Racing for Equality in Women's Competitive International Rowing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 ANNUAL REPORT RCA PURPOSE INSPIRE GROWTH and EXCELLENCE in Canada Through the Sport of Rowing

2018 ANNUAL REPORT RCA PURPOSE INSPIRE GROWTH AND EXCELLENCE in Canada through the sport of rowing. RCA VISION TABLE OF CONTENTS CANADA IS A LEADING 4 INTRODUCTION ROWING NATION 6 TREASURER’S REPORT To be a leader and an exemplar of best practice in sport development as well as sustainable success on 8 2018 ACTIVITY the international stage. To be seen as a nation that is 10 2018 RESULTS pushing boundaries and challenging the status quo as we seek to grow and get better everyday. 20 2018 MEMBERSHIP DEMOGRAPHICS & NATIONAL ACTIVITY 30 IN RECOGNITION 32 BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 34 APPENDIX - AUDITOR’S REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 35 > INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 36 > FINANCIALS 46 THANK YOU INTRODUCTION PRESIDENT AND CEO REPORT This has been a year of change and has captured a more accurate representation of the Hall of Fame continues to grow in significance, This year we saw more schools enjoying a successful a year of creating a foundation for participants of rowing in Canada. All Canadian and we look forward to announcing the class of 2019 Canadian Secondary Schools Rowing Association rowers pay a low base fee to register for membership to join those from 2018 inducted in January at the Regatta. The 136th Royal Canadian Henley future growth. We are committed and then a seat fee for each event they enter at a Conference last year. Regatta continues to set the benchmark for club to shifting the organization to more sanctioned event. This ‘pay as you row’ approach regattas across the World. The National Rowing open processes and input from assigns the cost to those who participate more in the It is hard to reflect on the last year without recognizing Championships significantly raised the bar on what can be achieved through the application of modern community as we make decisions sport. -

Press Release

Conseil International de International Council of l'Arbitrage en matière de sport Arbitration for Sport CIAS / TAS ICAS / CAS MEDIA RELEASE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT (ICAS) JOHN COATES RE-ELECTED AS ICAS PRESIDENT Lausanne, 22 May 2015 – On the occasion of its 43rd meeting, held in Lausanne (Switzerland), the International Council of Arbitration for Sport (ICAS) elected Mr John Coates (Australia) as President of ICAS for the period 2015-2018. Mr Coates has been a member of ICAS since the creation of the Council in 1994. He became the 3rd ICAS President in 2010, succeeding Judge Kéba Mbaye (Senegal, 1994-2007), founder and first President of ICAS, and Mr Mino Auletta (Italy, 2007-2010). Mr Coates is a lawyer from Sydney. He is President of the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and Vice-President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). At the same meeting, the ICAS also elected its two Vice-Presidents: Mr Michael Lenard (United States) and Mrs Tjasa Andrée-Prosenc (Slovenia). Mr Lenard, lawyer, is an Olympian in handball (1984), former Vice-President of the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) and former Vice-Chairman of the USOC Athlete Commission. Mrs Andrée-Prosenc, lawyer, was a national champion in figure and roller skating; she is a Council member of the International Skating Union (ISU), an ISU judge, referee and technical delegate at the Olympic Games and Executive Board Member of the NOC of Slovenia. The presidents of the CAS arbitration divisions have also been elected: Ordinary Arbitration Division: President: Mr Nabil Elaraby (Egypt); Mr Elaraby is a former Judge of the International Court of Justice in The Hague and former Foreign Minister of Egypt. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release Honours and Awards Secretariat May 17, 2012 Province of British Columbia 14 TO RECEIVE 2012 ORDER OF BRITISH COLUMBIA VICTORIA – Fourteen British Columbians who have contributed to the province in extraordinary ways will be awarded the Order of British Columbia, Lieutenant-Governor Steven Point, and Chancellor of the Order, announced today. “As our Province‟s highest honour, the Order of British Columbia is our way of acknowledging the outstanding achievements of our citizens. The recipients are an inspiration to all British Columbians,” Point said. “The Order of British Columbia recognizes the remarkable accomplishments achieved by extraordinary British Columbians,” said Premier Christy Clark. “This year‟s recipients have made exceptional contributions to their communities and to the province. On behalf of all British Columbians, I‟d like to thank each recipient for everything they have done for the province.” This year‟s recipients are: David Barrett of Victoria - elected leader and one of modern British Columbia‟s architects. Sister Nancy Brown of Vancouver - advocate for homeless and vulnerable young people. The Right Honourable Kim Campbell, P.C., C.C., Q.C. formerly of Vancouver - elected leader, trailblazer for women. Dr. Peter L. Cooperberg of Vancouver - world leader in the medical use of ultrasound. Christopher Gaze of Vancouver- cultural leader and founder of the Bard on the Beach Shakespeare Festival. Rick Harry (Xwalacktun) of West Vancouver-– internationally renowned artist, teacher and link between First Nations and other British Columbians. Norman B. Keevil of Vancouver- mining industry pioneer, entrepreneur and philanthropist. Hassan Khosrowshahi of Vancouver- entrepreneur, builder and generous supporter of community organizations. -

IOC Annual Report 2018 Credibility, Sustainability, Youth

IOC Annual Report 2018 Credibility, Sustainability, Youth The IOC Annual Report is produced on a 100% recycled – and carbon balanced – paper stock, and printed at a carbon neutral printer. Cover image: Athletes from the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea marched together behind the Korean unification flag at the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018. The IOC Annual Report 2018 Credibility Sustainability Yo u t h CONTENTS Contents Letter from President Bach 004 The IOC in 2018 006 Leading the Olympic Movement 008 The Olympic Movement 010 The International Olympic Committee 012 The IOC: Funding the Olympic Movement 014 Olympic Agenda 2020 016 IOC Sessions in 2018 018 Olympic Solidarity 019 National Olympic Committees (NOCs) 020 International Federations (IFs) 022 OIympic Movement Partners 024 Broadcast 031 Sustainability 035 Governance and Ethics 038 Strengthening Our Commitment to Good Governance and Ethics 046 IOC Members 048 Celebrating the Olympic Games 054 Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 056 Olympic Agenda 2020/New Norm 062 Preparations for Future Games 063 Candidature Process for the Olympic Winter Games 2026 068 Youth Olympic Games 070 Sustainability and the Olympic Games 076 002 IOC ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CREDIBILITY, SUSTAINABILITY, YOUTH CREDIBILITY, SUSTAINABILITY, YOUTH IOC ANNUAL REPORT 2018 003 CONTENTS Supporting and Protecting Clean Athletes 078 Olympic Solidarity in 2018 080 Athletes’ Declaration 082 Athlete Programmes 083 Protecting Clean Athletes 088 Promoting Olympism -

Annual Report 2011

CANADIAN OLYMPIC COMMITTEE ANNUAL REPORT 2011 “From an athlete’s perspective, “Give Your Everything” means that whatever happens, I can live with the result because I knew I had done every single thing possible to be my best when it counted. These athletes are stars for the real hard work they put in and it’s grounded in some incredible substance. I think the athletes deserve it.” Canadian Olympic Team Chef de Mission, Mark Tewksbury 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the President of the COC 6 Message from the CEO and Secretary General of the COC 7 Games 9 Optimal Sport System 14 Brand 18 Marketing Initiatives 20 Communications 24 Session, Hall of Fame and Heroes Tour 26 Education, Youth and Community Outreach 28 IOC Session, Commission Members 30 Canadian Olympic Foundation 32 Collaboration Through Sport 33 Board of Directors 34 Financial Statements 38 5 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT My dear friends in sport, 2011 was an outstanding year for the Canadian Olympic Committee. Coming off an Olympic year, it was very important to continue the momentum from Vancouver and to build on it. The power of the Olympic rings transcends sport and the COC has begun to leverage that power to build a better Canada. 2011 has been a year where we have begun to share a common vision and come together as a unified community. This is how we can be a best-in- class organization. There has been a fundamental shift in the focus of the COC. The focus of the entire organization is on the athletes. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CREDIBILITY SUSTAINABILITY YOUTH 2 Contents

ANNUAL CREDIBILITY REPORT SUSTAINABILITY 2020 YOUTH The IOC Annual Report is produced on a 100% recycled and carbon-balanced paper stock, and printed at a carbon-neutral printer. Front cover: In April 2020, just days after the postponement of the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020, the IOC set in motion the #StayStrong campaign – connecting athletes with the public through engaging and inspirational content generated by Olympians around the world. ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CREDIBILITY SUSTAINABILITY YOUTH 2 Contents CONTENTS Letter from President Bach 4 The IOC in 2020 6 Leading the Olympic Movement 8 The Olympic Movement 10 The International Olympic Committee 12 Olympic Agenda 2020 14 IOC President Addresses G20 Summit 15 Olympic Solidarity 16 National Olympic Committees 18 International Federations 20 Olympic Movement Partners 22 Olympic Broadcasting 28 Sustainability 32 Governance and Ethics 38 IOC Members 46 The COVID-19 Pandemic 52 Tokyo 2020 Postponement 54 IOC Support for the Olympic Movement 55 #StayStrong Digital Campaign 56 #StrongerTogether 57 Sport and Coronavirus Recovery 58 TOP Partners Support the Fight Against COVID-19 59 Celebrating the Olympic Games 62 Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 64 Preparations for Future Games 68 Future Hosts 73 Winter Youth Olympic Games Lausanne 2020 76 Future Youth Olympic Games 80 Sustainability, Legacy and the Olympic Games 82 IOC Annual Report 2020 Credibility, Sustainability, Youth 3 Supporting and Protecting Clean Athletes 86 Olympic Solidarity in 2020 88 Athlete Programmes 90 Fighting for Clean Sport 98 Supporting -

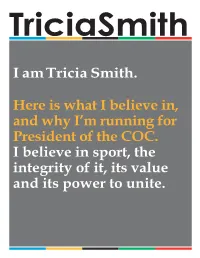

Biography Tricia SMITH

6 Biography Mrs Tricia SMITH Country CAN (Canada) Born 14 April 1957 Education Bachelor of Arts, International Relations, University of British Columbia (Canada) (1981); Bachelor of Laws, University of British Columbia (1985) Career Lawyer with Alexander, Holburn, Beaudin & Lang, Barristers & Solicitors (1986-1992); Deputy Manager and Partner with Barnescraig & Associates, dealing with Liability Claims, Claims Consulting, Risk Management and Sport Arbitration (1992-) Sports practised Rowing Sports career Four time Olympian and Silver medallist at the Olympic Games Los Angeles 1984; Gold medallist at the 1986 Commonwealth Games; Seven Time World Championship Medallist Sports administration Started Rowing Canada Aviron Athletes Committee (1978); Member first Canadian Olympic Committee (COC) Athletes Commission (1980-1983), Vice President (2009-2015) then President of the COC (2015-), Deputy President Ordinary Division, International Council of Arbitration for Sport (ICAS); Chair ICAS Membership Commission; Arbitrator, Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC); Chef de Mission at the 2007 Pan American Games; Member of the Bid Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games Vancouver 2010; Co Mayor of the Athletes Village at the Olympic Winter Games Vancouver 2010; Within the COC: former Team Selection Committee Chair, former Human Resources Committee Member, former Partner Relations Committee Chair, former Legal Committee Member, Former Women’s Commission Chair at the International Rowing Federation (FISA), Chair of the FISA -

2016 Annual Report

ROWING CANADA AVIRON ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Rowing Canada Aviron Head Office & National Training Centre 321 - 4371 Interurban Road Victoria, B.C,.V9E 2C5 Toll-Free: 1.877.722.4769 | Fax: 1.250.220.2503 National Training Centre 2070 Huron Street London, ON, N5V 5A7 T: 1.519.452.7213 rowingcanada.org facebook.com/rowingcanada | twitter.com/rowingcanada | instagram.com/rowingcanada.org IMAGE CREDITS: Kevin Light: cover page, pages 3, 5 (top), 7 (bottom, left), 11, 12, 13, 22, 23 Canadian Paralympic Committee: page 7 (right) David Jackson: page 10, 16, 17 World Rowing: page 18 Canadian Secondary Schools Rowing Association: page 18 ROWING CANADA AVIRON ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Table of Contents President’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 Treasurer’s Report 8 Provincial Director’s Report 9 2016 Results 10 Committee Report Umpires Committee 25 Safety and Events Committee 26 Royal Canadian Henley Regatta Joint Commission 27 In Recognition 28 Rowing Canada Aviron Board and Organization 29 Appendix 30 Financial Statements ROWING CANADA AVIRON ANNUAL REPORT 2016 President’s Report Mike Walker the membership for approval in January 2017. President, RCA • We continued to progress on building our fundraising strategy, establishing a Fundraising Cabinet and with large strides made in determining the strategy and methods for the Campaign. Some of the other notable policies and activities I am pleased to report to the Membership for the year approved and overseen by the Board during the past year 2016. The end of the Olympic and Paralympic include: quadrennial made 2016 a particularly busy year with • Amended the CARA by-laws to make it easier for intense preparations for the Games, on top of member clubs and associations to register to vote at the significant change throughout the organization. -

A History of Women's Competitive International Rowing Between 1954 and 2003

Paddling Against the Current: A History of Women's Competitive International Rowing Between 1954 and 2003 by Amanda Nicole Schweinbenz BA. Honours, The University of Western Ontario, 1999 MA., The University of Western Ontario, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Human Kinetics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June 2007 © Amanda Nicole Schweinbenz, 2007 11 Abstract In 1954, the Federation International Societes d'Aviron (FISA) hosted the first Women's European Rowing Championships in Macon, France. Although FISA had never before formally recognized women's competitive international rowing, oarswomen around the world had been active participants for years, competing not only in local and national regattas, but international as well. Despite the historical evidence that women could indeed race at an international level, FISA delegates, all of whom were men, saw fit to curtail women's international participation by shortening the women's racing distance to half of that required of the men and restricting the number and types of events in which women raced. While international oarswomen were limited, these constraints were not completely restrictive. Rather, the introduction of women's races at the European championships created opportunities for oarswomen to display publicly their physical and athletic capabilities while challenging social and historical discourses regarding appropriate female appearance and athletic participation. Since this inaugural event in 1954, female athletes, coaches, and administrators have sought to achieve gender equity in a sport typically associated with men and masculinity. Female rowing enthusiasts pressed to increase opportunities for all oarswomen by negotiating with male sporting administrators to have women's competitive international rowing recognized on the same level as men's rowing. -

Rowing Sport Update

Rowing Sport Update December 2020 About this Sport Update Published in December 2020, the series of Sport Updates offer a summary of competition-related material about each sport at Tokyo 2020 and provide a variety of information to help teams in their planning and preparation for the Games. General information such as accreditation, accommodation, transport, COVID-19 countermeasures, etc., is not included as it is still in the process of being finalised, but interim information relating to these areas is continually being published on Tokyo 2020 Connect as it is confirmed. All information provided in this Sport Update was correct at the time of publication, but some details may have changed prior to the Games. NOC representatives are advised to regularly check the IOC’s NOCnet and Tokyo 2020 Connect for the latest updates, especially regarding competition schedules. Team Leaders’ Guides explaining Games-time plans for sports in greater detail will be distributed to NOCs in May 2021. © The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games WELCOME On behalf of the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, I am delighted to present the Rowing Sport Update for the Games of the XXXII Olympiad. We have been working diligently to provide facilities, services and protocols which will allow everyone involved in the Games to achieve all three of Tokyo 2020’s core concepts: achieving personals bests, unity in diversity, and connecting to tomorrow. Included is information about: • processes relating to competition and training • key dates and personnel • competition schedule, format and rules • venue facilities and services We trust it will assist you with your planning for the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020. -

I Am Tricia Smith. Here Is What I Believe In, and Why I'm Running For

TriciaSmith I am Tricia Smith. Here is what I believe in, and why I’m running for President of the COC. I believe in sport, the integrity of it, its value and its power to unite. Stable, credible leadership as a four time I believe that leadership based on respect, Olympian, successful entrepreneur and integrity and collaboration is critical. We businesswoman, long term national and will create a community that attracts and international sport administrator and lawyer. supports the best in leadership. I will re-establish the ethics and values of the COC through inclusive and collaborative leadership built on a foundation of respect and integrity. I have provided stable, credible leadership to the COC on the front line during these turbulent times The Scrapbook and will continue to see this through to recovery I know the Olympic movement from the grass roots to the and beyond. Under my leadership, I have dealt with international stage. My lifetime of experience in the sport the immediate challenges, and with my team, put a system in Canada and internationally includes being an athlete review in place to identify issues within the on four Olympic Teams, an Olympic silver medalist, a seven organization, extended the review to include time world championship medalist and Commonwealth games governance and have authored a plan to address gold medalist, a member of the Executive Committee and Vice outcomes. president of the COC, a member of the OTP Board, a member of the International Council of Arbitration for Sport, Deputy The COC will be a world leader in harassment President of the Ordinary Division and Chair of the free organizations.