Results of 42 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys from the Global Trachoma Mapping Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Map (PDF | 4.45

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - PUNJAB ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! K.P. ! ! ! ! ! ! Murree ! Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Hasan Abdal Tehsil ! Attock Tehsil ! Kotli Sattian Tehsil ! Taxila Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Attock ! ! ! ! Jand Tehsil ! Kahuta ! Fateh Jang Tehsil Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi ! ! Pindi Gheb Tehsil ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R ! ! ! ! Gujar Khan Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohawa ! Tehsil ! ! ! A F G H A N I S T A N Chakwal Chakwal ! ! ! Tehsil Sarai Alamgir Tehsil ! ! Tala Gang Tehsil Jhelum Tehsil ! Isakhel Tehsil ! Jhelum ! ! ! Choa Saidan Shah Tehsil Kharian Tehsil Gujrat Mianwali Tehsil Mianwali Gujrat Tehsil Pind Dadan Khan Tehsil Sialkot Tehsil Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Malakwal Tehsil Phalia Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Sialkot Daska Tehsil Khushab Piplan Tehsil Tehsil Wazirabad Tehsil Pasrur Tehsil Narowal Shakargarh Tehsil Shahpur Tehsil Khushab Gujranwala Bhalwal Hafizabad Tehsil Gujranwala Tehsil Tehsil Narowal Tehsil Sargodha Kamoke Tehsil Kalur Kot Tehsil Sargodha Tehsil Hafizabad Nowshera Virkan Tehsil Pindi Bhattian Tehsil Noorpur Sahiwal Tehsil Tehsil Darya Khan Tehsil Sillanwali Tehsil Ferozewala Tehsil Safdarabad Tehsil Sheikhupura Tehsil Chiniot -

Dimension and Composition of Plant Life in Tehsil Takht-E-Nasrati, District Karak, Khyber Pakhtunkhawa, Pakistan Musharaf Khan D

DIMENSION AND COMPOSITION OF PLANT LIFE IN TEHSIL TAKHT-E-NASRATI, DISTRICT KARAK, KHYBER PAKHTUNKHAWA, PAKISTAN MUSHARAF KHAN DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR 2012 i Dedication I dedicated this work to my whole family members and teachers with great love and gratitude ii In the Name of Allah The Most Compassionate The Most Merciful iii UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR PESHAWAR DIMENSION AND COMPOSITION OF PLANT LIFE IN TEHSIL TAKHT-E-NASRATI, DISTRICT KARAK, KHYBER PAKHTUN KHAWA, PAKISTAN A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Botany By Musharaf Khan Graduate Study Committee: 1. Prof. Dr. Farrukh Hussain, (Supervisor) 2. Prof. Dr. Syed Zahir Shah, (Member) 3. Prof. Dr. Muhammed Seed, (Member) 4. Prof. Dr. Siraj-ud-Din, (Member) 5. Madam Mussarat Jabeen, (Member) iv CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL This Dissertation, entitled “DIMENSION AND COMPOSITION OF PLANT LIFE IN TEHSIL TAKHT-E-NASRATI, DISTRICT KARAK, KHYBER PAKHTUN KHAWA, PAKISTAN.” submitted by Musharaf Khan is hereby approved and recommended as partial fulfillment for the award of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Botany. ______________________________ (External Examiner) Prof. Dr. Mufakhirah Jan Durrani Chairperson, Department of Biology Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad _____________________________ (Supervisor) Prof. Dr. Farrukh Hussain Research Supervisor, Department of Botany, University of Peshawar. Dated: ………………………2013 v PUBLICATION OPTION I hereby reserve the rights of publication, including right to reproduce this thesis in any form for a period of 5 years form the date of submission Musharaf Khan vi Acknowledgements This thesis would never been accomplished without the courage, strength and hope given by Almighty Allah! The most merciful, the most beneficent, who makes impossible to possible. -

Mansehra 1 Kunhar Christian Hospital, P

Valid X-ray License Holder Sr. Facility Mansehra 1 Kunhar Christian Hospital, P. O. Garhi Habibullah, Mansehra 2 Ghulam Jelani X-ray c/o Hamid Clinic, Naeem Super Market, Kaghan Road, Balakot, Mansehra 3 Fauji Foundation Hospital, Mansehra, Mansehra 4 Al-Madina Medical Store, Near Eid Gah, Gari Habib Ullah, Balakot, Mansehra 5 Gul Health Centre, Near Battal Civil Hospital, Mansehra 6 Dar-us-Shifa X-ray, Near Madina CNG, College Doraha, Mansehra 7 Naseem Surgical Centre, Upper Channie, Mansehra 8 Qazi X-ray, Opp. King Abdullah Teaching Hospital, Mansehra 9 Shifa X-ray & Ultrasound Centre, Jan Market Near King Abdullah Hospital, Mansehra 10 Zia Hospital, Shergarh Road, Ugi, Mansehra 11 New Al-Mufti Pharmacy, Chattar Plain, Mansehra 12 Qureshi Medical Centre, Ansar Plaza, Mohalla Bara Dari, Shinkiari, Mansehra 13 Ali Medical Centre, Battgram Road, Oghi, Mansehra 14 Al-Ahsan Hospital, Battal Road, Oghi, Mansehra 15 Irum Hospital, Sher Garh Road, Bilal Market, Oghi, Mansehra 16 Faisal Surgical & General Hospital, Fakhar Plaza Toheed Road, Oghi, Mansehra 17 Mansehra CT-Scan, Near King Abdullah Teaching Hospital Abbottabad Road, Mansehra 18 Maryam Clinical Lab., Al-Quraish Market, Oghi, Mansehra 19 Azam Medical Centre, Near Old Pul Garlat, Balakot, Mansehra 20 China Health Centre, Mohallah Jabri Near Circuit House, Mansehra 21 Bilal X-ray, Daud Plaza Near Chinar Masjid, Baffa, Mansehra 22 Khan Jee Surgical Hospital & Maternity Home, Bajna Road, Shinkiari, Mansehra 23 Mansehra Poly Clinic & Surgical Centre, Abbottabad Road, Mansehra 24 Hazara Digital X-ray, Opposite King Abdullah Teaching Hospital, Mansehra 25 Islamabad X-ray, Faisal Plaza Near DHQ Hospital, Mansehra 26 Moon X-ray, Shahrah-e-Raisham Faraz Market Opposite NBP Shinkiari Tehsil Baffa, Mansehra 27 Waleed X-ray, Near King Abdullah Hospital, Mansehra 28 Dr. -

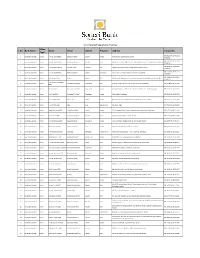

S. No. Bank Name Office Type* Name Tehsil District Province

List of Selected Operational Branches Office S. No. Bank Name Name Tehsil District Province Address License No. Type* BRL-20115 dt: 19.02.2013 1 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Lahore-0001 Lahore City Tehsil Lahore Punjab 87, Shahrah-E-Quaid-E-Azam, Lahore (Duplicate) Plot No: Sr-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al-Rahim Tower, I.I. Chundrigar Road, BRL-20114 dt: 19.02.2013 2 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Karachi-0002 Karachi South District Karachi Sindh Karachi (Duplicate) BRL-20116 dt: 19.02.2013 3 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Peshawar Peshawar Tehsil Peshawar KPK Property No: Ca/457/3/2/87, Saddar Road, Peshawar Cantt., (Duplicate) BRL-20117 dt: 19.02.2013 4 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Quetta-0004 Quetta City Tehsil Quetta Balochistan Ground Floor, Al-Shams Hotel, M.A. Jinnah Road, Quetta. (Duplicate) BRL-17606 dt: 03.03.2009 5 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Mirpur Mirpur Mirpur AJK Plot No: 35/A, Munshi Sher Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, New Mirpur Town, Mirpur (Ak) (Duplicate) Main Branch, Hyderabad.- 6 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Hyderabad City Taluka Hyderabad Sindh Shop No: 6, 7 & 8, Plot No: 475, Dr. Ziauddin Road, Hyderabad BRL-13188 dt: 04.04.1993 0006 7 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Guj-0007 Gujranwala City Tehsil Gujranwala Punjab Khewat & Khatooni: 78 Khasra No: 393 Near Din Plaza G. T. Road Gujranwala BRL-13192 dt: 14.07.1993 8 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Fsd-0008 Faisalabad City Tehsil Faisalabad Punjab Chiniot Bazar, Faisalabad BRL-13196 dt: 30.09.1993 9 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Sie Br. -

KPK-PDHQ) (219)Result for the Post of Male Warder (BPS - 05) Zone 5 PAKISTAN TESTING SERVICE MERIT LIST MALE (ZONE-5

KPK PRISONS DEPARTMENT (KPK-PDHQ) (219)Result for the post of Male Warder (BPS - 05) Zone 5 PAKISTAN TESTING SERVICE MERIT LIST MALE (ZONE-5) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Higher Total Obtained Marks of Matric Matric Experience Interview Grand Sr # Name Father Name Contact # District Address DOB Height Chest Runnning Higher Qualification Qualification Screening Screening Column Division Marks Marks Marks Total Marks Marks Marks 13+14+17 1 Sayyed Faisal Shah Zaffer Shah 03464404474 Mansehra Village Brat P/o Jinkiari Tehsil And Distt: Mansehra Feb 28 1991 5x9 39-40 pass 1st Division Graduation 70 8 100 52 130 4 134 2 Wajid Bashir Muhammad Bashir 03435876662 Abbottabad Moh Batta Kari Vill Nagribala Po Kala Bagh Nov 10 1990 5x7 34-35 Pass 1st Division Intermediate/HSSC 70 6 100 51 127 6 133 Dharmang Dhodial Argushai Po Dhodial D/T 3 Hassan Sufiyan Muhammad Sufiyan 03175575636 Mansehra Jan 13 1997 5x11 37-39 Pass 1st Division Intermediate/HSSC 70 6 100 53 129 4 133 Mansehra Village Chittian P/O Qalanderabad Tehsil And Distric 4 Bilal Khan Muhammad Younis 03109326326 Abbottabad Jan 15 1992 5x11 34-36 Pass 1st Division Graduation 70 8 100 47 125 5 130 Abbottabad H No 653/2 St No 5 Mohallah Farooq E Azam Kunj 5 Faisal Pervaiz Muhammad Pervaiz 03479730496 Abbottabad Jun 5 1992 5x7 34-36 Pass 1st Division Graduation 70 8 100 46 124 6 130 Qadeem 6 Sami Ullah Khan Abdul Hanan Khan 03145089747 Abbottabad Mohallah Khizer Zai Mirpur Abbottabad Oct 1 1989 5x8 39-40 Pass 2nd Division Masters and Above 53 12 100 58 123 6 129 7 Hamid -

X-Ray Facilities with License Valid Upto 30-06-2020

X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name of Facility Address of Facility District Mansehra Ghulam Jelani X-ray Naeem Super Market, Kaghan Road, Balakot, District 158. c/o Hamid Clinic Mansehra Al-Habib Hospital Shergarh Road, Ugi, District Mansehra 159. Qureshi Medical Ansar Plaza, Mohalla Bara Dari, Shinkiari, District 160. Centre Mansehra Khan Jee Surgical Hospital & Bajna Road, Shinkiari, District Mansehra 161. Maternity Home Al-Madina Medical Near Eid Gah, Gari Habib Ullah, Balakot, District 162. Store Mansehra Kunhar Christian P. O. Garhi Habibullah, Mansehra 163. Hospital Fauji Foundation Mansehra, Mansehra 164. Hospital Gul Health Centre Near Battal Civil Hospital, Mansehra 165. Naseem Surgical Upper Channie, Mansehra 166. Centre Qazi X-ray Opposite King Abdullah Teaching Hospital, Mansehra 167. Shifa X-ray & Jan Market Near King Abdullah Hospital, Mansehra 168. Ultrasound Centre Ali Medical Centre Battgram Road, Oghi, Mansehra 169. Irum Hospital Sher Garh Road, Bilal Market, Oghi, Mansehra 170. Near King Abdullah Teaching Hospital Abbottabad Road, Mansehra CT-Scan 171. Mansehra X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name of Facility Address of Facility Azam Medical Near Old Pul Garlat, Balakot, Mansehra 172. Centre China Health Centre Mohallah Jabri Near Circuit House, Mansehra 173. Hazara Digital X-ray Opposite King Abdullah Teaching Hospital, Mansehra 174. Islamabad X-ray Faisal Plaza Near DHQ Hospital, Mansehra 175. Shahrah-e-Raisham Faraz Market Opposite NBP Shinkiari Moon X-ray 176. Tehsil Baffa, Mansehra Advance Digital X- Garhi Habibullah, Mansehra 177. ray Al-Mir Medical Sheikh Tariq Road, Oghi, Tehsil Oghi, Mansehra 178. -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Desertification Dynamics and Its Control

DESERTIFICATION DYNAMICS AND ITS CONTROL MECHANISMS IN SEMIARID AREAS OF PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF DISTRICT KARAK PAKISTAN IFFAT TABASSUM INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY, URBAN & REGIONAL PLANNING, UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR, PAKISTAN 2011 DEDICATED TO: My Parents who had the dream for my highest possible level of education, My Husband and Children who rendered great deal of time And to the People of Karak APPROVAL SHEET This research thesis, titled “Desertification Dynamics and its Control Mechanisms in Semiarid Areas of Pakistan: A Case Study of District Karak”, submitted by Ms Iffat Tabassum, under the supervision of Dr Mohammad Aslam Khan, HEC Professor, Institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar, KPK, (Pakistan) for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography is hereby approved. External Examiner Supervisor (Prof. Dr. M. Aslam Khan) Internal Examiner ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express my sincere and deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Mohammad Aslam Khan, HEC Professor, Institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar, for his valuable advices, encouragement and guidance. Specially, I owe a big thanks to Dr. Fazlur Rahman, Associate Professor, Institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, for his continued help, critical review of research and valuable inputs. I would also like to acknowledge the positive attitude and support of Prof. Dr. Amir Khan, Director, and other faculty members, institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar enabling me in achieving my goal. I have no words to place on record my deep sense of gratitude to my teacher and colleague Prof. Dr. Mahamood-ul-Hasan, Institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar for his ever encouraging and motivating attitude, support and priceless affection. -

S. No. Bank Name Office Type* Name Tehsil District Province Address

List of Selected Operational Branches Office S. No. Bank Name Name Tehsil District Province Address License No. Type* BRL-20115 dt: 19.02.2013 1 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Lahore-0001 Lahore City Tehsil Lahore Punjab 87, Shahrah-E-Quaid-E-Azam, Lahore (Duplicate) BRL-20114 dt: 19.02.2013 2 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Karachi-0002 Karachi South District Karachi Sindh Plot No: Sr-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al-Rahim Tower, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi (Duplicate) BRL-20116 dt: 19.02.2013 3 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Peshawar Peshawar Tehsil Peshawar KPK Property No: Ca/457/3/2/87, Saddar Road, Peshawar Cantt., (Duplicate) BRL-20117 dt: 19.02.2013 4 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Quetta-0004 Quetta City Tehsil Quetta Balochistan Ground Floor, Al-Shams Hotel, M.A. Jinnah Road, Quetta. (Duplicate) BRL-17606 dt: 03.03.2009 5 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Mirpur Mirpur Mirpur AJK Plot No: 35/A, Munshi Sher Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, New Mirpur Town, Mirpur (Ak) (Duplicate) Main Branch, Hyderabad.- 6 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Hyderabad City Taluka Hyderabad Sindh Shop No: 6, 7 & 8, Plot No: 475, Dr. Ziauddin Road, Hyderabad BRL-13188 dt: 04.04.1993 0006 7 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Guj-0007 Gujranwala City Tehsil Gujranwala Punjab Khewat & Khatooni: 78 Khasra No: 393 Near Din Plaza G. T. Road Gujranwala BRL-13192 dt: 14.07.1993 8 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Fsd-0008 Faisalabad City Tehsil Faisalabad Punjab Chiniot Bazar, Faisalabad BRL-13196 dt: 30.09.1993 9 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Sie Br. -

Ethnobotanical Assessment of Plant Resources of Banda Daud Shah, District Karak, Pakistan

Murad et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2013, 9:77 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/9/1/77 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Ethnobotanical assessment of plant resources of Banda Daud Shah, District Karak, Pakistan Waheed Murad1*, Azizullah Azizullah1, Muhammad Adnan1, Akash Tariq1, Kalim Ullah Khan1, Saqib Waheed1 and Ashfaq Ahmad2 Abstract Background: The Indigenous knowledge of plants is scientifically and culturally very significant. This paper elucidates the empirical findings of an ethnobotanical survey of Banda Daud Shah, District Karak, Pakistan. Methods: Data collection was carried out from October 2011 to September 2012. Total twelve survey trips were made, three in each season. About 100 respondents were interviewed; most of them were aged people between 60–70 years. Interviews were conducted using structured questionnaire composed of variety of questions regarding ethnomedicinal uses of plants of the study area. Direct matrix ranking (DMR), informant citations and market survey of multipurpose plants were also carried out. Results: The local community was using 58 plant species belonging to 52 genera and 34 families for different purposes. A total of 25 plant species were herbs followed by 18 shrubs. Leaf (45%) was the most commonly used plant part followed by the whole plants (23%). In total, 40 plant species were medicinally used to treat variety of diseases, of which highest number of species being used for gastro-intestinal problems (19 spp.), expectorant (3 spp.) and antipyretic (3 spp.). Beside medicinal values, 25 species were used for fuel and 18 for fodder purposes. Informant consensus showed that gastrointestinal and respiratory infections were ranked highest (FIC = 0.75) among all ailments. -

Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis Along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab

p !( !( 23 August 2010 !( FL-2010-000141-PAK S p a t i o - Te m p o r a l F!( lo o d A n a l y s i s a l o n g t h e I n d u s R i v e r, S i n d h , P u n j a b , K P K a n d B a l o c h i s t a n P r o v i n c e s , P a k i s t a n p Version 1.0 !( This map shows daily variation in flo!(od water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindph, Punjab, Balochistan and KPK Index map CHINA p Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 17 to August 21, 2010. Resolution : 250m Legend 0 25 50 100 AFGHANISTAN !( Image date : August 18-22, 2010 Result show that the flood extent isq® continously increasing during the last 5 days as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil p Source : NASA Pre-Flood River Line (2009) Kilometres of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. In the Punjab provinces flood has q® Airport p Pre-flood Image : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) !( partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Ti!(bba, Faizpur, Isanwali, Mulana)as. Over 1000 villages !( ® Resolution : 250m Flood Water extent (Aug 18) p and 100 towns were identified as severly affepcted by flood waters and vanalysis was performed using geospatial database ® Heliport !( Image date : September 19, 2009 !( v !( Flood Water extent (Aug 19) ! received from University of Georgia, google earth and GIS data of NIMA (USGS).