The Influence of International Schools on Egyptian Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Medical Doctors

Embassy of Switzerland in Egypt List of Medical Doctors/Therapists / ÄRZTELISTE NACH FACHGEBIET / Liste des médecins par spécialité Last update: 02/2020 (This list is being released with neither the endorsement nor the guarantee of the Embassy) Embassy’s medical doctor / Vertrauensarzt / Médecin de confiance Embassy’s medical doctor: Tel : +202 3338 2393 Address: Tel : +202 3761 1797 2, El-Fawakeh Street, Mohandessin, Dr. Abdel Meguid KASSEM near Moustafa Mahmoud Mosque -Giza. specialty: Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Infections Mobile : +20 100 176 8255 Hours: German, English, Arabic [email protected] Sunday - Wednesday [email protected] 17h30 – 20h00 Dr. Cherine KAHIL Tel: + 202 27 35 83 84 Home visit French, English , Arabic Mobile : +20 122 218 2279 [email protected] Dr. Sabine KLINKE Work location FDFA, Company Medical Officer Tel. : +41 58 481 4536 Freiburgstrasse 130, Bern, CH [email protected] Office no. A-2247 Medical Doctor (Internist) / ALLGEMEINMEDIZINER / Médecine générale (interniste) Dr. Sherif Doss Tel: +202 2358 3105 Address: English, Arabic Clinic Dr. Sherif DOSS Mobile : +20 122 210 3473 87, road 9 (Floor No. 5 ) Maadi [email protected] Clinic Hours Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday 13h00 - 15h00 Dr. Ramez Guindy Cairo Specialized Hospital Address: English, Arabic Heliopolis, 4 Abou Ebaid El Bakry St. Internist Doctor & Cardiology Mobile : +20 122 215 8305 Off Ghernata St; Roxy- Heliopolis Tel : +202 2450 9800 ext 234 Hours [email protected] Saturday – Monday – Wednesday : 11h00 – 14h00 Sunday – Tuesday – Thursday : 15h00 – 17h00 Italian Hospital & Ain Shams Address: Reservation number : 17, El Sarayat St., El Abbasia - Cairo - Egypt +20 122 022 6501 Hours Sunday – Tuesday – Thursday : 10h00 - 12h30 Dr. -

Cairo American College ▪ +20 2 2755 5411/12

Cairo American College www.cacegypt.org ▪ +20 2 2755 5411/12 High School Counselors Local address: Claudia Bean [email protected] 1 Midan Digla Stephanie Barker [email protected] Road 253 Cameron Simon [email protected] Maadi, Cairo Dear College Representatives, We are very excited about the opportunity to host you on our campus and look forward to welcoming you soon. Hopefully the information provided below will help you in planning your visit to Cairo. Meeting Time: All College Visits are held on the following days/times: Sunday through Thursday 10:30 – 11:00 with counselors and 11:05 – 11:55 with students (school is not in session on Friday’s as it is the first day of our weekend). The time with students is during their lunch break. We have several ways to announce college visits to students but do not require them to register to attend the session in advance…therefore, due to the nature of CAC (busy place) the number of students could vary from one to thirty. Travel Time: This will depend on your hotel location. Downtown- 45 – 60 minutes Heliopolis- 45 – 60 minutes Nasr City- 45 – 60 minutes Giza- 45 – 60 minutes Maadi- 5 – 15 minutes (recommendations on places to stay nearby are below) Please check with your Hotel for more exact travel time. Taxi: White Taxi: pick up on street The white taxis are your best option. Some may have me te r s . Make sure the meter reads about 5LE when you start out or ask the cost before you get in. The cost should be no more than 50LE from where ever you are coming. -

Meet Our New Mes Cairo Teachers

Contents Whole School Principal Foreword 3 American Section Student of the Month and 52 British Section MES All Stars Graduation Ceremony 4 Staff Professional Development 53 American Section Results 7 Primary Science Week 54 British Section Results 8 Foundation Stage One Induction Day 56 IBDP Results 10 Foundation Stage Two 57 UK Universities Update 11 Year One 58 British Section Scholarship Winner 12 Year Two 59 American Section Scholarship Winner 13 Year Three 60 IBDP Section Scholarship Winner 14 Year Four 61 IBDP News and CAS Residential 15 Year Five Concert 62 MEIBA and IBDP Jobalike Event 21 Year Six Leaver’s Day 63 WIRED and Going Google 22 Primary Sportsdesk 64 Digital Citizenship 24 Primary ASAs 67 American Section Science Update 26 Primary Pioneer Programme 68 Grade Seven and Eight Fagnoon Trip 28 Secondary Pioneer Programme 69 Grade Seven and Nine Back to School 29 Nights International Award News 70 HRCF and Grade Nine Escape Rooms 30 Secondary ASAs 71 Grade Ten Poetry Slam 31 MES Cairo Achievers 72 British Section Transition Day 32 Lara Majid’s New York Internship 73 British Section Maths Update 33 NHS/NJHS Induction Ceremony 74 Year Seven ToTAL News 35 Secondary Sportsdesk 75 Year Eight News 36 MES Cairo Welcomes New Teachers 82 Year Nine News 37 Halloween Happiness 90 Humanities News 39 MESConians – Where Are They Now? 91 Year Eight – Ahmed Zewail Day 40 Remembrance Day 92 Creative Arts News 41 MES Cairo Ladies Pharaonic Run and Sahl 93 Hasheesh Triathlon Evita Spoiler 47 MES Cairo New Births, Cairo Opera House 94 HRCF Middle School Madness 48 and Breast Cancer Awareness HRCF Motivated Mentors 49 MESMerised 95 Secondary House News 50 2 WHOLE SCHOOL PRINCIPAL FOREWORD pace and purpose of a term at our school school. -

International Acac College University and High School

INTERNATIONAL ACAC UPDATED: MARCH 31 2018 COLLEGE UNIVERSITY AND HIGH SCHOOL MEMBERS Group First Name Last Name Institution Region College anD University Members Jorge Garcia Abilene Christian University Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Shannon Paul ADelphi University Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Ashley Shaner ADelphi University Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Alexa Gaeta Agnes Scott College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Nazanin Tork Agnes Scott College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Emily-Davis Hamre Agnes Scott College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Katie Potapoff Alberta College of Art + Design Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Dmetri Berko Alberta College of Art + Design Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Elizabeth Morley Albion College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Cornell LeSane Allegheny College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Luiz Pereira Allegheny College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Gavin Hornbuckle American School of Brasilia South America College anD University Members Julie MerenDino American University Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Nadine Naffah American University of Beirut MiDDle East & North Africa College anD University Members Xiaofeng Wan Amherst College Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Arian Kotsi Anatolia College Europe College anD University Members Daniel Gerbatch Arizona State University Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Kathleen Dixon Arizona State University South America College anD University Members Kevin Chao Arizona State University Canada & U.S. College anD University Members Hilary Colvey Arts University Bournemouth Europe College anD University Members JarreD Miller Asbury University Canada & U.S. -

Myriam Ahmadi and Ilaria Borelli Winter Getaway Gifts Catering Festive Fashion

www.cairoeastmag.com December 2020 Issue No. 97 Free Community Magazine Powered by Cairo West Publications Serving Katameya, Maadi, Heliopolis and New Cairo Two Women Directors to Watch Myriam Ahmadi and Ilaria Borelli Winter Getaway Gifts Catering Festive Fashion TABLE OF CONTENTS December 2020 JAMILA AWAD & MYRIAM AHMADI TALK ABOUT VITILIGO IN LAZEM AEESH FASHION FeatuRES It’s Time to Party The Goat- Ilaria Borelli and Dominique Pinault Casa Cook – El Gouna BEAUTY Christmas Gift Guide Natural Scrubs for a Festive Glow Dahabiya Dreaming WELLBEING Vitiligo Tech and Wellbeing Tabibi: A Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body ENTERtaINMENT iRead Meet the Author Diwan: Recommendations for Holiday Reading TV: What’s new in December Art Scene Naomi Review Crave Coy Review OX Review Wellbeing La Gourmandise Takosan Review Schedules Review Bongoyo Review What’s New Moxie Review Noi Review Upcoming Events OUR TEAM Founder & Publisher Shorouk Abbas Editor-in-Chief Atef Abdelfattah Content Director Hilary Diack Copyediting Nahla Samaha General Manager Nihad Ezz El Din Amer Sales and Marketing Manager Nahed Hamy Assistant to General Manager Lobna Farag Assistant Marketing Manager Yomon Al-Mallah Digital Marketing Specialist Mariam Abd El Ghaffar Web & Social Media Ahmed Shahin Digital Content Aliaa El Sherbini Digital Content Creators Mariam Elhamy, Basem Mansour Graphic Designers Ahmed Salah, Essam Ibrahim Photography Mohamed Meteab Accountant Mohamed Mahmoud Distribution Ahmed Haidar, Mohamed El Saied, Mohamed Najah, Mohamed Shaker Mekkawy Printing IPH (International Printing House) Produced by Cairo West Publications Issued with registration from London No. 837545 Cairo Alex Desert Road - El Naggar Office Building 2 This magazine is created and owned by For advertising contact: Cairo West Advertising. -

MES62-Final.Pdf

Contents Whole School Principal Foreword 3 Barnum - Whole School Production 5 Creative Arts Exhibition 9 Oriental Weavers Rug Competition 12 Council of British International Schools (COBIS) Art Competition 13 Primary Art 14 IBDP Visual Arts Exhibition 16 Drama in the Secondary Section 18 Primary Music 19 Foundation Stage One 20 Foundation Stage Two 22 Year One 23 Year Two 24 Year Three 25 Year Four 26 Year Five 29 Year Six 30 Key Stage Two – Times Table Rockstars 31 Year Seven Maths 32 World Scholar’s Cup 33 MES Cairo Achievers 33 Year Seven – Sharm El Sheikh Trip 34 Year Eight – Fayoum Trip 36 Year/Grade Seven and Eight – Spanish Trip 38 English in the American Section 40 Humanities Update 42 Secondary Learning Development Department News 44 IBDP News 46 MES Cairo Seniors - Universities Update 48 Secondary House News 49 Pioneers Update 50 Secondary Sportsdesk 52 Primary Sportsdesk 56 Touch Rugby 58 Continuing Professional Development 59 MES Cairo Jeans Day 62 MESmerised 63 2 WHOLE SCHOOL PRINCIPAL’S FOREWORD It is already Term Three, and an acclaimed stage show, a contemporary novel, an another highly productive and impressionist painting; to find joy in the things in life that significant academic year evoke emotional engagement and awaken the senses. We draws to a close. My wish for want them to be interesting people who are successful in every MES Cairo student, their their careers, successful parents and successful contributors parents, and our teachers is that to society. We want them to have empathy for others and they can reflect on their journey to be respectful of perspectives which may differ from their since September and recognise own. -

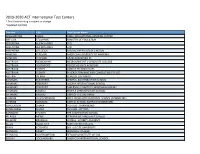

2019-2020 ACT International Test Centers * Test Center Listing Is Subject to Change

2019-2020 ACT International Test Centers * Test Center listing is subject to change. *Updated 2/24/20 Country City Test Center Name AFGHANISTAN KABUL KABUL EDUCATIONAL ADVISING CENTER ANTIGUA ST JOHNNS MINISTRY OF EDUCATION ARGENTINA BUENOS AIRES EXO ARGENTINA BUENOS AIRES EXO ARGENTINA LA LUCILA ASOCIACION ESCUELAS LINCOLN ARMENIA YEREVAN AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA ARMENIA YEREVAN GARIK ARAKELYAN PE AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE MELBOURNE INT'L GRADUATE COLLEGE AUSTRALIA SOUTHPORT FOREST HEIGHTS ACADEMY AUSTRALIA SYDNEY PARKUS TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA SYDNEY SYNERGY TRAINING AND CONSULTING PTY LTD AUSTRIA VIENNA SEMIZEN EDV GMBH BAHAMAS ELEUTHERA CENTRAL ELEUTHRA HIGH SCHOOL BAHAMAS FREEPORT LUCAYA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BAHAMAS FREEPORT TABERNACLE BAPTIST CHRISTIAN ACADEMY BAHAMAS NASSAU TEMPLE CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL BAHAMAS NASSAU UNIV OF THE BAHAMAS BAHRAIN AL MAZROWIAH RIFFA VIEWS INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL (CONNECME) BAHRAIN MANAMA CAPITAL SCHOOL BAHRAIN (CONNECME) BANGLADESH DHAKA TUV SUD - DHANMONDI BANGLADESH DHAKA TUV SUD - UTTARA BARBADOS ST JOHN THE CODRINGTON SCHOOL BELARUS MINSK STREAMLINE LANGUAGE SCHOOL BELGIUM BRUSSELS XCUELA - XCONIFY ACADEMY BELIZE BELIZE CITY SAINT JOHN'S COLLEGE BENIN COTONOU EPS - LA CITE UNIVERSITY BERMUDA PAGET BERMUDA COLLEGE BERMUDA SOUTHAMPTON BERMUDA INSTITUTE OF SDA BOLIVIA COCHABAMBA AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BOLIVIA LA PAZ AMERICAN COOPERATIVE SCHOOL BOLIVIA SANTA CRUZ SANTA CRUZ COOPERATIVE SCHOOL BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE CULTURA INGLESA BELO HORIZONTE BRAZIL BRASILIA CASA THOMAS JEFFERSON - FILIAL SUDOESTE -

Culture Shock Egypt

CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette Egypt Susan L Wilson cs! egypt.indd 1 1/27/11 12:21:08 PM CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette Egypt Susan L Wilson CS! Egypt.indb i 3/14/11 10:48 AM This 4th edition published in 2011 by: Marshall Cavendish Corporation 99 White Plains Road Tarrytown, NY 10591-9001 www.marshallcavendish.us First published in 1998 by Times Editions; 2nd edition published in 2001; 3rd edition published in 2006 by Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited. Copyright © 2006, 2011 Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited, 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196. Tel: (65) 6213 9300, fax: (65) 6285 4871. E-mail: [email protected] The publisher makes no representation or warranties with respect to the contents of this book, and specifi cally disclaims any implied warranties or merchantability or fi tness for any particular purpose, and shall in no event be liable for any loss of profi t or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Other Marshall Cavendish Offi ces: Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited. 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196 Marshall Cavendish International. PO Box 65829, London EC1P 1NY, UK Marshall Cavendish International (Thailand) Co Ltd. -

Edition No. 60

Contents Whole School Principal Foreword 3 Foundation Stage One 56 Graduation Ceremony 4 Foundation Stage Two 57 Pink Day - Breast Cancer Awareness Month 6 Year One 58 MESConian News 8 Year Two 59 British Section Results 10 Year Three Concert - Secrets of the Sands 60 IBDP Results 11 Year Four 61 American Section Results 12 Year Five 62 Senior Student Leaders 13 Year Six Leavers’ Day 63 IBDP News 18 Year Six Production 64 UK Universities Update 21 Primary School Council 65 Secondary School Council 22 MES Cairo Welcomes New Teachers 66 Grade Seven and Eight Field Trips 22 Staff Professional Development 77 Year Six to Year Seven Transition Day 24 Secondary Pioneers 79 Year Seven News 25 Primary Pioneers 81 Secondary Maths Focus 29 Primary ASA Programme 82 Year Eight Industry Day 30 Secondary ASA Programme 83 Secondary English Focus 31 International Award 84 Grade Seven to Nine Back to School Nights 34 NHS/NJHS Induction Ceremony 85 Expressive Arts 35 Secondary House News 86 E-Safety Workshop 43 IBDP CAS Trip 88 MES Cairo Achievers 44 Learning Development/Gifted and Talented 91 Barnum Spoiler 45 MESConian News – Where are the now? 93 Peripatetic Music 46 Halloween Spooktacular 94 Secondary Sportsdesk 47 Remembrance Day 95 Primary Sportsdesk 53 New Births 95 2 WHOLE SCHOOL PRINCIPAL FOREWORD Make Every Day Matter! That has been my mantra since school began this academic year; students and teachers at MES Cairo hear me say it often. The adults amongst us realise that life is short; the children in our care take some convincing. -

Office Profile

Office Profile 1 National Defense Buildings, Flat No. 52, El Koba, Cairo, Egypt Tel. +20 2 225 64 302, +20 100 565 495 [email protected] www.altakhteet.com Goal, Mission, and Vision Our Goal is to achieve client's objectives through utilizing their resources, and thus providing them with a reliable, safe and economic state-of-the-art design. To satisfy our clients completely is our main goal. Our Mission is to help the development of the real estate and infrastructure sectors in Egypt and the Middle East region by providing the highest standards and solutions in the fields of our experience. Our Vision is to establish a track record of success in leading a world-class Engineering Consultation. Build a coherent business services to deliver highly successful Structures' Solution using proper analysis/design approaches and through the use of the latest technologies. 1 INTRODUCTION Dar Al Takhteet is one of the competitive engineering offices fully geared up to take up the growth challenges in the Middle East region. With a team of experienced and talented engineers, Dar Al Takhteet is capable of serving their demanding clients from building, infrastructures and other core industrial sectors. The company members are all highly experienced, registered professionals with many years of practical exposure in their own fields of specialization both in Egypt and the Middle East. Dar Al Takhteet's prime goal is to invest in both human and material resources in Engineering Services so as to establish a base for human development and material gains by providing expert engineering services. Dar Al Takhteet has a good experience in the design of mega projects including building projects, over and underground metros, infrastructure, roads, traffic, and massive industrial units. -

Location School Website

OVERSEAS SCHOOLS LOCATION SCHOOL WEBSITE ARGENTINA Buenos Aires Lincoln, The American Int'l Schl of Buenos Aires http://www.lincoln.edu.ar/ ARUBA Oranjestad International School of Aruba http://www.isaruba.com/ AUSTRIA Vienna American International School http://www.ais.at/ BAHRAIN Isa Town Bahrain Bayan School http://www.bayanschool.edu.bh/ Riffa Naseem International School http://www.nisbah.com/ Sanad Al Hekma International Model School http://www.alhekma.com/alhekma/bahrain/ BANGLADESH Dhaka American International School/Dhaka http://www.aisdhaka.org/ BOLIVIA Cochabama Cochabama Cooperative School http://www.ccs.edu.bo/ La Paz American Cooperative School http://www.acslp.org/ Santa Cruz Santa Cruz Cooperative School http://web.sccs.edu.bo/ BRAZIL Belo Horizonte American School of Belo Horizonte http://www.eabh.com.br/en/ Brasilia American School of Brasilia http://www.eabdf.br/ Sao Paulo Chapel School - Escola Maria Imaculada http://www.chapelschool.com/ BURKINA FASO Ouagadougou International School of Ouagadougou http://iso.bf/ CAMEROON Yaounde American School of Yaounde http://www.asoy.org/ CHILE Santiago The International School Nido de Aguilas http://www.nido.cl/ CHINA Hong Kong International Christian School http://www.ics.edu.hk/ Tai Tam, Hong Kong, PRC Hong Kong International School http://www.hkis.edu.hk/ Shanghai Shanghai Changning International School https://www.scis-his.org/ Shanghai Concordia International School Shanghai http://www.concordiashanghai.org/ Kowloon, Hong Kong, PRC Yew Chung Education Foundation http://www.ycef.com/ OVERSEAS SCHOOLS LOCATION SCHOOL WEBSITE Shanghai, PRC Shangai American School http://www.saschina.org/ Guangzhou American International School of Guangzhou http://www.aisgz.org/ Xiamen Xiamen International School http://www.xischina.com/ COLOMBIA Barranquilla Karl C. -

THE BOOK of OUR LIVES Contents FORWARD

THE BOOK OF OUR LIVES Schutz American School Alexandria, Egypt 2nd Printing, 1997 Scanned and Formatted, Ed Nicholas, 2015 1 | Page FORWARD In the early years of The American Mission in Egypt, which was the official title of the United Presbyterian Church of North America doing mission work in Egypt, the education of the children of the missionaries became a matter of concern. Obviously, there were no schools in the country in those early years except for the Islamic schools for teaching the Koran. Therefore, in most cases the education of these foreign children fell on the mother of each family. There were reports that at times, however, when there were several families living in the same town, one mother took the responsibility for all the children. It should not be too hard to imagine such "schools" - slates and chalk for writing and arithmetic, the Bible for reading and possibly the McGuffy Readers for somewhat more "secular" studies. And later "Calvert" became a familiar name to those using the international postal service. There have been unwritten reports that a basement room in the Assiut mission hospital complex was used for a group of children in the early 1900's. However, by the 1920's it became apparent that there was a pressing need for a "school with a full time teacher to work with the numbers of children that were filling the mission family ranks. And so the story here begins with Mrs. Bernice Warne Hutton’s recollections of her participating in the establishing and then becoming one of the first teachers in what now is known as Schutz American School, Alexandria, Egypt.