Welfare Queens and White Trash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

" Ht Tr H" : Trtp Nd N Nd Tnf P Rhtn Th

ht "ht Trh": trtp nd n ndtn f Pr ht n th .. nnl Ntz, tth r Minnesota Review, Number 47, Fall 1996 (New Series), pp. 57-72 (Article) Pblhd b D nvrt Pr For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mnr/summary/v047/47.newitz.html Access provided by Middlebury College (11 Dec 2015 16:54 GMT) Annalee Newitz and Matthew Wray What is "White Trash"? Stereotypes and Economic Conditions of Poor Whites in the U.S. "White trash" is, in many ways, the white Other. When we think about race in the U.S., oftentimes we find ourselves constrained by cat- egories we've inherited from a kind of essentialist multiculturalism, or what we call "vulgar multiculturalism."^ Vulgar multiculturalism holds that racial and ethic groups are "authentically" and essentially differ- ent from each other, and that racism is a one-way street: it proceeds out of whiteness to subjugate non-whiteness, so that all racists are white and all victims of racism are non-white. Critical multiculturalism, as it has been articulated by theorists such as those in the Chicago Cultural Studies Group, is one example of a multiculturalism which tries to com- plicate and trouble the dogmatic ways vulgar multiculturalism has un- derstood race, gender, and class identities. "White trash" identity is one we believe a critical multiculturalism should address in order to further its project of re-examining the relationships between identity and social power. Unlike the "whiteness" of vulgar multiculturalism, the whiteness of "white trash" signals something other than privilege and social power. -

10-Welfare-Viewing Guide.Pdf

1 | AN INTRODUCTION TO WHAT I HEAR WHEN YOU SAY Deeply ingrained in human nature is a tendency to organize, classify, and categorize our complex world. Often, this is a good thing. This ability helps us make sense of our environment and navigate unfamiliar landscapes while keeping us from being overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information and experiences. When we apply this same impulse to social interactions, however, it can be, at best, reductive and, at worst, dangerous. Seeing each other through the lens of labels and stereotypes prevents us from making authentic connections and understanding each other’s experiences. Through the initiative, What I Hear When You Say ( WIHWYS ), we explore how words can both divide and unite us and learn more about the complex and everchanging ways that language shapes our expectations, opportunities, and social privilege. WIHWYS ’s interactive multimedia resources challenge what we think we know about race, class, gender, and identity, and provide a dynamic digital space where we can raise difficult questions, discuss new ideas, and share fresh perspectives. 1 | Introduction WELFARE I think welfare queen is an oxymoron. I can’t think of a situation where a queen would be on welfare. “ Jordan Temple, Comedian def•i•ni•tion a pejorative term used in the U.S. to refer to women who WELFARE QUEEN allegedly collect excessive welfare payments through fraud or noun manipulation. View the full episode about the term, Welfare Queen http://pbs.org/what-i-hear/web-series/welfare-queen/ A QUICK LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF U.S. -

© 2015 Kasey Lansberry All Rights Reserved

© 2015 KASEY LANSBERRY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER, RACE, AND PLACE IN WELFARE PARTICIPATION: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WELFARE-TO-WORK PROGRAMS IN OHIO AND NORTH CAROLINA COUNTIES A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty at the University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Kasey D. Lansberry August, 2015 THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER, RACE, AND PLACE IN WELFARE PARTICIPATION: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WELFARE-TO-WORK PROGRAMS IN OHIO AND NORTH CAROLINA COUNTIES Kasey Lansberry Dissertation Approved: Accepted: ________________________________ ____________________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Tiffany Taylor Dr. Matthew Lee ________________________________ ____________________________________ Co-Advisor or Faculty Reader Dean of the College Dr. Kathryn Feltey Dr. Chand Midha ________________________________ ____________________________________ Committee Member Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Adrianne Frech Dr. Chand Midha ________________________________ ____________________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Janette Dill ________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Nicole Rousseau ________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Pamela Schulze ii ABSTRACT Welfare participation has been a longstanding issue of public debate for over the past 50 years, however participation remains largely understudied in welfare literature. Various public policies, racial discrimination, the war on poverty, fictitious political depictions of the “welfare queen”, and a call for more stringent eligibility requirements all led up to the passage of welfare reform in the 1990s creating the new Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) program. Under the new welfare program, work requirements and time limits narrowed the field of eligibility. The purpose of this research is to examine the factors that influence US welfare participation rates among the eligible poor in 2010. -

Re-Presenting Black Masculinities in Ta-Nehisi Coates's

Re-Presenting Black Masculinities in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me by Asmaa Aaouinti-Haris B.A. (Universitat de Barcelona) 2016 THESIS/CAPSTONE Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HUMANITIES in the GRADUATE SCHOOL of HOOD COLLEGE April 2018 Accepted: ________________________ ________________________ Amy Gottfried, Ph.D. Corey Campion, Ph.D. Committee Member Program Advisor ________________________ Terry Anne Scott, Ph.D. Committee Member ________________________ April M. Boulton, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ________________________ Hoda Zaki, Ph.D. Capstone Advisor STATEMENT OF USE AND COPYRIGHT WAIVER I do authorize Hood College to lend this Thesis (Capstone), or reproductions of it, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ii CONTENTS STATEMENT OF USE AND COPYRIGHT WAIVER…………………………….ii ABSTRACT ...............................................................................................................iv DEDICATION………………………………………………………………………..v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………….....vi Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………….…2 Chapter 2: Black Male Stereotypes…………………………………………………12 Chapter 3: Boyhood…………………………………………………………………26 Chapter 4: Fatherhood……………………………………………………………....44 Chapter 5: Conclusion…………………………………………………………...….63 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………………….69 iii ABSTRACT Ta-Nehisi Coates’s memoir and letter to his son Between the World and Me (2015)—published shortly after the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement—provides a rich and diverse representation of African American male life which is closely connected with contemporary United States society. This study explores how Coates represents and explains black manhood as well as how he defines his own identity as being excluded from United States society, yet as being central to the nation. Coates’s definition of masculinity is analyzed by focusing on his representations of boyhood and fatherhood. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

The N-Word : Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings Anne V

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2009 The N-word : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings Anne V. Benfield Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Benfield, Anne V., "The -wN ord : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings" (2009). Honors Theses. 1433. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1433 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The N-Word: Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings By Anne V. Benfield * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Sociology UNION COLLEGE June, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Literature Review Etymology 7 Early Uses 8 Fluidity in the Twentieth Century 11 The Commercialization of Nigger 12 The Millennium 15 Race as a Determinant 17 Gender Binary 19 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 23 Generational Difference 25 Chapter Two: Methodology Sociological Theories 29 W.E.B DuBois’ “Double-Consciousness” 34 Qualitative Research Instrument: Focus Groups 38 Chapter Three: Results and Discussion Demographics 42 Generational Difference 43 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 47 Gender Binary 51 Race as a Determinant 55 The Ambiguity of Nigger vs. -

Disciplinary Gestures in Charles Kingsley´S at Last : a Christmas in the West Indies (1871) Revista Mexicana Del Caribe, Vol

Revista Mexicana del Caribe ISSN: 1405-2962 [email protected] Universidad de Quintana Roo México Wahab, Amar Re-writing colonized subjects: disciplinary gestures in Charles Kingsley´s at last : a christmas in the west Indies (1871) Revista Mexicana del Caribe, vol. VIII, núm. 16, 2003, pp. 133-178 Universidad de Quintana Roo Chetumal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12801605 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto RE-WRITING COLONIZED SUBJECTS: DISCIPLINARY GESTURES IN CHARLES KINGSLEY’S AT LAST: A CHRISTMAS IN THE WEST INDIES (1871) AMAR WAHAB* University of Toronto Abstract The Victorian period of British travel writing in the “tropicalized” world distinguished itself from early nineteenth-century travel due partic- ularly to changing demands for re-inventing British control in the post-emancipation period. This article unpacks the textual and visual representations of Negroes and Coolies in nineteenth-century Trinidad in the travelogue of British natural historian, Charles Kingsley, high- lighting the discursive powers of these representations in re-stabilizing British rule and order in the colony. Kingsley’s re-writing of colonized subjects cannot be disconnected from the re-definition and re-deploy- ment of ideas of race and rule across the British Empire, especially in the context of post-emancipation labour shortages, the rise of the black subject and colonial anxieties about the “Negro character”. -

The Negro Is Paid to Dance

Diálogo Volume 8 Number 1 Article 17 2004 The Negro is Paid to Dance Matilde E. López Karin Killian Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation López, Matilde E. and Killian, Karin (2004) "The Negro is Paid to Dance," Diálogo: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 17. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol8/iss1/17 This Rincón Creativo is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Negro is Paid to Dance Cover Page Footnote This article is from an earlier iteration of Diálogo which had the subtitle "A Bilingual Journal." The publication is now titled "Diálogo: An Interdisciplinary Studies Journal." This rincón creativo is available in Diálogo: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol8/iss1/17 Art by Fernando Llort. isThePaid Negro to Dance Image from stationary, provided by Claudia Morales Haro A Short Story by Matilde Elena Lopez Translated by Karin Killian Lima, Peru This is the history of a sad man, or better put, the history of a The only thing I remember about my father is a strong tail sad Negro who is now sadder still. I feel in my heart as though Jamaican who spoke only English. "British, British. Panama is I have been painted with pitch. I am drowning in a cesspool. I of no importance to me," he used to say. -

Introduction

Introduction R. J. Ellis One of the most influential books ever written, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly was also one of the most popular in the nineteenth century. Stowe wrote her novel in order to advance the anti-slavery cause in the ante-bellum USA, and rooted her attempt to do this in a ‘moral suasionist’ approach — one designed to persuade her US American compatriots by appealing to their God-given sense of morality. This led to some criticism from immediate abolitionists — who wished to see slavery abolished immediately rather than rely upon [per]suasion. Uncle Tom's Cabin was first published in 1852 as a serial in the abolitionist newspaper National Era . It was then printed in two volumes in Boston by John P. Jewett and Company later in 1852 (with illustrations by Hammatt Billings). The first printing of five thousand copies was exhausted in a few days. Title page, with illustration by Hammatt Billings, Uncle Tom’s Cabin Vol. 1, Boston, John P. Jewett and Co., 1852 During 1852 several reissues were printed from the plates of the first edition; each reprinting also appearing in two volumes, with the addition of the words ‘Tenth’ to ‘One Hundred and Twentieth Thousand’ on the title page, to distinguish between each successive re-issue. Later reprintings of the two-volume original carried even higher numbers. These reprints appeared in various bindings — some editions being quite lavishly bound. One-volume versions also appeared that same year — most of these being pirated editions. From the start the book attracted enormous attention. -

Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 66–75 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2391 Article “Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks Margarethe Kusenbach Department of Sociology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 1 August 2019 | Accepted: 4 October 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract In the United States, residents of mobile homes and mobile home communities are faced with cultural stigmatization regarding their places of living. While common, the “trailer trash” stigma, an example of both housing and neighbor- hood/territorial stigma, has been understudied in contemporary research. Through a range of discursive strategies, many subgroups within this larger population manage to successfully distance themselves from the stigma and thereby render it inconsequential (Kusenbach, 2009). But what about those residents—typically white, poor, and occasionally lacking in stability—who do not have the necessary resources to accomplish this? This article examines three typical responses by low-income mobile home residents—here called resisting, downplaying, and perpetuating—leading to different outcomes regarding residents’ sense of community belonging. The article is based on the analysis of over 150 qualitative interviews with mobile home park residents conducted in West Central Florida between 2005 and 2010. Keywords belonging; Florida; housing; identity; mobile homes; stigmatization; territorial stigma Issue This article is part of the issue “New Research on Housing and Territorial Stigma” edited by Margarethe Kusenbach (University of South Florida, USA) and Peer Smets (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands). © 2020 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

How Social Normativity Negatively Impacts White Health

White Privilege vs. White Invisibility and the Manifestation of White Fragility: How Social Normativity Negatively Impacts White Health By Sharon Zipporah Champion Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Medicine, Health, and Society May, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jonathan M. Metzl, M.D., Ph.D. Dominique P. Béhague, Ph.D. Hector F. Myers, Ph.D. To my bedrock of a family, my wise friends, my infinitely supportive fiancé, To those who have passed on that have paved the road to be less rocky for my travels. I love you all. Finally, to those who have suffered under the weight of whiteness, who have been rendered silent by its violent pervasiveness in society, whose lives have been troubled and cut short by the waif-like fragility of it, I hear you, I see you, and I hope this does some slight justice for the strange fruit still hanging from the trees. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not exist without my adviser, Dr. Jonathan Metzl, with his unending enthusiasm and support of my work through this process. Thank you for answering long distance phone calls, frantic late night emails, and nervous questions after class. This extends to my thesis committee Dr. Dominique Béhague and Dr. Hector Myers, who graciously worked with me and gave infinitely helpful advice to develop this thesis. I would be still mired in my writing struggles without you all. To the Vanderbilt Center for Medicine, Health, and Society, I have grown and learned immensely through this Master’s program and thank you fervently for this scholastic opportunity to flex my mind. -

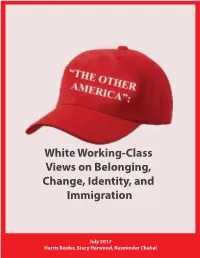

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration July 2017 Harris Beider, Stacy Harwood, Kusminder Chahal Acknowledgments We thank all research participants for your enthusiastic participation in this project. We owe much gratitude to our two fabulous research assistants, Rachael Wilson and Erika McLitus from the University of Illinois, who helped us code all the transcripts, and to Efadul Huq, also from the University of Illinois, for the design and layout of the final report. Thank you to Open Society Foundations, US Programs for funding this study. About the Authors Harris Beider is Professor in Community Cohesion at Coventry University and a Visiting Professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Stacy Anne Harwood is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Kusminder Chahal is a Research Associate for the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University. For more information Contact Dr. Harris Beider Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations Coventry University, Priory Street Coventry, UK, CV1 5FB email: [email protected] Dr. Stacy Anne Harwood Department of Urban & Regional Planning University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 111 Temple Buell Hall, 611 E. Lorado Taft Drive Champaign, IL, USA, 61820 email: [email protected] How to Cite this Report Beider, H., Harwood, S., & Chahal, K. (2017). “The Other America”: White working-class views on belonging, change, identity, and immigration. Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University, UK. ISBN: 978-1-84600-077-5 Photography credits: except when noted all photographs were taken by the authors of this report.