Michael Rakowitz: the Invisible Enemy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected]

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Matuschak, Jennie, "Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War" (2019). Honors Theses. 486. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/486 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments My first thanks is to my advisor, Mehmet Döşemeci. Without taking your class my freshman year, I probably would not have become a history major, which has changed my outlook on the world. Time will tell whether this is good or bad, but for now I am appreciative of your guidance. Also, thank you to my second advisor, Beeta Baghoolizadeh, who dealt with draft after draft and provided my thesis with the critiques it needed to stand strongly on its own. Thank you to my friends for your support and loyalty over the past four years, which have pushed me to become the best version of myself. Most importantly, I value the distractions when I needed a break from hanging out with Saddam. Special shout-out to Andrew Raisner for painstakingly reading and editing everything I’ve written, starting from my proposal all the way to the final piece. -

4 Saddam As Hitler Anti-Americanism Has Multiple Dimensions. After Examin

Hoover Press : Berman/Europe DP0 HBERAE0400 rev1 page 83 4 Saddam as Hitler Anti-Americanism has multiple dimensions. After examin- ing the German data in chapter 1, in chapter 2 we explored several cultural and historical variants of anti-Americanism: first, an antimodern, predemocratic tradition; second, the legacy of communist ideology; and third, a contemporary, postdemocratic hostility to national sovereignty as such. Each version pushes anti-Americanism in a different direction. Chapter 3 looked at the tension between fantasy and reality in anti-Americanism, its ideological standing, and the role that anti-Americanism plays in the definition of an emerging identity for unified Europe. It is, however, obvious that current anti-Americanism has erupted in relation to the two Iraq wars. Although the various discourses of anti-Americanism refer to many issues, both political and cul- tural, it was clearly the confrontation between Washington and Baghdad that fueled the anger of the European street. Anti- Americans denounce the United States largely because it deposed Saddam Hussein. The first Iraq war was fought to end the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait. The second Iraq war was fought to end the Iraqi regime. Both wars, however, were fought in terms of a meta- phor: Saddam as Hitler. As this chapter will show, the terms of Hoover Press : Berman/Europe DP0 HBERAE0400 rev1 page 84 84 ANTI-AMERICANISM IN EUROPE the metaphor shifted over time. At first the analogy had the nar- row meaning of pointing out the unprovoked annexation of for- eign territory: just as Hitler had invaded Czechoslovakia, Saddam had swallowed Kuwait, both transgressions against internationally recognized borders. -

Architectural Identity Shaped by the Political System, Kurdistan Region

l Eng tura ine c er Othman, J Archit Eng Tech 2018, 7:1 ite in h g c r T e DOI: 10.4172/2168-9717.1000216 A c f h o n l Journal of Architectural o a l n o r g u y o J ISSN: 2168-9717 Engineering Technology Review Article Open Access Architectural Identity Shaped by the Political System, Kurdistan Region Since 1991 as a Case Study Halima A Othman* Engineering Department, University of Zakho, Duhok, Kurdistan region, Iraq Abstract “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us” Winston Churchill 1943. The ruling Elites utilize meaning in architectural forms to exercise their political power to unite and or manipulate people, here architectural signification plays a major role in the nationhood in creating and reaffirming the cultural identity for societies. Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural region wherein the Kurdish people form a prominent majority population, and Kurdish culture, languages, and national identity have historically been based. Following the discovery and exploitation of oil, paralleled with investment law in 2004, Kurdistan witnessed a bulk boom in the construction industry. Kurdistan region became architecture playground. Most of the pilot projects were prepared behind boarders by various international architectural styles, diminishing the regions local identity. One of the areas that suffered from the previous control system is neglecting and deconstructing of architectural identity. The paper is based on case study and observations. An inductive method will be used to analyze pilot projects in Kurdistan and how they reflect the political system’s desires instead of the culture and identity of the region. -

Triumph (Re-)Imagined: Saddam's Monument to Victory

International Journal of the Classical Tradition https://doi.org/10.1007/s12138-018-0495-5 ARTICLE Triumph (re-)Imagined: Saddam’s Monument to Victory Annelies Van de Ven1 © Springer Nature B.V. 2018 Introduction National narratives are not rootless; they are located in time as well as space.1 They are also not neutral, and each one carries within it a specific interpretation of the past, its literary and material remains, that is often focused on a particular territorial entity or cultural group. These interpretations form the basis for a national myth and they are incorporated into state ideologies to create a common national identity. The governing bodies of national and cultural groups can reform these historical sites, figures and events as tools to support a desired sense of identity. Through assessing how official interpretations of history are displayed in the public sphere through speeches, monuments or museum displays, we can begin to recreate these narratives and their processes of formation and revision. In this paper, I focus on the narrative of Saddam Hussein’s Victory Arch in Baghdad (Figure 1). The colossal structure was one of the many monuments erected by Saddam’s government in order to immortalize a new vision for the Iraqi nation. This vision did not only address Iraqi expectations for the nation’s future, but it reformulated their narratives of the past, creating a world in which the nation’s well- being depended on the continued supremacy of the Ba’th party and its leader. The Victory Arch was a particularly poignant symbol of this narrative and had pride of place within the government’s architectural repertoire. -

Walk to Jerusalem 2021 Week 6

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 6 We had another great week this week. We had 47participants and walked 1221.5 miles! The map below shows our progress through the end of week six (purple line). After an enjoyable time at Ur we headed for Baghdad, the capital of Iraq. Baghdad one of the largest cities in the Arab world, and compared to its large population it has a small area at just 260 square miles. Located along the Tigris, near the ruins of the Akkadian city of Babylon. If you recall the first reading on Sunday 3/14 (2 Chronicles 36:14-16,19-23), God led his people to the King of the Chaldeans (now Iraq) who invaded Jerusalem and destroyed much of Jerusalem, carrying off the survivors to Babylon where they became servants. And the people of Jerusalem stayed there until the king of Persia (Iran), Cyrus the Great helped rebuild Jerusalem. Panoramic view of the Tigris as it flows through Baghdad. Baghdad was founded in the 8th century and became the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate. Within a short time, Baghdad evolved into a significant cultural, commercial, and intellectual center of the Muslim world. Because there were several key academic institutions, including the House of Wisdom, as well as hosting a multiethnic and multireligious environment, garnered the city a worldwide reputation as the "Center of Learning". Baghdad was the largest city in the world for much of the Islamic Golden Age, peaking at a population of more than a million. The city was largely destroyed at the hands of the Mongol Empire in 1258, resulting in a decline that would linger through many centuries due to frequent plagues and multiple successive empires. -

Privatecirculation174-187

Pages 174–187 January-February 2010 Private Circulation The Monthly PDF Bulletin THE REVENGE OF TASTE Thus Godolphin received a nose bridge of ivory, a cheekbone of silver and a paraffin and celluloid chin … The reconstruction had been perfect … He talked like a man under death sentence. “Perhaps I can pawn my cheekbone. It’s worth a fortune. Before they melted it down it was one of a set of pastoral figurines, eighteenth century— nymphs, shepherdesses—looted from a château the Hun was using for a CP; Lord knows where they’re originally from—” —Thomas Pynchon, V. I. he Victory Arch (aka the Hands of TVictory, the Crossed Swords, or the Swords of Qadisiyya), a giant monument in Baghdad consisting of two pairs of hands crossing swords, was commissioned in 1985 to commemorate Iraq’s pre-emptive victory of the Iraq–Iran War, which ended in 1988. Each steel sword was made from the weapons of fallen Iraqi soldiers, and weighs about 24 tons—they are meant to represent the swords of Sa’ad ibn-abi Waqas, the com- mander of the Arab-Muslim army that de- feated the Persians in the battle of Qadisi- yya in AD 637. The hands were modeled after plaster casts of Saddam Hussein’s own hands. (While the swords were cast in Iraq, the bronze hands were cast in Britain by the Morris Singer Foundry.) Spilling out from the bottom of the monument are the helmets of Iranian soldiers, many of which are 174 January-February 2010 PrivateCirculation.com 175 January-February 2010 PrivateCirculation.com 176 January-February 2010 dented or have holes in them, presumably least one of the four bronze hands had been The finished sculpture was shipped to Fort from bullets and shrapnel. -

Iran's Declining Influence in Iraq

Babak Rahimi Iran’s Declining Influence in Iraq ‘‘Three Whom God Should Not Have Created: Persians, Jews, and Flies,’’ was the provocative title of a pamphlet published in 1940 by Saddam Hussein’s uncle, Khairallah Talfah.1 Saddam himself incorporated such anti-Iranian sentiment into Ba‘athist state ideology after his rise to power in 1979 and into the bloody 1980—1988 Iran—Iraq war. Such hostility is still visible today under the Victory Arch, popularly known as the Crossed Swords, in central Baghdad where thousands of the helmets of Iranian soldiers are held in nets, with some half buried in the ground. Before 2003, every year Saddam and his soldiers would proudly march over the helmets, as the symbol of Iraq’s triumph over Persia. Now, however, such historical enmity appears a distant past. With the 2003 collapse of the Ba‘athist regime and the ascendency of Iraq’s Shi‘a majority in the country’s economic and political life, Iran and Iraq now seem at their most amicable since the 1955 Baghdad Pact when they signed treaties for greater cooperation and aligned against separatist movements as well as the Soviet threat. With the rapid expansion of economic ties and movement of goods, products, and people, relations between the two countries have improved considerably across the border where many bloody battles were fought in the 1980s. Iraqi politicians now regularly visit Tehran while Iranian officials, in turn, travel to Baghdad to meet their counterparts. Along with enhanced elite relations, the growth of cultural and religious interaction also speaks of a revival of historical relations between the two countries that can trace close ties to the Safavid era, when Baghdad and southern Iraq were, periodically between 1508 and 1638, governed by Shi‘a Iranian kings. -

The Worst Condition Is to Pass Under a Sword Which Is Not One's Own Is Curated by Ann Coxon and Rachel Taylor

in our previous episodes... CANADIAN AERODYNAMICIST GERALD BULL TAKES HIS CHILDHOOD DREAM OF BUILDING THE WORLD’S BIGGEST GUN TO BARBADOS, WHERE THE US AND CANADIAN GOVERNMENTS COMMISSION A SUPERGUN CAPABLE OF FIRING PAYLOADS INTO SPACE... WHILE IN IRAQ, A CIA-SPONSORED BA’ATHIST COUP CULMINATES IN THE EXECUTION OF GENERAL ABDUL KARIM QASIM. AFTER HIS DEATH, RUMORS CIRCULATE IN BAGHDAD THAT HIS FACE CAN BE SEEN ON THE MOON. ONLY FIVE YEARS EARLIER, IN THE AGENCY’S FIRST ATTEMPT TO DEPOSE THE IRAQI PRESIDENT, THE HIRED GUNMAN—SADDAM HUSSEIN—LOST HIS NERVE AND MISFIRED. DR. BULL’S EXPERIMENTS IN THE CARIBBEAN ARE MOTHBALLED IN 1972, BUT HIS FINDINGS RESURFACE A DECADE LATER WHEN PRESIDENT REAGAN DEVELOPS THE STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE AGAINST SOVIET MISSILE ATTACK, AKA STAR WARS. ON JULY 22, 2003, THE US ARMY DESCENDED ON A HOUSE IN MOSUL WHERE SADDAM HUSSEIN’S SONS UDAY AND QUSAY WERE BELIEVED TO BE HIDING. AT LARGE SINCE THE BEGINNING OF THE AMERICAN-LED INVASION THAT MARCH, THE BROTHERS WOULD BE DEAD BY THE END OF THE ENSUING FOUR-HOUR GUNFIGHT. IN HIS LAST MOMENTS, DID UDAY THINK TO COMPARE HIS SITUATION WITH THE OPENING SCENE OF ONE OF HIS FAVORITE FILMS? DID HE BELIEVE HE WAS FIGHTING WITH THE GOOD GUYS, OR AGAINST THEM? UDAY HAD HAD A STORIED PAST IN HIS FATHER’S IRAQ. HE’D GRADUATED TOP OF HIS CLASS AT BAGHDAD UNIVERSITY IN 1984, ONLY TO BE BANISHED TO SWITZERLAND FOUR YEARS LATER. HE’D KILLED HIS FATHER’S PERSONAL VALET AND FOOD TASTER—KAMAL GEGEO HAD INTRODUCED SADDAM TO A YOUNGER WOMAN, AN INSULT TO UDAY’S MOTHER. -

The Reciprocal Connection Between Ba'athist War Monuments and Iraqi

The Reciprocal Connection Between Ba’athist War Monuments and Iraqi Collective Identity dr. J.A. Naeff Teba Al-Samarai S1440594 Cultures of Dissent Resistance, Revolt 9,703 words and Revolution in the Middle East 13-01-2017 This page is intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Iraq’s Historical and Political Context of the Monuments During 5 the Iran-Iraq War 1.1. The Ba’athist Regime and the Iran-Iraq War 5 1.2. Iraq’s Collective Identity during the Iran-Iraq War 7 1.3. Introducing the Monuments 9 Martyr’s Memorial 9 Victory Arch Monument 11 2. Triumphalism 14 2.1.Saddam’s Qadisiyyah: The Triumphalist War Narrative of the 14 Ba’athist Regime The First and Second Battle of Qadisiyyah 15 Religious rhetoric 15 Ethnic rhetoric 16 Celebrations 17 Saddam: Exceptional or Traditional? 17 2.2.Triumphalism and the Monuments 18 Triumphalism and the Victory Arch Monument 18 Triumphalism and the Martyr’s Memorial 20 3. Mourning 23 3.1. Individual, Collective and Symbolic Mourning: Construction 23 and Monuments 3.2. Mourning and the Monuments 26 Mourning and the Martyr’s Memorial 26 Mourning and the Victory Arch Monument 28 Conclusion 30 Works cited 32 Appendix 36 Introduction With their relative recent emergence in theoretical approaches, the neologisms ‘collective memory’ and ‘collective identity’ have proven to be key concepts, employed through various fields of literature. However, Gillis noted the inconsistent use of both concepts due to their subjective nature and defined both notions by building on Anderson’s highly influential work ofImagined Communities, who argues that a nation is socially constructed and as an imagined political community (3-4). -

How to Deal with Difficult Heritage Sites from Nazi Germany to the Baathist Regime in Iraq

Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies How to deal with difficult heritage sites from Nazi Germany to the Baathist Regime in Iraq Research Department Al-Bayan Center Studies Series About Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies is an independent, nonprofit think tank based in Baghdad, Iraq. Its primary mission is to offer an authentic perspective on public and foreign policy issues related to Iraq and the region. Al-Bayan Center pursues its vision by conducting independent analysis, as well as proposing workable solutions for complex issues that concern policymakers and academics. Copyright © 2019 www.bayancenter.org 2 How to deal with difficult heritage sites from Nazi Germany to the Baathist Regime in Iraq How to deal with difficult heritage sites from Nazi Germany to the Baathist Regime in Iraq Research Department Abstract Monuments and buildings are a physical connection to our past. They represent our history and through their public presence tell a story, which over time enshrines itself into our identity and our being. As such, statues, monuments and heritage sites have long been used as political tools to represent leaders and their ideology. Particularly during the times of authoritarian rules, the building of representative structures becomes a tool to create loyalty and bind the population to its head of state. The following report pursues the question of how to deal with physical heritage remaining from authoritarian regimes upon their demise. On the example of the Baathist regime under Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the report will analyse past and current happenings in the country with regards to heritage maintenance, reconfiguration, removal and destruction and will propose a best way forward. -

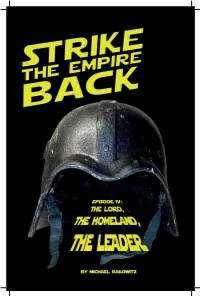

Iraqi Food for Thought: Michael Rakowitz's Backstroke of the West

Iraqi food for thought: Michael Rakowitz's Backstroke of the West As his first career retrospective in the US opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Rakowitz tells Nick Leech how he uses art to overcome prejudice Nick Leech September 15, 2017 In the first week of February, 2005, an Iraq-based terrorist group calling itself the Mujahideen Brigades released an image of a captured US soldier, who they named as John Adams. Held at gunpoint in front of the kind of black flag now inextricably associated with ISIL, the group threatened to kill the African-American unless Iraqis held in US-run prisons were freed within 72 hours. Responding to the news, the US military scoured the country for news of missing personnel – there was none – and within hours it became clear that the Adams case was not quite what it seemed. The suspicion was confirmed when an American toy manufacturer, Dragon Models USA, released a statement that noted the facial similarity between Adams and one of their replica servicemen, “Cody”, an action toy designed to resemble a member of the US special forces. The story blew over almost as quickly as it had come to light, one of the many stranger- than-fiction episodes to emerge from the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, such as the case of Saddam Hussein’s son Uday, leader of the Fedayeen Saddam paramilitary unit and an avid Star Wars fan, who designed the helmet worn by his troops to resemble Darth Vader’s, or the fact that, on the eve of the first Gulf War, Saddam’s troops marched through the triumphal Hands of Victory arch in Baghdad to the Star Wars theme tune. -

Building War Through Militarization, Memorialization, and Recreationalization of the Urban Middle East

All That Is Holy Is Profaned: Building War through Militarization, Memorialization, and Recreationalization of the Urban Middle East By Ayda Taghikhani Melika A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Co-chair Professor Andy Shanken, Co-chair Professor Galen Cranz Professor Cihan Tugal Fall 2018 Copyright © 2018 Ayda Taghikhani Melika Abstract All That Is Holy Is Profaned: Building War Through Militarization, Memorialization, and Recreationalization of the Urban Middle East by Ayda Taghikhani Melika Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professors Nezar AlSayyad and Andy Shanken, Co-chairs The greatest enemy of humanity is not war; it is the illusion of humanism and peacemaking. The convergence of militarization, memorialization, and recreationalization is a widespread modern phenomenon observed in spatial and architectural manifestations worldwide. For example, memorial parks have often been dedicated to the memory of wars while simultaneously designed for recreational activities. In this dissertation, I examine how these sites, which are often erected under the legitimizing banner of humanitarian or sacred values, are designed to have political socialization and militarization effects on the users. The neoliberal militarization of spaces of daily life, collective memory and recreations shape the political landscape of our world threatening societies with a slow but steady normalization of war and the spread of a deadly culture of global violence. Implementation of extensive spatial militarization, memorialization, and recreationalization is aiding the spread of neoliberalism in the formation of new Middle Eastern cities.