Messapian Stelae: Settlements, Boundaries and Native Identity in Southeast Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Guided Cycling Tour

Independent ‘Self-guided’ cycling tour Puglia: Heel of Italy, Heart of the Mediterranean Discover the south-east of Italy, unique countryside between the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea TRIP NOTES 2021 © Genius Loci Travel. All rights reserved. [email protected] | www.genius-loci.it ***GENIUS LOCI TRAVEL - The Real Spirit Of Italy*** Independent ‘Self-guided’ cycling tour INTRODUCTION Stretching out for over 300 km along the Adriatic Sea, Puglia is Italy’s easternmost region, divided from the Albanian coast by a mere 80 km strip of ocean. As only a very small part of its territory can be considered mountainous it is also the flattest region in the country and, therefore, especially suitable for bicycle touring. For centuries Puglia has been under strong Greek and oriental influences, resulting in a unique mix of east and west that can be found in several aspects of the region’s culture, from the typical ‘pizzica’ dance to the Greek and Albanian dialects still spoken in some of the area’s most remote villages. From the ‘trulli’ of Alberobello over the imposing Castel del Monte at Andria, to the baroque ‘palazzi’ and churches of Lecce; from the Gargano National Park over the plains of the Tavogliere delle Puglie, around Lucera and Foggia, to the peninsula of the Salento in the south - Puglia has much to offer to the alert tourist willing to invest some time to explore and discover this region. The tour will take you through the idyllic coastal regions along the Adriatic and Ionic Seas, past old gnarled olive trees, slowly threading your way down from north to south. -

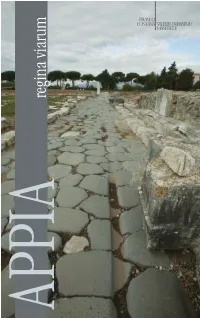

Franco Fontana Valerio Massimo Manfredi

FRANCO FONTANA VALERIO MASSIMO MANFREDI FRANCO photographs FONTANA VALERIO MASSIMO MANFREDI story: regina viarum regina viarum regina viarum 7 First came a route which marked the social and economical history of a complex country called the U.S.A., then a trail, laboriously trodden by European pilgrims since the year one thousand, and now a road belonging to the ancient world, one of the main commercial and cultural routes of the Roman Empire. The Appian Way is the last protagonist of a trilogy narrating the routes covered by a group of friends with a common passion for travelling. Once again the pictures of photographer Franco Fontana and the words of writer Valerio Massimo Manfredi, expert of ancient history, have succeeded in capturing the essence of a route whose fascination is rooted the very origins of our country. My personal participation in this journey and Transmec Group’s involvement in the project go further than simple sponsoring; we have, rather, taken a concept and brought it to life; developed, studied and accomplished an idea through modern forms of expression. Transmec has always been attentive to requests and proposals coming from the world of art and culture, offering our support to novel ideas and to their promoters. A commitment which rises directly from the fundamental features of a company operating worldwide: an innovative spirit and the ability to keep up with the times. This volume personifies the close relationship that exists between our work, transport, expeditions, global communication and photography: the ability to connect people and things which are far away from each other; to erase distances and spread ideas, facts and events. -

Sistema Informativo Ministero Della Pubblica Istruzione

SISTEMA INFORMATIVO MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA PUGLIA UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE : BRINDISI ELENCO DEI TRASFERIMENTI E PASSAGGI DEL PERSONALE DOCENTE DI RUOLO DELLA SCUOLA PRIMARIA ANNO SCOLASTICO 2014/15 ATTENZIONE: PER EFFETTO DELLA LEGGE SULLA PRIVACY QUESTA STAMPA NON CONTIENE ALCUNI DATI PERSONALI E SENSIBILI CHE CONCORRONO ALLA COSTITUZIONE DELLA STESSA. AGLI STESSI DATI GLI INTERESSATI O I CONTROINTERESSATI POTRANNO EVENTUALMENTE ACCEDERE SECONDO LE MODALITA' PREVISTE DALLA LEGGE SULLA TRASPARENZA DEGLI ATTI AMMINISTRATIVI. TRASFERIMENTI NELL'AMBITO DEL COMUNE - CLASSI COMUNI 1. BARBARELLO FRANCESCA . 20/ 7/67 (BR) DA : BREE03201C - II CIRC.-GIOVANNI XXIII-MESAGNE (MESAGNE) A : BREE03101L - I CIRCOLO-G.CARDUCCI-MESAGNE (MESAGNE) (SOPRANNUMERARIO TRASFERITO CON DOMANDA CONDIZIONATA) PUNTI 102 2. CAGNAZZO CATIA . 8/ 8/74 (BR) DA : BREE817019 - CIRCOLO G.CALO'-BRINDISI (BRINDISI) A : BREE813012 - CIRCOLO C.COLLODI-BRINDISI (BRINDISI) (SOPRANNUMERARIO TRASFERITO CON DOMANDA CONDIZIONATA) PUNTI 112 3. CARBONE MARIANTONELLA . 7/ 5/65 (BR) DA : BREE82701X - CIRC.-DE AMICIS-FRANCAVILLA (FRANCAVILLA FONTANA) A : BREE82701X - CIRC.-DE AMICIS-FRANCAVILLA (FRANCAVILLA FONTANA) DA POSTO DI SOSTEGNO :MINORATI FISIOPSICHICI PUNTI 106 4. CARLUCCIO ROSITA . 9/12/74 (BR) DA : BREE81001E - BOZZANO (BRINDISI) A : BREE81001E - BOZZANO (BRINDISI) DA POSTO DI LINGUA :INGLESE PRECEDENZA: TRASFERITO NELL'AMBITO DELL'ORG. FUNZ. PUNTI 122 5. CARONE TIZIANA . 22/10/69 (BR) DA : BREE81401T - PRIMARIA G.B. PERASSO (BRINDISI) A : BREE83501V - S.LORENZO CIRCOLO BRINDISI (BRINDISI) PUNTI 125 6. CITO MARIA IMELDA LILIA . 4/ 9/55 (BR) DA : BREE82901G - CIRC.-G.BOSCO-CEGLIE M.CO (CEGLIE MESSAPICA) A : BREE82801Q - EDMONDO DE AMICIS (CEGLIE MESSAPICA) PUNTI 278 TRASFERIMENTI NELL'AMBITO DEL COMUNE - CLASSI COMUNI 7. -

Manifesto Liste Francavilla Fontana

COMUNE DI FRANCAVILLA FONTANA Liste dei candidati per l’elezione diretta alla carica di sindaco e di n. 24 consiglieri comunali che avrà luogo domenica 10 giugno 2018 (Articoli 72 e 73 del decreto legislativo 18 agosto 2000, n. 267, ed art. 34 del testo unico 16 maggio 1960, n. 570, e successive modicazioni) 1) Maurizio 2) Giuseppe 3) Giovanni 4) Antonello 5) Pietro BRUNO RICCHIUTI TAURISANO DENUZZO IURLARO nato a nato a nato a nato a nato a Francavilla Fontana (BR) il 13/11/1966 Francavilla Fontana (BR) il 05/02/1977 Oria (BR) il 19/09/1953 Mesagne (BR) il 14/11/1976 Francavilla Fontana (BR) il 27/03/1961 CANDIDATO ALLA CARICA DI SINDACO CANDIDATO ALLA CARICA DI SINDACO CANDIDATO ALLA CARICA DI SINDACO CANDIDATO ALLA CARICA DI SINDACO CANDIDATO ALLA CARICA DI SINDACO LISTE COLLEGATE LISTA COLLEGATA LISTE COLLEGATE LISTE COLLEGATE LISTE COLLEGATE LISTA N. 1 LISTA N. 2 LISTA N. 3 LISTA N. 4 LISTA N. 5 LISTA N. 6 LISTA N. 7 LISTA N. 8 LISTA N. 9 LISTA N. 10 LISTA N. 11 LISTA N. 12 LISTA N. 13 LISTA N. 14 LISTA N. 15 LISTA N. 16 LISTA N. 17 Alfredo IAIA Giovanni CAPUANO (detto Ivan) Alfonso ANDRIULO Luigi GALIANO Gianpiero ANDRIULO Giovanni BUNGARO (detto Giancarlo) Rocco Giuseppe ARGENTIERO Michele IAIA Cosimo AMMATURO (detto Mimmo) Euprepio CURTO (detto Uccio) Maria ANGELOTTI Francesco AMELIO Silvana AMMATURO Giuseppe PISCONTI Antonio CAMARDA Rosaria APRILE Luigi SEMERARO nato a Francavilla Fontana (BR) il 11/03/1958 nato a Francavilla Fontana (BR) il 24/04/1968 nato a Francavilla Fontana (BR) il 27/10/1986 nato a Mesagne (BR) il 01/04/1977 -

Le Lucerne Di Età Romana Dai Contesti Di Brundisium E Gnatia

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI ‘FEDERICO II’ DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE ARCHEOLOGICHE E STORICO-ARTISTICHE XXII CICLO CURRICULUM DI ‘ARCHEOLOGIA DELLA MAGNA GRECIA’ ______________________________________________________________________ TESI DI DOTTORATO LE LUCERNE DI ETÀ ROMANA DAI CONTESTI DI BRUNDISIUM E GNATIA Coordinatore Chiar.mo Prof. Carlo GASPARRI Tutor Dottoranda Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Raffaella CASSANO Rosa CONTE ___________________________________________________________________ ANNO ACCADEMICO 2008-2009 INDICE INTRODUZIONE p. 1 I. BRUNDISIUM E GNATIA: IL QUADRO POLITICO E ISTITUZIONALE 7 II. BRUNDISIUM. I CONTESTI FUNERARI 18 II.1. Necropoli nord-occidentale 19 II.2. Necropoli occidentale 24 II.3. Composizione dei corredi funerari 35 II.3.1 Le lucerne 44 III. CATALOGO 58 III.1. Le lucerne dai corredi funerari 59 A. Lucerne di età repubblicana 61 B. Lucerne di età imperiale 87 III.2. Le lucerne dagli ‘scarichi’ della necropoli 123 A. lucerne di età repubblicana 124 B. lucerne di età imperiale 150 IV. GNATIA. I CONTESTI FUNERARI 160 IV.1 Necropoli occidentale 161 IV.2 Necropoli meridionale 173 IV.3 Composizione dei corredi funerari 179 IV.3.1. Le lucerne 191 V. CATALOGO 198 V.1. Le lucerne dai corredi funerari della necropoli occidentale 199 A. lucerne di età repubblicana 200 B. lucerne di età imperiale 230 V.2. Le lucerne dai corredi funerari della necropoli meridionale 246 A. lucerne di età repubblicana 247 B. lucerne di età imperiale 260 VI. GNATIA. I CONTESTI DI ABITATO 267 VI. 1. L’area della basilica episcopale 268 VI. 2. Il quartiere a Sud della via Traiana. 277 . VII. CATALOGO 285 VII.1. Le lucerne dall’area della basilica episcopale 286 A. -

POUILLES DU SUD Des « Trulli » D’Alberobello À La Mer 7Jours / 6 Nuits / 5 Jours De Randonnée Et De Visites

POUILLES DU SUD Des « trulli » d’Alberobello à la mer 7jours / 6 nuits / 5 jours de randonnée et de visites GROUPE MARTIN CLUB ALPIN DE NICE Du diamnche 19/09 au samedi 25/09/2021 « La Puglia » : une terre aux mille facettes, on emploie encore parfois le pluriel «Le Puglie» en italien, pour évoquer les multiples microcosmes qui se juxtaposent et qui confèrent à cette région une identité complexe. Des paysages tourmentés faits de pierre calcaire, de terre rouge, d’arbres majestueux, de lits d’anciens torrents asséchés et de vastes plaines cultivés. L’Apulie des romains est, depuis l’antiquité, à l’opposé de ses voisins du Mezzogiorno, une région riche et prospère. Elle s’étend tout au sud de l’Italie, dans le « talon de la botte », le long des mers Ionienne et Adriatique. A partir de Bari, où se juxtaposent influences byzantine, arabe, gothique ou baroque de ses monuments, vous partirez à la découverte de ce pays aux paysages variés, des villages baroques du Val d’Itria et des fameux « trulli » d’Alberobello, ces curieuses petites maisons blanchies à la chaux et aux toits coniques jusqu’aux plages de sable fin d’Ostuni « la blanche », résolument tournée vers l’Orient, Lecce la « Florence baroque du Sud et Otranto face à la mer. 1 PROGRAMME INDICATIF : 12/09/2021 : Vol Paris - Bari. Accueil à l’aéroport, découverte du centre historique, Basilique de San Nicola, Duomo de San Sabino, Castello. Nuit en hôtel*** à deux pas de la vieille ville en B&B. 13/09/2021 : Randonnée en bord de mer. -

Verso Il Contratto Di Fiume Del Canale Reale (BR)

Servizio Urbanistica - SUE Verso il Contratto di Fiume del Canale Reale (BR) Avvio consultazione pubblica del “Dossier di conoscenza del Canale Reale” Primo progetto pilota della Regione Puglia Con la presente comunicazione si avvia la consultazione pubblica del “Dossier di conoscenza del Canale Reale”, in modalità remota, considerate le condizioni emergenziali che ancorano limitano le occasioni di confronto diretto. Con la consultazione pubblica, alla quale sarà data la più ampia diffusione anche mediante la pagina Facebook Contratto di Fiume – Canale Reale, si potranno raccogliere le indicazioni, da parte dei portatori d’interesse, sulla percezione del quadro conoscitivo ricostruito, anche in termini di condivisione o integrazione delle risorse, criticità e proposte già individuate in materia di riqualificazione del contesto fluviale. Gli elaborati del Dossier di conoscenza (Relazione e Tavole) sono stati resi disponibili al link seguente: https://politecnicobari- my.sharepoint.com/:f:/g/personal/carlo_angelastro_poliba_it/EibqJYky33ZOvDaoD3KH0J0BON1x8N6zXx7k FGeSuOkfZg?e=xD52Nf In allegato alla presente è disponibile il Modulo di Condivisione e/o Osservazioni dell'Analisi Conoscitiva, in formato editabile per la compilazione. La consultazione pubblica ha la durata di un mese a partire dalla data di invio della presente comunicazione, e condurrà, successivamente al periodo indicato, alla approvazione del Dossier di conoscenza. Gli ulteriori contributi eventualmente pervenuti saranno allegati al Dossier di conoscenza e presi in considerazione nella definizione del Documento strategico. Il modulo compilato dai portatori di interesse potrà essere inviato all’indirizzo email [email protected] ed in copia conoscenza all’indirizzo email [email protected]. Per maggiori informazioni rivolgersi al Geom. Antonio CAPODIECI – Servizio Urbanistica e Ambiente – tel. -

SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO – SO “N. MELLI”: Dott. SPEDICATI LUIGI

SERVIZIO SANITARIO NAZIONALE REGIONE PUGLIA AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE DELLA PROVINCIA DI BRINDISI N. 2788 GC del Registro delle Deliberazioni N. Proposta PDL 3331-11 UFFICIO PERSONALE PRESIDIO OSPEDALIERO“Brindisi-Mesagne-San Pietro Vernotico” OGGETTO : SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO – S.O. “N. MELLI” : Dott. SPEDICATI LUIGI : pagamento compenso per attività resa, in regime libero-professionale di Biologo – (attività di lavoro autonomo). Periodo: APRILE – MAGGIO - GIUGNO 2011 Il giorno ___07/11/2011__ presso la sede della A.S.L. BR, sita in Brindisi alla via Napoli n.8, sull’argomento in oggetto, il responsabile della posizione organizzativa “Funzioni amministrative” Rag. Federico Bianco, e il Dirigente Medico Dr. Antonino La Spada dello S.O. “N. Melli” di San Pietro Vernotico, a seguito dell’istruttoria effettuata dalla Rag. Maria Regina Perlangeli, Collaboratore Amministrativo, e che con la sottoscrizione della presente proposta viene confermata dai Direttori Amministrativo, Dott. A. Pastore e Sanitario Dott. A. Piro del P.O. Brindisi – Mesagne – San Pietro Vernotico, relazionano quanto segue: PREMESSO CHE: -CON PROVVEDIMENTO n.2887 del 24/10/2006 è stato istituito l'Albo Aziendale per i Biologi libero- professionisti, autorizzando i Dirigenti Responsabili dei Laboratori Analisi degli Stabilimenti Ospedalieri Aziendali a far ricorso ai nominativi inseriti nel predetto Albo, nei casi strettamente necessari, al fine di assicurare i turni di Pronta Disponibilità nelle UU.OO. interessate. -CON DELIBERAZIONE n.212 del 31/01/2007 il suindicato Albo è stato integrato con l'inserimento di nuovi nominativi di Dirigenti biologi. -CON DELIBERAZIONE n.2887/06 è stato stabilito che ai Biologi in questione sarà corrisposto lo stesso compenso stabilito dalle vigenti norme contrattuali in materia di pronta disponibilità e,in caso di chiamata,l’attività prestata viene computata come lavoro straordinario e, quindi, remunerata con le stesse aliquote di straordinario previste per il personale dipendente. -

Latiano - Mesagne - Cittadella) - BRINDISI + Z

-/'t.Pbnnoij'i AUTOLINEA: CISTERNINO - (Speziale - Montalbano) - OSTUNI - CAROVIGNO - S.VITO - (Latiano - Mesagne - Cittadella) - BRINDISI + Z. I. ORARI IN VIGORE DAL 15 GENNAIO 2018 (*) (*) (*) (*) (*) (*) Annuale Annuale Annuale Non Scol Annuale Annuale Non Scol L/V L/S L/V L/V L/V L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/S L/V L/S Cisternino (P.za Navigatori) 4:10 5:05 6:10 6:10 6:20 6:20 6:35 6:35 7:20 8:15 Cisternino (Ist. Pedagogico) 4:20 5:15 6:20 6:20 6:45 6:45 7:30 8:25 6:30 6:30 Speziale 6:40 6:40 Montalbano 6:45 6:45 Ostuni (V.le A.Moro) Ostuni (V.le dello Sport) (perc. A) 5:40 6:25 6:25 6:55 7:35 7:45 Ostuni (V.le A.Moro) 5:42 6:27 6:27 6:57 7:37 7:47 Ostuni (P.za Italia) (perc. B) 4:35 5:30 5:45 6:35 6:35 6:30 6:30 7:00 7.00 7:00 7:00 7:00 7:00 7:40 7:40 7:45 7:50 8:45 Carovigno (Via Extr. S.Sabina) (perc.A) 6:40 6:40 7:00 7:00 Carovigno (C.so Umberto) (perc.B) 4:45 5:40 5:55 6:45 6:45 7:10 7:10 7:10 7:10 7:10 7:10 7:05 7:05 7:50 7:50 7:55 8:00 S.Vito dei N.ni (Via Carovigno) (perc.A) 4:50 5:45 6:05 6:55 6:55 6:55 6:55 7:20 7:20 7:20 7:20 7:20 7:20 7:15 7:15 8:00 8:05 8:10 8.10 S.Vito dei N.ni (Via Francavilla) (perc. -

Elenco Candidati Ammessi Alla Selezione

$OOHJDWR´&µ 3529,1&,$',%5,1',6, (/(1&2&$1','$7,$00(66,$//$6(/(=,21( 1 &2*120( 120( 1$6&,7$ $00,66,21( 1 Alibrando Teodoro Massimo 13/12/66 Brindisi 2 Alibrando Gianfranco 22/10/77 Mesagne 3 Altomare Giuseppe 16/07/68 Brindisi 4 Amaro Marcello 15/04//80 Brindisi 5 Angolano Cinzia 02/11/1978 Brindisi Ammessa con riserva 6 Attanasi Nicole 31/07/88 Brindisi 7 Baccaro Giacomo 10/01/71 Fasano 8 Bari Stefania 09/09/83 S.Pietro V.co 9 Bellanova Salvatore 16/08/69 Brindisi 10 Bellanova Fabio 05/02/78 Brindisi 11 Bianco Annagrazia 01/09/80 S. Pietro V.co 12 Bonatesta Salvatore 31/05/84 Ceglie 13 Cacumi Manuela 15/03/78 Mesagne 14 Caforio Angelo 29/07/73 Manduria 15 Caliolo Angelo 27/04/57 Carovigno 16 Calò Tiziana 27/05/66 Brindisi 17 Calo’ Terence 07/02/83 S.Pietro V. Co 18 Campolattano Marisa 05/02/71 Bari 19 Cappelletti Pierluigi 28/02/73 Brindisi 20 Carbone Annibale 29/05/75 Oria 21 Carlucci Monia 28/09/80 Brindisi 22 Carrozzo Samanta 15/03/74 Moutier 23 Carusi Ilaria 02/08/78 Mesagne 24 Casella Francesco 05/05/57Rutigliano 25 Cavallo Pietro 19/09/77 Brindisi 26 Cavallo Francesco 31/03/88 Ostuni 27 Cesaria Clelia 05/10/84 Cisternino 28 Cesaria Luigi 25/09/56 Carovigno 29 Ciccolella Alessandro 12/04/66 Brindisi 30 Conte Giovanni 03/10/75 Brindisi 31 Convertino Francesco 09/09/79 Tomezzo (UD) 32 Cosi Gianluigi 24/03/76 Brindisi 33 Costantini Marcello 28/03/65 Ehingen 34 Costantini Giovanni 18/11/73 Mesagne 35 D’Elia Giacinto 23/06/80 Francavilla F.na 36 Dalloni Francesco 23/09/82 Ostuni 37 Damasco Marco 13/05/85 Brindisi 38 De Filippis Manolo 21/09/73 S. -

Servizio Sanitario Nazionale

SERVIZIO SANITARIO NAZIONALE REGIONE PUGLIA AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE DELLA PROVINCIA DI BRINDISI N. __2389___ del registro delle deliberazioni N. prop._ _2798-19__ DISTRETTO SOCIO SANITARIO N.3 DI FRANCAVILLA FONTANA OGGETTO: Rivalutazione e autorizzazione dei Piani Assistenziali Individualizzati dei Sigg. C.D. ( nato a Villa Castelli il 24/01/1959 ) D.S.M. ( nata a Zofingen (CH) il 06/02/1982 ) e V.R.C. ( nato a San Michele Salentino il 08/12/1957 ) in carico presso la R.S.S.A Disabili ex art.58 R.R. n.4/2007 “Casa Melissa ”sita a Mesagne. Impegno di spesa 2019. Il giorno....19/12/19....presso la sede della Azienda Sanitaria Locale BR sita in Brindisi, alla via Napoli, 8, Sull'argomento in oggetto il Direttore del Distretto S.S. n. 3 di Francavilla Fontana dr. Francesco Galasso, a seguito dell'istruttoria effettuata dall‘ Assistente Sociale Dott.ssa Angela Vitale, che con la sottoscrizione della presente proposta viene confermata, relaziona quanto appresso: Preso atto delle richieste di proroga dei Piani Assistenziali Individualizzati presentate dai familiari e/o rappresentanti legali, si è proceduto alla rivalutazione sociosanitaria per continuità assistenziale dei Sigg. C.D.( nato a Villa Castelli il 24/01/1959) D.S.M.(nata a Zofingen (CH) il 06/02/1982) e V.R.C. ( nato a San Michele Salentino il 08/12/1957 ) ospiti presso la struttura R.S.S.A Disabili ex art. 58 R.R. n.4/2007 Casa Melissa ” sita a Mesagne . Visto che l’ U.V.M. Distrettuale di Francavilla Fontana nelle sedute del 23/11/2018, del 09/01/2019 e del 22/08/2019 ha rivalutati i PAI esprimendo parere favorevole alla proroga per continuità assistenziale dei Sigg. -

Agostinelli Maria Cristina 12/07/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR)

Agnello Antonio 29/01/1978 MESAGNE (BR) Agostinelli Maria Cristina 12/07/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Agostinelli Nicola 13/08/1974 BRINDISI (BR) Agrimi Anna 28/07/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Agrimi Carlo 10/06/1978 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Akinwande Muritala Alani 23/10/1971 NIGERIA (EE) Albanese Danilo 27/04/1982 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Albanese Stefania 20/09/1978 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Alfarano Alessandra 04/10/1980 CAMPI SALENTINA (LE) Allegrini Catia 07/11/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Allegrini Daniela 24/05/1981 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Allegrini Francesca 22/05/1983 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Allegrini Simona 02/03/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Altavilla Giuliano 29/03/1977 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Alula Andrea 05/08/1979 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Alula Cosimo 02/12/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Alula Emanuela 11/09/1984 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Alula Gianpiero 28/04/1978 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Ancora Giulio 12/02/1974 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Ancora Giuseppe 05/02/1975 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Ancora Stefania 21/07/1980 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Andriani Allison Lucia 19/12/2010 BRINDISI (BR) Andriani Antonella 26/04/1977 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Andriani Elena 06/05/1987 CAMPI SALENTINA (LE) Andriani Iolanda 29/10/1981 FRANCAVILLA FONTANA (BR) Andriani Maria Grazia 06/07/1970 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Andriani Mattia Pietro 28/09/2009 BRINDISI (BR) Andriani Maurizio 29/04/1976 SAN PIETRO VERNOTICO (BR) Andriani Swamy Federica 29/03/2007 BRINDISI (BR) Andriescu Alina Petronela 30/06/1985 ROMANIA (EE) Andrioli