Charge to Synod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diocesan Prayer Diary October 2020

Diocesan Prayer Diary October 2020 Day 1 Diocesan Bishop Peter Stuart and Nicki Diocesan Coralie Nichols (Diocesan Chief Executive) Ministries Linda Wilson (Corporation Secretary & Registrar) Wider Church The Diocese of Guadalcanal (Bp Nathan Tome & Selena) The Archbishop of Canterbury (Justin Welby) National Church Diocese of Adelaide (Abp Geoff Smith, Bps Denise Ferguson, Tim Harris and Chris McLeod) Parishes, schools The Cathedral and agencies of Katherine Bowyer and David (The Dean) the Diocese Angela Peverell (Sub Dean) David Cole and Sue (Canon Liturgist) Adamstown Chris Bird and Meri All Saints ANeW Arthur Copeman and Anabelle Rebecca Bishop, Kate Rogers and Amy Soutter - Ministry Assistants Wider Community Prime Minister and Cabinet The First Peoples of the Diocese especially the Awabakal, Biripi, Darkinjung, Geawegal, Kamilaroi, Worimi and Wonnarua peoples Page 1 Day 2 Diocesan Bishop PeterPeter Stuart Stuart and and Nicki Nicki Diocesan Sonia Roulston (Assistant Bishop – Inland Episcopate) Ministries Charlie Murry and Melissa (Assistant Bishop – Coastal Episcopate) Alison Dalmazzone and Jemma Hore (Executive Assistants) Wider Church The Diocese of Guadalcanal (Bp Nathan Tome & Selena) Catholic Diocese of Broken Bay (Bp Peter Comensoli, the Clergy and people) National Church Diocese of Armidale (Bp Rick Lewers) Parishes, schools Bishop Tyrrell Anglican College (NASC) and agencies of Sue Bain (Principal) the Diocese Georgetown Bryce Amner and Sally Cloke Barbara Bagley Hamilton Angela Peverell Hospital Chaplaincies Roger Zohrab -

Media Statement 16 March 2017 Statement from Bishop Peter Stuart

Media Statement 16 March 2017 Statement from Bishop Peter Stuart On behalf of the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle I express our considerable sadness at the news that Greg Thompson won't be returning to ministry as the Anglican Bishop of Newcastle. In his short time as our Bishop he has been the catalyst for deep cultural change around the protection of children and the support of victims of abuse. He called us to face our past and in doing so shape a healthy future. This will be his enduring legacy. As part of shaping a healthy future, we worked together in November to initiate independent external reviews of diocesan governance and the professional standards and redress processes. These reviews are well underway and will continue the crucial work of transforming the Diocese. Bishop Greg has led the Diocese to greater health. In 2013, the Diocesan family rejoiced that a ‘son of the diocese’ had been elected as the Diocesan Bishop. The clergy and people have delighted in his ministry in parishes, at the diocesan convention and synod. We have felt deep anguish for him and his family as we learnt of the abuse he experienced and the rejection by some in the Diocese. Throughout his ministry he has been committed to hearing the voices at the grassroots and empowering the vulnerable and people in need. Drawing on the great treasures in the teachings of Jesus, he has been unafraid of speaking strongly to the powerful to ensure transparency and promote justice. We are deeply thankful for Bishop Greg Thompson’s ministry as Anglican Bishop of Newcastle. -

Supplementary Business Paper 25-26

Supplementary Business Paper Third Session of the Fifty-Second Synod 25-26 October 2019 Synod assembles 11am Friday 25 October 2019 9.30am Saturday 26 October 2019 Christ Church Cathedral Diocese of Newcastle THIRD SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SECOND SYNOD Revised Business Paper FRIDAY 25 OCTOBER 2019 SATURDAY 26 OCTOBER 2019 SYNOD ASSEMBLES AT 11.00AM SYNOD ASSEMBLES AT 9.30AM 1. Opening Worship 2. Roll of Bishop, Clergy and Lay Representatives Bishop, Clergy and Lay Representatives to notify attendance 3. President to Declare Synod Constituted 4. Items Laid Upon the Table 4.1. Reports • Diocesan Council (including Professional Standards Activity Report) • Newcastle Anglican Church Corporation • General Fund and Budget Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Anglican Savings & Development Fund Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Trustees of Church Property Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Diocesan Ministry Council (including Formation and Mission Giving) • Newcastle Anglican Schools Corporation • Newcastle Anglican Schools Corporation Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Bishop Tyrrell Anglican College • Bishop Tyrrell Anglican College Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Lakes Grammar - An Anglican School • Lakes Grammar - An Anglican School Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Manning Valley Anglican College • Manning Valley Anglican College Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Scone Grammar School • Scone Grammar School Accounts as at 31 December 2018 • Anglican Care • Anglican Care Accounts as at 30 June 2018 • Samaritans Foundation • Samaritans Foundation -

Diocesan Prayer Diary

Our Bishop (Bishop Greg Thompson) has chosen to DIOCESAN include the figure of an Eaglehawk within his crest with the kind permission from the Indigenous people of the Hunter Region. The Eaglehawk is a totem for their communities. Its use marks the recognition of the First PRAYER DIARY Peoples in our Diocese and of the invitation to renew our lives Isaiah 40:31. The Wattle is used to reflect the August 2014 beauty of the environment and our commitment to care for the country God has blessed us with. Reception Day 1 Our Bishop and Greg Thompson and Kerry Assistant Bishop Peter Stuart and Nicki Diocesan John Cleary (Diocesan Business Manager) Ministries Jessica Murnane (ASDF) Wider Church The Diocese of Guadalcanal (Bp Nathan Tome & Selena) The Archbishop of Canterbury (Justin Welby) National Church Diocese of Adelaide (Abp Jeffrey Driver and Bp Tim Harris) Parishes, schools The Cathedral – Stephen Williams and Sue (The Dean) and agencies of Mark Watson (Canon Pastor) the Diocese David Cole and Sue (Canon Liturgist) Adamstown Chris Bird and Meri Anglican Men’s Network ANEW Arthur Copeman and Anabelle Ministry Assistants Bateau Bay Stephen Bloor and Adele, Kathy Dunstan and Stephen The Ministry Team Area Deanery of Newcastle Wider Community Prime Minister and Cabinet The First Peoples of the Diocese especially the Awabakal, Biripi, Darkinjung, Geawegal, Kamilaroi, Worimi and Wonnarua peoples. 1 Day 2 Our Bishop and Greg Thompson and Kerry Assistant Bishop Peter Stuart and Nicki Diocesan Stephen Pullin and Robyn (Archdeacon of Newcastle and -

Shaping a Healthy Future Professional Standards

Level 3, 134 King Street (PO Box 817) Newcastle NSW 2300 Phone: (02) 4926 3733 Web: newcastleanglican.org.au SHAPING A HEALTHY FUTURE For five years Anglican Church Newcastle has been engaged committed to meeting the ongoing counselling expenses of with the work of the Royal Commission into Institutional survivors. It is waiting on the Government and the Anglican Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. We have faced our past Church nationally so that it can join the National Redress failures and the profound impact on people across this region. Scheme. Each year around 300 people from the parishes, schools and The Diocese looks forward to the NSW Government making agencies gather at a meeting with the Anglican Bishop in an the changes that would allow Anglican Church Newcastle to event called Synod to deliberate on Anglican Church life. The be a designated agency for the purposes of child protection Bishop and Synod have expressed their sincere apology to under the NSW Ombudsman Act survivors of abuse. They have committed the Anglican Church Building on the legacy of Bishop Greg Thompson, Anglican Newcastle to do all that is necessary to provide redress and Church Newcastle is shaping a healthy future in which support to survivors. people can flourish by the grace of God and the grace of the Since we began paying redress, 38 people have applied, or communities the Church is called to serve. are highly likely to apply, for redress. These applications relate Bishop Peter Stuart became the Anglican Bishop on to 19 perpetrators. Our current estimated total for redress 2 February 2018. -

Diocesan Prayer Diary

Our Bishop (Bishop Greg Thompson) has chosen to include the figure of an Eaglehawk within his crest DIOCESAN with the kind permission from the Indigenous people of the Hunter Region. The Eaglehawk is a totem for their communities. Its use marks the recognition of the First Peoples in our Diocese and of the invitation PRAYER DIARY to renew our lives Isaiah 40:31. The Wattle is used to reflect the beauty of the environment and our February 2014 commitment to care for the country God has blessed us with. Day 1 Our Bishop and Greg Thompson and Kerry Assistant Bishop Peter Stuart and Nicki Diocesan John Cleary (Diocesan Business Manager) Ministries Jessica Read (ASDF) Wider Church The Diocese of Guadalcanal (Bp Nathan Tome & Selena) The Archbishop of Canterbury (Justin Welby) National Church Diocese of Adelaide (Abp Jeffrey Driver and Bp Tim Harris) Parishes, schools The Cathedral – Stephen Williams and Sue (The Dean) and agencies of Mark Watson (Canon Pastor) the Diocese David Cole and Sue (Canon Liturgist) Adamstown Chris Bird and Meri Anglican Men’s Network ANEW Arthur Copeman and Anabelle Ministry Assistants Bateau Bay Stephen Bloor and Adele, Kathy Dunstan and Stephen The Ministry Team Area Deanery of Newcastle Wider Community Prime Minister and Cabinet The First Peoples of the Diocese especially the Awabakal, Biripi, Darkinjung, Geawegal, Kamilaroi, Worimi and Wonnarua peoples. 1 Day 2 Our Bishop and Greg Thompson and Kerry Assistant Bishop Peter Stuart and Nicki Diocesan Stephen Pullin and Robyn (Archdeacon of Newcastle and Ministries -

Statement from the Bishop of Newcastle

STATEMENT BY THE ANGLICAN BISHOP OF NEWCASTLE THE RIGHT REVEREND DR PETER STUART BISHOP RICHARD APPLEBY 3 December 2019 Summary • Bishop Peter Stuart accepted finding that Bishop Appleby not fit to be employed by any church body without conditions • Bishop Appleby cannot engage in any ministry as a bishop nor present himself as a bishop in the Diocese of Newcastle for 3 years • Bishop Appleby must satisfy the Director of Professional Standards about his knowledge of and commitment to reporting disclosures of child sexual abuse before being able to exercise ministry as a bishop. • This decision is being communicated to all Diocesan Bishops in Australia and all clergy in the Diocese of Newcastle Detailed Statement Bishop Richard Appleby was the Auxiliary Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle from 1983 until 1992 serving Bishop Alfred Holland. Bishop Appleby went on to serve as the Bishop of the Northern Territory from 1992 until 1999 when he became an Assistant Bishop in the Diocese of Brisbane until 2006. He administered the Diocese of Brisbane in 2001. During the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse a witness known as CKA spoke of the serious sexual abuse perpetrated against him, when he was aged between 10 and 14 years, old by the Reverend George Parker (deceased) in the years 1971 - 1975. CKA’s account is harrowing both because of the abuse itself and the subsequent response of officials of the Diocese to CKA and his family. CKA gave evidence to the Royal Commission that he disclosed the sexual abuse by George Parker to Bishop Appleby in 1984. -

Diocesan Prayer Diary

Our Bishop (Bishop Greg Thompson) has chosen to include the figure of an Eaglehawk DIOCESAN within his crest with the kind permission from the Indigenous people of the Hunter Region. The Eaglehawk is a totem for their communities. Its use marks the recognition of PRAYER DIARY the First Peoples in our Diocese and of the invitation to renew our lives Isaiah 40:31. The March 2016 Wattle is used to reflect the beauty of the environment and our commitment to care for the country God has blessed us with. Day 1 Our Bishop and Greg Thompson and Kerry Assistant Bishop Peter Stuart and Nicki Diocesan Ministries John Cleary & Vanessa (Diocesan Business Manager) Linda Wilson and Laurence (Parish and Administrative Services Manager) Wider Church The Diocese of Guadalcanal (Bp Nathan Tome & Selena) The Archbishop of Canterbury (Justin Welby) National Church Diocese of Adelaide (Abp Jeffrey Driver, Bps Tim Harris and Chris McLeod) Parishes, schools The Cathedral and agencies of the Stephen Williams and Sue (The Dean) Diocese Paul West and Sally (Canon Residentiary) – from May 15 David Cole and Sue (Canon Liturgist) Adamstown Chris Bird and Meri ANEW Arthur Copeman and Anabelle Samuel Chiswell, Adam Matthews, Amy Soutter and Cathy Young - Ministry Assistants Birmingham Gardens Lyle Hughes and Lorraine (Locum) Area Deanery of Newcastle Regional Archdeacon – Arthur Copeman and Anabelle Wider Community Prime Minister and Cabinet The First Peoples of the Diocese especially the Awabakal, Biripi, Darkinjung, Geawegal, Kamilaroi, Worimi and Wonnarua peoples -

Standing Committee Reports

THE ANGLICAN CHURCH OF AUSTRALIA FIFTEENTH GENERAL SYNOD 2010 Melbourne 18-23 September 2010 GENERAL SYNOD PAPERS BOOK 3 STANDING COMMITTEE REPORTS ©The Anglican Church of Australia Trust Corporation 2010 Published by: The Standing Committee of the General Synod of The Anglican Church of Australia General Synod Office Level 9, 51 Druitt Street, Sydney, 2000, New South Wales, Australia STANDING COMMITTEE REPORTS CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3-001 2 MEMBERSHIP OF STANDING COMMITTEE AS AT 18 APRIL 2010 3-002 3 SUMMARY OF BUSINESS 2008-2010 3-006 4 ACTION TAKEN ON RESOLUTIONS OF THE FOURTEENTH SESSION OF GENERAL SYNOD 3-013 4.1 Professional Standards 4.2 Social Issues 4.3 Mission 4.4 Liturgy and Worship 4.5 Ministry 4.6 Anglican Communion, Ecumenical and Inter-Faith 4.7 Finance 4.8 Appreciation 4.9 Administration of Synod 5 ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER MINISTRY 3-055 5.1 Report of Joint Working Group of NATSIAC and Standing Committee 5.2 Summary of Report of Committee to Review Indigenous Ministry 6 ANGLICAN COMMUNION COVENANT 3-069 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Should Australia enter into the Anglican Communion Covenant? 6.3 Covenant in an Anglican Context 6.4 The Political Implications of signing the Covenant 6.5 The Covenant proposed for the Anglican Communion is not a good idea 7 WOMEN BISHOPS – DEVELOPMENTS SINCE 2007 3-083 8 GENERAL SYNOD VOTING SYSTEM 3-093 9 REVIEW OF COMMISSIONS, TASK FORCES AND NETWORKS 3-103 10 ANGLICAN CHURCH OF AUSTRALIA TRUST CORPORATION 3-110 11 APPELLATE TRIBUNAL 3-111 12 GENERAL SYNOD LEGISLATION 3-112 12.1 Introduction -

July 2021 Prayer Diary

Anglican Diocese of Melbourne Prayer Diary July 2021 July 2021 Sun 4 The Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea; The Diocese of Armidale (Bp Rod Chiswell, Clergy & People); Social ResponsibiliEes CommiFee (Gordon Preece, Chair); St Andrew's Aberfeldie (Michael Danaher, Lynda Crossley); St Thomas' Burwood – Pastoral Services (Bp Paul Barker); St James’ Pakenham – ConfirmaEon (Bp Paul Barker); Mon 5 The Diocese of Ballarat (Bp Garry Weatherill, Clergy & People); St Silas and St Anselm Albert Park (Sophie Watkins); Tue 6 The Diocese of Bathurst (Bp Mark Calder, Clergy & People); Christ Church Grammar School (Neil Andary, Principal; Linda Fiske, Chaplain); Parish of St Eanswythe's, Altona w. St Clement's, Laverton (Chris Lancaster, KaEe Bellhouse); Wed 7 The Diocese of Bendigo (Bp MaF Brain, Clergy & People); Police Force Chaplains (Drew Mellor, David Thompson & other Chaplains) and members of the Police Force; All Saints' Ascot Vale (Andrew Esnouf); Thu 8 The Diocese of Brisbane (Abp Phillip Aspinall, Regional Bps Jeremy Greaves, Cameron Venables, John Roundhill, Clergy & People); Archdeaconry of Dandenong; St MaFhew's Ashburton (Kurian Peter); Fri 9 The Diocese of Bunbury (Bp Ian CouFs, Clergy & People); Firbank Grammar School (Jenny Williams, Principal; ChrisEne Cro], chaplain); Sat 10 The Diocese of Canberra & Goulburn (Bp Mark Short, Asst Bps Stephen Pickard, Carol Wagner, Clergy & People); SparkLit (Michael Collie, NaEonal Director); Parish of Holy Trinity, Bacchus Marsh w. Christ Church, Myrniong and St George's Balliang (Richard Litjens); -

SPRING EDITION Vol. 13

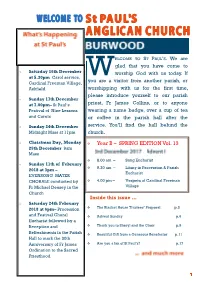

ELCOME TO ST PAUL’S. We are glad that you have come to Saturday 16th December worship God with us today. If at 5.30pm Carol service, W Cardinal Freeman Village, you are a visitor from another parish, or Ashfield worshipping with us for the first time, please introduce yourself to our parish Sunday 17th December at 7.00pm– St Paul‘s priest, Fr James Collins, or to anyone Festival of Nine Lessons wearing a name badge, over a cup of tea and Carols or coffee in the parish hall after the Sunday 24th December service. You’ll find the hall behind the Midnight Mass at 11pm church. Christmas Day, Monday Year B – SPRING EDITION Vol. 13 25th December 9am Mass 8.00 am – Sung Eucharist Sunday 11th of February 9.30 am – Litany in Procession & Parish 2018 at 3pm – Eucharist EVENSONG MATER CHORALE conducted by 4.00 pm – Vespers at Cardinal Freeman Fr Michael Deasey in the Village Church Inside this issue … Saturday 24th February 2018 at 6pm– Procession The Blacket House Trustees’ Proposal p.3 and Festival Choral Advent Sunday p.6 Eucharist followed by a Reception and Thank you to Sheryl and the Choir p.9 Refreshments in the Parish Beautiful Gift from a Generous Benefactor p.11 Hall to mark the 30th Anniversary of Fr James Are you a fan of St Paul’s? p.17 Ordination to the Sacred Priesthood People needing wheelchair access can enter St Paul’s most conveniently by the First aid kits are located on the wall of door at the base of the belltower. -

The Anglican Diocese of Newcastle Report of the Diocesan Council 1 July 2016 to 31 July 2017

The Anglican Diocese of Newcastle Report of the Diocesan Council 1 July 2016 to 31 July 2017 The Diocesan Council held 13 Meetings during the reporting period. The record of attendance is set out below. Attendance Name Eligible meetings to attend Meetings (1 July 2016 – 31 July 2017) attended Present The Right Reverend Gregory Thompson 10 2 The Right Reverend Dr Peter Stuart 13 13 The Honorable Mr Justice Peter Young AO, 13 7 (Chancellor) His Honour Mr Christopher Armitage, 13 1 (Deputy Chancellor) The Venerable Canon David Battrick 13 11 Ms Bev Birch 13 13 The Reverend Canon Katherine Bowyer 13 11 The Venerable Canon Arthur Copeman 13 12 The Venerable Wendy Dubojski 13 3 Mr Stephen Dunstan 13 11 Mr Peter Gardiner 13 11 The Reverend Canon Janet Killen 13 12 The Reverend Dr Fergus King 13 10 The Venerable Charlie Murry 13 10 The Reverend Canon Dr Julia Perry 13 11 The Venerable Canon Sonia Roulston 13 11 Mr Richard Turnbull 13 12 Mrs Lyn Wickham 13 11 The Very Reverend Stephen Williams 13 11 Mrs Sue Williams 13 13 The Reverend Murray Woolnough 13 12 In Attendance Mr John Cleary 6 0 Mr Stephen Phillips 1 1 Mrs Linda Wilson 13 11 Conflicts of Interest It is the standing practice of the Diocesan Council to be advised of any conflicts of interest at the commencement of each meeting. These conflicts are recorded in the minutes. The Royal Commission The Diocesan Council was informed to the extent possible about the proceedings in Case Study 42 and Case Study 52.