AN ASSESSMENT of WASTE MANAGEMENT OPERATION in MALAYSIA: CASE STUDY on KUALA LANGAT and SEPANG Innocent A. Jereme Phd Student, I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Society of Malaysia Bulletin 49

Annual Geological Conference 2004, June 4 – 6 Putra Palace, Kangar, Perlis, Malaysia Concentration of heavy metals beneath the Ampar Tenang municipal open-tipping site, Selangor, Malaysia ABDUL RAHIM SAMSUDIN, BAHAA-ELDIN ELWALI A. RAHIM, WAN ZUHAIRI WAN YAACOB & ABDUL GHANI RAFEK Geology Program, School of Environment & Natural Resources Sciences, Faculty of Science & Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor Abstract: Heavy metals namely Cu, Cr, Ni, Zn, Pb, and Co in soil horizons beneath the Ampar Tenang municipal open-tipping site have been extensively investigated through examination of twenty one representative triplicate soil samples that were collected from nine auger holes distributed in three locations within the study area. These include upstream (ATU), downstream (ATD), and soil- waste interface (ATI). Results obtained for ATI revealed considerably higher concentration levels of most of the elements analyzed compared to ATD and ATU. Moreover, Cr, Zn and Pb had shown higher levels of concentration amongst all examined metals. It was found that in most cases, the heavy metal concentration was generally high at the surface and downwards up to 60 cm depth, then decreased relatively with increasing depth. It was shown that, in addition to the vertical infiltration of leachate from the solid waste, the hydrological regime of groundwater has also a strong impact on the contaminants distribution in soils below the site. INTRODUCTION of 0.5 to 5.5 m thick Beruas Formation with peat layer at the top, the clayey Gula Formation and the Kempadang Landfilling which is still the most popular form of Formation (MGD, 2001; Bosch, 1988). Immediately, municipal solid waste treatment in many countries now, below the peat there is a layer of very soft to soft takes up lots of areas and leads to a serious pollution to its compressible marine clay (Omar et al., 1999). -

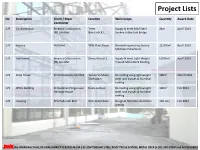

Project Lists

Project Lists No Description Client / Main Location Work Scope Quantity Award Date Contractor 175 Condominium Binastra Construction Treez Supply & erect Mild Steel 24m April’ 2013 (M) Sdn Bhd Bukit Jalil,K.L. Sunken Lobby Link Bridge 174 Factory YKGI Bhd YKGI Plant,Kapar. Dismantling existing factory 12,000m2 April’ 2013 Mild Steel Structures 173 Apartment Binastra Construction Danau Kota,K.L. Supply & erect Light Weight 6,000m2 April’ 2013 (M) Sdn Bhd Truss & Metal Deck Roofing 172 Shop House Penril Datability Sdn Bhd Taman Sri Muda, Re-roofing using light weight 280m2 March’2013 Shah Alam steel roof trusses & fix metal roofing 171 Office Building Perbadanan Pengurusan Kuala Lumpur. Re-roofing using light weight 300m2 Feb’2013 Heritage House steel roof trusses & fix metal roofing 170 Housing KPG Padu Sdn Bhd Nilai,N.Sembilan Design & fabricate steel drain 150 sets Feb’2013 grating DNK, We-MANUFACTURE,DESIGN,FABRICATE&INSTALL M.S & LIGHT WEIGHT STEEL ROOF TRUSS SYSTEM, METAL DECK & CEILLING STRIP and ACCESSORIES Project Lists No Description Client / Main Location Work Scope Quantity Award Date Contractor 169 Steel Support Frame for Archi-Foam Sdn Bhd Mont Kiara Kuala Design & build steel frame 3 mT Dec’2012 Condominium Lumpur support for light weight foam concrete 168 Ware House extension Kara Marketing (M) Sdn Puchong Selangor Design & build mild steel 30 mT Nov’2012 steel structure Bhd structure for warehouse extension 167 Shop Houses 24 Units Hong & Hong Groups Kota Kemuning, Design & build light weight steel 3,350 m2 Oct’2012 Sdn Bhd Shah Alam roof trusses & fax metal deck roofing 166 Workshop Muner Hanafiah Taman Tun Dr. -

Persada Brochure 231116.Pdf

230mm x 305mm (cover front) 230mm x 305mm (inside cover front) SETTING BENCHMARKS, ADDING VALUE Bandar Bukit Raja was launched in 2002 with a mixed residential development comprising of affordable, medium and higher end homes. As its planned evolution progresses, Bandar Bukit Raja has become a highly successful and sought-after model township that has now encompassed commercial, retail and Sime Darby Business Park as part of its integration ambition. Its vital position on the Greater Kuala Lumpur footprint ensures its continued importance in location, value and expandibility. Stage 3 (Future Development) A THRIVING COMMUNITY IN KLANG Stage 2 (Future Development) Sprawling over 4,405 acres, Bandar Bukit Raja is an integrated and P self-contained township in Klang. R O P Launched in 2002, it consists not O S only of residential properties but E D also commercial, institutional and W E industrial properties. S 125 acres T Town Park C O A The Bandar Bukit Raja community comes alive S within a well-planned layout and amenities that T E JALAN MERU offer accessible convenience and ease. A strategic Sales Gallery X P location and alluring living standards make it the R E preferred neighbourhood in Klang. S S W A Y NEW NORTH KLANG STRAITS BYPASS Shah Alam 62km 28km 7km 12km 28km 37km *Artist’s impression only COMMUNITY-LIVING FACILITIES Experience it all at Persada, the perfect setting for you and your family at Bandar Bukit Raja. Designed for your ideal living, Persada is the latest 2-storey link home development project by Sime Darby Property in Bandar Bukit Raja, an integrated and self-contained township in Klang. -

CBD Sixth National Report

SIXTH NATIONAL REPORT OF MALAYSIA to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) December 2019 i Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ vi List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................... vi Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................... vii Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 3 CHAPTER 1: UPDATED COUNTRY BIODIVERSITY PROFILE AND COUNTRY CONTEXT ................................... 1 1.1 Malaysia as a Megadiverse Country .................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Major pressures and factors to biodiversity loss ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Implementation of the National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025 ........................................ -

Lifetime Generation Homes

FREEHOLD Lifetime Generation Homes In Nature’s Embrace In close proximity to a 125-acre town park, Azira homes feature a complete array of facilities on top of safety and security with its single entry and exit point. A Beautiful Life Our sustainably designed homes are set in the beautiful scenery of open gardens, promoting a wholesome lifestyle and family bonding. Enjoy a life of smiles and precious moments as you relax in the company of your loved ones. Preserving Memories Azira’s open plan layout is inspired by modern living to suit your lifestyle needs, allowing you to appreciate the things that matter most in life—cherished quality time with your family. Presenting a unique approach to modern urban living with a focus on sustainability, Bandar Bukit Raja homes feature specially crafted design principles to offer an elevation of everyday living. Natural Ventilation Natural Lighting In Harmony With Nature Multi-Generational Homes SITE PLAN Phase 2 Masterplan TO JALAN MERU INDUSTRIAL LOTS INDUSTRIAL LOTS TO PEKAN MERU / PUNCAK ALAM INDUSTRIAL LOTS WEST COAST EXPRESSWAY UNDER CONSTRUCTION JALAN MERU EAST ENTRANCE TOWN PARK CASIRA TOWN PARK TOWN PARK PERSADA JALAN SUNGAI PULOH SOUTH ENTRANCE TO KAPAR Azira 2-Storey Terrace Homes 20’ x 75’ 111 units A1 / A2 - Intermediate Unit E1 / E2 / E3 - End Unit C1 / C2 - Corner Unit Green Area A1/A2 E1/E2 INTERMEDIATE LOT END LOT Built Up: Built Up: 1,901 sqft 2,130 sqft 6100 6100 6700 6700 YARD ROOF YARD ROOF ABOVE BATH 1 BATH 2 ABOVE YARD BATH 1 BATH 2 GUEST GUEST YARD BATH BATH KITCHEN KITCHEN -

HP Resellers in Selangor

HP Resellers in Selangor Store Name City Address SNS Network (M) SDN BHD(Jusco Balakong Aras Mezzaqnize, Lebuh Tun Hussien Onn Cheras Selatan) Courts Mammoth Banting No 179 & 181 Jalan Sultan Abdul Samad Sinaro Origgrace Sdn Bhd Banting No.58, Jalan Burung Pekan 2, Banting Courts Mammoth K.Selangor No 16 & 18 Jalan Melaka 3/1, Bandar Melawati Courts Mammoth Kajang No 1 Kajang Plaza Jalan Dato Seri, P. Alegendra G&B Information Station Sdn Bhd Kajang 178A Taman Sri Langat, Jalan Reko G&B Information Station Sdn Bhd Kajang Jalan Reko, 181 Taman Sri Langat HARDNET TECHNOLOGY SDN BHD Kajang 184 185 Ground Floor, Taman Seri Langat Off Jalan Reko, off Jalan Reko Bess Computer Sdn Bhd Klang No. 11, Jalan Miri, Jalan Raja Bot Contech Computer (M) Sdn Bhd Klang No.61, Jalan Cokmar 1, Taman Mutiara Bukit Raja, Off Jalan Meru Courts Mammoth Berhad Klang No 22 & 24, Jalan Goh Hock Huat Elitetrax Marketing Sdn Bhd (Harvey Klang Aeon Bukit Tinggi SC, F42 1st Floor Bandar Bukit Norman) Tinggi My Gameland Enterprise Klang Lot A17, Giant Hypermarket Klang, Bandar Bukit Tinggi Novacomp Compuware Technology Klang (Sa0015038-T) 3-00-1 Jln Batu Nilam 1, Bdr Bukit Tinggi. SenQ Klang Unit F.08-09 First Floor, Klang Parade No2112, Km2 Jalan Meru Tech World Computer Sdn Bhd Klang No. 36 Jalan Jasmin 6 Bandar Botanic Thunder Match Sdn Bhd Klang JUSCO BUKIT TINGGI, LOT S39, 2ND FLOOR,AEON BUKIT TINGGI SHOPPING CENTRE , NO. 1, PERSIARAN BATU NILAM 1/KS6, , BANDAR BUKIT TINGGI 2 41200 Z Com It Store Sdn Bhd Klang Lot F20, PSN Jaya Jusco Bukit Raja Klang, Bukit Raja 2, Bandar Baru Klang Courts Mammoth Nilai No 7180 Jalan BBN 1/1A, Bandar Baru Nilai All IT Hypermarket Sdn Bhd Petaling Jaya Lot 3-01, 3rd Floor, Digital Mall, No. -

B. Barendregt the Sound of Longing for Homeredefining a Sense of Community Through Minang Popular Music

B. Barendregt The sound of longing for homeRedefining a sense of community through Minang popular music In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 158 (2002), no: 3, Leiden, 411-450 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 02:24:12PM via free access BART BARENDREGT The Sound of 'Longing for Home' Redefining a Sense of Community through Minang Popular Music Why, yes why, sir, am I singing? Oh, because I am longing, Longing for those who went abroad, Oh rabab, yes rabab, please spread the message To the people far away, so they'll come home quickly (From the popular Minangkabau traditional song 'Rabab'.) 1. Introduction: Changing mediascapes and emerging regional metaphors Traditionally each village federation in Minangkabau had its own repertoire of musical genres, tunes, and melodies, in which local historiography and songs of origin blended and the meta-landscape of alam Minangkabau (the Minangkabau universe) was depicted.1 Today, with the ever-increasing disper- sion of Minangkabau migrants all over Southeast Asia, the conception of the Minangkabau world is no longer restricted to the province of West Sumatra. 1 Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 34th Conference of the International Council of Traditional Music, Nitra, Slovakia, August 1996, and the VA/AVMI (Leiden Uni- versity) symposium on Media Cultures in Indonesia, 2-7 April 2001. Its present form owes much to critical comments received from audiences there. I would like to sincerely thank also my colleagues Suryadi, for his suggestions regarding the translations from the Minangkabau, and Robert Wessing, for his critical scrutiny of my English. -

BERT 2 Ringkasan Eksekutif

Environmental Impact Assessment Proposed Expansion of Recycle Pulp & Packaging Paper Plant, Mahkota Industrial Park, Kuala Langat, Selangor RINGKASAN EKSEKUTIF 1 PENGENALAN PROJEK Laporan Penilaian Impak Alam Sekitar (EIA) Jadual Kedua ini telah disediakan bagi Proposed Expansion of Recycle Pulp & Packaging Paper Plant, on Lot PT 41098, PT 41097 & PT 473, Mahkota Industrial Park, Banting, Mukim Tanjung 12, Daerah Kuala Langat, Selangor Darul Ehsan oleh Best Eternity Recycle Technology Sdn. Bhd. (BERT). Cadangan Projek ini akan melibatkan peningkatan dalam kadar pengeluaran tahunan kertas pembungkusan dari pengeluaran semasa sebanyak 700,000 tan setahun kepada 1,400,000 tan setahun. Cadangan pembangunan ini akan turut melibatkan pemerolehan tanah bersebelahan (Lot PT 41098, 17.97 ekar) menjadikan luas keseluruhan 132.72 ekar bagi memenuhi keperluan pembangunan. Komponen utama dalam cadangan pembangunan ini terdiri daripada: i. Kilang pengeluaran kertas pembungkusan tambahan (Mesin Kertas 3 dan 4); ii. Penambahan kapasiti loji rawatan air (WTP) iii. Penambahan kapasiti loji rawatan air sisa (WWTP) iv. Pembinaan Loji Kogenerasi Biomas Tapak Projek ini terletak kira-kira 6 km di timur laut bandar Banting, 14 km sebelah barat Dengkil, 20 km barat laut Lapangan Terbang Antarabangsa Kuala Lumpur (KLIA) dan 35 km barat daya ibu kota Kuala Lumpur, seperti yang ditunjukkan dalam Rajah ES-1. 1.1 Penggerak Projek Penggerak Projek adalah Best Eternity Recycle Technology Sdn. Bhd. (BERT), yang merupakan syarikat pelaburan asing dan juga anak syarikat kepada Lee & Man Paper Manufacturing Limited, China. Best Eternity Recycle Technology Sdn. Bhd. (1279344-A) Alamat : 35 & 35A, Jalan Emas 2, Bandar Sungai Emas, 42700 Banting, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Tel / Faks : +603-3181 1631 / +603-3181 1633 Hubungi : En. -

Coconut Water Vinegar Ameliorates Recovery of Acetaminophen Induced

Mohamad et al. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2018) 18:195 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-018-2199-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Coconut water vinegar ameliorates recovery of acetaminophen induced liver damage in mice Nurul Elyani Mohamad1, Swee Keong Yeap2, Boon-Kee Beh3,4, Huynh Ky5, Kian Lam Lim6, Wan Yong Ho7, Shaiful Adzni Sharifuddin4, Kamariah Long4* and Noorjahan Banu Alitheen1,3* Abstract Background: Coconut water has been commonly consumed as a beverage for its multiple health benefits while vinegar has been used as common seasoning and a traditional Chinese medicine. The present study investigates the potential of coconut water vinegar in promoting recovery on acetaminophen induced liver damage. Methods: Mice were injected with 250 mg/kg body weight acetaminophen for 7 days and were treated with distilled water (untreated), Silybin (positive control) and coconut water vinegar (0.08 mL/kg and 2 mL/kg body weight). Level of oxidation stress and inflammation among treated and untreated mice were compared. Results: Untreated mice oral administrated with acetaminophen were observed with elevation of serum liver profiles, liver histological changes, high level of cytochrome P450 2E1, reduced level of liver antioxidant and increased level of inflammatory related markers indicating liver damage. On the other hand, acetaminophen challenged mice treated with 14 days of coconut water vinegar were recorded with reduction of serum liver profiles, improved liver histology, restored liver antioxidant, reduction of liver inflammation and decreased level of liver cytochrome P450 2E1 in dosage dependent level. Conclusion: Coconut water vinegar has helped to attenuate acetaminophen-induced liver damage by restoring antioxidant activity and suppression of inflammation. -

First of All, I of Living Next to My Cyberjaya Campus at After

ANNUAL 20 12REPORT First of all, I DREAM of living next to my Cyberjaya Campus at After graduation, I look forward to working & living in the booming Iskandar area When I get married, I will be living close to my parents at Of course, I would want to bring up my children in an eco-paradise Finally, I plan to spend my golden years in a tranquil & luxurious setting Iskandar Malaysia Iconic residential towers Elevating luxury with high-rise residential towers that are both TM Southbay Plaza, Batu Maung M-city, Jalan Ampang M-Suites , Jalan Ampang architecturally impressive and One Lagenda, Cheras Icon Residence, Mont’ Kiara www.southbay.com.my 03-2162 8282 www.m-suites.com.my thoughtfully equipped with www.onelagenda.com.my www.icon-residence.com.my www.m-city.com.my lifestyle amenities. N 3º 9’23.37” E 101º 4’19.28” Johor Austine Suites, Tebrau Mah Sing i-Parc, Tanjung Pelapas The Meridin@Medini 07-355 4888 07-527 3133 1800-88-6788 / 07-355 4888 Lagenda@Southbay, Batu Maung Bayan Lepas Kuala Lumpur www.austinesuites.com.my www.mahsing.com.my www.mahsing.com.my 04-628 8188 N 1º 32’54” E 103º 45’5” N 1º 33.838’ E 103º 35.869’ N 1º 32’54” E 103º 47’5” www.southbay.com.my N 5º 17’7” E 100º 17’18” Johor Bahru Selangor Ferringhi Residence, Batu Ferringhi 04-628 8188 www.ferringhi-residence.com.my Dynamic integrated developments N 5º 17’7” E 100º 17’18” Combining commercial, residential and retail components within a Batu Ferringhi Cyberjaya development to provide discerning investors and residents alike with all of the lifestyle offerings of a modern venue. -

23 Feb 2017 (Jil.61, No.4, TMA No.10)

M A L A Y S I A Warta Kerajaan S E R I P A D U K A B A G I N D A DITERBITKAN DENGAN KUASA HIS MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Jil. 61 TAMBAHAN No. 4 23hb Februari 2017 TMA No. 10 No. TMA 27. AKTA CAP DAGANGAN 1976 (Akta 175) PENGIKLANAN PERMOHONAN UNTUK MENDAFTARKAN CAP DAGANGAN Menurut seksyen 27 Akta Cap Dagangan 1976, permohonan-permohonan untuk mendaftarkan cap dagangan yang berikut telah disetuju terima dan adalah dengan ini diiklankan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan disetuju terima dengan tertakluk kepada apa-apa syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan, syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan tersebut hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) Akta diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2) Akta itu, perkataan-perkataan “Permohonan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) yang diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2)” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan itu. Jika keizinan bertulis kepada pendaftaran yang dicadangkan daripada tuanpunya berdaftar cap dagangan yang lain atau daripada pemohon yang lain telah diserahkan, perkataan-perkataan “Dengan Keizinan” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan, menurut peraturan 33(3). WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN 2248 [23hb Feb. 2017 23hb Feb. 2017] PB Notis bangkangan terhadap sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan suatu cap dagangan boleh diserahkan, melainkan jika dilanjutkan atas budi bicara Pendaftar, dalam tempoh dua bulan dari tarikh Warta ini, menggunakan Borang CD 7 berserta fi yang ditetapkan. TRADE MARKS ACT 1976 (Act 175) ADVERTISEMENT OF APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS Pursuant to section 27 of the Trade Marks Act 1976, the following applications for registration of trade marks have been accepted and are hereby advertised. -

07.Hansard.271112

DEWAN NEGERI SELANGOR YANG KEDUA BELAS PENGGAL KELIMA MESYUARAT KETIGA Shah Alam, 27 November 2012 (Selasa) Mesyuarat dimulakan pada jam 10.00 pagi YANG HADIR Y.B. Dato’ Teng Chang Khim, DPMS (Sungai Pinang) (Tuan Speaker) Y.A.B. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Abdul Khalid bin Ibrahim PSM., SPMS., DPMS., DSAP. (Ijok) (Dato’ Menteri Besar Selangor) Y.B. Puan Teresa Kok Suh Sim (Kinrara) Y.B. Tuan Iskandar Bin Abdul Samad (Chempaka) Y.B. Tuan Dr. Haji Yaakob bin Sapari (Kota Anggerik) Y.B. Puan Rodziah bt. Ismail (Batu Tiga) Y.B. Puan Dr. Halimah bt. Ali (Selat Klang) Y.B. Tuan Liu Tian Khiew (Pandamaran) Y.B. Puan Elizabeth Wong Keat Ping (Bukit Lanjan) Y.B. Tuan Ean Yong Hian Wah (Seri Kembangan) 1 Y.B. Tuan Dr. Ahmad Yunus bin Hairi (Sijangkang) Y.B. Puan Haniza bt. Mohamed Talha (Taman Medan) (Timbalan Speaker) Y.B. Tuan Mohamed Azmin bin Ali (Bukit Antarabangsa) Y.B. Tuan Ng Suee Lim (Sekinchan) Y.B. Tuan Dr. Shafie bin Abu Bakar (Bangi) Y.B. Tuan Lee Kim Sin (Kajang) Y.B. Tuan Mat Shuhaimi bin Shafiei (Sri Muda) Y.B. Tuan Lau Weng San (KampungTunku) Y.B. Tuan Haji Saari bin Sungib (Hulu Kelang) Y.B. Tuan Muthiah a/l Maria Pillay (Bukit Malawati) Y.B. Tuan Philip Tan Choon Swee (Telok Datok) Y.B. Tuan Khasim bin Abdul Aziz (Lembah Jaya) Y.B. Tuan Amirudin bin Shari (Batu Caves) Y.B. Tuan Manoharan a/l Malayalam (Kota Alam Shah) Y.B. Puan Lee Ying Ha (Teratai) Y.B. Puan Hannah Yeoh Tseow Suan (Subang Jaya) Y.B.