The Social Network in Charles Dickens's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PICKWICK PAPERS Required Reading for the Dickens Universe

THE PICKWICK PAPERS Required reading for the Dickens Universe, 2007: * Auden, W. H. "Dingley Dell and the Fleet." The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1962. 407-28. * Marcus, Steven. "The Blest Dawn." Dickens: From Pickwick to Dombey. New York: Basic Books, 1965. 13-53. * Patten, Robert L. Introduction. The Pickwick Papers. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. 11-30. * Feltes, N. N. "The Moment of Pickwick, or the Production of a Commodity Text." Literature and History: A Journal for the Humanities 10 (1984): 203-217. Rpt. in Modes of Production of Victorian Novels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. * Chittick, Kathryn. "The qualifications of a novelist: Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist." Dickens and the 1830s. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. 61-91. Recommended, but not required, reading: Marcus, Steven."Language into Structure: Pickwick Revisited," Daedalus 101 (1972): 183-202. Plus the sections on The Pickwick Papers in the following works: John Bowen. Other Dickens : Pickwick to Chuzzlewit. Oxford, U.K.; New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Grossman, Jonathan H. The Art of Alibi: English Law Courts and the Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2002. Woloch, Alex. The One vs. The Many: Minor Characters and the Space of the Protagonist in the Novel. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2003. 1 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Hillary Trivett May, 1991 Updated by Jessica Staheli May, 2007 For a comprehensive bibliography of criticism before 1990, consult: Engel, Elliot. Pickwick Papers: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1990. CRITICISM Auden, W. H. "Dingley Dell and the Fleet." The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1962. -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Decadence and Renewal in Dickens's Our Mutual Friend

Connotations Vol. 16.1-3 (2006/2007) Decadence and Renewal in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend LEONA TOKER The plot of Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend focuses on the presumed death and ultimate reappearance of the jeune premier, John Harmon. It had been Dickens’s plan to write about “a man, young and perhaps eccentric, feigning to be dead, and being dead to all intents and pur- poses external to himself, and for years retaining the singular view of life and character so imparted” (Forster 2: 291), until, presumably, he could overcome his ghostly detachment. This, indeed, happens owing to the unhurried growth of mutual love between Harmon, posing as the impecunious John Rokesmith, and Bella Wilfer, the woman whose hand in marriage is the condition, according to his eccentric father’s will, for his inheriting the vast property that has meantime gone to the old man’s trusty steward Boffin. Thus Harmon, as well as the erst- while willful and would-be “mercenary” Bella, are reclaimed, re- deemed by love—in the best tradition of the religious humanism that suffuses Dickens’s fiction. As this précis of the plot may suggest, dying and being restored from death are both a metaphor for the literal events of the novel and a symbol of moral regeneration. As usual, Dickens partly desentimen- talizes the up-beat poetic justice by limiting its applicability: Betty Higden’s little grandson whom the Boffins wish to adopt and name John Harmon dies—his death symbolizes or, perhaps, replaces that of the protagonist; the traitor Charley Hexam is ready to march off, unpunished, treading (metaphorically) on corpses (including his father who had literally made a more or less honest living from sal- vaging corpses from the river). -

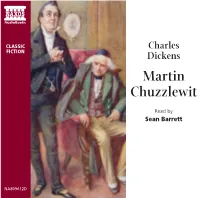

Martin Chuzzlewit

CLASSIC Charles FICTION Dickens Martin Chuzzlewit Read by Sean Barrett NA809612D 1 It was pretty late in the autumn… 5:47 2 ‘Hark!’ said Miss Charity… 6:11 3 An old gentlemen and a young lady… 5:58 4 Mrs Lupin repairing… 4:43 5 A long pause succeeded… 6:21 6 It happened on the fourth evening… 6:16 7 The meditations of Mr Pecksniff that evening… 6:21 8 In their strong feeling on this point… 5:34 9 ‘I more than half believed, just now…’ 5:54 10 You and I will get on excellently well…’ 6:17 11 It was the morning after the Installation Banquet… 4:40 12 ‘You must know then…’ 6:06 13 Martin began to work at the grammar-school… 5:19 14 The rosy hostess scarcely needed… 6:57 15 When Mr Pecksniff and the two young ladies… 5:21 16 M. Todgers’s Commercial Boarding-House… 6:12 17 Todgers’s was in a great bustle that evening… 7:18 18 Time and tide will wait for no man… 4:56 19 ‘It was disinterested too, in you…’ 5:21 20 ‘Ah, cousin!’ he said… 6:28 2 21 The delighted father applauded this sentiment… 5:57 22 Mr Pecksniff’s horse… 5:22 23 John Westlock, who did nothing by halves… 4:51 24 ‘Now, Mr Pecksniff,’ said Martin at last… 6:39 25 They jogged on all day… 5:48 26 His first step, now he had a supply… 7:19 27 For some moments Martin stood gazing… 4:10 28 ‘Now I am going to America…’ 6:49 29 Among these sleeping voyagers were Martin and Mark… 5:01 30 Some trifling excitement prevailed… 5:21 31 They often looked at Martin as he read… 6:05 32 Now, there had been at the dinner-table… 5:05 33 Mr Tapley appeared to be taking his ease… 5:44 34 ‘But stay!’ cried Mr Norris… 4:41 35 Change begets change. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north. -

The History of Riots in London Shows That Persistent Inequality and Injustice Is Always Likely to Breed Periodic Violent Uprisings

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2011/10/25/london-riot-history/ The history of riots in London shows that persistent inequality and injustice is always likely to breed periodic violent uprisings. The August 2011 riots in London prompted many commentators to look back on previous riots in the city and the country to see what common threads, if any, run through outbreaks of public disorder. Jerry White examines the Gordon Riots, the Hyde Park riots of 1855 and the Brixton riots of 1981 and finds that perceived inequalities and injustice in London have and will continue to breed periodic violent uprisings. Riot and London. At first sight the words sit uneasily together, for traditionally London is a city known best for its order, civility and tolerance. Yet in a long history there is space for more than one tradition, and from time to time, every generation or so, rioting in London has challenged the forces of order and stretched them past breaking point. At times London has seemed on the brink of civil war. The history of London’s riots reveals great differences between them. What possible similarity can there be between the August riots of 2011 and, say, the uproar attending the election campaigns and imprisonment of John Wilkes in 1768? It seems not much, though both had some features in common (an element of organisation, for instance, and reckless violence against those seeking to quell the disturbances). But perhaps reflecting further on some of these troubled events, while giving just weight to the very specific triggers that led to rioting in the first place, can begin to unpick those structural features of London life that have caused its tradition of riot to endure over time, and make it likely to continue to do so. -

Barnaby Rudge UNABRIDGED Read by Sean Barrett CLASSIC FICTION

THE Charles Dickens COMPLETE CLASSICS Barnaby Rudge UNABRIDGED Read by Sean Barrett CLASSIC FICTION NAX90912D 1 Preface 8:09 3 Chapter 1 8:16 3 There was another guest... 6:47 4 The heir apparent to the Maypole... 6:54 5 The landlord pausing here... 6:15 6 The man glanced at the parish… 5:07 7 At this point of the narrative... 6:34 8 Chapter 2 5:52 9 Whether the traveller was possessed... 6:51 10 Thus they regarded each other... 6:01 11 Chapter 3 6:11 12 So saying, he raised his face... 6:11 13 With these words, he applied himself... 4:31 14 Chapter 4 5:59 15 After a long and patient contemplation... 5:43 16 Sim Tappertit, among the other fancies... 7:13 17 Although Sim Tappertit had taken no share… 5:23 18 Chapter 5 5:12 19 The widow shook her head. 4:54 20 Chapter 6 5:55 2 21 He took his wig off outright... 5:58 22 The young man smiled... 7:01 23 The raven gave a short, comfortable... 5:13 24 Chapter 7 6:59 25 Poor Gabriel twisted his wig about... 6:14 26 Chapter 8 8:21 27 With these words, he folded his arms again. 8:06 28 To this the novice made rejoinder... 7:13 29 Chapter 9 5:37 30 Miss Miggs deliberated within herself... 7:44 31 Chapter 10 7:19 32 It was spacious enough in all conscience... 7:11 33 John was so very much astonished.. -

The Birth of Subrogation and the War of Independence

The Birth of Subrogation and the War of Independence Question : How did a war between the British and the Americans - and a related riot in London - lead to one of the earliest ever reported subrogation cases? First, some history. Let's go back to the late 1700s when the British were fighting the Americans. The British army, which expected to be victorious in what became the American War of Independence, was very different to the disciplined American army of George Washington. Because they were being outfought, the British soldiers were an unhappy lot, as the following extract from a soldier’s letter home from Charleston, South Carolina, in the spring of 1781 shows. "I wish our ministry could send us a Hercules to conquer these obstinate Americans, whose aversion to the cause of Britain grows stronger every day. If you go into company with any of them occasionally, they are barely civil … They are in general sullen, silent and thoughtful. The King's health they dare not refuse, but they drink it in such a manner as if they expected it would choke them … ; I am heartily tired of this country, and wish myself at home." The uniform they wore was suitable for European warfare but in America it made the troops extremely conspicuous. Their weapons were becoming outdated; they were inaccurate and had only a 50 yard range. The British army lacked knowledge of the terrain, their maps were inadequate and the officers had little concept of the distances involved in such a vast continent. Inevitably, word got back to Britain. -

Political-Legal Geography

Durham E-Theses Understanding the Legal Constitution of a Riot: An Evental Genealogy SCHOFIELD, VANESSA,FAYE How to cite: SCHOFIELD, VANESSA,FAYE (2019) Understanding the Legal Constitution of a Riot: An Evental Genealogy, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13327/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Understanding the Legal Constitution of a Riot: An Evental Genealogy Vanessa Schofield Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography, Durham University 2019 i ii Abstract Understanding the Legal Constitution of a Riot: An Evental Genealogy This thesis considers the constitution of a riot as an event that ruptures. The aim of the thesis is to use an evental theoretical framework to develop a novel understanding of the constitution of a riot, in response to the absence of sustained theoretical reflection on riots, specifically following events in 2011, and England’s so called ‘summer of disorder’. -

Test Your Knowledge: a Dickens of a Celebration!

A Dickens of a Celebration atKinson f. KathY n honor of the bicentennial of Charles dickens’ birth, we hereby Take the challenge! challenge your literary mettle with a quiz about the great Victorian Iwriter. Will this be your best of times, or worst of times? Good luck! This novel was Dickens and his wife, This famous writer the first of Dickens’ Catherine, had this was a good friend 1 romances. 5 many children; 8 of Dickens and some were named after his dedicated a book to him. (a) David Copperfield favorite authors. (b) Martin Chuzzlewit (a) Mark twain (c) Nicholas Nickleby (a) ten (b) emily Bronte (b) five (c) hans christian andersen (c) nine Many of Dickens’ books were cliffhangers, Where was 2 published in monthly The conditions of the Dickens buried? installments. In 1841, readers in working class are a Britain and the U.S. anxiously 9 common theme in awaited news of the fate of the 6 (a) Portsmouth, england Dickens’ books. Why? pretty protagonist in this novel. (where he was born) (a) he had to work in a (b) Poet’s corner, westminster (a) Little Dorrit warehouse as a boy to abbey, London (b) A Tale of Two Cities help get his family out of (c) isles of scilly (c) The Old Curiosity Shop debtor’s prison. (b) his father worked in a livery and was This amusement This was an early mistreated there. park in Chatham, pseudonym used (c) his mother worked as England, is 3 by Dickens. a maid as a teenager and named10 after Dickens. -

Charles Dickens's “A Christmas Carol”

CHARLES DICKENS’S “A CHRISTMAS CAROL” A lesson which emphasized the importance of imaginative sympathy, and of that `Fancy' which is to be discovered in the true use of memory. Memories of the past. Memories of childhood (DAVID COPPERFIELD. is a heavily fictionalized but emotionally truthful account of his own childhood). Memory was a form of inspiration, therefore, which linked past and present, unified humankind with the shared recollection of sorrow, and imparted a meaning to life....' Dicken's theme is man's inhumanity to child, and his social target is the new workhouses established on the Benthamite principles (see for example OLIVER TWIST (1837-1838)…. If in his later works his characters became less lively, this is less because they are deeper than because they have to fit into a social vision that is increasingly despairing. When critics accused him of melodrama and sentimentality he would characteristically reply that everything he wrote was true, it represented the way of the world. That in a sense is the theme of this introduction to Charles Dickens; there will be no attempt to provide a simple biography, but rather to outline the ways in which the very texture of Dickens’s life affected the nature of his fiction. Dickens was changed by his novels and by the creatures who stalk through them, because in the act of creating them he came to realise more of his own possibilities: 1. The boy who worked in a crumbling warehouse became the novelist who insistently recorded the presence of dark and crumbling buildings which haunt his fiction.