Agder2010 Keynote Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anna Halprin's Dance-Events

AUTONOMY AS A TEMPORARY COLLECTIVE EXPERIENCE: ANNA HALPRIN’S DANCE-EVENTS, DEWEYAN AESTHETICS, AND THE EMERGENCE OF DIALOGICAL ART IN THE SIXTIES by Tusa Shea BA, University of Victoria, 2002 MA, University of Victoria, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in Art Tusa Shea, 2012 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-88455-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-88455-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas Collection of Jack Kerouac Material, Circa 1900-2005

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Kerouac, Jack, 1922-1969. Title: John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Extent: 2 linear feet (4 boxes) and 1 oversized papers box (OP) Abstract: Material collected by John Sampas relating to Jack Kerouac and including correspondence, photographs, and manuscripts. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Jack Kerouac papers, New York Public Library Related Materials in This Repository Jack Kerouac collection and Jack and Stella Sampas Kerouac papers Source Purchase, 2015 Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Citation [after identification of item(s)], John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Philip Pearlstein

PHILIP PEARLSTEIN 1924 Born in Pittsburgh, PA on May 24 1942-49 B.F.A. from Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh, PA 1955 M.A. from New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, New York, NY 1959-63 Instructor, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY 1962-63 Visiting Critic, Yale University, New Haven, CT 1963-88 Professor of Fine Art, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, NY 1988 Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, NY 2003-06 President, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY The artist lives and works in New York City. Solo Exhibitions 2018 Philip Pearlstein, Today, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, May 10 – June 17 Philip Pearlstein, Paintings 1990- 2017, Saatchi Gallery, London, United Kingdom, January 17 – April 29 2017 Facing You, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, May 5 – June 30 Philip Pearlstein: Seventy –Five Years of Painting, Susquehanna Museum of Art, Harrisburg, PA, February 11 – May 21 2016 G.I. Philip Pearlstein, World War II Captured on Paper, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, September 14 – October 15 2015-16 Pearlstein | Warhol | Cantor: From Carnegie Tech to New YorK, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, Dec. 3 – March 5, 2016 2015 Pearlstein | Warhol | Cantor : From Pittsburgh to New YorK, Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA May 30- September 6 2014 Philip Pearlstein, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, May 8 – July 27 Pearlstein at 90, Russell Bowman Art Advisory, Chicago, IL, April 4 – May 31 Philip Pearlstein: Six Paintings, Six Decades, National Academy of Art, New York, NY, Feb. 27 – May 11 Philip Pearlstein – Just The Facts, 50 Years of Looking and Drawing and Painting, Curated by Robert Storr, New York Studio School, New York, NY, January 16 – February 22 2013 Philip Pearlstein’s People, Places, Things, Museum of Fine Arts, St. -

What Are You If Not Beat? – an Individual, Nothing

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “What are you if not beat? – An individual, nothing. They say to be beat is to be nothing.”1 Individual and Collective Identity in the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Sarah Posman fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Sarah Devos May 2014 1 From “Variations on a Generation” by Gregory Corso 0 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Posman for keeping me motivated and for providing sources, instructive feedback and commentaries. In addition, I would like to thank my readers Lore, Mathieu and my dad for their helpful additions and my library companions and friends for their driving force. Lastly, I thank my two loving brothers and especially my dad for supporting me financially and emotionally these last four years. 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1. Ginsberg, Beat Generation and Community. ............................................................ 7 Internal Friction and Self-Promotion ...................................................................................... 7 Beat ......................................................................................................................................... 8 ‘Generation’ & Collective Identity ......................................................................................... 9 Ambivalence in Group Formation -

This Is Not a Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2015 This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Moore, Walter Gainor, "This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections" (2015). Open Access Dissertations. 1421. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1421 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 1/15/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Walter Gainor Moore Entitled THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Lance A. Duerfahrd Chair Daniel Morris P. Ryan Schneider Rachel L. Einwohner To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Lance A. Duerfahrd Approved by: Aryvon Fouche 9/19/2015 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Walter Moore In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Lance, my advisor for this dissertation, for challenging me to do better; to work better—to be a stronger student. -

National Gallery of Art Spring10 Film Washington, DC Landover, MD 20785

4th Street and Mailing address: Pennsylvania Avenue NW 2000B South Club Drive NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART SPRING10 FILM Washington, DC Landover, MD 20785 A JOURNEY STILL VOICES, THROUGH INNER LIVES: MOVING SPANISH CATALUNYA: THE JOURNALS COMPOSITIONS: EXPERIMENTAL POETRY OF OF ALAIN ASPECTS OF FILM PLACE CAVALIER CHOPIN BEAT MEMORIES de Barcelona), cover calendar page calendar International), page four page three page two The Savage Eye Arrebato The Savage Eye L’arbre deL’arbre les cireres Battle of Wills Tríptico elemental de España SPRING10 details from (Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona) (Photofest) (Photofest) (InformAction and Philippe Lavalette) Philippe (InformAction and The Savage Eye (Photofest) (Centre de Cultura Contemporania , Thérèse (Photofest), Irène (Pyramid Monuments: Matta-Clark, Graham, Smithson Redmond Entwistle in person Saturday June 19 at 2:00 Film Events A clever and amusing critique of three minimalists, Monuments portrays a problem that emerges in the work of Robert Smithson, Gordon Matta- Clark, and Dan Graham, as each artist retraces his relationship to New Figaros Hochzeit (The Marriage of Figaro) Jersey. “An alle gory for the effects that globalization has had on society Introduction by Harry Silverstein and landscape” — Rotterdam Film Festival. (Redmond Entwistle, 2009, Saturday April 17 at 1:00 16 mm, 30 minutes) The postwar German DEFA studio (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft) Manhattan in 16 mm produced a series of popular black-and-white opera films in the late 1940s Saturday June 19 at 3:30 at their Potsdam-Babelsberg facility. Mozart’s Figaros Hochzeit, the first of these, featured wonderfully showy sets and costumes. (Georg Wildhagen, A sequence of documentary and experimental shorts, filmed over the past 1949, 35 mm, German with subtitles, 109 minutes) Presented in association twenty years in the now rare 16 mm gauge, observes, lionizes, and languishes with Washington National Opera. -

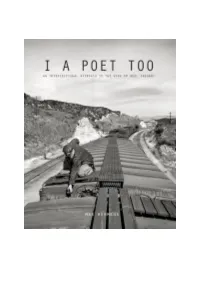

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

The Portable Beat Reader Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PORTABLE BEAT READER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ann Charters | 688 pages | 07 Oct 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780142437537 | English | London, United Kingdom The Portable Beat Reader PDF Book What We Like Waterproof design is lightweight Glare-free screen. Nov 21, Dayla rated it it was amazing. See all 6 brand new listings. Night mode automatically tints the screen amber for midnight reading. The author did an excellent job of reviewing each writer - their history, works, etc - before each section. Diane DiPrima Dinners and Nightmares excerpt 5. Animal Farm and by George Orwell and A. Get BOOK. Quick Links Amazon. Although in retrospect, my knowledge was hardly rich with understanding, even though I'd read some Burroughs, knew of Kerouac and On the Road , Ginsberg and Howl. And last but not least, Family Library links your Amazon account to that of your relatives to let you conveniently share books. Again, no need to sit down and read the whole thing. She guides you through all the sections of the Beats Generation: Kerouac's group in New York, the San Francisco Poets, and the other groups that were inspired by the work these groups produced. Members Reviews Popularity Average rating Mentions 1, 7 10, 4. First off, Amazon has included a brand-new front light that allows you to read in the dark, something that was previously only available on the more expensive Kindle Paperwhite. But Part 5 was my joy! E-readers are also a great option for kids to explore. Status Charters, Ann Editor primary author all editions confirmed Baraka, Amiri Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Bremser, Ray Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Bukowski, Charles Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Burroughs, William S. -

“But Cantos Oughta Sing”: Jack Kerouac's Mexico City

The Albatross is pleased to feature the graduating essay of Jack Derricourt which won the 2011 English Honours Essay Scholarship. “But Cantos Oughta Sing”: Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues and the British-American Poetic Tradition Jack Derricourt During the post-war era of the 1950s, American poets searched for a new direction. The Cold War was rapidly reshaping the culture of the United States, including its literature, stimulating a variety of poets to rein- terpret the historical lineage of poetic expression in the English language. Allen Grossman, a poet and critic who undertook such a reshaping in the fifties, turns to the figure of Caedmon from the Venerable Bede’s early eighth century Ecclesiastical History of the English People to seek out the roots of British-American poets. For Grossman, Caedmon represents an important starting point within the long tradition of English-language poetry: Bede’s visionary layman crafts a non-human narrative—a form of truth witnessed beyond the confines of social institutions, or transcend- ent truth—and makes it intelligible through the formation of conventional symbols (Grossman 7). The product of this poetic endeavour is the song. The figure of Caedmon also appears in the writings of Robert Duncan as a model of poetic transference: I cannot make it happen or want it to happen; it wells up in me as if I were a point of break-thru for an “I” that may be any person in the cast of a play, that may like the angel speaking to Caedmon to command “Sing me some thing.” When that “I” is lost, when the voice of the poem is lost, the matter of the poem, the intense infor- mation of the content, no longer comes to me, then I know I have to wait until that voice returns. -

America Singing Loud: Shifting Representations of American National

AMERICA SINGING LOUD: SHIFTING REPRESENTATIONS OF AMERICAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ALLEN GINSBERG AND WALT WHITMAN Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English Literature By Eliza K. Waggoner Dayton, Ohio May 2012 AMERICA SINGING LOUD: SHIFTING REPRESENTATIONS OF AMERICAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ALLEN GINSBERG AND WALT WHITMAN Name: Waggoner, Eliza K. APPROVED BY: ____________________________________________________ Albino Carrillo, MFA Committee Chair ____________________________________________________ Tereza Szeghi, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________________________________ James Boehnlein, Ph. D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT AMERICA SINGING LOUD: SHIFTING REPRESENTATIONS OF AMERICAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ALLEN GINSBERG AND WALT WHITMAN Name: Waggoner, Eliza K. University of Dayton Advisor: Mr. Albino Carrillo Much work has been done to study the writings of Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg. Existing scholarship on these two poets aligns them in various ways (radicalism, form, prophecy, etc.), but most extensively through their homosexuality. While a vast majority of the scholarship produced on these writers falls under queer theory, none acknowledges their connection through the theme of my research—American identity. Ideas of Americanism, its representation, and what it means to be an American are issues that span both Whitman and Ginsberg's work. The way these issues are addressed and reconciled by Ginsberg is vastly different from how Whitman interacts with the subject: a significant departure due to the nature of their relationship. Ginsberg has cited Whitman as an influence on his work, and other scholars have commented on the appearance of this influence. The clear evidence of connection makes their different handling of similar subject matter a doorway into deeper analysis of the interworking of these two iconic American writers.