Comics and Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Modeling and Matrix Training to Teach Pretend Play in Children with Autism

Video Modeling and Matrix Training 1 Video Modeling and Matrix Training to Teach Pretend Play in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder A Thesis Presented by Lauren M. Dannenberg In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In the field of Applied Behavior Analysis Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts August 2010 Video Modeling and Matrix Training 2 NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Bouvé College of Health Sciences Graduate School Thesis Title: A replication of Video Modeling and Matrix Training to teach pretend play in children with autism. Author: Lauren M. Dannenberg Masters of Science in Applied Behavior Analysis Committee members: _________________________________________________ ______________ Rebecca MacDonald Date _________________________________________________ ______________ William Ahearn Date _________________________________________________ ______________ Chata Dickson Date Video Modeling and Matrix Training 3 Video Modeling and Matrix Training to Teach Pretend Play in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Lauren Dannenberg Northeastern University Submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Applied Behavior Analysis in the Bouvé College of Health Sciences Graduate School of Northeastern University, August 2010 Video Modeling and Matrix Training 4 Acknowledgements Thanks and appreciation to Rebecca MacDonald, the research supervisor of this Master’s Thesis, for her guidance and support throughout the data collection and writing of this Thesis. Special thanks are also offered to Cara Grieco for her assistance with data collection and to Cormac MacManus for his assistance throughout the process of this project. Video Modeling and Matrix Training 5 Abstract The purpose of this study was to combine video modeling with matrix training to teach play skills in young children with autism. -

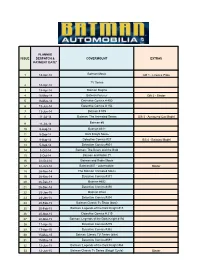

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date* Covermount

PLANNED ISSUE DESPATCH & COVERMOUNT EXTRAS PAYMENT DATE* 1 18-Apr-14 Batman Movie Gift 1 - Licence Plate TV Series 2 18-Apr-14 3 18-Apr-14 Batman Begins 4 16-May-14 Batman Forever Gift 2 - Binder 5 16-May-14 Detective Comics # 400 6 13-Jun-14 Detective Comics # 156 7 13-Jun-14 Batman # 575 8 11-Jul-14 Batman: The Animated Series Gift 3 - Armoured Car Model 9 11-Jul-14 Batman #5 10 8-Aug-14 Batman #311 11 5-Sep-14 Dark Knight Movie 12 8-Aug-14 Detective Comics #27 Gift 4 - Batwing Model 13 5-Sep-14 Detective Comics #601 14 3-Oct-14 Batman: The Brave and the Bold 15 3-Oct-14 Batman and Robin #1 16 31-Oct-14 Batman and Robin Movie 17 31-Oct-14 Batman #37 - Jokermobile Binder 18 28-Nov-14 The Batman Animated Movie 19 28-Nov-14 Detective Comics #371 20 26-Dec-14 Batman #652 21 26-Dec-14 Detective Comics #456 22 23-Jan-15 Batman #164 23 23-Jan-15 Detective Comics #394 24 20-Feb-15 Batman Classic Tv Show (boat) 25 20-Feb-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #15 26 20-Mar-15 Detective Comics # 219 27 20-Mar-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #156 28 17-Apr-15 Detective Comics #219 29 17-Apr-15 Detective Comics #362 30 15-May-15 Batman Classic TV Series (bike) 31 15-May-15 Detective Comics #591 32 12-Jun-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #64 33 12-Jun-15 Batman Classic Tv Series (Batgirl Cycle) Binder 34 10-Jul-15 Batman Arkham Asylum Video Game 35 10-Jul-15 Batman & Robin (Vol 2) #5 36 7-Aug-15 Detective Comics #667 (Subway Rocket) 37 7-Aug-15 Batman Beyond: Animated Series 38 4-Sep-15 Legends of the Dark Knight (Bike) 39 27-Nov-15 All Star Batman & Robin The Boy Wonder #1 40 4-Sep-15 The Dark Knight Rises Movie 41 2-Oct-15 Batman The Return #1 42 2-Oct-15 The New Adventures of Batman. -

Superhero Origins As a Sentence Punctuation Exercise

Superhero Origins as a Sentence Punctuation Exercise The Definition of a Comic Book Superhero A comic book super hero is a costumed fictional character having superhuman/extraordinary skills and has great concern for right over wrong. He or she lives in the present and acts to benefit all mankind over the forces of evil. Some examples of comic book superheroes include: Superman, Batman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman, and Plastic Man. Each has a characteristic costume which distinguishes them from everyday citizens. Likewise, all consistently exercise superhuman abilities for the safety and protection of society against the forces of evil. They ply their gifts in the present-contemporary environment in which they exist. The Sentence Punctuation Assignment From earliest childhood to old age, the comics have influenced reading. Whether the Sunday comic strips or editions of Disney’s works, comic book art and narratives have been a reading catalyst. Indeed, they have played a huge role in entertaining people of all ages. However, their vocabulary, sentence structure, and overall appropriateness as a reading resource is often in doubt. Though at times too “graphic” for youth or too “childish” for adults, their use as an educational resource has merit. Such is the case with the following exercise. Superheroes as a sentence punctuation learning toll. Among the most popular of comic book heroes is Superman. His origin and super-human feats have thrilled comic book readers, theater goers, and television watchers for decades. However, many other comic book superheroes exist. Select one from those superhero origin accounts which follow and compose a four paragraph superhero origin one page double-spaced narative of your selection. -

76052-1: Batman™ Classic TV Series – Batcave

76052-1: Batman™ Classic TV Series – Batcave By Jetro Pictures by Jetro and LEGO System A/S Batman is back in glorious 60s style and in a large 2526pc set that includes a total of 9 minifi gs. Is it a collectors item? A playset? Or is there too much nostalgia for either option? This review will (hopefully) give you the answer. Even though I wasn’t even around when the original Batman TV series aired in the 60s (January 1966 to March 1968), the iconic images of Batman and Robin chasing villains in loud colours, accompanied by large speech bubbles emphasising the power of their punches are still etched in my memory from the many reruns of this iconic show. As a result the 76052 Batman Classic TV Series Batcave is instantly recognisable, if only because of the classic lines of the Batmobile – they don’t make cars like that anymore. 72 Today’s Batman is a much darker knight, but even so, the colourful lines of the original TV series as represented in this set have an instant appeal, and not only those of us who saw the series on TV. I wanted to know if it was just my memories that drew me to the set (despite not being much of a super heroes fan, at least not when it comes to LEGO), so I sat down with my kids to build the set together and see what their reactions were. The instruction manual for this set is one hefty volume. On the one hand this has the important advantage that it is less likely to bend and deteriorate inside the box. -

Original BATCOPTER & BATMOBILE at 2016 Air Show

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Original BATCOPTER & BATMOBILE at 2016 Air Show Caped Crusader line-up debuts in Cleveland CLEVELAND, OH (August 3, 2016) - The 2016 Cleveland National Air Show presented by Discount Drug Mart will feature the BATCOPTER and BATMOBILE on Labor Day Weekend (Sept. 3, 4 & 5) at Burke Lakefront Airport in downtown Cleveland. Appearing for the first time in Cleveland, Batman history will be brought to life as the BATCOPTER takes to the skies and the BATMOBILE cruises the taxiway showing off its bat- gadgets including the turbine after burner. The superhero line-up will also be on display inside the Air Show grounds. Attendees will see a true piece of Americana plus meet the TV, movie and air show pilot, Captain Eugene A. Nock, A.T.P. The original BATCOPTER N3079G from the TV series Batman (1966-1968) is fully equipped with props from the show and for authenticity the instrument panel is autographed by the stars including Burt Ward “Robin”. The 1966 BATMOBILE is armed with all the crime fighting devices. Headlining this year’s show are the U.S. Navy Blue Angels. They will be joined by the U.S. Air Force’s F-22 Raptor Demonstration and F-35 Heritage Flight. The impressive line-up also includes the U.S. Army Golden Knights parachute team, world aerobatic champion Matt Chapman, Third Strike Wingwalking and more. Inside the gates, spectators will feel the heat of Shockwave Jet Truck and ground shaking pyrotechnics with a Wall of Fire. Fans can tour unique aircraft, help pack a parachute, meet a pilot and explore aviation first hand. -

On to the Batboat History !!!

The 1966 Batman TV Tribute Site - The Batboat !! Page 1 of 8 When Batman and Robin needed to sail the high seas they needed a vehicle that was fast, mobile and deadly. The Batboat was created for the 1966 Batman full length feature movie and was used in the TV series after it's movie appearance. Click For A Larger View ! When I started my research on the Batboat, I had read a few articles that suggested George Barris built the boat. I found this to be completely false ! The Batboat was the creation of Glastron Industries. The masterminds behind this incredible boat were Mel Whitley and Robert Hammond . Both of these men provided history, photos and stories about the creation of the boat and I cant thank them enough for their help !!! On to the Batboat History !!! Lets turn the Batcomputer back to 1966 shall we? http://www.1966batfan.com/batboat1.htm 7/9/2009 The 1966 Batman TV Tribute Site - The Batboat !! Page 2 of 8 We are in Austin Texas walking up to a huge factory, a hint of fiberglass scent is in the air. When we walk in we say hello to Robert Hammond, who is the president of Glastron. You decide that Glastron is no backyard operation, they have been in business for ten years and have been a leader in that new boat material, fiberglass. Click For Larger Photo ! You glance in and notice that the company just purchased a new IBM punch card computer for it's accounting department so they sure are up to date ! We walk down the hall and get introduced to Mel Whitley, he is the man responsible for bringing the Batboat to life ! So with the introductions out of the way, let us look back on how the Batboat came to be. -

Batman: Eternal: Volume 1 Free Download

BATMAN: ETERNAL: VOLUME 1 FREE DOWNLOAD Jason Fabok,Scott Snyder,Tim Seeley | 448 pages | 09 Dec 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401251734 | English | United States Batman Eternal (Volume 1) At the height the 's Batman television shows popularity, a shonen manga magazine in Japan Jun 13, Stabbing rated it liked it Shelves: dc- comicskindle-lending-enabled. When a gang war Batman: Eternal: Volume 1 out and new villains arise, it's up to the Dark Knight, Batgirl, and more A new weekly Batman series that examines the relationship between the heroes, villains, and citizens of Gotham City! The drama was mostly stemming from actual politics and difficult-to-prove crimes, giving Batman and company no clear villain to punch. The explosion is revealed to have been a Wayne Enterprises weapons cache, one of seventeen placed around the city to assist Batman Incorporated. Joker's Daughter Elsewhere, Vicki Vale follows a lead on potential gang wars in the Narrows, and, upon confronting them, is saved by Harper Row. He starts searching for the mastermind, first tracking down the Riddler and later Ra's al Ghul—the only Batman: Eternal: Volume 1 he believes who have the ability carry out such a sophisticated plan—only for both of them to convince him of their innocence, arguing that they could easily destroy a weakened Batman, but that they must Batman: Eternal: Volume 1 him at the height of his powers in order to prove their power over him. That aside, the 3. James Jr, one of my favorite DC psychos, has a small role. Batboat Batcopter Batcycle Batmobile Batplane. -

Batman 66: Volume 2 Free

FREE BATMAN 66: VOLUME 2 PDF Jonathan Case,Jeff Parker | 168 pages | 05 May 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401254612 | English | United States Batman '66 HC ( DC) comic books InDC began publication of Batman '66, which tells all-new stories set in the world of the —68 TV series. It was written by Jeff Parkerand featured cover art by Mike Allred while interior art was done by different artists each issue. PenguinJokerRiddlerCatwoman and Mr. Freeze also appear in the series. Characters who were not featured in the television series some of them created after the series ended also appeared in Batman Batman 66: Volume 2 with the Red Hood and Dr. The series was released both physically and digitally. Batman 66: Volume 2 series was cancelled inwith physical issue 30, cover-dated Februaryand digital issue In Aprilthe first five issues were compiled into the Batman '66 Batman 66: Volume 2. Additional volumes collecting the rest of the issues have since been released. In Julythe Batman arch villains attempted to take over Riverdale in the Archie meets Batman '66 mini- series. Response to the series was positive. Benjamin Bailey of IGN gave the first issue a 9. It's a blast from start to finish. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Batman '66 Cover of Batman '66 1. DC Comics. Retrieved Comic Book Resources. The Onion. Retrieved 1 November Comic Vine. Archived from the original on November 23, Writer Harlan Ellison got as far as pitching a Two-Face-themed episode before the combination of the villain's gruesome appearance and Ellison's conflicts with ABC executives killed the idea. -

Batman Game Features Matrix

Batman Game Features Matrix Main Batman pinball takes players on a feature packed adventure thru the campy world of the Dynamic Duo Attractions Featuring action video footage from the iconic TV series blended with all new animations and display effects on the LED screen and integrated into game play events Introducing the dynamic rotating Action Turntable Mini Playfield which presents the player with numerous alternating shots and targets; the interactive "Villain Vision TV Set" Action Turntable features a Batcave with spinning Batmobile Target and Nuclear Reactor shot, the Batphone, the Batcomputer and the Bat Analyzer Turntable features a physical 3 ball lock which helps players achieve an 8 ball multiball event Batman pinball game features a modern version of one of the most popular toys in the history of modern pinball, the interactive crane from Batman The Dark Knight Game is an all new layout featuring 2 crossing steel ramps with wireform returns and a variety of new shot combinations Limited Super Premium Edition Limited Edition Episode Edition Game Speech calls by Adam West (Batman) and Burt Ward (Robin) Features Production limited to 80 machines - 30 anniversary years of Stern, and 50 anniversary years of Batman Production limited to 120 Episode Editions- each game receives a unique ID plate named for one of the episodes of the show Production limited to 120 Gadget Editions- each game receives a unique ID plate named for a Bat Gadget Batman trading card by TOPPS presented in a special holder. Games get cards signed by Adam West (Batman) Certificate of authenticity signed by Gary Stern Autographed playfield featuring designer George Gomez and programmer Lyman F. -

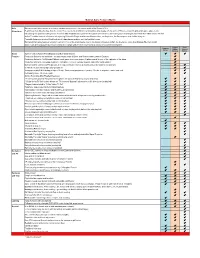

Batman by Mattel (2001 to 2012) Animated Classic Please Mark the Quantity You Have to Sell in the Column with the Red 2-Packs Arrow

Brian's Toys Batman Figures Buy List Mattel Quantity Year Item Buy List Name Line Manufacturer Wave UPC you have TOTAL Notes Released Number Price to sell Last Updated: April 14, 2017 Questions/Concerns/Other Full Name: Address: Delivery Address: W730 State Road 35 Phone: Fountain City, WI 54629 Tel: 608.687.7572 ext: 3 E-mail: How did you find us? (please fill in) Fax: 608.687.7573 Email: [email protected] Brian’s Toys will require a list of your items if you are interested in receiving a price quote on your collection. It is very Note: Buylist prices on this sheet may change after 30 days important that we have an accurate description of your items so that we can give you an accurate price quote. By Guidelines for following the below format, you will help ensure an accurate quote for your collection. As an alternative to this excel form, we have a webapp available for http://buylist.brianstoys.com/lines/Batman/toys . Selling Your Collection The buy list prices reflect items mint in their original packaging. Before we can confirm your quote, we will need to know what items you have to sell. The below list is by Batman category. STEP 1 Search for each of your items and mark the quantity you want to sell in the column with the red arrow. STEP 2 Once the list is complete, please mail, fax, or e-mail to us. If you use this form, we will confirm your quote within 1-2 business days upon receiving it. -

Batman 66 14 Review

Batman 66 14 review click here to download TweetShareShareShare. Batman '66 # “The Batrobot Takes Flight/Bat-Villains Unite” Written by Jeff Parker Illustrated by Paul Rivoche and Craig Rousseau Colored by Tony Aviña Letters by Wes Abbott. Mortality. We are all but men, mortal and finite, and even the greatest of heroes such as the Batman. Compare critic reviews for Batman '66 #14 by Jeff Parker and Paul Rivoche, published by DC Comics. Review: Batman '66 # This issue sees the return of Jeff Parker as writer. Thankfully, he turns in a story that is stronger than some of his other recent efforts. Professor Overbeck, who is becoming a major character in this series, in conjunction with Batman, has created a Bat-Robot to take some of the. Batman '66 #14 has 7 ratings and 1 review. Nicolo said: Batman and Robin are out cold, snoozing some pretty intense REM sleep. The Sandman (not the Gaima. Tom King has had fun throughout his Batman run with classic and not-so classic villains showing up and that continues here. Batman and Catwoman take down a colorful rogues gallery that would be more at home in the Batman '66 Universe and I loved it. Clock King, Magpie, Condiment King the list goes. It's time we finish out our foray into bringing current Batman villains into the world of Batman '66 and while I love the idea of bringing these villains into this world, too much too soon is never a good idea. So yeah, I hope that it continues periodically down the line . -

Aerobatic Pilot

Short FINAL NEWS FROM THE FIELD Sean D. Tucker Named Recipient of 2016 Lloyd P. Nolen Lifetime Achievement in Aviation Award erobatic pilot Sean D. Tucker has been Anamed the recipient of the Lloyd P. Nolen Life- time Achievement in Aviation Award, presented annually by the Commemorative Air Force (CAF) Wings Over Houston Airshow. “I’m honored to be recognized with an award named for Lloyd Nolen, a man who inspired us to celebrate aviation and to preserve and remember our history,” said Tucker, who flew his custom-made Oracle Chal- lenger III airplane at this year’s CAF Wings Over Houston Airshow on October 22 and 23, 2016, at Ellington Airport. The Lloyd P. Nolen Award is presented to an individual, organization, or company for lifetime achievement and promotion or advancement of another aerobatic pilot. He’s a Among Tucker’s many hon- Tucker also is very active in the aviation. Nolen, a humble and fan favorite all over the world, ors, he is an inductee of the community. He is the founder noble visionary, was a founding and we’re always honored to National Aviation Hall of Fame and president of the Califor- member and dynamic force of have him in our lineup and and the International Aviation nia-based non-profit Every the Commemorative Air Force. grateful for his help in publi- Air and Space Hall of Fame. In Kid Can Fly, which facilitates cizing our show.” 2003, Tucker was selected as transformative life experiences “Sean is most deserving of this one of the 25 Living Legends in education and aviation for award not only for what he Tucker has been flying air does in the air but also for his shows worldwide since the of Flight by the Smithsonian at-risk and underprivileged contributions to aviation and mid-1970s and has won nu- National Air and Space Mu- teenagers.