Workshop As Network: a Case Study from Mughal South Asia Yael Rice Amherst College, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mughal Paintings of Hunt with Their Aristocracy

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Research Article Open Access Mughal paintings of hunt with their aristocracy Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2019 Mughal emperor from Babur to Dara Shikoh there was a long period of animal hunting. Ashraful Kabir The founder of Mughal dynasty emperor Babur (1526-1530) killed one-horned Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, rhinoceros and wild ass. Then Akbar (1556-1605) in his period, he hunted wild ass Nilphamari, Bangladesh and tiger. He trained not less than 1000 Cheetah for other animal hunting especially bovid animals. Emperor Jahangir (1606-1627) killed total 17167 animals in his period. Correspondence: Ashraful Kabir, Department of Biology, He killed 1672 Antelope-Deer-Mountain Goats, 889 Bluebulls, 86 Lions, 64 Rhinos, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Nilphamari, Bangladesh, 10348 Pigeons, 3473 Crows, and 10 Crocodiles. Shahjahan (1627-1658) who lived 74 Email years and Dara Shikoh (1657-1658) only killed Bluebull and Nur Jahan killed a tiger only. After study, the Mughal paintings there were Butterfly, Fish, Bird, and Mammal. Received: December 30, 2018 | Published: February 22, 2019 Out of 34 animal paintings, birds and mammals were each 16. In Mughal pastime there were some renowned artists who involved with these paintings. Abdus Samad, Mir Sayid Ali, Basawan, Lal, Miskin, Kesu Das, Daswanth, Govardhan, Mushfiq, Kamal, Fazl, Dalchand, Hindu community and some Mughal females all were habituated to draw paintings. In observed animals, 12 were found in hunting section (Rhino, Wild Ass, Tiger, Cheetah, Antelope, Spotted Deer, Mountain Goat, Bluebull, Lion, Pigeon, Crow, Crocodile), 35 in paintings (Butterfly, Fish, Falcon, Pigeon, Crane, Peacock, Fowl, Dodo, Duck, Bustard, Turkey, Parrot, Kingfisher, Finch, Oriole, Hornbill, Partridge, Vulture, Elephant, Lion, Cow, Horse, Squirrel, Jackal, Cheetah, Spotted Deer, Zebra, Buffalo, Bengal Tiger, Camel, Goat, Sheep, Antelope, Rabbit, Oryx) and 6 in aristocracy (Elephant, Horse, Cheetah, Falcon, Peacock, Parrot. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Role of Bengali Women in the Freedom Movement Abstract

Heteroglossia: A Multidisciplinary Research Journal June 2016 | Vol. 01 | No. 01 Role of Bengali Women in the Freedom Movement Kasturi Roy Chatterjee1 Abstract In India women is always affected by the lack of opportunities and facilities. This is due to innate discrimination prevalent within the society for years. Thus when the role of Bengali women in the freedom movement is considered one faces a lot of difficulty, as because the women whatever their role were never highlighted. But in recent years however it is being pointed out that Bengali women not only participated in the freedom movement but had played an active role in it. KeyWords: Swadeshi, Boycott, catalysts, Patriarchy, Civil Disobidience, Satyagraha, Quit India. 1 Assistant Professor in History, Sundarban Mahavidyalaya, Kakdwip, South 24 Parganas, Pin-743347 49 Heteroglossia: A Multidisciplinary Research Journal June 2016 | Vol. 01 | No. 01 Introduction: In attempting to analyse the role of Bengali women in the Indian Freedom Struggle, one faces a series of problem is at the very outset. There are very few comprehensive studies on women’s participation in the freedom movement. In my paper I will try to bring forward a complete picture of Bengali women’s active role in the politics of protest: Bengal from 1905-1947, which is so far being discussed in different phases. In this way we can explain that how the women from time to time had strengthened the nationalist movement not only in the way it is shaped for them but once they participated they had mobilized the movement in their own way. Nature of Participatation in the Various Movements: A general idea for quite a long time had circulated regarding women’s participation that it is male dictated. -

Miskina, Sarwan and Bhura, C1590-95 Akabarnama; Mines Exploding During the Siege of Chitor, (Mughal)

Miskina, Sarwan and Bhura, c1590-95 Akabarnama; Mines exploding during the siege of Chitor, (Mughal) Key facts: Artists: Composition by Miskina, colours and details painted by Sarwan and Bhura. Date: circa 1590-95 Medium: opaque watercolour and gold on paper Dimensions: 33 x 18.8 cm Source: this belongs to a presentation copy of the Akbarnama, the history of the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar (1542-1605). The Persian text of this copy has 116 paintings done by Akbar’s artists. Location: Victoria and Albert Museum, London (IS.2:66-1896 and IS.2:67-1896) 1. ART HISTORICAL TERMS AND CONCEPTS Subject matter: The four-month siege to capture the fort of Chitor began in October 1567. It was a key part of Akbar’s campaign against the Hindu ruler of the province of Mewar in Rajasthan, who had refused to make friendly alliances with the emperor through marriage, unlike his Rajput neighbours. The fort was seen as impregnable, and a Mughal victory here would deter future resistance. In this painting, Mughal sappers prepare covered paths and lay mines to protect the advancing army. Akbar directs their work. He is identifiable by the feather in his turban: this is an emblem of royalty, as is the flywhisk held by the attendant behind him. The text explains that the placing of the mines had been done against his advice. These exploded when the invading Mughal army rode over them, and some of Akbar’s best generals were blown up. Composition: The scene is shown in a stylised, not realistic, manner. -

Unit 17 Architecture and Painting*

Architecture and Painting UANIT 17 RCHITECTURE AND PAINTING* Structure 17.0 Objectives 17.1 Introduction 17.2 Architecture under the Delhi Sultanate 17.2.1 New Structural Forms 17.2.2 Stylistic Evolution 17.2.3 Public Buildings and Public Works 17.3 Mughal Architecture 17.3.1 Beginning of Mughal Architecture 17.3.2 Interregunum: The Sur Architecture 17.3.3 Architecture under Akbar 17.3.4 Architecture under Jahangir and Shah Jahan 17.3.5 The Final Phase 17.4 Paintings under the Delhi Sultanate 17.4.1 Literary Evidence for Murals 17.4.2 The Quranic Calligraphy 17.4.3 Manuscript Illustation 17.5 Mughal Paintings 17.5.1 Antecedents: Paintings in the Fifteenth Century 17.5.2 Painting under Early Mughals 17.5.3 Evolution of the Mughal School under Akbar 17.5.4 Developments and Jahangir and Shahjahan 17.5.5 The Final Phase 17.5.6 European Impact on Mughal Painting 17.6 Summary 17.7 Keywords 17.8 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 17.9 Suggested Readings 17.10 Instructional Video Recommendations 17.0 OBJECTIVES After going through this Unit, you should be able to: • distinguish between the pre-Islamic and Indo-Islamic styles of architecture, • identify major phases of architectural development during the period, • understand the traditions of painting prevalent in the Delhi Sultanate, • learn new structural forms and techniques of Mughal architecture, and • describe the main elements of Mughal painting. * Prof. Ravindra Kumar, School of Social Sciences, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi 357 Religion and Culture 17.1 INTRODUCTION Art and architecture are true manifestations of the culture of a period as they reflect the ethos and thought of a society. -

Chapter-I Historical Growth of Barasat Town

CHAPTER-I HISTORICAL GROWTH OF BARASAT TOWN INTRODUCTION: 'God made !the country and man made the town' - so says a proverb. Towns are created out of the necessities created by man also. For administrative reasons, for trade and commerce, and for many other obvious reasons, towns/cities emerge. Sometimes there are accidents of history (e.g. Calcutta), sometimes there are planning behind (e.g. Kalyani at Nadia District, West Bengal, Durgapur at Barddhaman District, West Bengal). The present investigation centres around a small township, which grew out of a tiny hamlet into a district town with all the characteristics associated with the process of urbanisation. The tiny hamlet expanded, attracted people from all around and developed into an administrative centre. Advantages of natural growth are no substitute for meticulous planning for tackling with the attendant problem of urbanisation. 1.1 PRE BRITISH PERIOD: The term 'Barasat' means 'Avenue'. Both sides of the road were planted with trees, Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of Bengal (1774-84), planted trees on both sides of the road. Pandit Haraprasad Shastri, a noted lndologist, was of the view that the name 'Barasat originated from the concept that on both sides of the road planted trees were in abundance. Other evidences are not lacking which prove that its history extends to the middle ages. Twelve members of the family of Jagat Sett, the banker of the Nawab of Bengal, lived here. Settpukur and other villages after their names are still there. Another Sett, Ramchandra, a descendant of Jagat Sett, dug out a tank near the Jessore Road to please Hastings. -

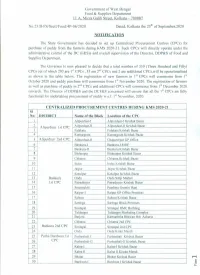

Notification on CPC.Pdf

Government of West Bengal Food & Supplies Department 11 A, Mirza Galib Street, Kolkata - 700087 No.2318-FS/Sectt/Food/4P-06/2020 Dated, Kolkata the zs" of September,2020 NOTIFICATION The State Government has decided to set up Centralized Procurement Centres (CPCs) for purchase of paddy from the farmers during KMS 2020-21. Such CPCs will directly operate under the administrative control of the DC (F&S)s and overall supervision of the Director, DDP&S of Food and Supplies Department. The Governor is now pleased to decide that a total number of 350 (Three Hundred and Fifty) nd CPCs out of which 293 are 1st CPCs ,55 are 2 CPCs and 2 are additional CPCs,will be operationalised as shown in the table below. The registration of new farmers in 1st CPCs will commence from 1sI October 2020 and paddy purchase will commence from 1st November 2020. The registration of farmers nd as well as purchase of paddy in 2 CPCs and additional CPCs will commence from 1st December 2020 onwards. The Director of DDP&S and the DCF&S concerned will ensure that all the 1st CPCs are fully functional for undertaking procurement of paddy w.e.f. 1st November, 2020. CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT CENTRES DURING KMS 2020-21 SI No: DISTRICT Name ofthe Block Location of the CPC f--- 1 Alipurduar-I Alipurduar-I Krishak Bazar 2 Alipurduar-II Alipurduar-II Krishak Bazar f--- Alipurduar 1st CPC - 3 Falakata Falakata Krishak Bazar 4 Kurnarzram Kumarzram Krishak Bazar 5 Alipurduar 2nd Cf'C Alipurduar-Il Chaporerpar GP Office - 6 Bankura-l Bankura-I RlDF f--- 7 Bankura-II Bankura Krishak Bazar I--- 8 Bishnupur Bishnupur Krishak Bazar I--- 9 Chhatna Chhatna Krishak Bazar 10 - Indus Indus Krishak Bazar ..». -

Non-Western Art History the Art of India 3

Non-Western Art History The Mughal Empire 1526 - 1707 The Art of India 3 End End 1 Art of India 3 2 Art of India 3 The Mughal Empire Established by Babur, a Muslim from Central Asia, in 1526 with the help of the rulers of Persia (modern Iran) Expanded by his grandson, Akbar (r. 1556-1605), who conquered northern and central India and laid the real foundation for the empire The Mughals, during most of their dominance, were known for strong central government and tolerance of all religions Portrait of Akbar, The Mughals grew very wealthy from trade with Europeans, the by Manohar, Ottoman Empire (Turks) and along the Silk Road 16th century, Hermitage Museum The empire expanded into part of southern India under Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), but declined after 1707 Source: The Art of the Mughals, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art End End 3 Art of India 3 4 Art of India 3 Akbar Hears a Petition, by Manohar, c. 1604, H: 10 inches, India, Freer & Sackler Galleries Akbar Hears a Petition, by Manohar, c. 1604, H: 10 inches, India, Freer & Sackler Galleries End End 5 Art of India 3 6 Art of India 3 1 Basic Beliefs of Islam Monotheistic - a belief in only one God, Allah, who is omnipotent. The overall purpose of humanity is to serve Allah, to worship him alone and to construct a moral lifestyle The Koran or Qu’ran is the holy book of Islam, the written revelation from Allah to the prophet Muhammad in the 6th century. -

Behind the Veil:An Analytical Study of Political Domination of Mughal Women Dr

11 Behind The Veil:An Analytical study of political Domination of Mughal women Dr. Rukhsana Iftikhar * Abstract In fifteen and sixteen centuries Indian women were usually banished from public or political activity due to the patriarchal structure of Indian society. But it was evident through non government arenas that women managed the state affairs like male sovereigns. This paper explores the construction of bourgeois ideology as an alternate voice with in patriarchy, the inscription of subaltern female body as a metonymic text of conspiracy and treachery. The narratives suggested the complicity between public and private subaltern conduct and inclination – the only difference in the case of harem or Zannaha, being a great degree of oppression and feminine self –censure. The gradual discarding of the veil (in the case of Razia Sultana and Nur Jahan in Middle Ages it was equivalents to a great achievement in harem of Eastern society). Although a little part, a pinch of salt in flour but this political interest of Mughal women indicates the start of destroying the patriarchy imposed distinction of public and private upon which western proto feminism constructed itself. Mughal rule in India had blessed with many brilliant and important aspects that still are shining in the history. They left great personalities that strengthen the history of Hindustan as compare to the histories of other nations. In these great personalities there is a class who indirectly or sometime directly influenced the Mughal politics. This class is related to the Mughal Harem. The ladies of Royalty enjoyed an exalted position in the Mughal court and politics. -

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who Was the Successor of Jahangir

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who was the successor of Jahangir? Who was the last most power full ruler in the Mughal dynasty? What was the administrative policy of Aurangzeb? The main causes of Downfall of Mughal Empire. Shah Jahan was the successor of Jahangir and became emperor of Delhi in 1627. He followed the policy of his ancestor and campaigns continued in the Deccan under his supervision. The Afghan noble Khan Jahan Lodi rebelled and was defeated. The campaigns were launched against Ahmadnagar, The Bundelas were defeated and Orchha seized. He also launched campaigns to seize Balkh from the Uzbegs was successful and Qandhar was lost to the Safavids. In 1632Ahmadnagar was finally annexed and the Bijapur forces sued for peace. Shah Jahan commissioned the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal marks the apex of the Mughal Empire; it symbolizes stability, power and confidence. The building is a mausoleum built by Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz and it has come to symbolize the love between two people. Jahan's selection of white marble and the overall concept and design of the mausoleum give the building great power and majesty. Shah Jahan brought together fresh ideas in the creation of the Taj. Many of the skilled craftsmen involved in the construction were drawn from the empire. Many also came from other parts of the Islamic world - calligraphers from Shiraz, finial makers from Samrkand, and stone and flower cutters from Bukhara. By Jahan's period the capital had moved to the Red Fort in Delhi. Shah Jahan had these lines inscribed there: "If there is Paradise on earth, it is here, it is here." Paradise it may have been, but it was a pricey paradise. -

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings

An example of this last category could be “Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings” (fig. 10).7 At the center is Jahangir enthroned, his physiognomy in the strict profile known from many paintings and even — quite unusually — from gold coins. His head is the only one to be surrounded by a halo, and he is slight- ly larger than the other figures, a phenomenon that is called hierarchical or significance perspective. He is extending a book to Shaykh Husayn of the Chishti order, which played an essential role in the life of the imperial family. Below is an imaginary depiction of an Ottoman sultan, presumably inspired by a Euro- pean model, and in front is a portrait of King James I, copied directly from a contemporary painting brought to India by the English ambassador, Thom- as Roe. At the lower left-hand corner, Bichitr placed a portrait of himself, a custom that became common in the ensuing years, though often with these artist portraits more modestly included in the imperial of the same event from the time of Bahadur Shah (r. made at the Muslim courts could be harrowing in albums as margin decorations.8 A painting like this 1707–1712).10 their realism if the patron wished, and similar hor- one can be viewed as a kind of sophisticated propa- Jahangir, whose character is also familiar from rifying depictions from battlefields are also found in ganda, and this was true to an even greater extent in his autobiography, Jahangirnama or Tuzuk-i Jahangiri, some of the historical manuscripts of the period (e.g.