Wheatley Limestone and Its Business the Location of Wheatley Conferred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drawings by J. B. Malchair in Corpus Christi College

Drawings by J. B. Malchair In Corpus Christi College By H. MINN HERE have recently come to light in Corpus Christi College library T eleven volumes of drawings by J. B. Malchair and his pupils, drawn between the years 1765-1790.1 Malchair was a music and drawing master, and resided in Broad Street. A full account of all that is known of him will be found in an article by Paul Oppe in the Burlington Maga<:ine for August, 194-3. This collection appears to have been made by John Griffith, Warden of Wadham College, 1871-81, and consists of 339 water-colour, indian ink, and pencil sketches; of these no less than 138 are views in and about the City and drawn by Malchair himself. A full list of all the drawings depicting Oxford or neighbouring places will be found in the Appendix; the remainder of the drawings depict places outside the range of Oxonunsia. Malchair's drawings of the City are very valuable records, and it is satisfactory to note that most of his known drawings are now to be found in Oxford; for, in addition to this collection, there is a fine collection in the Ashmolean Museum and a few other drawings are among the Bodleian topographical collection; but there were others of great interest in existence in 1862 (see Proceedings of the Oxford Architectural and Historical Society, new series, I, 14-8), and it is to be hoped that these, if still in existence, may some day find a home in Oxford. The value of Malchair's drawings is much enhanced by his habit of writing on the back the subject, the year, day of the month and often the hour at which the drawing was made. -

2-25 May 2020 Scenes and Murals Wallpaper AMAZING ART in WONDERFUL PLACES ACROSS OXFORDSHIRE

2-25 May 2020 Scenes and Murals Wallpaper AMAZING ART IN WONDERFUL PLACES ACROSS OXFORDSHIRE. All free to enter. Designers Guild is proud to support Oxfordshire Artweeks Available throughout Oxfordshire including The Curtain Shop 01865 553405 Anne Haimes Interiors 01491 411424 Stella Mannering & Company 01993 870599 Griffi n Interiors 01235 847135 Lucy Harrison Fabric | Wallpaper | Paint | Furniture | Accessories Interiors www.artweeks.org 07791 248339 Fairfax Interiors designersguild.com FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE 01608 685301 & ARTIST DIRECTORY Fresh Works Paintings by Elaine Kazimierzcuk 7 - 30 May 2020 The North Wall, South Parade, Oxford OX2 7JN St Edward’s School is the principal sponsor of The North Wall’s innovative public programme of theatre, 4 Oxfordshire Artweeks music, art exhibitions,www.artweeks.org dance and talks.1 THANKS WELCOME Oxfordshire Artweeks 2020 Artweeks is a not-for-profit organisation and relies upon the generous Welcome to the 38th Oxfordshire Artweeks festival during support of many people to whom we’re most grateful as we bring this which you can see, for free, amazing art in hundreds of celebration of the visual arts to you. These include: from Oxfordshire Artweeks 2020 Oxfordshire from wonderful places, in artists’ homes and studios, along village trails and city streets, in galleries and gardens Patrons: Will Gompertz, Mark Haddon, Janina Ramirez across the county. It is your chance, whether a seasoned Artweeks 2020 to Oxfordshire art enthusiast or an interested newcomer, to enjoy art in Board members: Anna Dillon, Caroline Harben, Kate Hipkiss, Wendy a relaxed way, to meet the makers and see their creative Newhofer, Hannah Newton (Chair), Sue Side, Jane Strother and Robin talent in action. -

Scheduled Monuments in Oxfordshire Eclited by D

Scheduled Monuments in Oxfordshire Eclited by D. B. HARDEN HE Council for British Archaeology has recently issued the second eclition T of its J1emorandum on the Ancient Monuments Acts of 1913, 1931 and 1953.' This pamphlet explains in brief terms the provisions of the Acts and the machinery instituted by the Ministry of Works for operating them. It con tains also a list of local correspondents of the Mjnistry of Works, county by county, through whom reports and information about ancient monuments in the counties may be forwarded to the Ancient Monuments Department of the Ministry for action by the Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments and his staff'. The information contained in the pamphlet is so important and so lucidly set out that the Committee has reacliJy acceded to a request from the Council for British Archaeology that its substance should be reprinted here. It is hoped that aJl members of the Society will make themselves familiar with the facts it provides, and be ready to keep the necessary watch on ancient monu ments in their area whether scheduled or not scheduled. Any actual or impend ing destruction or damage should be reported without delay either to the Cbief Inspector of Ancient Monuments or to the Ministry's Local Correspondent in the county in which the monument lies. (A list of the correspondents for Oxfordshire and neighbouring counties is given in Appendix I.) Special watch should, of course, be kept on monuments already scheduled, which are, for the very reason that they are scheduled, to be presumed to be amongst the most important ancient remains in the clistrict. -

Traffic Sensitive Streets – Briefing Sheet

Traffic Sensitive Streets – Briefing Sheet Introduction Oxfordshire County Council has a legal duty to coordinate road works across the county, including those undertaken by utility companies. As part of this duty we can designate certain streets as ‘traffic-sensitive’, which means on these roads we can better regulate the flow of traffic by managing when works happen. For example, no road works in the centre of Henley-on-Thames during the Regatta. Sensitive streets designation is not aimed at prohibiting or limiting options for necessary road works to be undertaken. Instead it is designed to open-up necessary discussions with relevant parties to decide when would be the best time to carry out works. Criteria For a street to be considered as traffic sensitive it must meet at least one of the following criteria as set out in the table below: Traffic sensitive street criteria A The street is one on which at any time, the county council estimates traffic flow to be greater than 500 vehicles per hour per lane of carriageway, excluding bus or cycle lanes B The street is a single carriageway two-way road, the carriageway of which is less than 6.5 metres wide, having a total traffic flow of not less than 600 vehicles per hour C The street falls within a congestion charges area D Traffic flow contains more than 25% heavy commercial vehicles E The street carries in both directions more than eight buses per hour F The street is designated for pre-salting by the county council as part of its programme of winter maintenance G The street is within 100 metres of a critical signalised junction, gyratory or roundabout system H The street, or that part of a street, has a pedestrian flow rate at any time of at least 1300 persons per hour per metre width of footway I The street is on a tourist route or within an area where international, national, or significant major local events take place. -

RAVE Walk 10 June April Oxfordshire Way Stage 2

Oxfordshire Way Stage 2 Linear Walk Sunday 10th June 2018, Christmas Common to Title Tiddington Walk Christmas Common – Pyrton – Adwell – Tetsworth – Rycote - Tiddington Map Sheets Map Sheet 1:25,000 OS Explorer Series Sheet 171 – Chiltern Hills West Sheet 180 – Oxford, Witney & Woodstock Notes The walk is linear from Christmas Common to Tiddington. For this walk we will all meet at the end point and transfer to the start in a few of the cars, leaving at least one to enable the drivers to be ferried back to the start. Anybody not keen on acting as a taxi please let me know. This is a lovely walk passing through the villages of Pyrton and Tetsworth and hamlets of Adwell and Rycote - famous for its Chapel. A shorter walk can be completed at Adwell, at approximately 6.5 to 7.0 miles, and we can leave a car there. Walkers to meet at the Fox & Goat PH in Tiddington OX9 2LH Start time 09.45 am for a 10.00 am start. Start and Finish Start - Public Car Park Christmas Common near Watlington GR 702934 Postcode OX49 5HS – Parking is free. Finish - The Fox & Goat PH in Tiddington OX9 2LH Difficulty Leisurely 11.5 miles Leader Neil Foster Mobile 07712 459783 Email [email protected] Waypoints Waypoints: Start – From Christmas Common NT car park we follow the path straight down the ridge to Pyrton. We then zigzag our way to Adwell, past an old chapel. After crossing under the M40 to Tetsworth, we ascend Lobbersdown Hill and continue past the Oxford Golf course before reaching Rycote and its Chapel. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1591

1591 1591 At RICHMOND PALACE, Surrey. Jan 1,Fri New Year gifts; play, by the Queen’s Men.T Jan 1: Esther Inglis, under the name Esther Langlois, dedicated to the Queen: ‘Discours de la Foy’, written at Edinburgh. Dedication in French, with French and Latin verses to the Queen. Esther (c.1570-1624), a French refugee settled in Scotland, was a noted calligrapher and used various different scripts. She presented several works to the Queen. Her portrait, 1595, and a self- portrait, 1602, are in Elizabeth I & her People, ed. Tarnya Cooper, 178-179. January 1-March: Sir John Norris was special Ambassador to the Low Countries. Jan 3,Sun play, by the Queen’s Men.T Court news. Jan 4, Coldharbour [London], Thomas Kerry to the Earl of Shrewsbury: ‘This Christmas...Sir Michael Blount was knighted, without any fellows’. Lieutenant of the Tower. [LPL 3200/104]. Jan 5: Stationers entered: ‘A rare and due commendation of the singular virtues and government of the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, with the happy and blessed state of England, and how God hath blessed her Highness, from time to time’. Jan 6,Wed play, by the Queen’s Men. For ‘setting up of the organs’ at Richmond John Chappington was paid £13.2s8d.T Jan 10,Sun new appointment: Dr Julius Caesar, Judge of the Admiralty, ‘was sworn one of the Masters of Requests Extraordinary’.APC Jan 13: Funeral, St Peter and St Paul Church, Sheffield, of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (died 18 Nov 1590). Sheffield Burgesses ‘Paid to the Coroner for the fee of three persons that were slain with the fall of two trees that were burned down at my Lord’s funeral, the 13th of January’, 8s. -

Minutes of the Great Haseley Parish Council Held on Monday 13 July 2015 at 7.30 Pm in the Village Hall

MINUTES OF THE GREAT HASELEY PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY 13 JULY 2015 AT 7.30 PM IN THE VILLAGE HALL Present : D Simcox (Chairman); J Andrews; H Harvey; K Sentance; A Sheppard. J Simcox, Clerk; S Harrod (County and District Councillor) and one member of the public. 15/44 Public Discussion P Woodrow presented the Parish Council with a set of accounts for the Village Hall and asked if the donation that the Parish Council made annually to the Village Hall could be increased to £2,000 from £1,500 as the amount had not been increased for about 10 years. He explained that the Village Hall Committee were concerned that the money given by the Parish Council now no longer covered the basic running costs of the village hall and it was now a necessity to earn other income in order to keep it going. The Parish Council said that the budget for this year showed that they had allocated £1,500 but that they were all in agreement that for the next financial year this amount should be increased to £2,000. The Parish Council thanked the Village Hall Committee for all their hard work of keeping the Hall in good condition and wished them success in their new work being undertaken on the hall. Discussion took place regarding websites and it was agreed that H Harvey would talk to P Lee to try to find a way forward so that all interested groups could have access to a website. 15/45 Apologies for absence were received from D Mann; E Spencer 15/46 There were no declarations of interest in items on the agenda. -

Women in the Building Trades, 1600‒1850: A

Richard Hewlings, ‘Women in the building trades, 1600–1850: A preliminary list’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. X, 2000, pp. 70–83 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2000 WOMEN IN THE BUILDING TRADES, ‒ : A PRELIMINARY LIST RICHARD HEWLINGS ary Slade was not unique, but she was unusual rate books, for instance, and the relationship between Mnevertheless. Out of a sample of some , these women and male building tradesmen of the people engaged in the building industry between same name could be determined rather than merely and , no more than were women, speculated on, as here. Since most of these women’s approximately %. names come from accounts, that source would also These women are listed below, but the limitations furnish information about rates of pay and profit, of the sample have to be noted. It is, first, a random and, occasionally, about employees, materials and sample, , names recorded in the course of transport. Insurance company records would provide researching other subjects – particular buildings, not information about stock and premises. The list particular issues nor particular persons. There are may therefore provide a starting point for a proper inevitable distortions in favour of certain times and study of the subject; such a study would not only certain places, not to mention the distortions caused illuminate women’s history, but the history of the by absence of primary evidence. The first half of the building trade as well. seventeenth century, for instance, is thinly represented, Thirdly, the building trade is here defined as the so are Scotland, Wales and large parts of southern provision of immovables, so providers of furniture, and western England. -

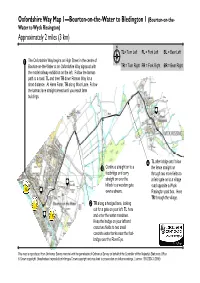

Oxfordshire Way Maps

Oxfordshire Way Map 1—Bourton-on-the-Water to Bledington 1 (Bourton-on-the- Water to Wyck Rissington) Approximately 2 miles (3 km) TL= Turn Left FL = Fork Left BL = Bear Left The Oxfordshire Way begins on High Street in the centre of Bourton-on-the-Water at an Oxfordshire Way signpost with TR = Turn Right FR = Fork Right BR = Bear Right the model railway exhibition on the left. Follow the tarmac path to a road. TL and then TR down Roman Way for a short distance. At Harm Farm, TR along Moor Lane. Follow the tarmac lane straight ahead until you reach farm buildings. C TL after bridge and follow Continue straight on to a the fence straight on footbridge and carry through two more fields to D straight on over the a field-gate on to a village hillock to a wooden gate road opposite a Wyck A over a stream. Rissington post box. Here TR through the village. TR along a hedged lane, looking out for a gate on your left. TL here B and enter the water meadows. Keep the hedge on your left and cross two fields to two small concrete water tanks near the foot- bridge over the River Eye. This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence: 100023343 (2008) Oxfordshire Way Map 2 —Bourton-on-the-Water to Bledington 2 (Wyck Rissington to Gawcombe House) Approximately 2 miles (3 km) Follow road through the village to a small stone church. -

HIGHWAY INTO YESTERDAY by Magnus Magnusson a Piece of Road Is a Cross-Section of the Road Has Not Only Seen and Absorbed .History

HIGHWAY INTO YESTERDAY by Magnus Magnusson A piece of road is a cross-section of The road has not only seen and absorbed .history. And, like history, every stretch is all the history of the place it serves, it has different, flavoured by local circum- also helped to shape it. Take just one stances. Excavate a section of ancient road stretch of highway: part of the A40 and you can read a profile of dusty between London and Oxford. From centuries stretching into the remote past. Wheatley to the 73 HIGHWAY INTO YESTERDAY Islip turn-off is a mile-long stretch of dual farmhouse. carriageway, completed in 1964 at a cost No one can be sure precisely how old the of about £435,000. road is. The first hunter-gatherers made It was designed as a microcosm of all paths through the virgin forests 10,000 roads: for experimental purposes 75 years ago, discarding primitive flint knives methods of constructing a base were and scrapers at their campsites. They were used—not that the millions of motorists followed by farmers who cleared the who pound along it notice. woods for ploughland and pasture, and Although its line has changed with the created settled communities some 6000 passing of time, this route has for centuries years ago—the beginnings of civilised been a principal artery of English history. society as we know it. With their arrival, Royalty has ridden it, armies marched it; the random hunting paths were replaced by post horses have galloped it, waggons and more enduring patterns of lanes and by- carriages rutted it; wayfarers have ways. -

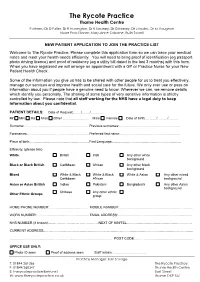

New-Patient-Registration-Pack-1.Pdf

The Rycote Practice Thame Health Centre Partners: Dr D Faller, Dr R Harrington, Dr K Keaney, Dr D Keeley, Dr J Makris, Dr M Vaughan Nurse Practitioner: Mary-Anne Osborne, Ruth Tossell NEW PATIENT APPLICATION TO JOIN THE PRACTICE LIST Welcome to The Rycote Practice. Please complete this application form so we can trace your medical notes and meet your health needs efficiently. You will need to bring proof of identification (eg passport, photo driving licence) and proof of residency (eg a utility bill dated in the last 3 months) with this form. When you have registered we will arrange an appointment with a GP or Practice Nurse for your New Patient Health Check. Some of the information you give us has to be shared with other people for us to treat you effectively, manage our services and improve health and social care for the future. We only ever use or pass on information about you if people have a genuine need to know. Wherever we can, we remove details which identify you personally. The sharing of some types of very sensitive information is strictly controlled by law. Please note that all staff working for the NHS have a legal duty to keep information about you confidential. PATIENT DETAILS: Date of Request:….…/.……/….……. Mr Mrs Ms Miss Other …………………… Male Female Date of birth:… ……/………/……… Surname:..……………………………………………….. Previous surnames:………………………………………………. Forenames:..………………………………….. …………Preferred first name:……………………………………………… Place of birth:……………………………………………..First Language:……………………………………………………. Ethnicity: (please tick) White British Irish Any other white background Black or Black British Caribbean African Any other black background Mixed White & Black White & Black White & Asian Any other mixed Caribbean African background Asian or Asian British Indian Pakistani Bangladeshi Any other Asian background Chinese Any other ethnic Other Ethnic Groups group HOME PHONE NUMBER: ……………………………. -

Thame Cycling Around 2014.Cdr

10 rides between 12 and 21 miles through Cycling from Thame attractive villages and beautiful countryside key surrounding historic Thame Sustrans National Eythrope Cycle Route 57 (NCR 57) Upper Winchendon Park 0 1 2 3 4km Bridleways (cycleways) Brill Footpaths 0 1 2miles Public houses Boarstall Wood River Thame Horton-cum- Stone This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the M40 Little Nether Winchendon Hartwell permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Studley London Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown copyright. B401 Oakley 1 A418 Oakley Wood 21st Century Thame cannot accept responsibility for any errors that may have occurred in producing this map. April 2014 Chilton Upton Sedrup Shabbington Wood Gibraltar Cuddington Haddenham: Church and Village pond Chearsley Dinton Bishopstone Easington Westlington Route 10 Distance 30.0km (18.6 miles) A418 Thame - Shabbington - Ickford - Worminghall - Shabbington Wood - Oakley - Worminghall - Thame Townsend Ford Marsh Leaving Thame at point F Head west and join the A418 to North Haddenham Weston then minor road to Shabbington and through to Worminghall (following NCR 57). From Worminghall there is a Worminghall Long Crendon circular ride around Shabbington Wood through Oakley. Return to B401 M40 Thame via Shabbington and North Weston. Point 1 F St Tiggywinkles Aston Wildlife Hospital Sandford Church End Kimble Ickford Wick Golf Driving Range Clanking Route 9 Distance 31.8km (19.7 miles) Shabbington Little G Little Thame - Shabbington - Ickford - Ickford Kimble Brill Windmill A418 Worminghall - Oakley - Brill - Chilton - Waterperry River Thame Kingsey A4129 Long Crendon - Shabbington - Thame THAME Smokey A4129 Row Leaving Thame at point F Head west and join the Route 1 Meadle Draycot A Owlswick A418 to North Weston then minor road to Distance 33.5km (20.8 miles) F Great B4009 Shabbington (following NCR 57).