222 Broadway Hotel Fort Garry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Matthias' Anglican Church

St.Matthias? Anglican Church The nave, looking toward the choir Photo: Bergeron Gagnon inc. Photo: Bergeron Gagnon inc. THE VALUE STATEMENT ST. MATTHIAS' ANGLICAN CHURCH CIVIC ADDRESS HERITAGE DESIGNATION RELIGIOUS DENOMINATION 10 Church Hill, Westmount Municipal - Category 1: Important Anglican (SPAIP) Provincial - None Federal - None OVERVIEW OF THE VALUE STATEMENT Historical Value The historical heritage value resides in the long history of the St. Matthias? Anglican Church with the development of Westmount. Its site has been continuously occupied by this religious denomination since 1874, when a mission chapel was established on a portion of the Forden Estate. The present church dates from 1912 and the parish hall from 1936. The association of the church with its immediate neighbourhood is embedded in the name chosen for the adjacent street, Church Hill. The sacrifice of the church membership during both World Wars is commemorated in the Memorial Chapel. Contextual Value The contextual heritage value resides in the church?s commanding presence on the corner of Cote St. Antoine and Church Hill. At the same time, the multiple entrances allow the complex to be easily accessed from both streets. Its institutional size and character make it a landmark within the surrounding residential fabric and connects it as well to the neighbouring institutions. Although its site is now almost entirely built up, the remaining church land is densely planted with shrubbery and mature trees. Architectural and Aesthetic Value The architectural and aesthetic heritage value resides in the skilful rendering of the neo-Gothic style, the excellent functional design, the ornamentation enhanced by the complex massing, the craftsmanship and the simple, noble materials used throughout both the exterior and interior of the complex. -

Downtown Old St. Boniface

Oseredok DISRAELI FWY Heaton Av Chinese GardensJames Av Red River Chinatown Ukrainian George A Hotels Indoor Walkway System: Parking Lot Parkade W College Gomez illiam A Gate Cultural Centre Museums/Historic Structures Main Underground Manitoba Sports Argyle St aterfront Dr River Spirit Water Bus Canada Games Edwin St v Civic/Educational/Office Buildings Downtown Winnipeg & Old St. Boniface v Hall of Fame W Sport for Life Graham Skywalk Notre Dame Av Cumberland A Bannatyne A Centre Galt Av i H Services Harriet St Ellen St Heartland City Hall Alexander Av Shopping Neighbourhoods Portage Skywalk Manitoba Lily St Gertie St International Duncan St Museum Malls/Dept. Stores/Marketplaces St. Mary Skywalk Post Office English School Council Main St The v v Centennial Tom Hendry P Venues/Theatres Bldg acific A Currency N Frances St McDermot A Concert Hall Theatre 500 v Province-Wide Arteries 100 Pantages Building Entrances Pharmacy 300 Old Market v Playhouse Car Rental Square Theatre Amy St Walking/Cycling Trails Adelaide St Dagmar St 100 Mere Alexander Dock City Route Numbers Theatre James A Transit Only Spence St Hotel Princess St (closed) Artspace Exchange Elgin Av aterfront Dr Balmoral St v Hargrave St District BIZ The DistrictMarket A W Cinematheque John Hirsch Scale approx. Exchange 200 John Hirsch Pl Notre Dame A Theatre v Fort Gibraltar 100 0 100 200 m Carlton St Bertha St and Maison Edmonton St National Historic Site Sargent Av Central District du Bourgeois K Mariaggi’s Rorie St ennedy St King St Park v 10 Theme Suite Towne Bannatyne -

October 2017

DELIVERING BUSINESS ESSENTIALS TO NTA MEMBERS OCTOBER 2017 MUSIC DESTINATIONS PAGE 25 NASHVILLE: EVERYBODY PLAYS PAGE 29 Noted! GUIDE TO THEATERS, PERFORMANCE VENUES PAGE 41 TWO TAKES ON CANADA PAGE 21 TRAVEL EXCHANGE BFFS PAGE 56 Songwriters at Nashville’s Bluebird Café THE VOICE MUST BE HEARD An Unforgettable New York Experience Don’t miss extraordinary Met productions, including such classics as Turandot, La Bohème, Madama Butterfl y, and The Magic Flute. Tickets start at $25 metopera.org Photo: Jonathan Tichler/Metropolitan Opera October 2017 JACOBSPILLOW.ORG Not your typical barn dance: Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival takes place each summer in western Massachusetts’ Berkshires region. This celebration of dance and movement includes hundreds of free performances and master classes that showcase the talents of world-class performers. Turn to page 37 to read about the event, as well as other tour options in the New England states. Features 21 25 29 Two takes on Canada Move to the music City Spotlight: Nashville Courier’s Gabe Webb and Pat Henderson Travelers journey to destinations across Visitors to this Tennessee town have as offer their thoughts on their respective the U.S. to experience the music they much fun with music’s past as they do recent trips to Ottawa and Winnipeg. love; see what’s there to greet them. with its present—and presence. Compass 34 Great Plains 37 New England 40 China A heap of history in North Dakota All about the arts in the Berkshires On the UNESCO trail in Beijing Good things in the Badlands Seafood tops -

TORRIVENT Has Amazing Versatility for ALL HEATING

TORRIVENT has amaz ing versatility FOR ALL HEATING AND VENTILATING NEEDS H ere's today's most adaptable large CHECK THESE TORRIVENT FEATURES : capacity universal heating and ventilating e QUIETER OPERATION -New, high-efficiency TRANE unit-the TRANE TORRIVENT! This Fans have low outlet velocities for whisper-quiet versatile unit is especially designed to pro operation. e MORE VERSATILE- Torrivent units heat, filter, clean vide maximum heat transfer for large air any combination of recirculated and outside air to capacities in all types of buildings . meet heating-ventilating requirements for buildings of every size and type. May be installed with or commercial, institutional and industrial. without duct work on floor, wall or ceiling. TORRIVENTcan be used for free delivery e MORE FLEXIBLE-Complete range of coil types and or for discharge into ductwork. Many sizes to meet every need. casings are available, with damper ar e WIDER RANGE- Nine sizes- 1, 2 or 3 fan models. rangements and discharge provisions e LONGER LIFE-Casing is of uniframe construction. Fan shafts are solid (not hollow), large diameter for to suit any job. minimum vibration. Fan bearings are mounted ex Ask your TRANE ternally for easy maintenance. Representat ive e LOWER COST-Greater coil and fan efficiency and multiple coil choice permit selection of equipment about TORRI that meets requirements exactly. No wasted VENT .. or write capacity! today for the de Branch Offices in all principal Cities tailed Technical Bulletin. Manufacturers of Equipment for Air Conditioning, Heating, TR-5723-R Ventilating. COMPANY OF CANADA LIMITED, TORONTO 14 OCTOBER, 1959 Seria l No 410, Vol. -

Take a Walk Through Time with Fairmont Hotels & Resorts

FAIRMONT HOTELS & RESORTS TAKE A WALK THROUGH TIME WITH FAIRMONT HOTELS & RESORTS For more than a century, our hotels have been at the heart of it all, serving as places of occasion for their communities. The exhilarating events, memorable meetings, and defining moments that have taken place within our hallowed halls are fascinating and countless. A look at some of the more notable ones: 1885 Bermuda's The Fairmont Hamilton Princess opens its doors, making it the oldest hotel in the Fairmont collection. 1888 Canada's first grand railway hotel, The Fairmont Banff Springs opens, bringing to life the vision of General Manager and soon-to-be President of Canadian Pacific Railway, Sir Cornelius Van Horne. It’s not all joy though, as Van Horne is furious to discover initial hotel plans give the kitchen the magnificent views of the Bow Valley. A rotunda is soon built to give the view back to the guests. 1889 Britain's first luxury hotel, The Savoy, opens and pioneers a number of “firsts” for hotels, including “ascending rooms” (electric lifts), 24-hour room service through a “speaking tube” connected to the restaurant, and its own laundry service and postal address. 1890's Silver baron James Graham Fair purchases the land where Fairmont's namesake San Francisco hotel now resides, hoping to build a family estate. His daughters begin planning on “The Fairmont” as a posthumous monument. “Fairmont” combines the name of the hotel’s founding family with its exclusive location atop Nob Hill. 1890 Society hostess Lady de Grey gathers a group of female contemporaries to dine at London’s The Savoy, a strike for equality, making it socially acceptable for women to gather for meals in public without their husbands, and inspiring generations of ladies-who-lunch. -

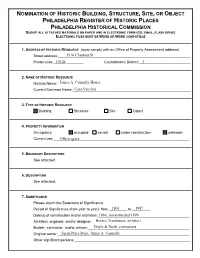

View Nomination

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3910 Chestnut St ________ Postal code:_______________19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________James A. Connelly House ________ Current/Common Name:________Casa Vecchia___________________________________________ ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________Office space ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1806 to _________1987 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1866; reconstructed 1896 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________Horace Trumbauer, architect _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________Doyle & Doak, contractors _________ Original -

Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA)

APPENDIX M Heritage Impact Assessment – Union Station Trainshed Heritage impact assessment Union Station Trainshed GO Rail Network Electrification Project Environmental Assessment Project # 14-087-18 Prepared by GS/JN PREPARED FOR: Rodney Yee, Project Coordinator Environmental Programs & Assessment Metrolinx 20 Bay Street Toronto, ON M5J 2W3 416-202-4516 [email protected] PREPARED BY: ERA Architects Inc. 10 St. Mary Street, Suite 801 Toronto, ON M4Y 1P9 416-963-4497 Issued: 2017-01-16 Reissued: 2017-09-18 Cover Image: Union Station Trainshed, 1930. Source: Toronto Archives CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Scope of the Report 1.2 Property Description 1.3 Site History 2 Methodology 11 2.1 Summary of Related Policy/Legislation/Guidelines 2.2 Material Reviewed 2.3 Date of Site Visit 3 Discussion of Cultural Heritage Value and Status 14 3.1 Discussion of Cultural Heritage Value 3.2 Statement of Cultural Heritage Value 3.3 Heritage Recognition 4 Site conditions 20 4.1 Current Conditions 5 Discussion of the Proposed Intervention 25 5.1 Description of Proposed Interventions 5.2 Impact Assessment 5.3 Mitigation Strategies 6 Conclusion 34 6.1 General 6.2 Revitalization Context 7 Sources 35 8 Appendix 36 Appendix 1 - Union Station Designation By-law (City of Toronto By-law 948-2005) Appendix 2 - Heritage Easement Agreement between The Toronto Terminals Railway Company Limited and the City of Toronto dated June 30, 2000 Appendix 3 - Heritage Character Statement, 1989 Appendix 4 - Commemorative Integrity Statement, 2000 Reissued: 18 September 2017 i ExEcutivE Summary This Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) revises the HIA dated January 16, 2017 in order to evaluate the impact of proposed work on existing resources at the subject site, based on an established understanding of their heritage value and attributes derived from the Heritage Statement Report - Union Station Complex, completed by Taylor Hazell Architects in June 2016 and the Union Station Trainshed Heritage Impact Assessment by Taylor Hazell Architects from July 2005. -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. , ,'',r.·- .. ' Ulli S. Watkiss 7 1 ________I :· _: ;.'~~··.'..'_ ~: ~--~ :: ·:~ :. :.-~· __ • •1...-------------~Cit Clerk City Clerk's Office Secretariat Tel: 416·392·7033 Christine Archibald Fax: 416-392-1879 Oct: 2 2 2004 Toronto and East York Community Council e-mail: [email protected] City Hall, 41h Floor, West "Web: www.toronto.ca 100 Queen Street West --------------- Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 - ?00" • aoA 71 FRONT STREET WEST CITY OF TORONTO, PROVINCE OF ONTARlO • NOTICE OF INTENTION TO DESIGNATE City of Toronto Ontario Heritage Foundation Corporate Services 10 Adelaide Street East Joan Anderton, Commissioner Toronto, Ontario 4th Floor, East Tower MSC 1J3 100 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Take notice that Toronto City Council intends to designate the lands and buildings known municipally as 71 Front Street West (Union Station) (Toronto Centre-Rosedale, Ward 28) under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act . • Reasons for Designation The property ,at 71 Front Street West is recommended for designation under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act for its cultural resource value or interest. Union Station was completed in 1927 as the shared terminal of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Grand Trunk Railway (later part of Canadian National Railways). -

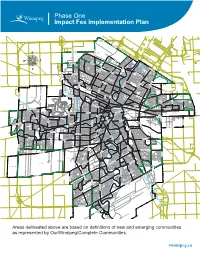

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

The Canadian Rail the Chateau Style Hotels

THE CANADIAN RAIL A. THE CHATEAU STYLE HOTELS 32 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 18:2 WAY HOTEL REVISITED: OF ROSS & MACFARLANE 18.2 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 33 Figure 6 (previous page). Promotional drawing of the Chateau Laurier Hotel, Ottawa, showing (left to right) the Parliament Buildings, Post Office, Chateau Laurier Hotel, and Central Union Passenger Station. Artist unknown, ca. 1912. (Ottawa City Archives, CA7633) Figure 1 (right). Chateau Frontenac Hotel, Quebec City, 1892-93; Bruce Price, architect. (CP Corporate Archives, A-4989) TX ~h the construction of the Chateau Frontenac Hotel in 1892-93 on the heights of r r Quebec City (figure 1), American architect Bruce Price (1845-1903) introduced the chateau style to Canada. Built for the Canadian Pacific Railway, the monumental hotel estab lished a precedent for a series of distinctive railway hotels across the country that served to as sociate the style with nationalist sentiment well into the 20th century.1 The prolonged life of the chateau style was not sustained by the CPR, however; the company completed its last chateauesque hotel in 1908, just as the mode was being embraced by the CPR's chief com petitor, the Grand Trunk Railway. How the chateau style came to be adopted by the GTR, and how it was utilized in three major hotels- the Chateau Laurier Hotel in Ottawa, the Fort Garry Hotel in Winnipeg, and the Macdonald Hotel in Edmonton -was closely related to the background and rise to prominence of the architects, Montreal natives George Allan Ross (1879-1946) and David Huron MacFarlane (1875-1950). According to Lovell's Montreal City Directory, 1900-01, George Ross2 worked as a draughtsman in the Montreal offices of the GTR, which was probably his first training in ar chitecture, and possibly a consideration when his firm later obtained the contracts for the GTR hotels. -

Summary of Results: 2018 Manitoba 55 Plus Games

Summary of Results: 2018 Manitoba 55 Plus Games Event Name or Team Region 1 km Predicted Nordic Walk Gold Steen Raymond Interlake Silver Mitchell Lorelie Westman Bronze Klassen Sandra Eastman 3 km Predicted Walk/Run Gold Spiring Britta Assiniboine Park/Fort Garry Silver Reavie Cheryl Parkland Bronze Heidrick Wendy Fort Garry/Assiniboia 16km Predicted Cycle Gold Jones Norma City Centre Silver Hansen Bob City Centre Bronze Moore Bob Westman 5 Pin Bowling Singles Women 55+ Gold MARION SINGLE Central Plains Silver SHARON PROST Westman Bronze SHIRLEY CHUBEY Eastman Women 65+ Gold OLESIA KALINOWICH Parkland Silver BEV VANDAMME Parkland Bronze RHONDA VAUDRY Westman Women 75+ Gold JEAN YASINSKI EK/Transcona Silver VICKY BEYKO Parkland Bronze DONNA GARLAND Westman Women 85+ Gold GRACE JONES Westman Silver EVA HARRIS EK/Transcona Men 55+ Gold DES MURRAY Westman Silver JERRY SKRABEK Ek/Transcona Bronze BERNIE KIELICH Eastman Men 65+ Gold HARVEY VAN DAMME Parkland Silver FRANK AARTS Westman Bronze JAKE ENNS Westman Men 75+ Gold FRANK REIMER Eastman Silver MARRIS BOS Central Plains Bronze NESTOR KALINOWICH Parkland Men 85+ Gold HARRY DOERKSEN EK/Transcona Silver LEO LANSARD EK/Transcona Bronze MELVIN OSWALD Westman 5 Pin Bowling Team 55+ Mixed Gold Carberry 1 Westman Silver OK Gals Westman Bronze Plumas Pin Pals Central Plains 65+ Mixed Gold Carberry 2 Westman Silver Parkland Parkland Bronze Hot Shots Westman 75+ Mixed Gold EK/Transcona EK/Transcona Silver Blumenort Eastman Bronze Strike Force Parkland 8 Ball 55+ Gold Dieter Bonas Assiniboine Park/Fort Garry Silver Rheal Simon Pembina Valley Bronze Guy Jolicoeur Eastman 70+ Gold Alfred Zastre Parkland Silver Denis Gaudet St.