Protecting Wetlands with Redundant Drainage Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action Statement No.134

Action statement No.134 Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Yarra Pygmy Perch Nannoperca obscura © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Cover photo: Tarmo Raadik Compiled by: Daniel Stoessel ISBN: 978-1-74146-670-6 (pdf) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone the DELWP Customer Service Centre on 136 186, email [email protected], or via the National Relay Service on 133 677, email www.relayservice.com.au. This document is also available on the internet at www.delwp.vic.gov.au Action Statement No. 134 Yarra Pygmy Perch Nannoperca obscura Description The Yarra Pygmy Perch (Nannoperca obscura) fragmented and characterised by moderate levels is a small perch-like member of the family of genetic differentiation between sites, implying Percichthyidae that attains a total length of 75 mm poor dispersal ability (Hammer et al. -

Final St. Andrew Bay Characterization

1004401.0003.04 Draft St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization December 2016 Prepared by: St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT This document was developed in support of the Surface Water Improvement and Management Program with funding assistance from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund. ii St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT Version History Location(s) in Date Version Summary of Revision(s) Document 6/28/2016 1 All Initial draft Watershed Characterization (Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) submitted to NWFWMD. 7/14/2016 2 Throughout Numerous edits and comments from District staff 11/18/2016 3 Throughout Numerous revisions to address District comments. 11/23/2016 4 Throughout Numerous edits and comments from District staff 12/5/2016 5 Throughout Numerous revisions to address District comments. L:\Publications\4200-4499\4401-0001_NWFWD iii St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT This page intentionally left blank. iv St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT Table of Contents Section Page 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 SWIM Program Background, Goals, and Objectives...........................................1 -

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

Which Feature, Place Or View Is Significant, Scenic Or Beautiful And

DPCD South West Victoria Landscape Assessment Study | CONSULTATION & COMMUNITY VALUES Landscape Significance Significant features identified were: Other features identified outside the study area were: ▪ Mount Leura and Mount Sugarloaf, outstanding ▪ Lake Gnotuk & Lake Bullen Merri, “twin” lakes, near volcanic features the study area’s edge, outstanding volcanic features Which feature, place or view is ▪ Mount Elephant of natural beauty, especially viewed from the saddle significant, scenic or beautiful and ▪ Western District Lakes, including Lake Terangpom of land separating them why? and Lake Bookar ▪ Port Campbell’s headland and port Back Creek at Tarrone, a natural waterway ...Lake Gnotuk and the Leura maar are just two examples of ▪ Where would you take a visitor to the outstanding volcanic features of the Western District. They give great pleasure to locals and visitors alike... show them the best view of the Excerpt from Keith Staff’s submission landscape? ▪ Glenelg River, a heritage river which is “pretty much unspoilt” ▪ Lake Bunijon, “nestled between the Grampians and rich farmland in the west, the marsh grasses frame the lake as a native bird life sanctuary” ▪ Botanic gardens throughout the district which contain “weird and wonderful specimens” ▪ Wildflowers at the Grampians The Volcanic Edge Booklet: The Mt Leura & Mt Sugarloaf Reserves, Camperdown, provided by Graham Arkinstall The Age article from 1966 about saving Mount Sugarloaf Lake Terangpom Provided by Brigid Cole-Adams Photo provided by Stuart McCallum, Friends of Bannockburn Bush, Greening Australia 10 © 2013 DPCD South West Victoria Landscape Assessment Study | CONSULTATION & COMMUNITY VALUES Other significant places that were identified were: Significant views identified were: ▪ Ditchfield Road, Raglan, an unsealed road through ▪ Views generally in the south west region ▪ Views from summits of volcanic craters bushland .. -

Corangamite Catchment Management Authority Area

Victorian Water Quality Monitoring Network Trend Analysis Corangamite Catchment Management Authority Area Produced for the Department of Natural Resources and Environment by Sinclair Knight Merz Victorian Water Quality Monitoring Network Trend Analysis Corangamite Catchment Management Authority Area Other reports in this series: Victorian Statewide Summary East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority Area Glenelg Catchment Management Authority Area Goulburn Catchment Management Authority Area Mallee Catchment Management Authority Area North Central Catchment Management Authority Area North East Catchment Management Authority Area Port Phillip Catchment Management Authority Area West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority Area Wimmera Catchment Management Authority Area Prepared by W.E. Smith and R.J. Nathan Sinclair Knight Merz Executive Summary The Victorian Water Quality Monitoring Network (VWQMN) consists of around 280 stations located throughout Victoria. A range of water quality indicators are measured at these sites and data has been measured for up to 25 years at approximately monthly intervals. While this data set represents a substantial body of information, to date there has been no systematic and consistent analysis of the data that provides an assessment of the temporal and spatial variation of the indicators. Such analysis can provide valuable information regarding the impacts of past management practices on catchment processes, the impact of land management practices and interventions, and the likely direction of future water quality changes. The scope of this report is to present the nature and significance of time trends in water quality data recorded at VWQMN sites within the region controlled by the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. Only stations with records greater than ten years were used, and the indicators considered were pH, turbidity, electrical conductivity (EC), total phosphorus and total nitrogen. -

DUCK HUNTING in VICTORIA 2020 Background

DUCK HUNTING IN VICTORIA 2020 Background The Wildlife (Game) Regulations 2012 provide for an annual duck season running from 3rd Saturday in March until the 2nd Monday in June in each year (80 days in 2020) and a 10 bird bag limit. Section 86 of the Wildlife Act 1975 enables the responsible Ministers to vary these arrangements. The Game Management Authority (GMA) is an independent statutory authority responsible for the regulation of game hunting in Victoria. Part of their statutory function is to make recommendations to the relevant Ministers (Agriculture and Environment) in relation to open and closed seasons, bag limits and declaring public and private land open or closed for hunting. A number of factors are reviewed each year to ensure duck hunting remains sustainable, including current and predicted environmental conditions such as habitat extent and duck population distribution, abundance and breeding. This review however, overlooks several reports and assessments which are intended for use in managing game and hunting which would offer a more complete picture of habitat, population, abundance and breeding, we will attempt to summarise some of these in this submission, these include: • 2019-20 Annual Waterfowl Quota Report to the Game Licensing Unit, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries • Assessment of Waterfowl Abundance and Wetland Condition in South- Eastern Australia, South Australian Department for Environment and Water • Victorian Summer waterbird Count, 2019, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research As a key stakeholder representing 17,8011 members, Field & Game Australia Inc. (FGA) has been invited by GMA to participate in the Stakeholder Meeting and provide information to assist GMA brief the relevant Ministers, FGA thanks GMA for this opportunity. -

Sampling and Analysis of Lakes in the Corangamite CMA Region (2)

Sampling and analysis of lakes in the Corangamite CMA region (2) Report to the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority CCMA Project WLE/42-009: Client Report 4 Annette Barton, Andrew Herczeg, Jim Cox and Peter Dahlhaus CSIRO Land and Water Science Report xx/06 December 2006 Copyright and Disclaimer © 2006 CSIRO & Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO Land and Water or the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. Important Disclaimer: CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. From CSIRO Land and Water Description: Rocks encrusted with salt crystals in hyper-saline Lake Weering. Photographer: Annette Barton © 2006 CSIRO ISSN: 1446-6171 Report Title Sampling and analysis of the lakes of the Corangamite CMA region Authors Dr Annette Barton 1, 2 Dr Andy Herczeg 1, 2 Dr Jim Cox 1, 2 Mr Peter Dahlhaus 3, 4 Affiliations/Misc 1. -

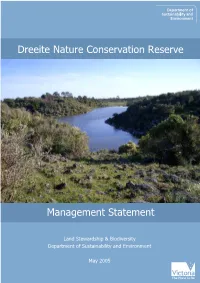

Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve Management Statement

Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve Management Statement Land Stewardship & Biodiversity Department of Sustainability and Environment May 2005 This Management Statement has been written by Hugh Robertson and James Fitzsimons for the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. This Statement fulfils obligations by the State of Victoria to the Commonwealth of Australia, which provided financial assistance for the purchase of this reserve under the National Reserve System program of the Natural Heritage Trust. ©The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2005 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. ISBN 1 74152 140 8 Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Cover: Permanent wetland surrounded by Stony Knoll Shrubland, Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve (Photo: James Fitzsimons). Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve Objectives This Management Statement for the Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve outlines the reserve’s natural values and the directions for its management in the short to long term. The overall operational management objective is: Maintain, and enhance where appropriate, the condition of the reserve while allowing natural processes of regeneration, disturbance and succession to occur and actively initiating these processes where required. Background and Context Reason for purchase Since the implementation of the National Reserve System Program (NRS) in 1992, all Australian states and territories have been working toward the development of a comprehensive, adequate and representative (CAR) system of protected areas. -

Development of a SWAT Model in the Yarra River Catchment

20th International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Adelaide, Australia, 1–6 December 2013 www.mssanz.org.au/modsim2013 Development of a SWAT model in the Yarra River catchment S.K. Dasa, A.W.M. Nga and B.J.C. Pereraa a College of Engineering and Science, Victoria University, Melbourne 14428, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract: The degradation of river water quality in Victorian agricultural catchments is of concern. Physics-based models are useful analysis tools to understand diffuse pollution and find solutions through best management practices. However, because of high data requirements and processing, use of these models is limited in many data-poor catchments; for example the Australian catchments where water quality and land use management data are very sparse. Recently, with the advent of computationally efficient computers and GIS software, physics-based models are increasingly being called upon in data-poor regions. SWAT is a promising model for long-term continuous simulations in predominantly agricultural catchments. Limited application of SWAT has been found in Australia for modeling hydrology only. Adoption of SWAT as a tool for predicting land use change impacts on water quality in the Yarra River catchment, Victoria (Australia) is currently being considered. The objective of this paper is to evaluate hydrological behaviour of SWAT model in the agricultural part of the Yarra River catchment for 1990-2008 periods. The SWAT model requires the following data: digital elevation model (DEM), land use, soil, land use management and daily climate data for driving the model, and streamflow and water quality data for calibrating the model. -

Scientific Investigation Into Eel Deaths in Western Victoria

SCIENTIFIC REPORT SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION INTO EEL DEATHS IN WESTERN VICTORIA PAUL LEAHY, RENEE PATTEN, ALEX LEONARD Publication 1173 December 2007 SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION INTO EEL DEATHS IN WESTERN VICTORIA SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION INTO EEL DEATHS IN WESTERN VICTORIA EPA Victoria 40 City Road, Southbank Victoria 3006 AUSTRALIA PAUL LEAHY, RENEE PATTEN, ALEX LEONARD December 2007 Publication 1173 ISBN 0 7306 7666 8 © EPA Victoria 2007 2 SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION INTO EEL DEATHS IN WESTERN VICTORIA TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 6 2. METHODS ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Site location and description......................................................................................................................... 9 Collection of in-situ water parameters.......................................................................................................... 9 Chemical analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 11 Algal analysis................................................................................................................................................ -

1 Index to Victorian Landcare and Catchment Management, Nos. 1

Index to Victorian Landcare and Catchment Management, Nos. 1–68 ABC Radio National’s Bush Telegraph program, seeks regional people for its ‘Country Viewpoint’ segment 31.19 Abbottsmith Youl, Tom, wins DEDJTR Innovation in Sustainable Farm Practices Award – Goulburn Broken 65.17, 65.23 Aboriginal Australians see Indigenous headings Aboriginal Landcare Facilitator Cultural Insight Training Day, Benalla 66.22 role 63.14, 65.22 absentee landholders attracting to Landcare 40.12–13, 60.7 Landcare-aid, Goulburn Broken CMA 24.18 purchasing rural properties 40.12–13 Adair, Robin, New bio control for boneseed 9.13 Adams, Margaret, Miners Rest Landcare Group changes wasteland to wetland 41.21 Adams family, Lower Hopkins River properties 38.18 Adamson’s blown grass, endangered species 15.22 Adlam, Lauren, Woodend Trees for Mum, Mother’s Day event 55.18 Adult Multicultural Education Services (AMES) 55.4 aerial video technique, for crop and Landcare use 2.8–9 African feather grass, removal, along Glenelg River 36.17 African Landcare Network (ALN) conference, Mafikeng 56.9 African nationals, participation in Master TreeGrower course 56.17 African weed orchid, control 66.14–15 Agg, Cathie, Greenfleet – simple, ingenious and successful 28.20–21 agroforestry see farm forestry Agroforestry Expo ‘99 13.6 Agrostis adamsonii 15.22 Ainsworth, Justin and Melissa, win DPI Sustainable Farming Award – West Gippsland 47.16 Ainsworth, Melissa, Group leader, Merriman Creek Landcare Group 67.10 Ainsworth, Nigel, Herbicide advice for environmental weeds 18.8 Aire River, -

Corangamite Heritage Study Stage 2 Volume 3 Reviewed

CORANGAMITE HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 2 VOLUME 3 REVIEWED AND REVISED THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Prepared for Corangamite Shire Council Samantha Westbrooke Ray Tonkin 13 Richards Street 179 Spensley St Coburg 3058 Clifton Hill 3068 ph 03 9354 3451 ph 03 9029 3687 mob 0417 537 413 mob 0408 313 721 [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION This report comprises Volume 3 of the Corangamite Heritage Study (Stage 2) 2013 (the Study). The purpose of the Study is to complete the identification, assessment and documentation of places of post-contact cultural significance within Corangamite Shire, excluding the town of Camperdown (the study area) and to make recommendations for their future conservation. This volume contains the Reviewed and Revised Thematic Environmental History. It should be read in conjunction with Volumes 1 & 2 of the Study, which contain the following: • Volume 1. Overview, Methodology & Recommendations • Volume 2. Citations for Precincts, Individual Places and Cultural Landscapes This document was reviewed and revised by Ray Tonkin and Samantha Westbrooke in July 2013 as part of the completion of the Corangamite Heritage Study, Stage 2. This was a task required by the brief for the Stage 2 study and was designed to ensure that the findings of the Stage 2 study were incorporated into the final version of the Thematic Environmental History. The revision largely amounts to the addition of material to supplement certain themes and the addition of further examples of places that illustrate those themes. There has also been a significant re-formatting of the document. Most of the original version was presented in a landscape format.