178 CHAPTER FOUR “Effect! Effect!”: Immediacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène DU 15 AU 28 OCTOBRE 2013 6 REPRESENTATIONS Théâtre des Champs-Elysées SERVICE DE PRESSE +33 1 49 52 50 70 theatrechampselysees.fr La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la RESERVATIONS programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. +33 1 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr Spontini 5 La Vestale La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène Emmanuel Clolus décors Marguerite Bordat costumes Philippe Berthomé lumières Daria Lippi dramaturgie Ermonela Jaho Julia Andrew Richards Licinius Béatrice Uria-Monzon La Grande Vestale Jean-François Borras Cinna Konstantin Gorny Le Souverain Pontife Le Cercle de l’Harmonie Chœur Aedes 160 ans après sa dernière représentation à Paris, le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées présente une nouvelle production de La Vestale de Gaspare Spontini. Spectacle en français Durée de l’ouvrage 2h10 environ Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Théâtre de la Monnaie, Bruxelles MARDI 15, VENDREDI 18, MERCREDI 23, VENDREDI 25, LUNDI 28 OCTOBRE 2013 19 HEURES 30 DIMANCHE 20 OCTOBRE 2013 17 HEURES SERVICE DE PRESSE Aude Haller-Bismuth +33 1 49 52 50 70 / +33 6 48 37 00 93 [email protected] www.theatrechampselysees.fr/presse Spontini 6 Dossier de presse - La Vestale 7 La Vestale La nouvelle production du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées La Vestale n’a pas été représentée à Paris en version scénique depuis 1854. On doit donner encore La Vestale... que je l’entende une seconde fois !... Quelle Le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées a choisi, pour cette nouvelle production, de œuvre ! comme l’amour y est peint !.. -

EJC Cover Page

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS OF THE OPERA (1669-1919) By J.-G. PROD'HOMME " A NNO 1669."-This hybrid inscription, which may be read above the curtain of the Academie nationale de musique, re- minds the spectators that our foremost lyric stage is a crea- tion of Louis XIV, like its elder sisters the academies of painting and sculpture, of dancing, of inscriptions and belles-lettres, of sciences, and the Academy of Architecture, its junior. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

Mechanical Music Journal of the Musical Box Society International Devoted to All Automatic Musical Instruments

MECHANICAL MUSIC Journal of the Musical Box Society International Devoted to All Automatic Musical Instruments Volume 60, No. 3 May/June, 2014 65th Annual Meeting October 7 - 12, 2014 at the Bonaventure Resort & Spa in Weston, Florida "Our Backyard Museum" - The Jancko Collection Step back in time as you tour "Our Backyard Museum", the collection of Joel and Pam Jancko. Joel and Pam Jancko started their collection in the early 1990’s with only one building to house a couple of vehicles. This collection has grown through the years with additional buildings to encompass displays of an old town, a war room, a saloon, a soda fountain, a game room, a log cabin, a service station, a bicycle display, a fire station, a cinema, a street scene, a farm scene, a street clock, a steam engine, and even a fort. The Museum complex contains artifacts from the Civil War to WW1 and features many innovations from this time. Of most interest to our MBSI group will be the Music Room with a wide variety of instruments, including an Imhof & Mukle, a Seeburg H, a Wurlitzer CX, a Double Mills Violano, a Cremona K, a Weber Unika, an Encore Banjo, a Model B Harp, a Bruder band organ, a Limonaire band organ, a Bruder monkey organ, an American Photo Player and a classic Mortier, as well as a variety of cylinder and disc music boxes, organettes and phonographs. Making its debut at this meeting will be their newly acquired and installed 3 manual/11 rank Wurlitzer Opus 1616 theatre organ (model 235SP), expanded to 22 ranks. -

Library of Congress Medium of Performance Terms for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue anzhad USE clarinet BT double reed instrument USE imzad a-jaeng alghōzā Appalachian dulcimer USE ajaeng USE algōjā UF American dulcimer accordeon alg̲hozah Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE accordion USE algōjā dulcimer, American accordion algōjā dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, dulcimer, Kentucky garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. dulcimer, lap piano accordion UF alghōzā dulcimer, mountain BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah dulcimer, plucked NT button-key accordion algōzā Kentucky dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn mountain dulcimer accordion band do nally lap dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi plucked dulcimer with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī BT plucked string instrument UF accordion orchestra ngoze zither BT instrumental ensemble pāvā Appalachian mountain dulcimer accordion orchestra pāwā USE Appalachian dulcimer USE accordion band satāra arame, viola da acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute USE viola d'arame UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā arará folk bass guitar USE algōjā A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT guitar alpenhorn BT drum acoustic guitar USE alphorn arched-top guitar USE guitar alphorn USE guitar acoustic guitar, electric UF alpenhorn archicembalo USE electric guitar alpine horn USE arcicembalo actor BT natural horn archiluth An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE archlute required for the performance of a musical USE alphorn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic archiphone form. alto (singer) A microtonal electronic organ first built in 1970 in the Netherlands. BT performer USE alto voice adufo alto clarinet BT electronic organ An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE tambourine archlute associated with Western art music and is normally An extended-neck lute with two peg boxes that aenas pitched in E♭. -

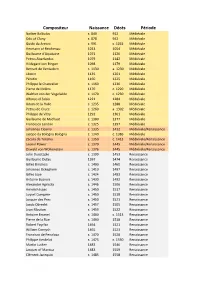

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

MARGUERITE VOLAVY BOHEMIAN PIANIST Scores Emphatic Success in Her Aeolian Hall Recital, January 29, 1921

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2004 VOLUME 41, NUMBER 5 MARGUERITE VOLAVY BOHEMIAN PIANIST Scores Emphatic Success in Her Aeolian Hall Recital, January 29, 1921 WHAT THE CRITICS SAID: . She has a m usical touch ., . nimble fingerS" . much of h er w ork s ho we d delicacy of feeling. The a u d ie nce rece iv ed her enthusiastic a lly." New York Tribune, Jan. 30, 1921. Plays wi t h energy . .. g lowing vitality that p iques y ou r in ter es t ." . New York Evening Mail,' Jan. 31, 1921. " It wa s in a n a tt ractive pr o gr am th at Marguer ite V olavy elected to demonstrate her pi an istic s ki ll a t Aeolia n H all on Saturda y eveni ng, J an. 29 . That her re cital a r o u sed co n sid erab le in tere st was made m anife st b y the good a ttenda nce. T he a ud ie nce was empha tic in its repeated tributes to th e pl a y e r. "Mis s Vo lavy em p loys in h er work a co nside rab l e dynamic scale, She is liberal wi t h tone a nd looks fr equently for m assive effec ts. Her interpreta ti ons are intelligent a nd in te resting. "The Ba ch-Busoni Ch a conne opened t he re cita l. There was no hesitancy in the mode of a ttack . -

German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's the Hall of Stars

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-04-17 German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's The Hall of Stars Allison Slingting Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Slingting, Allison, "German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's The Hall of Stars" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 3170. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s The Hall of Stars Allison Sligting Mays A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Heather Belnap Jensen, Chair Robert B. McFarland Martha Moffitt Peacock Department of Visual Arts Brigham Young University August 2012 Copyright © 2012 Allison Sligting Mays All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s The Hall of Stars Allison Sligting Mays Department of Visual Arts, BYU Master of Arts In this thesis I consider Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s The Hall of Stars in the Palace of the Queen of the Night (1813), a set design of Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), in relation to female audiences during a time of Germanic nationalism. -

Liszt and Christus: Reactionary Romanticism

LISZT AND CHRISTUS: REACTIONARY ROMANTICISM A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Robert Pegg May 2020 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Maurice Wright, Advisory Chair, Music Studies Dr. Michael Klein, Music Studies Dr. Paul Rardin, Choral Activities Dr. Christine Anderson, Voice and Opera, external member © Copyright 2020 by Robert Pegg All Rights Reserved € ii ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to examine the historical context of Franz Lizt’s oratorio Christus and explore its obscurity. Chapter 1 makes note of the much greater familiarity of other choral works of the Romantic period, and observes critics’ and scholars’ recognition (or lack thereof) of Liszt’s religiosity. Chapter 2 discusses Liszt’s father Adam, his religious and musical experiences, and his influence on the young Franz. Chapter 3 explores Liszt’s early adulthood in Paris, particularly with respect to his intellectual growth. Special attention is given to François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand and the Abbé Félicité de Lamennais, and the latter’s papal condemnation. After Chapter 4 briefly chronicles Liszt’s artistic achievements in Weimar and its ramifications for the rest of his work, Chapter 5 examines theological trends in the nineteenth century, as exemplified by David Friedrich Strauss, and the Catholic Church’s rejection of such novelties. The writings of Charles Rosen aid in decribing the possible musical ramifications of modern theology. Chapter 6 takes stock of the movements for renewal in Catholic music, especially the work of Prosper Gueranger and his fellow Benedictine monks of Solesmes, France, and of the Society of Saint Cecilia in Germany. -

Spontini's Olimpie: Between Tragédie Lyrique and Grand Opéra

Spontini’s Olimpie : between tragédie lyrique and grand opéra Olivier Bara Any study of operatic adaptations of literary works has the merit of draw - ing attention to forgotten titles from the history of opera, illuminated only by the illustrious name of the writer who provided their source. The danger, however, may be twofold. It is easy to lavish excessive attention on some minor work given exaggerated importance by a literary origin of which it is scarcely worthy. Similarly, much credit may be accorded to such-and-such a writer who is supposed – however unwittingly and anachronistically – to have nurtured the Romantic melodramma or the historical grand opéra , simply because those operatic genres have drawn on his or her work. The risk is of creating a double aesthetic confusion, with the source work obscured by the adapted work, which in turn obscures its model. In the case of Olimpie , the tragédie lyrique of Gaspare Spontini, the first danger is averted easily enough: the composer of La Vestale deserves our interest in all his operatic output, even in a work that never enjoyed the expected success in France. There remains the second peril. Olimpie the tragédie lyrique , premiered in its multiple versions between 1819 and 1826, is based on a tragedy by Voltaire dating from 1762. Composed in a period of transition by a figure who had triumphed during the Empire period, it is inspired by a Voltaire play less well known (and less admired) than Zaïre , Sémiramis or Le Fanatisme . Hence Spontini’s work, on which its Voltairean origin sheds but little light, initially seems enigmatic in 59 gaspare spontini: olimpie aesthetic terms: while still faithful to the subjects and forms of the tragédie lyrique , it has the reputation of having blazed the trail for Romantic grand opéra , so that Voltaire might be seen, through a retrospective illusion, as a distant instigator of that genre. -

LA VESTALE GASPARE SPONTINI Alessandro De Marchi & Eric Lacascade

PRESS FILE OPERA LA VESTALE GASPARE SPONTINI Alessandro de Marchi & Eric Lacascade 13, 15, 17, 20, 22 October 2015 20:00 25 October 2015 15:00 CIRQUE ROYAL / KONINKLIJK CIRCUS Opéra en trois actes, version française Livret de Victor-Joseph Etienne de Jouy Premiere Salle Montsansier, Paris, 15/12/1807 NEW PRODUCTION I – INTRODUCTION WITH BIOGRAPHIES THE FLAMES OF THE VESTAL ALTAR SET THE SCORE ALIGHT Since La Vestale, not a note of music has been written that wasn’t stolen from my scores!’ Gaspare Spontini was himself aware of how innovative and influential his score was. He turned opera in a new direction by conceiving the whole score on the basis of a compelling dramatic conception involving naturalistic effects, orchestration, and musical form, thereby pointing the way for such opera composers as Rossini, Wagner, Berlioz, and Meyerbeer. As a grand opera it was ahead of its time and was full of spectacular scenes showing a Vestal Virgin’s forbidden love for a Roman general; it made Spontini the most important composer of the Napoleonic period. Here directing his first opera, the French stage director Éric Lacascade focuses on a highly topical subject: ‘More than passionate love, what is at stake in this opera is the liberation of a woman who frees herself from the power of religious authority.’ COMPOSER & WORK Born in 1774 in Italy, Gaspare Spontini (1774-1851) imposed a new style to French music, mixing his Neapolitan inspiration to the genre of French lyric tragedy and thus creating what may be termed as Grand Historic Opera. The Italian composer, who became French in 1817, began a brilliant career in Rome and Venice after his studies at the Royal Conservatory of Naples.