12/6 Reading Assignment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Empire and Revolution : a Life of Sidney Bunting, 1873-1936

BETWEEN EMPIRE AND REVOLUTION: A LIFE OF SIDNEY BUNTING, 1873–1936 Empires in Perspective Series Editors: Emmanuel K. Akyeampong Tony Ballantyne Duncan Bell Francisco Bethencourt Durba Ghosh Forthcoming Titles A Wider Patriotism: Alfred Milner and the British Empire J. Lee Th ompson Missionary Education and Empire in Late Colonial India, 1860–1920 Hayden J. A. Bellenoit Transoceanic Radical: William Duane, National Identity and Empire, 1760–1835 Nigel Little Ireland and Empire, 1692–1770 Charles Ivar McGrath Natural Science and the Origins of the British Empire Sarah Irving Empire of Political Th ought: Indigenous Australians and the Language of Colonial Government Bruce Buchan www.pickeringchatto.com/empires.htm BETWEEN EMPIRE AND REVOLUTION: A LIFE OF SIDNEY BUNTING, 1873–1936 BY Allison Drew london PICKERING & CHATTO 2007 Published by Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Limited 21 Bloomsbury Way, London WC1A 2TH 2252 Ridge Road, Brookfi eld, Vermont 05036-9704, USA www.pickeringchatto.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. © Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Limited 2007 © Allison Drew 2007 british library cataloguing in publication data Drew, Allison Between empire and revolution : a life of Sidney Bunting, 1873–1936. – (Empires in per- spective) 1. Bunting, Sidney Percival, 1873–1936 2. Social reformers – South Africa – Biography 3. Communists – South Africa – Biography 4. Lawyers – South Africa – Biography 5. South Africa – Politics and government – 1909–1948 6. South Africa – Politics and government – 1836–1909 7. South Africa – Social conditions I. -

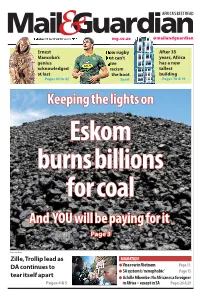

And YOU Will Be Paying for It Keeping the Lights On

AFRICA’S BEST READ October 11 to 17 2019 Vol 35 No 41 mg.co.za @mailandguardian Ernest How rugby After 35 Mancoba’s just can’t years, Africa genius give has a new acknowledged racism tallest at last the boot building Pages 40 to 42 Sport Pages 18 & 19 Keeping the lights on Eskom burns billions for coal And YOU will be paying for it Page 3 Photo: Paul Botes Zille, Trollip lead as MIGRATION DA continues to O Visa row in Vietnam Page 11 OSA system is ‘xenophobic’ Page 15 tear itself apart OAchille Mbembe: No African is a foreigner Pages 4 & 5 in Africa – except in SA Pages 28 & 29 2 Mail & Guardian October 11 to 17 2019 IN BRIEF ppmm Turkey attacks 409.95As of August this is the level of carbon Kurds after Trump Yvonne Chaka Chaka reneges on deal NUMBERS OF THE WEEK dioxide in the atmosphere. A safe number Days after the The number of years Yvonne Chaka is 350 while 450 is catastrophic United States Chaka has been married to her Data source: NASA withdrew troops husband Dr Mandlalele Mhinga. from the Syria The legendary singer celebrated the border, Turkey Coal is king – of started a ground and couple's wedding anniversary this aerial assault on Kurdish week, posting about it on Instagram corruption positions. Civilians were forced to fl ee the onslaught. President Donald Trump’s unex- Nigeria's30 draft budget plan At least one person dies every single day so pected decision to abandon the United States’s that we can have electricity in South Africa. -

The Johnny Clegg Band Opening Act Guitar, Vocals Jesse Clegg

SRO Artists SRO The Johnny Clegg Band Opening Act Guitar, Vocals Jesse Clegg The Johnny Clegg Band Guitar, Vocals, Concertina Johnny Clegg Guitar, Musical Director Andy Innes Keyboard, Sax, Vocals Brendan Ross Percussion Barry Van Zyl Bass, Vocals Trevor Donjeany Percussion Tlale Makhene PROGRAM There will be an intermission. Sunday, April 3 @ 7 PM Zellerbach Theatre Part of the African Roots, American Voices series. 15/16 Season 45 ABOUT THE ARTISTS Johnny Clegg is one of South Africa’s most celebrated sons. He is a singer, songwriter, dancer, anthropologist and musical activist whose infectious crossover music, a vibrant blend of Western pop and African Zulu rhythms, has exploded onto the international scene and broken through all the barriers in his own country. In France, where he enjoys a massive following, he is fondly called Le Zulu Blanc – the white Zulu. Over three decades, Clegg has sold over five million albums of his brand of crossover music worldwide. He has wowed vast audiences with his audacious live shows and won a number of national and international awards for his music and his outspoken views on apartheid, perspectives on migrant workers in South Africa and the general situation in the world today. Clegg’s history is as bold, colorful and dashing as the rainbow country which he has called home for more than 40 years. Clegg was born in Bacup, near Rochdale, England, in 1953, but was brought up in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Between his mother (a cabaret and jazz singer) and his step-father (a crime reporter who took him into the townships at an early age), Clegg was exposed to a broader cultural perspective than that available to his peers. -

Annual Report

2017/18 ANNUAL REPORT RESILIENCE AND RECOVERY ABOUT US New Vision Printing & Publishing Company Limited started business in March 1986. It is a multimedia business housing newspapers, magazines, internet publishing, televisions, radios, commercial printing, advertising and distribution services. The Company is listed on the Uganda Securities Exchange. Our Vision A globally respected African media powerhouse that advances society Mission To be a market-focused, performance-driven organisation, managed on global standards of operational and financial efficiency Values • Honesty • Innovation • Fairness • Courage • Excellence • Zero tolerance to corruption • Social responsibility 2 VISION GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 INTRODUCTION This is the Annual Report of New Vision Printing & Publishing Company Limited trading as Vision Group for the year ended June 30, 2018. This Annual Report includes financial and non-financial information. It sets out the Company’s strategy, financial, operational, governance, social and environmental performance. The Annual Report also contains the risks and opportunities affecting the Company. The purpose of producing an Annual Report is to give the shareholders an annual view of how the Company has performed and what the Board is striving to do on behalf of the shareholders. 1 TABLE OF contENT Notice of Annual General Meeting 4 Company Profile 5 Business Review 15 Board of Directors 19 Chairperson’s Statement 21 Executive Committee 26 CEO’s Statement 27 Corporate Governance Statement 31 Shareholder Information 42 Proxy Card 47 Sustainability Report 50 Accolades 80 Financial Statements 82 2 VISION GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 LIST OF AcronYMS AGM - Annual General Meeting Annual Report - An annual report is a comprehensive report on a company’s activities including the financial performance throughout the year. -

Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2018

Protection with Serving with Connectivity of Dedicated Heart Sincere Heart Hearts WHOLE HEARTEDNESS Addressing Inadequacies for a Better INITIATIVE Life and Guiding the Emerging Industries CORPORA TE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REPOR T 2018 S TA TE DEVEL OPMENT & INVES Add: International Investment Plaza, 6-6 Fuchengmen North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing, China Postcode: 100034 Tel: +86-10-6657 9001 CORPORATE SOCIAL TMENT CORP Fax: +86-10-6657 9002 RESPONSIBILITY REPORT Website: www.sdic.com.cn Environmental considerations for report publication .,L TD Paper: print on environmentally-friendly paper . Ink: Use environmentally-friendly to reduce air pollution Designed by: Report Introduction Starting from Heart 12 Serving Major National Strategies 14 Contents This report is the eleventh corporate social Supply-side Structural Reform 18 responsibility report released by State Pilot Reform of State-owned Capital 20 Development & Investment Corp., Ltd. Investment Company (hereinafter also referred to as SDIC, the Heart Story: Happy Life for Senior People with Company, the Group or We), systematically Cognitive Disorder in Dawan District Message from the Chairman 02 disclosing responsibility performance of --SDIC Health Jiaqi Senior Apartment 22 SDIC in the aspects of economy, society, and Create Values & Invest in Future environment, and so on. The report covers the period from January 1,2018 to December Operation with Ingenious Heart 26 SDIC Has Successfully 04 31, 2018. Some events took place beyond the Technological Innovation 28 Achieved -

Graduation Ceremonies December 2019

GRADUATION CEREMONIES DECEMBER 2019 CONTENTS Morning Ceremony – Thursday 12 December at 10h00............................................................……...3 Faculties of Health Sciences 1 and Law Afternoon Ceremony – Thursday 12 December at 15h00 ………..............….........…………………22 Faculties of Engineering & the Built Environment and Science Morning Ceremony – Friday 13 December at 09h00 …………................……................…………..48 Faculty of Humanities Afternoon Ceremony – Friday 13 December at 14h00 …….....…………..............................………66 Faculty of Commerce Evening Ceremony – Friday 13 December at 18h00 …………................……................…………..78 Faculty of Health Sciences 2 NATIONAL ANTHEM Nkosi sikelel’ iAfrika Maluphakanyisw’ uphondolwayo, Yizwa imithandazo yethu, Nkosi sikelela, thina lusapho lwayo. Morena boloka etjhaba sa heso, O fedise dintwa la matshwenyeho, O se boloke, O se boloke setjhaba sa heso, Setjhaba sa South Afrika – South Afrika. Uit die blou van onse hemel, Uit die diepte van ons see, Oor ons ewige gebergtes, Waar die kranse antwoord gee, Sounds the call to come together, And united we shall stand, Let us live and strive for freedom, In South Africa our land. 2 FACULTIES OF HEALTH SCIENCES (CEREMONY 1) AND LAW ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS Academic Procession. (The congregation is requested to stand as the procession enters the hall) The Presiding Officer will constitute the congregation. The National Anthem. The University Dedication will be read by a member of the SRC. Musical Item. Welcome by the Master of Ceremonies. The Master of Ceremonies will present Peter Zilla for the award of a Fellowship. The graduands and diplomates will be presented to the Presiding Officer by the Deans of the faculties. The Presiding Officer will congratulate the new graduates and diplomates. The Master of Ceremonies will make closing announcements and invite the congregation to stand. -

36339 12-4 Legala Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 574 Pretoria, 12 April 2013 No. 36339 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE SEE PART C SIEN DEEL C KENNISGEWINGS N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 301359—A 36339—1 2 No. 36339 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 12 APRIL 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. TABLE OF CONTENTS LEGAL NOTICES Page BUSINESS NOTICES.............................................................................................................................................. 11 Gauteng..................................................................................................................................................... 11 KwaZulu-Natal .......................................................................................................................................... -

SAFA Chairperson: Portfolio Committee on Sport and Recreation

SAFA Chairperson: Portfolio Committee on Sport and Recreation Cape Town, 1 November 2019 SAFA A BRIEF BACKGROUND SAFA Governance SAFA GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE SAFA GENERAL COUNCIL 52 Regional Members, 9 Associate Members, 1 Special Member (NSL) SAFA NEC STANDING SAFA COMMITTEES SECRETARIAT DIVISIONS • Football • Football Business • Corporate Services • Legal, Compliance, Membership • Financial Platform SAFA ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE FOOTBALL FOOTBALL BUSINESS CORPORATE SERVICES •Referees •IT •International Affairs •Coaching •Communications •Facilities & Logistics •Nat’l Teams •Commercial •National Technical Ctr •Women’s Football •Events •Safety & Security •Youth Development •Competitions / Leagues •2023 Bid •Futsal •Beach Soccer FINANCE LEGAL, COMPLIANCE, •Procurement MEMBERSHIP •Internal Audit •Financial Platform • Legal / Litigation •Asset Management • Compliance •Fleet Management • Membership •Human Resources • Club Licensing • Integrity SAFA Governance Instruments SAFA STATUTES RULES • National • Competitions • Regional Standard Statutes • Meetings • LFA Statutes • Application of the Statutes • PEC Standard Statutes REGULATIONS -Disciplinary Code -Ethics, Fair Play & Corruption -Electoral Code -Hosting Int’l Matches in SA -Intermediaries Regulations -Club Licensing -Academies Regulations -Referees Code of Conduct -Standing Orders for Meetings -Communications Policy -Player Status & Transfer Regulations ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES • Financial • HR • ICT • Other operational requirements Master Licensor for Football in SA 1. Members (Provincial, -

Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. the Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. The Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli Relatore Ch. Prof. Marco Fazzini Correlatore Ch. Prof. Alessandro Scarsella Laureanda Irene Pozzobon Matricola 828267 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 ABSTRACT When a system of segregation tries to oppress individuals and peoples, struggle becomes an important part in order to have social and civil rights back. Revolutionary poem-songs are to be considered as part of that struggle. This dissertation aims at offering an overview on how South African poet-songwriters, in particular the white Roger Lucey and the black Mzwakhe Mbuli, composed poem-songs to fight against apartheid. A secondary purpose of this study is to show how, despite the different ethnicities of these poet-songwriters, similar themes are to be found in their literary works. In order to investigate this topic deeply, an interview with Roger Lucey was recorded and transcribed in September 2014. This work will first take into consideration poem-songs as part of a broader topic called ‘oral literature’. Secondly, it will focus on what revolutionary poem-songs are and it will report examples of poem-songs from the South African apartheid regime (1950s to 1990s). Its third part will explore both the personal and musical background of the two songwriters. Part four, then, will thematically analyse Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli’s lyrics composed in that particular moment of history. Finally, an epilogue will show how the two songwriters’ perspectives have evolved in the post-apartheid era. -

The United Democratic Front and Political Struggles in the Pietermaritzburg Region, 1983-1991

Mobilization, Conflict and Repression: The United Democratic Front and Political Struggles in the Pietermaritzburg region, 1983-1991. BY NGQABUTHO NHLANGANISO BHEBHE Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Natal. Pietermaritzburg July 1996. DEDICATION To My Family I dedicate this thesis to my father R. Hlanganiso and to my mother K. Rawuwe. To my sisters, Nominenhle and Lindivve,and my brothers, Duduzani, Dumile and Vumani, thanks for your patience and unwavering support. ABSTRACT In the eight years of its existence, from 1983 to 1991, the United Democratic Front had a major impact on the pace and direction ofpolitical struggles in South Africa. The UDF was a loose alliance of organizations, whose strength was determined by the nature of the organizations affiliated to it. This thesis explores the nature of the problems faced by the UDF in the Pietermaritzburg region, and how it sought to respond to them. Chapter one -covers the period from 1976 to 1984. This chapter surveys the political context in which the UDF wasformed, beginning withthe Soweto uprising of 1976, and continuing with the growth of extra-parliamentary organizations in the late 1970s and early 1980s, leading up to the formation of the UDF in 1983. This chapter ends with emergence of organized extra-parliamentary activitiesin Pietermaritzburgin 1984. Chapter two assesses the period between1984 and mid-1986. This was the time when the UDF activists began to mobilize in the region, and it was during this period that UDF structures were set up. -

Unregulated Campaign Spending and It's Impact on Electoral Participants

ALLIANCE FORFOR FINANCE FINANCE MONITORING MONITORING ALLIANCE FORFOR FINANCE FINANCE MONITORING MONITORING Unregulated Campaign Spending and It’s Impact on Electoral Participants in Uganda A Call for Legislative Action and Civic Engagement This report is authored by Eddie Kayinda and Henry Muguzi. It is made possible by support of the Democratic Governance Facility (DGF). The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors & ACFIM, and do not in any way reflect the views of DGF Unregulated Campaign Spending and its Impact on Electoral Participants in Uganda i Alliance for Finance Monitoring (ACFIM) Unregulated Campaign Spending and Its Impact on Electoral Participants in Uganda A Call for Legislative Action and Civic Engagement Authored by: Eddie Kayinda and Henry Muguzi Published By: Alliance for Finance Monitoring (ACFIM - Uganda) Interservice Tower 1st Floor Plot 33 Lumumba Avenue P.O. Box 372016 Kampala Tel: +256 393 217168 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.politicalfinanceafrica.org © Alliance for Finance Monitoring (ACFIM), 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the publisher. The reproduction or use of this publication for purposes of informing, public policy or for academic or charitable purposes is exempted from the restriction. 1 | Unregulated Campaign Spending and its Impact on Electoral Participants in Uganda Alliance for Finance Monitoring (ACFIM) Unregulated Campaign Spending and It’s ImpactUnregulated Campaign on Electoral Participants in Spending and Its Impact on Uganda Electoral Participants in UgandaA Call for Legislative Action A Call for Legislative Action and Civic and Civic Engagement Engagement Authored by: Eddie Kayinda and Henry Muguzi Published By: Alliance for Finance Monitoring (ACFIM - Uganda) Interservice Tower 1st Floor Plot 33 Lumumba Avenue P.O. -

History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902

335 CHAPTER XIV. OPERATIONS IN THE WESTERN TRANSVAAL* (continued). THE PURSUIT AND ESCAPE OF DE WET. The westward drift of hostile forces from Rustenburg, and the surrender of Klerksdorp, made Lord Roberts anxious for the safety of the small isolated posts on the route to Mafeking. A runner was sent to Lieut. -Colonel CO. Hore at Elands River, directing him to call in the detachment of sixty men from Wonderfontein, and warning him to prepare for a siege. The garrisons of Lichtenburg and Zeerust were also ordered to Otto's Hoop. AngloBoerWar.comThese changes, and the presence of a commando near Woodstock, half-way between Magato Nek and Elands River, increased the difficulty of supplying Baden-Powell's force ; and the retention of Rustenburg had to be reconsidered. The Proposed evacuation of this stronghold of the old Boer spirit would mean Rustenburg. a great revival of hope amongst the despondent enemy, and would probably lead to the re-establishment of a new seat of government in the heart of the Transvaal, with consequent per- secution of all who had sided with the British. These views Baden-Powell insistently laid before Lord Roberts, pointing out that the holding of Rustenburg and Zeerust was necessary alike for moral effect, to give sanctuary to peacefully disposed Boers, and to provide bases of supply for mobile columns. In the eyes of the Commander-in-Chief the strategical gain of evacuation outweighed the political loss. He judged that the force at his disposal was best employed in guarding the railway, and in beating the enemy in the field.