Planetary Portent 1524.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

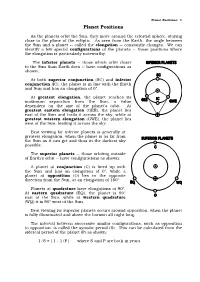

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

The Midnight Sky: Familiar Notes on the Stars and Planets, Edward Durkin, July 15, 1869 a Good Way to Start – Find North

The expression "dog days" refers to the period from July 3 through Aug. 11 when our brightest night star, SIRIUS (aka the dog star), rises in conjunction* with the sun. Conjunction, in astronomy, is defined as the apparent meeting or passing of two celestial bodies. TAAS Fabulous Fifty A program for those new to astronomy Friday Evening, July 20, 2018, 8:00 pm All TAAS and other new and not so new astronomers are welcome. What is the TAAS Fabulous 50 Program? It is a set of 4 meetings spread across a calendar year in which a beginner to astronomy learns to locate 50 of the most prominent night sky objects visible to the naked eye. These include stars, constellations, asterisms, and Messier objects. Methodology 1. Meeting dates for each season in year 2018 Winter Jan 19 Spring Apr 20 Summer Jul 20 Fall Oct 19 2. Locate the brightest and easiest to observe stars and associated constellations 3. Add new prominent constellations for each season Tonight’s Schedule 8:00 pm – We meet inside for a slide presentation overview of the Summer sky. 8:40 pm – View night sky outside The Midnight Sky: Familiar Notes on the Stars and Planets, Edward Durkin, July 15, 1869 A Good Way to Start – Find North Polaris North Star Polaris is about the 50th brightest star. It appears isolated making it easy to identify. Circumpolar Stars Polaris Horizon Line Albuquerque -- 35° N Circumpolar Stars Capella the Goat Star AS THE WORLD TURNS The Circle of Perpetual Apparition for Albuquerque Deneb 1 URSA MINOR 2 3 2 URSA MAJOR & Vega BIG DIPPER 1 3 Draco 4 Camelopardalis 6 4 Deneb 5 CASSIOPEIA 5 6 Cepheus Capella the Goat Star 2 3 1 Draco Ursa Minor Ursa Major 6 Camelopardalis 4 Cassiopeia 5 Cepheus Clock and Calendar A single map of the stars can show the places of the stars at different hours and months of the year in consequence of the earth’s two primary movements: Daily Clock The rotation of the earth on it's own axis amounts to 360 degrees in 24 hours, or 15 degrees per hour (360/24). -

Dawn Spacecraft Begins Approach to Dwarf Planet Ceres 30 December 2014, by Elizabeth Landau

Dawn spacecraft begins approach to dwarf planet Ceres 30 December 2014, by Elizabeth Landau 2012, capturing detailed images and data about that body. "Ceres is almost a complete mystery to us," said Christopher Russell, principal investigator for the Dawn mission, based at the University of California, Los Angeles. "Ceres, unlike Vesta, has no meteorites linked to it to help reveal its secrets. All we can predict with confidence is that we will be surprised." The two planetary bodies are thought to be different in a few important ways. Ceres may have formed later than Vesta, and with a cooler interior. Current evidence suggests that Vesta only retained a small This artist's concept shows NASA's Dawn spacecraft amount of water because it formed earlier, when heading toward the dwarf planet Ceres. Credit: radioactive material was more abundant, which NASA/JPL-Caltech would have produced more heat. Ceres, in contrast, has a thick ice mantle and may even have an ocean beneath its icy crust. (Phys.org)—NASA's Dawn spacecraft has entered Ceres, with an average diameter of 590 miles (950 an approach phase in which it will continue to close kilometers), is also the largest body in the asteroid in on Ceres, a Texas-sized dwarf planet never belt, the strip of solar system real estate between before visited by a spacecraft. Dawn launched in Mars and Jupiter. By comparison, Vesta has an 2007 and is scheduled to enter Ceres orbit in average diameter of 326 miles (525 kilometers), March 2015. and is the second most massive body in the belt. -

Star of Bethlehem: an Astronomical and Historical Perspective

THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM: AN ASTRONOMICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE By Susan S. Carroll The Star of Bethlehem is one of the most powerful, and enigmatic, symbols of Christianity. Second perhaps only to the Cross of the Crucifixion, the importance of its role in the story of the Nativity of the Christ child is almost on a par with the birth itself. However, the true origin of the Star of Bethlehem has baffled astronomers, historians, and theologians for the past two millennia. For the purposes of this discussion we shall consider four possibilities: That the star was a one-shot occurrence - never before seen and has not been seen since; it was placed in the sky by God to announce the birth of His Son; That the Star was added to the story of the Nativity after the fact; That the Star was a real, documentable astronomical object; That the entire New Testament is fake. If you subscribe to the first theory, then we, as astronomers, have nothing to talk about. It was a supernatural miracle that defies scientific explanation. However, many theologians insist on putting some sort of divine interpretation on Matthew s writings. By admitting that the Star was a natural phenomenon, with an actual scientific explanation, is tantamount to totally removing its heavy symbolic significance. After all, how could something so miraculous have such a mundane explanation? There is a certain amount of credence to the second theory. At the time of Jesus' birth, very few people recognized its significance. The only time the Star is mentioned at all is in the Book of Matthew. -

Essential Dignity

Essential Dignity Essential dignity is a way of evaluating the innate level of development or refinement of each planet in the chart. Planets that have a lot of essential dignity are generally stronger, show more positive effects, are better integrated into the personality, and function more freely in their domains. Some modern astrologers give little credence to the rulerships, just as they fail to regard any planet as innately malefic or benefic. In surveying the history of astrology, this is evidently a great error. The rulerships are a seminal principle in astrology, and one on which a large proportion of interpretive work was based for thousands of years before the common era. Sign Rulerships The first consideration in assessing the essential dignity of a planet is to observe whether it is in a sign that it rules. Each planet rules two signs, except the sun and moon, which rule only one each. When planets are in the signs they rule, the expression of their energy is easy and has relatively free reign. You should imagine that the planets are literal rulers of their respective signs, which constitute their kingdoms. Rulers within their own kingdoms have the benefit of their own resources to execute their desires, provide for their protection, and distribute to other regions. Rulers in foreign lands are necessarily more vulnerable and subject to interference. This will become an important operative principle when we discuss dispositorship below. Planetary rulership of the signs falls within a pattern that is often little appreciated by modern astrologers. That pattern is illustrated in the following diagram: k j l 3 3 i 4 4 a 5 5 g b 7 7 h 8 8 c 9 6 f d e The sun and moon rule Leo and Cancer respectively. -

Stellium Handbook Part

2 Donna Cunningham’s Books on the Outer Planets If you’re dealing with a stellium that contains one or more outer planets, these ebooks will help you understand their role in your chart and explore ways to change difficult patterns they represent. Since The Stellium Handbook can’t cover them in the depth they deserve, you’ll gain a greater perspective through these ebooks that devote entire chapters to the meanings of Uranus, Neptune, or Pluto in a variety of contexts. The Outer Planets and Inner Life volumes are $15 each if purchased separately, or $35 for all three—a $10 savings. To order, go to PayPal.com and tell them which books you want, Donna’s email address ([email protected]), and the amount. The ebooks arrive on separate emails. If you want them sent to an email address other than the one you used, let her know. The Outer Planets and Inner Life, V.1: The Outer Planets as Career Indicators. If your stellium has outer planets in the career houses (2nd, 6th, or 10th), or if it relates to your chosen career, this book can give you helpful insights. There’s an otherworldly element when the outer planets are career markers, a sense of serving a greater purpose in human history. Each chapter of this e-book explores one of these planets in depth. See an excerpt here. The Outer Planets and Inner Life, v.2: Outer Planet Aspects to Venus and Mars. Learn about the love lives of people who have the outer planets woven in with the primary relationship planets, Venus and Mars, or in the relationship houses—the 7th, 8th, and 5th. -

The Planets in 2006 the Distinctive Planetary Events of 2006

The Planets in 2006 The Distinctive Planetary Events of 2006..............................................................................................................2 Longitudes of the Planets ........................................................................................................................................3 Ingresses ................................................................................................................................................................3 Element, Mode and Dignity Balance.....................................................................................................................3 Table 1: 2006 Planetary Ingresses ....................................................................................................................5 Table 2: 2006 Lunar Ingresses and Void of Course Times................................................................................6 Table 3: 2006 Planetary Longitudes at a Glance..............................................................................................7 Planetary Stations ..................................................................................................................................................8 Table 4: Current Retrograde Cycles, Planet by Planet .....................................................................................8 Lunar Cycles ............................................................................................................................................................9 -

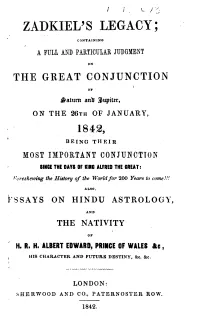

Zadkiel's Legacy; Containing a ... Judgment of the Great Conjunction Of

| # , C / 2. ZADKIEL' S LEGACY ; CoNTA in ING A FULL AND PARTICULAR JUDGMENT oN THE GREAT CONJUNCTION or $aturn ant; 3)upiter, ON THE 26TH OF JANUARY, 1842, BE ING THE IR M0ST IMPORTANT CONJUNCTION | SINGE THE DAYS OF KING ALFRED THE GREAT: Foreshewing the History of the World for 200 Years to come!!! | AL80, Fss AYs on HINDU As TRology, A.N. p. THE NATIVITY of H. R. H. ALBERT EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALEs &e, t HIS CHARACTER AND FUTURE DESTINY, &c, &c. LONDON: S HERWOOD AND CO., PATER NOSTER ROW. 1842. com PT on AND RITCHI E, PR1NTERs, Middl E - star Et, cloth - FAIR, LoN Don. - - - - - - - - . * … - - - - - - - * > z. *. -- - * • -- * * 2. - - -- - - - - - - - * - - - ~ : * - * - - - - - - - - * * * * * ***. *> - - - - - - , * * ~ : , , , * * * * * * : ... " - - -- - * * - */ " /~~ - £". * - - * - - - * 2. " - * PR EFACE. MANY generations shall pass by, many centuries roll away, and this book shall still remain a memento of the sublime powers of astral influence; for lo! I have commenced it at the moment of Mercury southing on this present first day of Sep tember, in the year of Grace one thousand eight hundred and forty, when fixed signs did occupy the angles of the heavenly scheme, the Moon and lord of the sign ascending being also in fixed signs, five planets angular, the lord of the ascendent in the ninth, or house of science, and the Moon, while ruling that house, being situate in the ascendant, in sextile to the glorious Sol, ruler of the 10th, or house of fame, and applying to a close conjunction of the bounteous and benefic Jupiter. Moreover, Mercury, on the cusp of the 10th, is in reception of the Sun, caput draconis is in the 4th, and the lord of the ascendant in trine aspect to the ruler of that house, which go verns the end of the matter. -

Communications with Mars During Periods of Solar Conjunction: Initial Study Results

IPN Progress Report 42-147 November 15, 2001 Communications with Mars During Periods of Solar Conjunction: Initial Study Results D. Morabito1 and R. Hastrup2 During the initial phase of the human exploration of Mars, a reliable commu- nications link to and from Earth will be required. The direct link can easily be maintained during most of the 780-day Earth–Mars synodic period. However, dur- ing periods in which the direct Earth–Mars link encounters increased intervening charged particles during superior solar conjunctions of Mars, the resultant eects are expected to corrupt the data signals to varying degrees. The purpose of this article is to explore possible strategies, provide recommendations, and identify op- tions for communicating over this link during periods of solar conjunctions. A sig- nicant improvement in telemetry data return can be realized by using the higher frequency 32 GHz (Ka-band), which is less susceptible to solar eects. During the era of the onset of probable human exploration of Mars, six superior conjunctions were identied from 2015 to 2026. For ve of these six conjunctions, where the sig- nal source is not occulted by the disk of the Sun, continuous communications with Mars should be achievable. Only during the superior conjunction of 2023 is the signal source at Mars expected to lie behind the disk of the Sun for about one day and within two solar radii (0.5 deg) for about three days. I. Introduction During the initial phase of the human exploration of Mars, a reliable communications link to and from Earth will be required. -

Dawn Mission to Vesta and Ceres Symbiosis Between Terrestrial Observations and Robotic Exploration

Earth Moon Planet (2007) 101:65–91 DOI 10.1007/s11038-007-9151-9 Dawn Mission to Vesta and Ceres Symbiosis between Terrestrial Observations and Robotic Exploration C. T. Russell Æ F. Capaccioni Æ A. Coradini Æ M. C. De Sanctis Æ W. C. Feldman Æ R. Jaumann Æ H. U. Keller Æ T. B. McCord Æ L. A. McFadden Æ S. Mottola Æ C. M. Pieters Æ T. H. Prettyman Æ C. A. Raymond Æ M. V. Sykes Æ D. E. Smith Æ M. T. Zuber Received: 21 August 2007 / Accepted: 22 August 2007 / Published online: 14 September 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The initial exploration of any planetary object requires a careful mission design guided by our knowledge of that object as gained by terrestrial observers. This process is very evident in the development of the Dawn mission to the minor planets 1 Ceres and 4 Vesta. This mission was designed to verify the basaltic nature of Vesta inferred both from its reflectance spectrum and from the composition of the howardite, eucrite and diogenite meteorites believed to have originated on Vesta. Hubble Space Telescope observations have determined Vesta’s size and shape, which, together with masses inferred from gravitational perturbations, have provided estimates of its density. These investigations have enabled the Dawn team to choose the appropriate instrumentation and to design its orbital operations at Vesta. Until recently Ceres has remained more of an enigma. Adaptive-optics and HST observations now have provided data from which we can begin C. T. Russell (&) IGPP & ESS, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1567, USA e-mail: [email protected] F. -

Jupiter Saturn Great Conjunction

Jupiter Saturn Great Conjunction drishtiias.com/printpdf/jupiter-saturn-great-conjunction Why in News In a rare celestial event, Jupiter and Saturn will be seen very close to each other (conjunction) on 21st December 2020, appearing like one bright star. Key Points Conjunction: If two celestial bodies visually appear close to each other from Earth, it is called a conjunction. Great Conjunction: Astronomers use the term great conjunction to describe meetings of the two biggest worlds in the solar system, Jupiter and Saturn. It happens about every 20 years. The conjunction is the result of the orbital paths of Jupiter and Saturn coming into line, as viewed from Earth. Jupiter orbits the sun about every 12 years, and Saturn about every 29 years. The conjunction will be on 21st December, 2020, also the date of the December solstice. It will be the closest alignment of Saturn and Jupiter since 1623, in terms of distance. The next time the planets will be this close is 2080. They will appear to be close together, however, they will be more than 400 million miles apart. 1/2 Jupiter: Fifth in line from the Sun, Jupiter is, by far, the largest planet in the solar system – more than twice as massive as all the other planets combined. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are called Jovian or Gas Giant Planets. These have thick atmosphere, mostly of helium and hydrogen. Jupiter’s iconic Great Red Spot is a giant storm bigger than Earth that has raged for hundreds of years. Jupiter rotates once about every 10 hours (a Jovian day), but takes about 12 Earth years to complete one orbit of the Sun (a Jovian year). -

Finder Chart for Jim's Pick of the Month December 2020 Grand

Finder Chart for Jim’s Pick of the Month December 2020 Grand Junction of Jupiter and Saturn Image via Rice University On December 21, 2020, the day of the December solstice is the great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. It will be the first Jupiter and Saturn conjunction since the year 2000 and the closest conjunction since 1623 - 14 years after Galileo made his first telescope. The closest observable Jupiter and Saturn conjunction before that was in the year 1226. At their closest in December, Jupiter and Saturn will be only 0.1 degree apart. The closest Jupiter-Saturn conjunction in 2020 will not be seen again until March 15, 2080. From Portland, after sunset at 4:30 p.m., Jupiter and Saturn conjunction will be low in the evening twilight and will set quickly, so a good clear southwestern horizon is essential. Viewed from earth, Jupiter and Saturn will be 0.1 degree apart. Jupiter will appear brightest at magnitude of -1.97, while Saturn, to the upper right, will be half the brightest at +0.63 magnitude. Far above the southern horizon is the near first quarter moon and red planet Mars. They appears to be close, yet separated 455,762,323 miles apart from each other. The planet Saturn, the sixth planet from the sun, is 1,006,711,393 miles from earth, while Jupiter, the fifth planet, is 550,949,070 miles away. Both Jupiter and Saturn will set at 6:52 p.m. towards the SW horizon. Binoculars will separate them into two objects with Saturn, the fainter of the two, lying above the mighty Jupiter.