Senate Leader -That the Senate do receive the report of the Auditor General for the Federation on the Accounts of the Federation of Nigeria for the year ended 31st December, 2015 Part 1 – To be laid. ORDERS OF THE DAY MOTIONS 1. The urgent need for the Federal Government to redeem Local Contractors Debts. Sponsor: Sen. Oluremi Tinubu (Lagos Central) Co-sponsors: Sen. Shehu Sani (Kaduna Central) Sen. Solomon O. Adeola (Lagos West) Sen. David Umaru (Niger East) Sen. Magnus Abe (Rivers East) Sen. Gbenga Ashafa (Lagos East) The senate: Notes that the Nigerian economy is experiencing difficult times caused by a slump in oil prices, with the result that a negative GDP (it shrank by 0.36% in the first quarter, 2.06% in the second quarter, and 2.24% in the third quarter) was recorded in three consecutive quarters of 2016. -

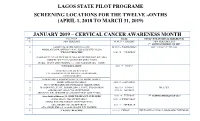

Lagos State Pilot Programe Screening Locations for the Twelve Months

LAGOS STATE PILOT PROGRAME SCREENING LOCATIONS FOR THE TWELVE MONTHS (APRIL 1, 2018 TO MARCH 31, 2019) JANUARY 2019 – CERVICAL CANCER AWARENESS MONTH S/N LOCATION DATE NOTES (FOR INTERNAL REFERENCE) 1. NEW YEAR DAY 01.01.19 – TUESDAY NEW YEAR DAY 2019 1ST #GIVINGTUESDAY OF 2019 2. LAGOS STATE FIRE SERVICE (LSFS) 02.01.19 – WEDNESSDAY B/D: “F.I.R.E” (1ST OF JAN) MOBOLAJI BANK ANTHONY WAY, IKEJA BUS STOP, IKEJA 3. *TWO OUTREACHES* 03.01.19 – THURSDAY IFAKO-IJAIYE LGA SECRETARIAT: NO 1 OLUWATOYIN ST, OFF AINA AJOBO ST, OFF YAYA ABATAN RD, OGBA- IJAIYE IFAKO – IJAIYE MINI STADIUM, 1/2, COLLEGE RD IFAKO – IJAIYE 4. *TWO LOCATIONS* 04.01.19 – FRIDAY OJOKORO LCDA SECRETARIAT 9/11, AGBADO STATION RD (IJAIYE OJOKORO RD), IJAIYE-OJOKORO ASIWAJU BOLA AHMED TINUBU ULTRA MODEL MARKET 5. OJODU LCDA SECRETARIAT: 05.01.19 – SATURDAY NO 1-3 SECRETARIAT RD, POWERLINE, OKEIRA, OGBA 6. IBA HOUSING ESTATE, BEHIND ZONE E FENCE, OTO-IJANIKIN 06.01.19 – SUNDAY THE EPIPH. 7. AGBADO/OKE-ODO LCDA SECRETARIAT: 07.01.19 – MONDAY ABEOKUTA E/W, OPPOSITE OJA-OBA BUS STOP, ABULE EGBA 8. mass medical mission | 31, BODE THOMAS ST, SURULERE 08.01.19 – TUESDAY 2ND #GIVINGTUESDAY OF 2019 9. AYOBO-IPAJA LCDA SECRETARIAT: 09.01.19-WEDNESDAY AYOBO-IPAJA RD, IGBOGILA BUS STOP, IPAJA 10. OTO-AWORI LCDA SECRETARIAT: 10.01.19 – THURSDAY OTO-AWORI, KM 28, LAGOS-BADAGRY E/W, IJANIKIN 11. *TWO OUTREACHES* 11.01.19 – FRIDAY THE TONYE COLE DAY (DIAMOND CENTURION) MAKOKO COMMUNITY INT’L THANK YOU DAY YABA LCDA SECRETARIAT: 198 H/MACAULAY ST, ADEKUNLE, YABA 12. -

Exxonmobil News Edition 2 2016

A publication of ExxonMobil affiliates in Nigeria ISSN 1597-0442 EDITION 2, 2016 ExxonMobil employees charged on safety & profitability LCM launches safety & profitability campaign Holds employee forum ExxonMobil partners FRSC for behavioral Giving back through Youth Road Safety Awareness Campaign Mentoring Program NEWS CONTENTS ExxonMobil News MPN supports ISSN: 1597-0442 10 construction of Women’s Breast Esso Exploration and Production Nigeria Limited (EEPNL) Care Facility Esso Exploration and Production Nigeria (Offshore East) Limited EEPNL commissions, Mobil Oil Nigeria Plc (MON) 12 hands over newly Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited (MPN) constructed Sick Bay Edition 2, 2016 COVER ExxonMobil employees charged on safety and Chairman Managing Director, EEPNL & MPN and profitability Lead Country Manager 14 Nolan A. O’Neal Chairman/Managing Director, MON Adetunji A. Oyebanji Director, Lubricants & Specialties, MON A. J. MacNaughton General Manager, Public & Government Affairs Paul C. Arinze Editors COMMUNITY RELATIONS Athletes in action at the Mobil Producing Nigeria (MPN) sponsored Oge Udeagha; Akin Fatunke EM Foundation athletics event at Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 16 supports “Road to Editorial Team Growth” Women Adeyemi Fakayejo; Ozemoya Okordion; Empowerment Ernest Omo-Ojo; Mfon Abia; NEWS MPN trains 200 Program Chukwuemeka Okonkwo; Patrick Utomi Athletes in Akwa 3 Ibom State NNPC/MPN Joint Cover/Concept/Graphic Design Venture trains 300 Taiwo Ogunbiyi 18 graduates on ICT, Registered Office Upstream Nigeria donates laptop to Mobil House, 1, Lekki Expressway, P.M.B 12054, honors employees all trainees 5 through Advanced Victoria Island, Lagos. Skill Milestone awards EM staff give back Published by Public & Government Affairs Department MPN trains 200 athletes in Akwa Ibom State through Youth for Employees of ExxonMobil subsidiaries in Nigeria. -

Entrenching Urban Parks in Green Infrastructure: a Study of Surulere Township in Metropolitan Lagos

Entrenching Urban Parks in Green Infrastructure: A Study of Surulere Township in Metropolitan Lagos Tunji Adejumo.Ph.D Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Lagos, Lagos. [email protected]; Tel 08034431439 ABSRACT The poor quality of Nigerian urban environment has been attributed partly to the inadequate, misuse and mismanagement of green infrastructure. It exerted major strain on the physical outlook of the cityscapes and a negative effect on the productivity of the residents. The paper examines practical strategies to increase park area on demographic basis in Surulere Local Government Area. The study is underpinned by green infrastructure principles. The paper recognised the importance of previous desktop studies in the metropolis and Surulere Local Government area especially demographic survey on community development area basis. Semi structured interviews of purposively chosen community leaders and questionnaires were used to comprehend urban parks needs of Surulere people. The study revealed that 327 hectares of planned open spaces currently exist in Surulere. 50% of the existing planned open spaces are privately owned while 45% and 5% are institutional and public spaces respectively. Further revelation shows that 1043 hectares of public park area is required to meet recreational demand of 1,184,000 people. Acquiring land to meet this deficit explored bioremediation of polluted wetlands and illegal refuse dumps. Besides absorbing the 1043 hectares deficit the suggested reclamation will provide much needed opportunity to turn these brown fields to green area in this season of climate change negative impacts. In the absence of city government and failure of Local Government in discharging the constitutional right of urban park provision, the paper recommended the need for constitutional review that will empower State Government to develop parks as green infrastructure hubs. -

Govt Seeks Temporary Waiver of Sports Ban Max 23º 150 Fils PAS Making ‘Serious and Relentless Efforts’ Min 11º

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, DECEMBER 24, 2016 RABI ALAWWAL 25, 1438 AH No: 17090 Municipality Hijackers of Heat retire destroys tons Libyan plane O’Neal’s of foul food2 surrender7 in Malta No.44 32 jersey Govt seeks temporary waiver of sports ban Max 23º 150 Fils PAS making ‘serious and relentless efforts’ Min 11º KUWAIT: The government yesterday called on FIFA and the International Olympic Committee to temporarily lift a 14-month sports ban while it amends a controversial law. The Public Authority for Sports (PAS) urged football’s gov- erning body and the IOC to “lift the ban on Kuwaiti sports activities tem- porarily until relevant local laws are revised”. World sports bodies led by FIFA and the IOC suspended Kuwait in October last year for the second time since 2010 over alleged government meddling in sports. The suspension was due to legisla- tion over recent years that allowed the government to interfere in local sports federations and undermine their independence. In a statement yesterday published by the official KUNA news agency, Kuwait’s sports authority said it was making “serious and relentless efforts” to have the ban lifted. It said the National Assembly would set up a panel on Tuesday next week to draft amendments to the relevant laws. Kuwait is hoping to compete in the qualifiers for the 2019 AFC Asian Cup, it said. —AFP Iraq recovers stolen ancient Italian police and forensics experts stand by the body of suspected Berlin truck attacker Anis Amri after he was shot dead in Milan early yesterday. Kuwaiti relic (Inset) An image grab taken from an Islamic State propaganda video shows Amri pledging allegiance to IS on the Kieler Bruecke, a Berlin bridge. -

Lagos State Government Public Procurement

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLIC PROCUREMENT AGENCY LETTERS OF AWARD REGISTERED/ AWARDS DUE TO CONTRACTOR'S REGISTRATION STATUS - MAY 2018 MDA PROJECT DESCRIPTION AMOUNT N CONTRACTOR CLASS DATE OF ISSUE OF S/N LETTER OF AWARD FROM MDA 1 Office of Chief Payment of Management Services of 95,768,750.00 Carverton Marine Ltd D 25/01/2018 of Staff Touring Boat 40 and Majesty 43 Fly Boat 2 Ministry of Completion of 850M Road Length and 25,804,600.15 Nisatron Limited C 24/4/2018 Housing Car Parks at LAGOSHOMS Ilupeju (Car Parks and Walkway) 3 Ministry of Construction of Phase 1 of the 32 2,983,928,780.73 CIBA Construction Company E 17/4/2018 Agriculture Tonnes Per Hour Rice Mill at Imota Limited 4 Ministry of Construction of Imota Light Industrial 2,419,939,855.32 CIBA Construction Company E 25/4/2018 Commerce Park Limited Industry and Cooperatives 5 Ministry of 4th Quarter (Oct- Dec) Proposal on 15,000,000.00 Hedge of God Ventures B 23/4/2018 Information Public Affairs and Policy Consultancy Limited and Strategy 6 Ministry of Procurement of items for Integrated 10,560,000.00 Healthline Global Services B 25/4/2018 Health Community Outreach for "Save one Limited Million Lives" (SOML) 7 Ministry of Implementation of "V" block 32,181,300.00 Rack Centre Limited B 30/4/2018 Science and infrastructure at Rack Centre Technology 8 Lagos State Renovation Works at Lagos State 116,662,286.85 Edviv Designs Associates C 04-04-18 Infrastructure University Teaching Hospital Asset (LASUTH), Ikeja Management Agency 9 Lagos State Procurement of Twelve (12) FG Wilson 61,740,000.00 Tigle Nigeria Limited C 05-07-18 Judiciary Perkins P25 30KVAGenerators For Magistrate Courts 10 Lagos State Procurement of Two (2) FG Wilson P 25,356,158.33 Tigle Nigeria Limited C 05-07-18 Judiciary 165-1 150 KVA Generators For The Official Residence of The Hon. -

2020-Lagos-Budget.Pdf

Citizens' Guide to 2020 BUDGET Lagos state Government Lagos State Budget Objectives of the 2020 Budget The 1999 Constitution, section 121 stipulates The objectives of Y2020 budget include: that prior to the commencement of each financial year; the Governor require to present Attract private sector investments to the State an annual Budget (Appropriation Bill) of the economy by creating an enabling environment; State to the House of Assembly for enactment Aggressively develop, upgrade and maintain our into law. Infrastructure; Thereafter, the Governor assents to it, then Invest in human capital development, i.e. becomes an Appropriation Law. This therefore, education and healthcare; puts the responsibility of the Budget between the Executive and Legislative arm of the Facilitate sustainable social investment and Government. enterprise; Improve capacity to collect due revenues as Y2020 Budget (''Budget of Awakening'') was efficiently as possible; presented to the Lagos State House of Assembly on Friday, 8 November, Y2019 and was passed Improve civic participation in governance, and into Law on 30th December, 2019. Mr. Governor, automate public services and engagement; Babajide Sanwoolu gave his assent to it on 31st December, 2019. Build impactful partnerships with the Federal Government, other States, development partners and civil society; and Improve the quality of the environment and our public spaces generally. 01 Lagos Demographics Population Growth Population density Projected Population 7,390 27,281,339 3.20% person / km² Total Mass -

Promoting Sport Participation Amongst the Disabled in Nigeria As a Vehicle to Fostering Their Inclusion and Well Being

A means to an end: Promoting sport participation amongst the disabled in Nigeria as a vehicle to fostering their inclusion and well being A Research Paper presented by: UGOCHI OSUOJI NIGERIA in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Economics of Development (ECD) Members of the Examining Committee: Dr. Kees Bierkart Dr. Robert Sparrow The Hague, The Netherlands December 2019 ii Contents List of Tables v List of Figures v List of Acronyms v Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Relevance to Development Studies viii Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Problem Statement 4 1.2 Justification of the study 5 1.3 Definition of terms 6 1.4 Research objectives and question 7 1.4.1 Main research question 8 1.4.2 Sub Questions: 8 1.5 Methodology 8 1.5.1 Techniques for data generation 9 1.5.2 Choice of research location 10 1.5.3 Selection of Respondents 10 1.5.4 Limitations and Scope of Study 11 1.5.5 Ethical Consideration 12 1.6 Chapter summary 13 Chapter 2 - Literature review and Theoretical framework 14 2.1 Introduction 14 2.2 Models of disability 14 2.2.1 The charity model 14 2.2.2 The human rights model 16 2.2.3 The medical model 16 2.2.4 The social model 18 2.3 Linking sports and social inclusion 20 2.4 Sport as an instrument for physical and social well being 21 2.5 Conceptualising disability 23 2.6 The ‘Development through Sports’ Theory of Change Framework 23 2.7 The International Classification of functioning (ICF) Framework 25 2.8 Chapter Summary 27 Chapter 3: Disability in -

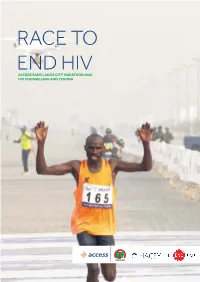

Access Lagos Marathon HIV 2020 Report Updated

RACE TO ACCESS BANK LAGOS CITY MARATHON 2020 ENDHIV COUNSELLING AND TESTINGHIV A RACE AGAINST HIV ACCESS MARATHON 2020 ACCESS BANK LAGOS CITY MARATHON 2020 HIV COUNSELLING AND TESTING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Nigeria had the second-largest HIV epidemic in the world and one of the highest rates of new infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Many people living with HIV in Nigeria are also unaware of their status. In 2018 an estimated 1.9 million people were living with HIV in Nigeria, with only 67% of them aware of their status (UNAIDS, 2019). According to the National HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey (NAIIS), there is some progress in ending HIV in Nigeria; HIV prevalence reduced nationally from 2.8% in 2017 to 1.4% in 2018, and HIV counselling and testing sites and treat- ment sites have increased. However, there is also an increase in the number of new cases, particularly among young people, especially girls aged 20-24. Factors that have in�uenced increased HIV vulnerability among young people include lack of adequate knowledge on HIV, poor access to sexual and reproductive health information, early sexual debut amongst others. HIV counselling and testing is the gateway to care, treatment and support for persons in need. It gives those who are negative the opportunity to change behaviours that may put them at risk of the infection in future, and it links those who are positive to care. Unfortunately, there are still many barriers to testing for HIV, including fear, discrimination, stigmati- sation and issues with con�dentiality. To overcome this, we increase discussion on and provision of HIV testing. -

Lagos State of Nigeria Lagos State House of Assembly

LAGOS STATE OF NIGERIA No. 94 SEVENTH ASSEMBLY 502 Second Session 2012/2013 LAGOS STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 31st October, 2012 S/No. Names Constituencies The House met at 10.40 a.m. Mr. Speaker read prayers. Present. 1. Hon. Ikuforiji A.S. Ikeja I 2. “ Kolawole T.M. Ajeromi/Ifelodun I 3. “ Dr. Adeyeye A.J. Kosofe II 4. “ Dr. Balogun A.M. Surulere II 5. “ Mrs. Akande L.F. Ikeja II 6. “ Abiru R.L. Somolu II 7. “ Ogundimu O. Agege II 8. “ Balogun O.A.A. Ajeromi/Ifelodun II 9. “ Yusuf B. Alimosho I 10. “ Adeniji-Adele S. Amuwo/Odofin I 11. “ Mrs. Akinlola-Hassan R. Amuwo/Odofin II 12. “ Jimoh O. Apapa II 13. “ Layode I.O. Badagry I 14. “ Avoseh H.S. Badagry II 15. “ Tobun A. Epe I 16. “ Olulade S. Epe II 17. “ Alimi K.A. Eti-Osa I 18. “ Yishawu O.G. Eti-Osa II 19. “ Mojeed A. Fatai Ibeju/Lekki I 20. “ Kazeem Raheem Adewale Ibeju/Lekki II 21. “ Fafunmi O.S. Ifako/Ijaiye I 22. “ Agunbiade S.O.B. Ikorodu I 23. “ Mrs. Akinsola A. Ikorodu II 24. “ Osinowo S.A. Kosofe I 25. “ Masha H.A. Lagos Island I 26. “ Alawiye-King W. Lagos Island II 27. “ Oloto B. Lagos Mainland I 28. “ Oshun M.O. Lagos Mainland II 29. “ Ayinla B.Y. Mushin II 30. “ Ogunyemi L. Ojo II 31. “ Ayeni L.B. Oshodi/Isolo I 32. “ Mrs. Olatunji-Edet O. Oshodi/Isolo II 33. “ Olowo R.E. Somolu I 34. “ Lawal K.O. -

Hypertension in Surulere: a Community Survey

Research article Blood Res Transfus J Volume 1 Issue 2 - May 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ademolu Adegbenga Bolanle DOI: 10.19080/OABTJ.2017.01.555558 Hypertension in Surulere: A Community Survey Ademolu Adegbenga Bolanle1*, Ademolu Abiola2, Ogunleye OO1, Onyekwere C1, Ogbera AO1 and Oke D1 1Department of medicine, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria 2Department of Paediatrics, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria Submission: April 24, 2017; Published: May 05, 2017 *Corresponding author: Ademolu Adegbenga Bolanle, Department of medicine, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria, Tel: ; Email: Abstract Objective: The cure for hypertension remains a global challenge. In the past numerous surveys had been conducted to determine the prevalence of hypertension in different settings but unfortunately these surveys are mostly done in developed countries.. The present pilot study evaluated the prevalence of hypertension in an urban area in patients living in a resource poor country in Africa. Methods: The blood pressure of 72 participants was measured using a mercurial sphygmomanometer at heart level in the community setting. The study location was Surulere in Lagos Nigeria in a small community with access to health care delivery at primary, secondary and tertiary level. Results: A total of 72 participants were screened in our pilot study. The age range was from 18-88 years. 51.39% (37 participants) were hypertensive.24.32% of the hypertensive were male while 75.67% were females. Hence the male to female ratio (M:F) amongst hypertensive patients was 1:3. In this study population the age range of the hypertensive patient that are male was 37-70 years with mean age of 57. -

African Football Film Festival (AFFF) | Lagos, Nigeria | 11 to 13 July 2014

3rd African Football Film Festival (AFFF) Theme: “The State of African Football“ Lagos | Nigeria · 20 – 30 April 2017 3rd African Football Film Festival (AFFF) | 20 – 30 April 2017 | p 2 – background Football, film and festivity for the community Emotions, passion, AFFF 2017 – asymmetry and agony of African football drama, even tragedy – football and film have … because AFFF offers much more than opportunities for relaxation – so much in common! in 2017 the festival will focus on “The State of African Football“. And from time to time Unlike the football industry, a dream factory producing perfect pictures, they mesh together! AFFF tells true stories about challenges and pitfalls of the “beautiful game“ like corruption, discrimination, racism or trafficking of players. The first ever African Football Film Festival Especially African football faces asymmetric realities: On the one hand (AFFF) in Lagos was agents and officials cash in on talents and some few stars reach to the born out of the desire top. On the other foot grassroots, amateur and professional football are to combine sporting far behind in terms of equipment, facilities, methodology, results … festivity with cultural and social issues that The third edition of AFFF from 20 – 30 April 2017 will bring together are important to many footballers, administrators, sports journalists and the general public to young Africans today ... discuss these challenges while enjoying top-class football films. 3rd African Football Film Festival (AFFF) | 20 – 30 April 2017 | p 3 – programme For