Discovering the Holy Land's Historic Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 144 3rd International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2017) Social and Historical Environment of the Society of Moscow Artists Elena Lomova Moscow State Academic Art Institution named after V.I. Surikov Moscow, Russia Abstract—The article is concerned with the social and later became the first chairperson of the Society of Moscow historical conditions of forming the Society of Moscow Artists Artists (OMKh). Grabar shared similar vision of art as (OMKh), whose members had covered a long way from an painters from Mir Iskusstva, who popularized the epatage art group the Jack of Diamonds to the society standing individualism, the disengagement of art from political and at the origins of Socialist Realism. socials issues, and paid particular attention to the legacies of the past and especially to Russia‘s national cultural traditions. Keywords—OMKh; The Jack of Diamonds; futurists; The group‘s ‗leftists‘, where the ―Russian avant-garde‖ Socialist Realism; art societies in the 1920s and 1930s occupied a special place, had shaken even more the conventional assumptions about art, dramatically influencing I. INTRODUCTION further development of world art. th The first half of the 20 century was rich in the landmark Meantime, Russian art continued to shift away from the events that could not but influence art, one of the most reality to a non-figurative world, as if not wishing to reflect sensual areas of human activity, sensitive to the slightest horrors happening in the country. Whereas the artists from fluctuations in public life. We can trace their obvious Mir Iskusstva were dipping into the dreams of the past, the repercussions in art while considering the historical events of th avant-garde artists were generally anxious for the future and the early 20 century. -

Emergency in Israel

Emergency in Israel Emergency Update on Jewish Agency Programming May 16, 2021 The recent violent events that have erupted across the country have left us all surprised and stunned: clashes with Palestinians in Jerusalem and on the Temple Mount; the deteriorating security tensions and the massive barrage of missiles from Gaza on southern and central Israel; and the outbreak of unprecedented violence, destruction, and lynching in mixed cities and Arab communities. To say that the situation is particularly challenging is an understatement. We must all deal with the consequences of the current tensions. Many of us are protecting family, coworkers, or people under our charge while missiles fall on our heads night and day, forcing us to seek shelter. We have all witnessed the unbearable sights of rioting, beating, and arson by Arab and Jewish extremists in Lod, Ramla, Acre, Kfar Qassem, Bat Yam, Holon, and other places. As an organization that has experienced hard times of war and destruction, as well as periods of prosperity and peace, it is our duty to rise up and make a clear statement: we will support and assist populations hit by missile fire as we did in the past, after the Second Lebanon War and after Operations Cast Lead and Protective Edge. Together with our partners, we will mobilize to heal and support the communities and populations affected by the fighting. Our Fund for Victims of Terror is already providing assistance to bereaved families. When the situation allows it, we will provide more extensive assistance to localities and communities that have suffered damage and casualties. -

Noa Yekutieli

NOA YEKUTIELI Born in 1989 in the USA. Lives and works in Tel-Aviv and Los Angeles. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019 Kunstverein Augsburg, Germany (upcoming) 2019 Track 16 Gallery, Los Angeles, USA (upcoming) 2018 Modern Portrait, New Position, Art Cologne, with Sabine Knust Galerie, Cologne, Germany 2017 The Other Side, Public Art Installation, Los Angeles, USA 2017 Meeting Place, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2017 Fractured Water, Israeli-Palestinian Pavilion, Nakanojo Biennale, Nakanojo, Japan 2015 Transitions, Open Contemporary Art Center, Taipei, Taiwan 2015 Particles, Treasure Hill Artist Village, Taipei, Taiwan 2015 Around The Cracks, Sommer Frische Kunst, Bad Gastein, Austria 2015 While They Were Moving, They Were Moved, Gordon ll Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel 2015 Reflecting On Shadows, Artist House, Tel Aviv, Israel 2015 Uncontainable, Janco Dada Museum, Ein Hod, Israel 2015 What Doesn't Bend Breaks, Gallery Schimming, Hamburg, Germany 2015 The Magnifying Glass and the Telescope, p/art, Hamburg, Germany 2014 Through The Fog, The Distance, Wilfrid Museum, Kibbutz Hazorea, Israel 2013 Between All Our Intentions, Dwek Gallery, Mishkenot Sha’ananim, Jerusalem, Israel 2013 Incorporeal Reality, with Yael Balaban, Marina Gisich Gallery, St. Petersburg, Russia 2013 1952, Special installation project, Fresh Paint art fair, Tel-Aviv, Israel 2013 1952, Givat Haim Gallery, Givat Haim Ehud, Israel 2013 A Document of a Passing Moment, Artstation Gallery, Tel-Aviv, Israel 2012 Baggage, Al Ha'tzuk Gallery, Netanya, Israel -

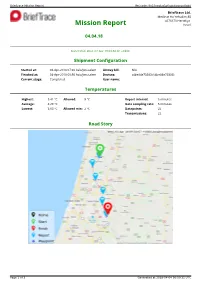

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

"Acquisitions and Loans

2 Alexander Bogomazov Forest. Boyarka 3 Alexander Bogomazov Self Portrait 4 Alexander Bogomazov Caucasus 5 Ilya Chashnik The Seventh Dimension 6 Vasily Ermilov Composition with letters 7 Vasily Ermilov 10th anniversary Exhibition of Books and Press of the Ukraine 8 Natalia Goncharova L’Arbre Rose Printemps 9 Natalia Goncharova Spanish Woman 10 Boris Grigoriev A Street in Paris 11 Boris Grigoriev Dachnitsa 12 Boris Grigoriev Woman peering behind the screen 13 Pyotr Konchalovsky Pines 14 Alexander Kuprin Still Life with a Sculpture of B. D. Korolev 15 Mikhail Larionov Young Jester 16 Vera Pestel Constructivist Composition 17 Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin Cafe |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||18 Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin The Artist’s Daughter Elena 19 Liubov Popova Painterly architectronic 20 Liubov Popova Painterly architectronic 21 Alexander Rusakov Still Life with a Samovar and a Flower 22 Nadezhda Udaltsova Pictorial Architecture 23 Alexander Volkov Nude in a Mountainous Landscape 24 Alexander Volkov Golgotha 25 Alexander Volkov Eastern Fantasy 26 Mikhail Vrubel Portrait of Vova Mamontov reading 'Acquisitions and Loans' Opening Exhibition BUTTERWICK GALLERY, OPENING EXHIBITION IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII BUTTERWICK GALLERY, OPENING EXHIBITION IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Alexander Bogomazov Forest. Boyarka 1880-1930 1915 Sanguine on paper, 32 x 26 cm Signed and dated lower right ‘1915 A. B.’ Provenance ▪ The family of the artist, Kiev ▪ S. I. Grigoriants, -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

The Ethiopian Israeli Artist Whose 'Black Art' Gives Power To

11/05/2019, 1325 Page 1 of 1 Log in Subscribe now Saturday, May 11, 2019. Search Iyyar 6, 5779 Time in Israel: 3:11 PM Israel News All sections Teva - U.S. U.S. - Iran Israel - Gaza 747 Erdogan Iran - U.S. Eurovision 2019 Jerusalem holds off evicting gallery Haaretz | News A photo album Haaretz | News Istanbul shatters Haaretz | News Vicious protests that hosted anti-occupation NGO from the State of Israel’s first Erdogan’s dream at Israeli-Palestinian memorial year are a sign of Israel's demise Recommended by Home > Israel News Trending Now The Ethiopian Israeli Artist Whose 'Black Art' Gives Power to Greedy Jews and Why Does Hannah the People 'Lovely Bitches': Arendt's 'Banality of Nirit Takele says she has always painted about the disadvantaged Israel’s Eurovision Evil' Still Anger Ethiopian community; it’s not some stream of ‘black art’ shown for Video Draws Fire Israelis? the trendy in New York or London Vered Lee | Send me email alerts May 10, 2019 8:51 PM Share Tweet Zen Subscribe 40 U.S. States Sue What Happened Teva for 'Multi-billion When Palestinian Dollar Fraud on the Women Took Charge American People' of Their Village Israeli artist Nirit Takele, April 2019. Credit: Meged Gozani ● The Ethiopian music scene in Israel begins to take center stage ● 'It was meant to be an African party in Tel Aviv. But I was the only African there' ● Hot, black Israeli rap duo bubbles over on YouTube In the past month Nirit Takele secluded herself in the studio of her home in north Tel Aviv and painted intensively for 10 to 16 hours a day. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

2009 High School in University! Shachar Jerusalem and Is a Ninth Grader Is Sponsored by at the Menachem the NACOEJ/EDWARD G

Sponsorships Encourage Students to Develop Their Potential Sponsorships give Ethiopian students the chance to gain the most out of school. In some cases, students’ talents become a gift for everyone! The outstanding examples below help us understand how valuable your contributions are. Sara Shachar Zisanu Baruch attends the Dror has a head start on SUMMER 2009 High School in university! Shachar Jerusalem and is a ninth grader is sponsored by at the Menachem THE NACOEJ/EDWARD G. VICTOR HIGH SCHOOL SPONSORSHIP PROGRAM Marsha Croland Begin High School of White Plains, in Ness Ziona. In NY. Sara has just fi fth grade, he took fi nished eleventh a mathematics course by correspondence Sponsors grade and is ac- through the Weizmann Institute for Sci- tive as a counselor in the youth move- ence. Since then, he has been taking ment HaShomer Hatzair, affi liated with special courses in math and science, won Give and the kibbutz movement. Sara has been a fi rst-place in the Municipal Bible contest member of the group since she was nine in sixth grade, and took second-place in years old and was encouraged to become a the Municipal Battlefi eld Heritage Con- Ethiopian counselor by her own counselor last year. test (a quiz on Israeli military history) Sara appreciates the values of teamwork, in seventh grade! Currently, Shachar is in independence, and positive communica- an advanced program for math at Bar Ilan Students tion that she has learned in the move- University and takes math and science ment. As a counselor of fourth graders, courses at Tel Aviv University. -

Art and Art of Design Учебное Пособие Для Студентов 2-Го Курса Факультета Прикладных Искусств

Министерство образования Российской Федерации Амурский государственный университет Филологический факультет С. И. Милишкевич ART AND ART OF DESIGN Учебное пособие для студентов 2-го курса факультета прикладных искусств. Благовещенск 2002 1 Печатается по решению редакционно-издательского совета филологического факультета Амурского государственного университета Милишкевич С.И. Art and Art of Design. Учебное пособие. Амурский гос. Ун-т, Благовещенск: 2002. Пособие предназначено для практических занятий по английскому языку студентов неязыковых факультетов, изучающих дизайн. Учебные материалы и публицистические статьи подобраны на основе аутентичных источников и освещают последние достижения в области дизайна. Рецензенты: С.В.Андросова, ст. преподаватель кафедры ин. Языков №1 АмГУ; Е.Б.Лебедева, доцент кафедры фнглийской филологии БГПУ, канд. Филологических наук. 2 ART GALLERIES I. Learn the vocabulary: 1) be famous for -быть известным, славиться 2) hordes of pigeons -стаи голубей 3) purchase of -покупка 4) representative -представитель 5) admission -допущение, вход 6) to maintain -поддерживать 7) bequest -дар, наследство 8) celebrity -известность, знаменитость 9) merchant -торговец 10) reign -правление, царствование I. Read and translate the text .Retell the text (use the conversational phrases) LONDON ART GALLERIES On the north side, of Trafalgar Square, famous for its monument to Admiral Nelson ("Nelson's Column"), its fountains and its hordes of pigeons, there stands a long, low building in classic style. This is the National Gallery, which contains Britain's best-known collection of pictures. The collection was begun in 1824, with the purchase of thirty-eight pictures that included Hogarth's satirical "Marriage a la Mode" series, and Titian's "Venus and Adonis". The National Gallery is rich in paintings by Italian masters, such as Raphael, Correggio, and Veronese, and it contains pictures representative of all European schools of art such as works by Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, Murillo, El Greco, and nineteenth century French masters. -

Israeli & International Art Jerusalem 16 April 2009

ISRAELI & INTERNATIONAL ART JERUSALEM 16 APRIL 2009 SPECIAL PESACH AUCTION ISRAELI AND INTERNATIONAL ART KING DAVID HOTEL JERUSALEM THURSDAY, 16 APRIL 2009 9:00 P.M. 1 בס”ד Auction Preview MATSART GALLERY, 21 King David St., Jerusalem April 2 -16 : Sun.-Thu. (including Hol-Hamoed) 11 am - 10 pm Fri. 11 am - 3 pm Sat. and Holidays 9.30 pm - 12 am Wed. April 8 (Erev Pesach) by appointment only Thu. April 16, 11 am - 2 pm Private viewing is available by appointment Online auction on : www.artfact.com Online Catalogue : www.artonline.co.il Auction 111, 16 April 2009 9:00 pm King David Hotel, Jerusalem. Special preview of selected lots Auction 112 (June 2009) on view in the gallery.(See highlights on p. 106 -113) ימי תצוגה גלריה מצארט, דוד המלך 21 ירושלים 16-2 אפריל. ראשון - חמישי ׁׂׂ)כולל חול המועד( 11:00 - 22:00 שישי 11:00 - 15:00, שבת ומוצאי חג 21:30 - 24:00 רביעי, 6 אפריל )ערב פסח( לפי תיאום מראש. חמישי, 16 אפריל 11:00 - 14:00 המכירה גם באתר : www.artfact.co.il הקטלוג און-ליין בכתובת: www.artonline.co.il מכירה 111 16 באפריל 2009, 21:00, מלון המלך דוד, ירושלים מבחר פריטים ממכירה 112 )יוני 2009( יוצגו בגלריה בימי התצוגה המקדימה )ראה יצירות נבחרות בעמ’ 113-106( 3 מנהל ובעלים Director and Owner לוסיאן קריאף Lucien Krief מנכ”ל Executive Director אורי רוזנבך Uri Rosenbach [email protected] [email protected] מומחים Specialists אורן מגדל Oren Migdal מומחה לאמנות ישראלית Expert Israeli Art [email protected] [email protected] לוסיאן קריאף Lucien Krief מומחה לאסכולת פריז Expert Ecole de Paris [email protected] [email protected] שירות לקוחות Client Relations אורי רוזנבך Uri Rosenbach ברברה אפלבאום Barbara Apelbaum [email protected] [email protected] כספים Client Accounts סטלה קוסטה Stella Costa [email protected] [email protected] לוגיסטיקה ומשלוחים Logistics and Shipping רייזי גודווין Reizy Goodwin [email protected] [email protected] MATSART AUCTIONEERS AND APPRAISERS 21 King David St. -

JERUZALÉM — Věčný Zdroj Umělecké Inspirace Jerusalem — Eternal Source of Artistic Inspiration 2

JERUZALÉM — věčný zdroj umělecké inspirace Jerusalem — Eternal Source of Artistic Inspiration 2. česko-izraelské kolokvium / 2nd Czech-Israeli Colloquium Praha / Prague, 5 / 9 / 2017 Jerusalem’s Share in Building the New Prague Bianca Kühnel (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) In the lecture the part played by Jerusalem and its loca sancta buildings in the construction of the New Prague by Emperor Charles IV will be emphasized. The presentation is mainly based on two architectural monuments, the All Saints Chapel in the Royal Palace and the Wenceslas Chapel in the S. Vitus Cathedral, following the ways in which both echo essential Jerusalem traditions. The Return to Zion – Views of Jerusalem in Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts from Bohemia Sara Offenberg (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beersheva) The notion of the return to Zion is manifested throughout Jewish history both in texts and images. The hopes for eschatological redemption and the rebuilding of the Temple are apparent in Jewish art from the late antique and up to the modern period. At times the hopes are expressed mostly in the saying of “Next year in Jerusalem” at the end of the Passover Haggadah, and the text is usually accompanied by an image of Jerusalem. The city is designed by the imagination of the patron and the illuminator of the manuscript and thus looks like a medieval or early modern European urban space. In this paper I shall examine this notion in some Hebrew illuminated manuscripts produced in Bohemia. Prague and Jerusalem – The Holy Sepulchre in Kryštof Harant‘s Travels (1598) Orit Ramon (Open University of Israel) Kryštof Harant, a Czech pilgrim who visited Jerusalem in 1598, published his travel log in Czech by 1608.