Breaking the Age Barrier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growth Poles Program Political Economy of Social Capital

Public Disclosure Authorized GROWTH POLES PROGRAM POLITICAL ECONOMY OF SOCIAL CAPITAL Economic and Sector Work (ESW) Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM AFTP3) Competitive Industries Practice Finance and Private Sector Development (AFTFW) Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank Africa Region This image cannot currently be displayed. Public Disclosure Authorized April 2014 Copyright. 2013 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW Washington DC Telephone: 202 473 1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org Email: [email protected] All Rights Reserved The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s), and do no not necessarily reflect the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Right and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Centre, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400,fax 978-750-4470, www.copyright.com . -

Sierra Rutile Project Area 1 – Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment: Mine Closure Plan

Sierra Rutile Project Area 1 – Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment: Mine Closure Plan Report Prepared for Sierra Rutile Limited Report Number: 515234/ Mine Closure Plan Report Prepared by March 2018 SRK Consulting: Project No: 515234/Closure Page i Sierra Rutile Project Area 1 – Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment: Mine Closure Plan Sierra Rutile Limited SRK Consulting (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd 265 Oxford Rd Illovo 2196 Johannesburg South Africa e-mail: [email protected] website: www.srk.co.za Tel: +27 (0) 11 441 1111 Fax: +27 (0) 11 880 8086 SRK Project Number 515234/ Mine Closure Plan March 2018 Compiled by: Reviewed by: James Lake, Pr Sci Nat Marius Van Huyssteen, CEAPSA Principal Scientist Principal Scientist/Associate Partner Email: [email protected] Authors: Fran Lake, James Lake LAKJ/vhuy 515234_Area 1_ MCP_Rep_Final_201803 March 2018 SRK Consulting: Project No: 515234/Closure Page ii Table of Contents Disclaimer .............................................................................................................................................. v List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... vi 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of this report ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 Project overview -

The Governance of Artisanal Fisheries in the Sherbro River Area of Sierra Leone

The Governance of Artisanal Fisheries in the Sherbro River Area of Sierra Leone This project is funded by A report by The European Union Environmental Justice Foundation EXECUTIVE SUMMARY © EJF This report sets out the historic and existing governance arrangements for artisanal fishing in the Sherbro River Estuary (hereafter ‘the Estuary’), where fishing is vital to the livelihoods and food security of local communities. It uses research from 17 community visits and interviews of key stakeholders to analyse current and historic conditions at the levels of local communities, traditional authorities, local government and central government. Four key findings and recommendations are summarised below: 1. FINDING: After seven years of decentralisation, local councils are not perceived to be effective at fisheries management: The clearest consensus in the area of governance to arise during the community engagement process regarded the perceived ineffectiveness of local councils. Even within the councils themselves, there was widespread agreement that they did not currently have the capacity to assume their statutory duties in the area of fisheries management. More broadly, fishing communities across the Estuary did not identify closely with the councils or their elected representatives. RECOMMENDATION: For councils to become effective in the area of fisheries management, they must not only build technical capacity in the fisheries sector but also improve their overall legitimacy as representative and accountable democratic institutions. This can be done in part through increasing contact with elected officials and pooling the regulatory resources of the Estuary’s two councils. The Government and partner NGOs must address this as part of the development of an MPA and associated co-management bodies. -

Restoring Food Security to Flood-Affected Families in Sierra Leone

RESTORING FOOD SECURITY TO FLOOD-AFFECTED FAMILIES IN SIERRA LEONE After heavy and above-average rains fell in September 2015 in the Southern Province and Western Area, an estimated 22 000 people were affected and thousands of hectares of land were destroyed. The worst of the damage occurred in Bo, Bonthe and Pujehun districts. Because many households in Sierra Leone depend on agriculture for their food and income, the loss of crops and seeds devastated the food and nutrition security of farmers in these areas, who were already at the peak of the lean season. This project was implemented to immediately improve ©FAO Sierra Leone household food security while allowing farmers to restart agricultural production during the main growing season. WHAT DID THE PROJECT DO? KEY FACTS Critical agricultural inputs (seed rice, vegetable seeds, fertilizers Contribution and simple hand tools) were provided to 1 781 flood-affected USD 475 000 households in Bo, Bonthe and Pujehun districts to restart agricultural production activities. This distribution was Duration supplemented by capacity building in food-crop production. May 2016 – May 2017 Resilience building and disaster risk management (DRM) Resource Partners training improved the capacities of communities to deal with FAO future disasters, built resilience and strengthened preparedness for agricultural risk mitigation. A DRM contingency plan was Partners also developed, and the capacities of the newly established Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry district disaster management committees (DDMCs) were and Food Security, Community Action enhanced. for Rural Development Beneficiaries IMPACT 1 781 flood-affected farmers, After inputs were supplied to the flood-affected households members of the three DDMCs that are and technical assistance was extended, rice yields returned made up of government authorities, to the levels that they were before the flooding, approximately Non-governmental Organizations 1.7 tonnes per hectare. -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

The Ebola Outbreak: Effects on HIV Reporting, Testing and Care in Bonthe District, Rural Sierra Leone A

International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Public Health Action Health solutions for the poor VOL 7 SUPPLEMENT 1 PUBLISHED 21 JUNE 2017 SORT IT SUPPLEMENT: POST-EBOLA RECOVERY IN WEST AFRICA The Ebola outbreak: effects on HIV reporting, testing and care in Bonthe district, rural Sierra Leone A. H. Gamanga,1 P. Owiti,2,3 P. Bhat,4 A. D. Harries,3,5 I. Kargbo-Labour,6 M. Koroma6 http://dx.doi.org/10.5588/pha.16.0087 over in November 2015, although occasional sporadic AFFILIATIONS Setting: All public health facilities in Bonthe District, ru- 1 Bonthe Government cases occurred thereafter. Prior to the Ebola outbreak, Hospital, Ministry of ral Sierra Leone. the country was struggling to recover from civil war Health and Sanitation Objective: To compare, in the periods before and during (MoHS), Bonthe Sherbro and already had serious deficiencies in its health system Island, Bonthe District, the Ebola virus disease outbreak, 1) the submission and and considerable health worker shortages.2,7 The Ebola Sierra Leone completeness of monthly human immunodeficiency virus outbreak adversely affected the quality of health service 2 Academic Model Providing (HIV) reports, and 2) the uptake of HIV testing and care Access to Health Care delivery, and had a major impact on health-seeking be- (AMPATH), Eldoret, Kenya for pregnant women and the general population. haviour and access to care in the community.8,9 3 International Union Design: A cross-sectional study using routine pro- Against Tuberculosis and In all three countries in the region, including Sierra Lung Disease, Paris, France gramme data. -

Darwin Initiative Main Project Annual Report

[Type here] Darwin Initiative Main Project Annual Report Important note: To be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be about 10 pages in length, excluding annexes Submission Deadline: 30 April Darwin Project Information Project Reference 21-013 Project Title Alternative livelihood opportunities for marine protected areas fisherwomen Host Country/ies Sierra-Leone, UK Contract Holder Institution University of Stirling (UoS) Partner institutions Fourth Bay College, University of Sierra Leone Institute of Marine Biology and Oceanography (IMBO), Njala University (NJU), Macalister Elliot and Partners Ltd. (MEP). Darwin Grant Value £247,264 Funder (DFID/Defra) DFID Start/end dates of project 1 Apr 2014 to 31 Oct 18 Reporting period Annual Report 3: 1 Apr 2016 to 31 Mar 2017 Project Leader name Francis Murray Project website/blog/Twitter http://www.stir.ac.uk/aquaculture-mangrove-oyster/ Report author(s) and date Francis Murray, Salieu Sankoh, Richard Wadsworth, William Leschen, James Green, Richard Quilliam, R. Kapindi, Amara Kalone, Nick Shell Table of Contents Darwin Project Information ..................................................................................................... 1 1. Project Rationale .............................................................................................................. 3 2. Project Partnerships ........................................................................................................ 5 3. Project progress -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

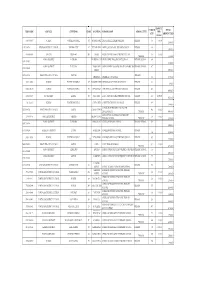

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Bonthe District for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN BONTHE DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount EMIS Name Of School District Chiefdom Address Headcount Total to School Per Child Bonthe 1 320401214 Ada-Gorvie Primary School Imperri Moriba Town 320 10000 District 3,200,000 Bonthe 2 320401207 Ahmaddiya Muslim Primary School Imperri Mogbwemo 388 10000 District 3,880,000 Bonthe 3 320401215 Ahmaddiya Primary School Imperri Moriba Town 254 10000 District 2,540,000 Bonthe 4 320902226 Ansarul Islamic Primary School Imperri Modagbar 300 10000 District 3,000,000 Bonthe 5 320601205 Bonthe District Committee Primary School Kpanda Kemo Kobotu 228 10000 District 2,280,000 Bonthe 6 321001208 Bonthe District Education Committee Sogbeni Moyorgbor 192 10000 District 1,920,000 Bonthe 7 321001212 Bonthe District Education Committee Sogbeni Semabu 316 10000 District 3,160,000 Bonthe 8 321101202 Bonthe District Education Committee Yawbeko Mokosie 261 10000 District 2,610,000 Bonthe 9 321001209 Bonthe District Education Committee Sogbeni Naije 207 10000 District 2,070,000 Bonthe 10 321101208 Bonthe District Education Committee Yawbeko Senehun 304 10000 District 3,040,000 Bonthe 11 320401216 Bonthe District Education Committee Boi-Tia Primary School Imperri Moriba Town 602 10000 District 6,020,000 Bonthe 12 320503214 Bonthe District Education Committee Home Economics Jong Mattru 391 10000 District 3,910,000 Bonthe 13 320501219 Bonthe District Education Committee Primary Jong Senehun 150 10000 District 1,500,000 Bonthe 14 320501201 Bonthe District Education -

Sdi 2020 Sierra Leone Final Draft

MARCH 2021 BROADENING ACCESS AND QUALITY: CITIZEN’S FEEDBACK ON THE STATE OF HEALTH AND EDUCATION SERVICES IN SIERRA LEONE Table of Contents FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................... 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 6 1.1. BACKGROUND AND SCOPE OF THE SDI .......................................................................................... 6 1.2. METHOD ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3. SUMMARY RESULTS .................................................................................................................. 7 1.3.1. OVERALL FINDINGS ON BASIC EDUCATION AND HEALTH ................................................................. 7 1.3.2. SUMMARY FINDING ON BASIC AND SENIOR SECONDARY EDUCATION SERVICES ................................... 8 1.3.3. SUMMARY FINDINGS FOR HEALTHCARE SERVICES ....................................................................... 10 1.3.4. RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................................... 10 2. SDI METHODOLOGY AND SCORING ....................................................................................... 12 2.1. DATA COLLECTION ................................................................................................................. -

Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment in Mangrove Regions of Sierra Leone

Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment in Mangrove regions of Sierra Leone Full Report January 2018 This work was conducted under the USAID-funded West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA BiCC) project. The report is an unabridged version of the official USAID report by the same name published as an Abridged Report in May 2017, and available at http://www.ciesin.columbia.edu/wa-bicc/wa-bicc-ccva-abridged-ff.pdf. The report was prepared by the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) of the Earth Institute of Columbia University. The vulnerability assessment was led by CIESIN under contract with Tetra Tech, and CIESIN also led the analysis and report development. In addition to the CIESIN lead researcher, Sylwia Trzaska, the field research was conducted by a team comprised of representatives from the WA BiCC technical unit in Freetown, Fourah Bay College, Njala University, the National Protected Areas Authority (NPAA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food Security, the Ministry of Lands, Country Planning and Environment, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Conservation Society of Sierra Leone and other stakeholders. The authors of the report are Sylwia Trzaska, Alex de Sherbinin, Paola Kim-Blanco, Valentina Mara, Emilie Schnarr, Malanding Jaiteh, and Pinki Mondal at CIESIN. The team wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Zebedee Njisuh, Aiah Lebbie, Samuel Weekes, George Ganda and Michael Balinga. A full list of field research staff can be found in Annex 5 of this report. Without their hard work and dedication under challenging conditions, this vulnerability assessment would not have been possible.