Tuning and Temperament in Southern Germany to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Swinging Spring: Regular and Chaotic Motion

References The Swinging Spring: Regular and Chaotic Motion Leah Ganis May 30th, 2013 Leah Ganis The Swinging Spring: Regular and Chaotic Motion References Outline of Talk I Introduction to Problem I The Basics: Hamiltonian, Equations of Motion, Fixed Points, Stability I Linear Modes I The Progressing Ellipse and Other Regular Motions I Chaotic Motion I References Leah Ganis The Swinging Spring: Regular and Chaotic Motion References Introduction The swinging spring, or elastic pendulum, is a simple mechanical system in which many different types of motion can occur. The system is comprised of a heavy mass, attached to an essentially massless spring which does not deform. The system moves under the force of gravity and in accordance with Hooke's Law. z y r φ x k m Leah Ganis The Swinging Spring: Regular and Chaotic Motion References The Basics We can write down the equations of motion by finding the Lagrangian of the system and using the Euler-Lagrange equations. The Lagrangian, L is given by L = T − V where T is the kinetic energy of the system and V is the potential energy. Leah Ganis The Swinging Spring: Regular and Chaotic Motion References The Basics In Cartesian coordinates, the kinetic energy is given by the following: 1 T = m(_x2 +y _ 2 +z _2) 2 and the potential is given by the sum of gravitational potential and the spring potential: 1 V = mgz + k(r − l )2 2 0 where m is the mass, g is the gravitational constant, k the spring constant, r the stretched length of the spring (px2 + y 2 + z2), and l0 the unstretched length of the spring. -

The Organ Ricercars of Hans Leo Hassler and Christian Erbach

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame 3. When a map, dravdng or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

Dynamics of the Elastic Pendulum Qisong Xiao; Shenghao Xia ; Corey Zammit; Nirantha Balagopal; Zijun Li Agenda

Dynamics of the Elastic Pendulum Qisong Xiao; Shenghao Xia ; Corey Zammit; Nirantha Balagopal; Zijun Li Agenda • Introduction to the elastic pendulum problem • Derivations of the equations of motion • Real-life examples of an elastic pendulum • Trivial cases & equilibrium states • MATLAB models The Elastic Problem (Simple Harmonic Motion) 푑2푥 푑2푥 푘 • 퐹 = 푚 = −푘푥 = − 푥 푛푒푡 푑푡2 푑푡2 푚 • Solve this differential equation to find 푥 푡 = 푐1 cos 휔푡 + 푐2 sin 휔푡 = 퐴푐표푠(휔푡 − 휑) • With velocity and acceleration 푣 푡 = −퐴휔 sin 휔푡 + 휑 푎 푡 = −퐴휔2cos(휔푡 + 휑) • Total energy of the system 퐸 = 퐾 푡 + 푈 푡 1 1 1 = 푚푣푡2 + 푘푥2 = 푘퐴2 2 2 2 The Pendulum Problem (with some assumptions) • With position vector of point mass 푥 = 푙 푠푖푛휃푖 − 푐표푠휃푗 , define 푟 such that 푥 = 푙푟 and 휃 = 푐표푠휃푖 + 푠푖푛휃푗 • Find the first and second derivatives of the position vector: 푑푥 푑휃 = 푙 휃 푑푡 푑푡 2 푑2푥 푑2휃 푑휃 = 푙 휃 − 푙 푟 푑푡2 푑푡2 푑푡 • From Newton’s Law, (neglecting frictional force) 푑2푥 푚 = 퐹 + 퐹 푑푡2 푔 푡 The Pendulum Problem (with some assumptions) Defining force of gravity as 퐹푔 = −푚푔푗 = 푚푔푐표푠휃푟 − 푚푔푠푖푛휃휃 and tension of the string as 퐹푡 = −푇푟 : 2 푑휃 −푚푙 = 푚푔푐표푠휃 − 푇 푑푡 푑2휃 푚푙 = −푚푔푠푖푛휃 푑푡2 Define 휔0 = 푔/푙 to find the solution: 푑2휃 푔 = − 푠푖푛휃 = −휔2푠푖푛휃 푑푡2 푙 0 Derivation of Equations of Motion • m = pendulum mass • mspring = spring mass • l = unstreatched spring length • k = spring constant • g = acceleration due to gravity • Ft = pre-tension of spring 푚푔−퐹 • r = static spring stretch, 푟 = 푡 s 푠 푘 • rd = dynamic spring stretch • r = total spring stretch 푟푠 + 푟푑 Derivation of Equations of Motion -

Download the Just Intonation Primer

THE JUST INTONATION PPRIRIMMEERR An introduction to the theory and practice of Just Intonation by David B. Doty Uncommon Practice — a CD of original music in Just Intonation by David B. Doty This CD contains seven compositions in Just Intonation in diverse styles — ranging from short “fractured pop tunes” to extended orchestral movements — realized by means of MIDI technology. My principal objectives in creating this music were twofold: to explore some of the novel possibilities offered by Just Intonation and to make emotionally and intellectually satisfying music. I believe I have achieved both of these goals to a significant degree. ——David B. Doty The selections on this CD process—about synthesis, decisions. This is definitely detected in certain struc- were composed between sampling, and MIDI, about not experimental music, in tures and styles of elabora- approximately 1984 and Just Intonation, and about the Cageian sense—I am tion. More prominent are 1995 and recorded in 1998. what compositional styles more interested in result styles of polyphony from the All of them use some form and techniques are suited (aesthetic response) than Western European Middle of Just Intonation. This to various just tunings. process. Ages and Renaissance, method of tuning is com- Taken collectively, there It is tonal music (with a garage rock from the 1960s, mendable for its inherent is no conventional name lowercase t), music in which Balkan instrumental dance beauty, its variety, and its for the music that resulted hierarchic relations of tones music, the ancient Japanese long history (it is as old from this process, other are important and in which court music gagaku, Greek as civilization). -

The Sonata, Its Form and Meaning As Exemplified in the Piano Sonatas by Mozart

THE SONATA, ITS FORM AND MEANING AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIANO SONATAS BY MOZART. MOZART. Portrait drawn by Dora Stock when Mozart visited Dresden in 1789. Original now in the possession of the Bibliothek Peters. THE SONATA ITS FORM AND MEANING AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIANO SONATAS BY MOZART A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS BY F. HELENA MARKS WITH MCSICAL EXAMPLES LONDON WILLIAM REEVES, 83 CHARING CROSS ROAD, W.C.2. Publisher of Works on Music. BROUDE BROS. Music NEW YORK Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the Library of DR. ARTHUR PLETTNER AND ISA MCILWRAITH PLETTNER Crescent, London, S.W.16. Printed by The New Temple Press, Norbury PREFACE. undertaking the present work, the writer's intention originally was IN to offer to the student of musical form an analysis of the whole of Mozart's Pianoforte Sonatas, and to deal with the subject on lines some- what similar to those followed by Dr. Harding in his volume on Beet- hoven. A very little thought, however, convinced her that, though students would doubtless welcome such a book of reference, still, were the scope of the treatise thus limited, its sphere of usefulness would be somewhat circumscribed. " Mozart was gifted with an extraordinary and hitherto unsurpassed instinct for formal perfection, and his highest achievements lie not more in the tunes which have so captivated the world, than in the perfect sym- metry of his best works In his time these formal outlines were fresh enough to bear a great deal of use without losing their sweetness; arid Mozart used them with remarkable regularity."* The author quotes the above as an explanation of certain broad similarities of treatment which are to be found throughout Mozart's sonatas. -

MTO 20.2: Wild, Vicentino's 31-Tone Compositional Theory

Volume 20, Number 2, June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Genus, Species and Mode in Vicentino’s 31-tone Compositional Theory Jonathan Wild NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.wild.php KEYWORDS: Vicentino, enharmonicism, chromaticism, sixteenth century, tuning, genus, species, mode ABSTRACT: This article explores the pitch structures developed by Nicola Vicentino in his 1555 treatise L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica . I examine the rationale for his background gamut of 31 pitch classes, and document the relationships among his accounts of the genera, species, and modes, and between his and earlier accounts. Specially recorded and retuned audio examples illustrate some of the surviving enharmonic and chromatic musical passages. Received February 2014 Table of Contents Introduction [1] Tuning [4] The Archicembalo [8] Genus [10] Enharmonic division of the whole tone [13] Species [15] Mode [28] Composing in the genera [32] Conclusion [35] Introduction [1] In his treatise of 1555, L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (henceforth L’Antica musica ), the theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino describes a tuning system comprising thirty-one tones to the octave, and presents several excerpts from compositions intended to be sung in that tuning. (1) The rich compositional theory he develops in the treatise, in concert with the few surviving musical passages, offers a tantalizing glimpse of an alternative pathway for musical development, one whose radically augmented pitch materials make possible a vast range of novel melodic gestures and harmonic successions. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Comparison of Procedures for Determination of Acoustic Nonlinearity of Some Inhomogeneous Materials

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Dec 17, 2017 Comparison of procedures for determination of acoustic nonlinearity of some inhomogeneous materials Jensen, Leif Bjørnø Published in: Acoustical Society of America. Journal Link to article, DOI: 10.1121/1.2020879 Publication date: 1983 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Jensen, L. B. (1983). Comparison of procedures for determination of acoustic nonlinearity of some inhomogeneous materials. Acoustical Society of America. Journal, 74(S1), S27-S27. DOI: 10.1121/1.2020879 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. PROGRAM OF The 106thMeeting of the AcousticalSociety of America Town and CountryHotel © San Diego, California © 7-11 November1983 TUESDAY MORNING, 8 NOVEMBER 1983 SENATE/COMMITTEEROOMS, 8:30 A.M. TO 12:10P.M. Session A. Underwater Acoustics: Arctic Acoustics I William Mosely,Chairman Naval ResearchLaboratory, Washington, DC 20375 Chairman's Introductions8:30 Invited Papers 8:35 A1. -

Tutorial #5 Solutions

Name: Other group members: Tutorial #5 Solutions PHYS 1240: Sound and Music Friday, July 19, 2019 Instructions: Work in groups of 3 or 4 to answer the following questions. Write your solu- tions on this copy of the tutorial|each person should have their own copy, but make sure you agree on everything as a group. When you're finished, keep this copy of your tutorial for reference|no need to turn it in (grades are based on participation, not accuracy). 1. When telephones were first being developed by Bell Labs, they realized it would not be feasible to have them detect all frequencies over the human audible range (20 Hz - 20 kHz). Instead, they defined a frequency response so that the highest-pitched sounds telephones could receive is 3400 Hz and lowest-pitched sounds they could detect are at 340 Hz, which saved on costs considerably. a) Assume the temperature in air is 15◦C. How large are the biggest and smallest wavelengths of sound in air that telephones are able to receive? We can find the wavelength from the formula v = λf, but first we'll need the speed: v = 331 + (0:6 × 15◦C) = 340 m/s Now, we find the wavelengths for the two ends of the frequency range given: v 340 m/s λ = = = 0.1 m smallest f 3400 Hz v 340 m/s λ = = = 1 m largest f 340 Hz Therefore, perhaps surprisingly, telephones can pick up sound waves up to a meter long, but they won't detect waves as small as the ear receiver itself. -

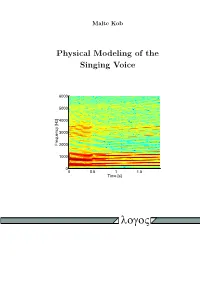

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models . -

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications Minseon Song May 17, 2014 Abstract Transformational theory is a modern branch of music theory developed by David Lewin. This theory focuses on the transformation of musical objects rather than the objects them- selves to find meaningful patterns in both tonal and atonal music. A generalized interval system is an integral part of transformational theory. It takes the concept of an interval, most commonly used with pitches, and through the application of group theory, generalizes beyond pitches. In this paper we examine generalized interval systems, beginning with the definition, then exploring the ways they can be transformed, and finally explaining com- monly used musical transformation techniques with ideas from group theory. We then apply the the tools given to both tonal and atonal music. A basic understanding of group theory and post tonal music theory will be useful in fully understanding this paper. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Crash Course in Music Theory 2 3 Introduction to the Generalized Interval System 8 4 Transforming GISs 11 5 Developmental Techniques in GIS 13 5.1 Transpositions . 14 5.2 Interval Preserving Functions . 16 5.3 Inversion Functions . 18 5.4 Interval Reversing Functions . 23 6 Rhythmic GIS 24 7 Application of GIS 28 7.1 Analysis of Atonal Music . 28 7.1.1 Luigi Dallapiccola: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera, No. 3 . 29 7.1.2 Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kreuzspiel, Part 1 . 34 7.2 Analysis of Tonal Music: Der Spiegel Duet . 38 8 Conclusion 41 A Just Intonation 44 1 1 Introduction David Lewin(1933 - 2003) is an American music theorist.