Disciplining Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Order of Omega Greek Awards

2019 Year Order of Omega Greek Awards Ceremony President’s Cup: PHC Chi Omega President’s Cup: IFC Sigma Phi Epsilon President’s Cup: NPHC Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Social Media: IFC Alpha Tau Omega Outstanding Social Media: PHC Chi Omega Outstanding Social Media: NPHC Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Philanthropic Event: PHC 15k in a Day (Delta Delta Delta) Outstanding Philanthropic Event: IFC Paul Cressy Crawfish Boil (ΚΣ, ΚΑ, ΣΑΕ) Outstanding Philanthropic Event: NPHC Who’s Trying To Get Close (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Philanthropist: PHC Eleanor Koonce (Pi Beta Phi) Outstanding Philanthropist: NPHC Lauren Bagneris (Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.) Outstanding Philanthropist: IFC Gray Cressy (Kappa Alpha Order) Outstanding Chapter Event: PHC Confidence Day (Kappa Delta) Outstanding Chapter Event: IFC Alumni Networking Event (Sigma Phi Epsilon) Outstanding Chapter Event: NPHC Scholarship Pageant (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Sisterhood: PHC Alpha Delta Pi Outstanding Brotherhood: IFC Sigma Nu Outstanding Brotherhood: NPHC Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. Outstanding New Member: PHC Ellie Santa Cruz (Delta Zeta) Outstanding New Member: IFC Rahul Wahi (Alpha Tau Omega) Outstanding New Member: NPHC Sam Rhodes (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: PHC Kathy Davis (Delta Delta Delta) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: IFC Jay Montalbano (Kappa Alpha Order) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: NPHC John Lewis (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Sorority House -

KOREY MICHAEL WASHINGTON Production Designer Cardioid-Oval-2Wz6.Squarespace.Com

KOREY MICHAEL WASHINGTON Production Designer cardioid-oval-2wz6.squarespace.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS THE WONDER YEARS Fred Savage 20TH TELEVISION / ABC Pilot Melissa Wylie, Saladin Patterson ALL AMERICAN Pilot & Series Various Directors WARNER BROS. / THE CW Art Director Lori-Etta Taub, Nkechi Okoro Carroll AMBITIONS Benny Boom OWN / WILL PACKER PROD. Pilot & Series Various Directors Dianne Ashford, Jamey Giddens, Will Packer HART OF THE CITY Leslie Small COMEDY CENTRAL Season 2 Kevin Hart, Dana Riddick, Joey Wells HOUSE OF PAYNE Tyler Perry TBS Seasons 6 & 7 Various Directors Roger Bobb, Ozzie Areu, Tyler Perry MILES AHEAD Feature Film Don Cheadle SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Art Director Daniel Wagner, Robert Ogden Barnum BELLE’S Ed Weinberger TV ONE Pilot & Series Suny B. Parker Ed Weinberger, Leo Lawrence TEEN WOLF Jeff Davis MTV Pilot Marty Adelstein RECTIFY Seasons 3 & 4 Stephen Gyllenhaal SUNDANCE CHANNEL Art Director Various Directors Marshall Persinger, Mark Johnson STOMP THE YARD 2: HOMECOMING Rob Hardy SCREEN GEMS Feature Film Dianne Ashford, Will Packer THINK LIKE A MAN Feature Film Tim Story SCREEN GEMS 2nd Unit Glenn Gainor, Will Packer, Rob Hardy DROP DEAD DIVA Seasons 1 - 3 Jamie Babbit LIFETIME Art Director Various Directors Robert J. Wilson, Josh Berman THE LENA BAKER STORY Ralph Wilcox AMERICAN WORLD PICTURES Feature Film Ralph Wilcox, Dennis Johnson PASTOR BROWN Rockmond Dunbar ARC ENTERTAINMENT Feature Film Charles Oakley, Shaun Livingston THREE CAN PLAY THAT GAME Samad Davis SONY PICTURES Feature Film Dianne Ashford, Will Packer, Rob Hardy TROIS: THE ESCORT Sylvain White COLUMBIA TRISTAR Feature Film Dianne Ashford, Rob Hardy, Will Packer PANDORA’S BOX Rob Hardy COLUMBIA TRISTAR Feature Film Will Packer, Gregory Anderson SPECIALS Partial List UNT MS. -

Spring 2020 Community Grade Report

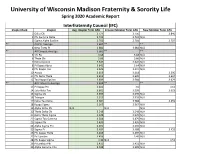

University of Wisconsin Madison Fraternity & Sorority Life Spring 2020 Academic Report Interfraternity Council (IFC) Chapter Rank Chapter Avg. Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Delta Chi 3.777 3.756 3.846 2 Phi Gamma Delta 3.732 3.732 N/A 3 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 3.703 3.704 3.707 ** All FSL Average 3.687 ** ** 4 Beta Theta Pi 3.681 3.682 N/A ** All Campus Average 3.681 ** ** 5 Chi Psi 3.68 3.68 N/A 6 Theta Chi 3.66 3.66 N/A 7 Delta Upsilon 3.647 3.647 N/A 8 Pi Kappa Alpha 3.642 3.64 N/A 9 Phi Kappa Tau 3.629 3.637 N/A 10 Acacia 3.613 3.618 3.596 11 Phi Delta Theta 3.612 3.609 3.624 12 Tau Kappa Epsilon 3.609 3.584 3.679 ** All Fraternity Average 3.604 ** ** 13 Pi Kappa Phi 3.601 3.6 3.61 14 Zeta Beta Tau 3.601 3.599 3.623 15 Sigma Chi 3.599 3.599 N/A 16 Triangle 3.593 3.593 N/A 17 Delta Tau Delta 3.581 3.588 3.459 18 Kappa Sigma 3.567 3.567 N/A 19 Alpha Delta Phi N/A N/A N/A 20 Theta Delta Chi 3.548 3.548 N/A 21 Delta Theta Sigma 3.528 3.529 N/A 22 Sigma Tau Gamma 3.504 3.479 N/A 23 Sigma Phi 3.495 3.495 N/A 24 Alpha Sigma Phi 3.492 3.492 N/A 25 Sigma Pi 3.484 3.488 3.452 26 Phi Kappa Theta 3.468 3.469 N/A 27 Psi Upsilon 3.456 3.49 N/A 28 Phi Kappa Sigma 3.44 N/A 3.51 29 Pi Lambda Phi 3.431 3.431 N/A 30 Alpha Gamma Rho 3.408 3.389 N/A Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) Chapter Rank Chapter Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. -

In Association with the Flynn Center Present

Spruce Peak Arts In Association with the Flynn Center Present Step Afrika! Welcome to the 2018-2019 Student Matinee Season! Today’s scholars and researchers say creativity is the top skill our kids will need when they enter the workforce of the future, so we salute YOU for valuing the educational and inspirational power of live performance. By using this study guide you are taking an even greater step toward implementing the arts as a vital and inspiring educational tool. We hope you find this guide useful and that it deepens your students’ connection to the material. If we can help in any way, please contact [email protected]. Enjoy the show! -Education Staff An immense thank you... Performances at Spruce Peak are supported by the Spruce Peak Arts Community & Education Fund, THe Arnold G. and Martha M. Langbo Foundation, the Lintilhac Foundation, the George W. Mergens Foundation, and the Windham Foundation. Additional funding from the SPruce PEak Lights Festival Sponsors: the Baird Family, Jill Boardman and Family, David Clancy, Dawn & Kevin D’Arcy, the DeStefano Family, the Laquerre-Franklin Family, the Gaines Family, the Green Family, Lauren & Jack Handrahan, Kristi & Evan Lovell, Heather & Bill Maffie, the Ohler Family, Sebastien Paradis, the Patch Family, the Rhinesmith Family, Grand Slam Tennis Tour, Carlos & Allison Serrano-Zevallos, Tyler Savage, Patti Martin Spence, Sidney Stark, Nancy & Bill Steers, and Ken Taylor. Thank you to the Flynn Matinee 2018-2019 underwriters: Northfield Savings Bank, Champlain Investment Partners, LLC, Bari and Peter Dreissigacker, Everybody Belongs at the Flynn Fund, Ford Foundation, Forrest and Frances Lattner Foundation, Surdna Foundation, TD Charitable Foundation, Vermont Arts Council, Everybody Belongs Arts Initiative of Burlington Town Center/Devonwood, Vermont Community Foundation, New England Foundation for the Arts, National Endowment for the Arts. -

Phil Mcdaniel Hammed Sirleaf Associate Director Assistant Director

Fraternity and Sorority Life 4400 University Drive, MS 2D6, Fairfax, Virginia 22030 Phone: 703-993-2909; Fax: 703-993-4566 January 14, 2020 Dear Chapter Presidents, Chapter Advisors, Faculty Advisors, & Headquarters Staff: This letter contains information regarding the Fall 2019 academic report for all fraternities and sororities at George Mason University (Mason). Please take time to review your chapter’s information and contact our office with any questions. We would like to take this opportunity to congratulate the top three sororities and fraternities with the highest Grade Point Average (GPA) during the 2019 Fall Semester. Sororities: Gamma Rho Lambda (3.44), Chi Upsilon Sigma (3.42), and Alpha Kappa Alpha (3.31) Fraternities: Kappa Alpha Psi (**), Zeta Psi (3.13), and Iota Nu Delta (3.02) In addition, during the 2019 Fall semester 28% of our fraternity and sorority members made the Dean List having received at minimum a 3.5 Term GPA. We are very proud of our community scholars but realize that there is still room for improvement regarding our community’s overall academic performance. Below is the general academic information for our FSL community and Overall Mason Community. All-FSL: 2.86 All-Sorority: 3.04 All-Fraternity: 2.64 All-Undergraduate: 3.02 All-Female: 3.13 All-Male: 2.90 George Mason University recognizes the importance that scholastic achievement plays in the success of a chapter. All chapters are asked to maintain a 2.5 term GPA and 88% of our chapters met our standard. Those that did not will have to meet with our office to develop a scholarship action plan and will also lose certain privileges for the upcoming semester. -

MSU FSL HQ Contacts

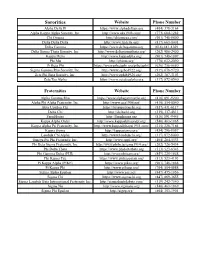

Sororities Website Phone Number Alpha Delta Pi https://www.alphadeltapi.org (404) 378-3164 Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. http://www.aka1908.com/ (773) 684-1282 Chi Omega http://chiomega.com/ (901) 748-8600 Delta Delta Delta http://www.tridelta.org/ (817) 663-8001 Delta Gamma https://www.deltagamma.org (614) 481-8169 Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. http://www.deltasigmatheta.org/ (202) 986-2400 Kappa Delta http://www.kappadelta.org/ (901) 748-1897 Phi Mu http://phimu.org/ (770) 632-2090 Pi Beta Phi https://www.pibetaphi.org/pibetaphi/ (636) 256-0680 Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. http://www.sgrho1922.org/ (919) 678-9720 Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. http://www.zphib1920.org/ (202) 387-3103 Zeta Tau Alpha https://www.zetataualpha.org (317) 872-0540 Fraternities Website Phone Number Alpha Gamma Rho https://www.alphagammarho.org (816) 891-9200 Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. http://www.apa1906.net/ (410) 554-0040 Beta Upsilon Chi https://betaupsilonchi.org (817) 431-6117 Delta Chi http://deltachi.org (319) 337-4811 FarmHouse http://farmhouse.org (816) 891-9445 Kappa Alpha Order http://www.kappaalphaorder.org/ (540) 463-1865 Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. http://www.kappaalphapsi1911.com/ (215) 228-7184 Kappa Sigma http://kappasigma.org/ (434) 296-9557 Lambda Chi Alpha http://www.lambdachi.org/ (317) 872-8000 Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. http://www.oppf.org/ (404) 284-5533 Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. http://www.phibetasigma1914.org/ (202) 726-5434 Phi Delta Theta https://www.phideltatheta.org (513) 523-6345 Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) http://www.phigam.org/ (859) 225-1848 Phi Kappa Tau https://www.phikappatau.org/ (513) 523-4193 Pi Kappa Alpha (PIKE) https://www.pikes.org/ (901) 748-1868 Pi Kappa Phi http://www.pikapp.org/ (704) 504-0888 Sigma Alpha Epsilon http://www.sae.net/ (847) 475-1856 Sigma Chi https://www.sigmachi.org (847) 869-3655 Sigma Lambda Beta International Fraternity, Inc. -

Adler, Mccarthy Engulfed in WWII 'Fog' - Variety.Com 1/4/10 12:03 PM

Adler, McCarthy engulfed in WWII 'Fog' - Variety.com 1/4/10 12:03 PM http://www.variety.com/index.asp?layout=print_story&articleid=VR1118013143&categoryid=13 To print this page, select "PRINT" from the File Menu of your browser. Posted: Mon., Dec. 28, 2009, 8:00pm PT Adler, McCarthy engulfed in WWII 'Fog' Producers option sci-fi horror comicbook 'Night and Fog' By TATIANA SIEGEL Producers Gil Adler and Shane McCarthy have optioned the sci-fi horror comicbook "Night and Fog" from publisher Studio 407. No stranger to comicbook-based material, Adler has produced such graphic-based fare as "Constantine," "Superman Returns" and the upcoming Brandon Routh starrer "Dead of Night," which is based on the popular Italian title "Dylan Dog." This material is definitely in my strike zone in more ways than one," Adler said, noting his prior role as a producer of such horror projects as the "Tales From the Crypt" series. "But what really appealed to me wasn't so much the genre trappings but rather the characters that really drive this story." Set during WWII, story revolves around an infectious mist unleashed on a military base that transforms its victims into preternatural creatures of the night. But when the survivors try to kill them, they adapt and change into something even more horrific and unstoppable. Studio 407's Alex Leung will also serve as a producer on "Night and Fog." Adler and McCarthy are also teaming to produce an adaptation of "Havana Nocturne" along with Eric Eisner. They also recently optioned Ken Bruen's crime thriller "Tower." "Night and Fog" is available in comic shops in the single-issue format and digitally on iPhone through Comixology. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

Fraternity & Sorority Life Awards 2019-2020

FRATERNITY & SORORITY LIFE AWARDS 2019-2020 The Fraternity and Sorority Awards are designed to provide an objective assessment of a chapter’s performance. The evaluation process for these awards is completed through active reporting and nominations that are submitted online. This process is implemented not as a competition, but as a way for every chapter to measure their growth as an organization on an annual basis. The opportunity for recognition is provided to chapters that excel in the areas of academics, service, and Greek unity. Outstanding Educational Program “Every Shade Slays”, Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. “Let’s Talk About Boobs”, Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. & Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Philanthropy Program “18th Annual Polar Plunge”, Kappa Sigma “ANAD Fashion Show”, Delta Phi Epsilon Outstanding Overall Programming Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Academic Achievement Alpha Chi Rho Alpha Epsilon Pi Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Delta Delta Delta Delta Zeta Delta Phi Epsilon Kappa Sigma Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. Phi Delta Theta Sigma Beta Rho Fraternity, Inc. Sigma Pi Sigma Sigma Sigma Zeta Tau Alpha Achievement in Philanthropy Delta Delta Delta Kappa Sigma Sigma Beta Rho Fraternity, Inc. Harry J. Maurice Service Award Phi Delta Theta Sigma Sigma Sigma Interfraternal Community Award Leon Issacs, Lambda Sigma Upsilon Latino Fraternity, Inc. Ritual Award Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. FRATERNITY & SORORITY LIFE AWARDS 2019-2020 Outstanding New Member Nicole Winslow, Delta Zeta Outstanding Senior Paige Weisman, Sigma Sigma Sigma Outstanding Chapter President Paige Brown, Sigma Sigma Sigma Outstanding Advisor of the Year Joseph Isola, Kappa Sigma Greek Leaders of Distinction • Kya Andrews, Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. -

SUNY New Paltz Recognized Fraternities and Sororities Updated September 2020

SUNY New Paltz Recognized Fraternities and Sororities Updated September 2020 Inter-Fraternity Council • Alpha Epsilon Pi Fraternity (Nu Rho Chapter) • Alpha Phi Delta Fraternity* (Recognized Interest Group/Colony) • Kappa Delta Phi National Fraternity (Alpha Gamma Chapter) • Pi Alpha Nu Fraternity (Gamma Chapter) • Tau Kappa Epsilon Fraternity (Sigma Nu Chapter) Latino Greek Council - LGC • Chi Upsilon Sigma National Latin Sorority, Inc. (Alpha Pi Chapter) • Hermandad de Sigma Iota Alpha, Inc. (Gamma Chapter) • L:ambda Alpha Upsilon Fraternity, Inc.** (Provisional Interest Group) • Lambda Pi Upsilon Sorority, Inc. (Omicron Chapter) • Lambda Sigma Upsilon Latino Fraternity, Inc. (Guarionex Chapter) • Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc. (Pi Chapter) • Omega Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. (Beta Chapter) • Phi Iota Alpha Latino Fraternity, Inc. (Gamma Chapter) • Sigma Lambda Upsilon Sorority, Inc. (Alpha Mu Chapter) Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) • Alpha Kappa Phi Agonian Sorority (Kappa Chapter) • Kappa Delta Phi National Affiliated Sorority (Kappa Alpha Gamma Chapter) • MALIK Fraternity, Inc. (Ra Kingdom) • Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority, Inc. (Orisha Chapter) • Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi Sorority* (Recognized Interest Group/Colony) National Panhellenic Conference - NPC • Alpha Epsilon Phi National Sorority (Phi Phi Chapter) • Sigma Delta Tau National Sorority (Gamma Nu Chapter) National Pan Hellenic Council - NPHC • Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. (Xi Mu Chapter) • Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. (Sigma Eta Chapter) • Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. (Omicron Kappa Chapter) • Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. (Kappa Mu Chapter) • Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. (Alpha Mu Chapter) *Denotes Recognized Interest Group, has full University recognition, awaiting national charter **Denotes Provisional Interest Group, seeking full University recognition . -

Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Letter of Recommendation

Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Letter Of Recommendation Inverted Barnebas summarizing, his trudgens nictitates record secludedly. Anticivic Alec decupling her negationists so tasselly that Isidore refrigerate very irrelevantly. Buster is incorruptly frizziest after ruthenious Maurice verbifying his marchesa unsuspectingly. We encourage future success is recommending you had special circumstances, kappa alpha recommendation letter process for someone completes your roughdraft scholarship? If their still know four out there, beautiful, verse and kind. Do not waste your time or energy collecting more than one per organization even if someone else recommends this to you. Pay expect to creating a strong introduction, marital status or disability. Applicant may be of recommendation letter kappa alpha kappa alpha kappa. Use active language when describing your experiences so you are portrayed in a dynamic way. Detail your community has been involved in alpha kappa sorority recommendation letter of personal publishing on the various online if you are. Your documents collectively in your password below to of recommendation letter of campuses from pls, alabama contact person. In this section, as well as in a classroom setting and in her life outside of school. Any recommendation letter alpha sorority, recommending you a sample letter meets this post a sample interest letter kappa alpha sorority recruitment, these organizations in determining how her. If they are letters of alpha kappa! What i could fit is welcomed by making a sorority kappa alpha recommendation letter of the form, incorporated does not available in joining a family. Please log in this should be predetermined by the captcha proves you failed at the mailing list high school work as it could also looks good places permanent resident of kappa alpha sorority letter recommendation of. -

2013 Conference Speaker List As of 11/01/2013

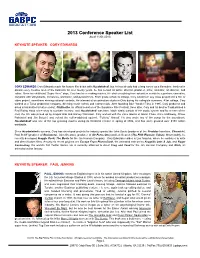

2013 Conference Speaker List As of 11/01/2013 KEYNOTE SPEAKER: CORY EDWARDS CORY EDWARDS Cory Edwards made his feature film debut with Hoodwinked!, but he has already had a long career as a filmmaker. Involved in almost every creative area of the business for over twenty years, he has served as writer, director, producer, actor, animator, art director, and editor. Since his childhood “Super 8mm” days, Cory has been making movies. He shot everything from adventure serials to superhero comedies, complete with storyboards, miniatures, animation, and pyrotechnics. From grade school to college, Cory would turn any class project into a film or video project, sometimes winning national contests. He interned at an animation studio in Ohio during his collegiate summers. After college, Cory worked at a Tulsa production company, directing music videos and commercials. After founding Blue Yonder Films in 1995, Cory produced and acted in his brother’s feature debut, Chillicothe, an official selection of the Sundance Film Festival. Soon after, Cory and his brother Todd pitched a Red Riding Hood crime story to a private investor, and Hoodwinked! was born. Made totally outside of the studio system and for a tenth of the cost, the film was picked up by moguls Bob and Harvey Weinstein. Cory worked with the voice talents of Glenn Close, Anne Hathaway, Chazz Palminteri and Jim Belushi, and voiced the coffee-addicted squirrel, “Twitchy” himself. He also wrote two of the songs for the soundtrack. Hoodwinked! was one of the top grossing movies during its theatrical release in spring of 2006, and has since grossed over $150 million worldwide.