Street-Connect-Children-In-Dhaka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sylhet Govt. Model School & College

Sylhet Govt. Model School & College East Shahi Eidgah, Sylhet. Student ID S.SL Student ID NAME CLASS SECTION REMARK 1 21061001 ABU TAHER VI A 2 21061002 Ahsan Islam Rahat VI A 3 21061003 AMAN AHSHAN SIDDIQUE VI A 4 21061004 ARAFAT HAQUE VI A 5 21061005 Dewan Shakib Ahmed VI A 6 21061006 DILARA AKTER PRIYA VI A 7 21061007 EATAHAD KHAN ARAFAT VI A 8 21061008 FAHMIDA AKTHER POSPO VI A 9 21061009 FAIZA AKTER FARIHA VI A 10 21061010 FATIHA JAHAN ORPA VI A 11 21061011 Fatima Jannat VI A 12 21061012 GULZAR KHAN FAHID VI A 13 21061013 Iftekhar Mahmud Akib VI A 14 21061014 ISRAT JAHAN NIMU VI A 15 21061015 KAZI UMME NOWRIN MOHEMA VI A 16 21061016 Lamisha Hussain Shuva VI A 17 21061017 MAFURA SULTANA MIM VI A 18 21061018 Mahin Ahmed VI A 19 21061019 MD SAKIB UDDIN VI A 20 21061020 MD. ABDUL MALIK KHAN MARJAN VI A 21 21061021 MD. AHADUL ISLAM MILAD VI A 22 21061022 MD. AL AMIN AHMED TOWSIF VI A 23 21061023 MD. ARIFUL ISLAM VI A 24 21061024 MD. ISMAIL ALI VI A 25 21061025 Md. Kamrujjaman Khan Siyam VI A 26 21061026 MD. MAMUN MIAH VI A 27 21061027 MD. MIZBA UDDIN RIAD VI A 28 21061028 MD. MONZUR HUSSEN NUMAN VI A 29 21061029 MD. PAVEL AHMED CHOWDHURY VI A 30 21061030 MD. SHAHRIAR AHMOD SAMIR VI A 31 21061031 MOHAMMED NAFIS FUAD VI A 32 21061032 MOHONA AKTHER VI A 33 21061033 MST SUMAYA AKTHER SANIA VI A 34 21061034 MST. -

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University Admission Test 2019-2020 1St Waiting List by Roll

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University Admission Test 2019-2020 1st Waiting List by Roll Roll No Name Total Score Merit E00063 LIMON AHMED SUZON 61.030 824 E00090 SALIM HOSSAIN 59.900 1087 E00095 MARUFA JANNAT SONALI 60.190 1024 E00116 SHERAJAM MONIRA TASNIM 62.500 587 E00156 S. M. SHARIA ISLAM RIFAT 62.120 641 E00172 SANJIDA HAMID JYOTI 62.500 582 E00223 SITU PARNA RAY 60.970 837 E00240 SIBBIR AHMED SIFAT 60.610 919 E00253 MOUMITA RANI 60.710 896 E00351 FARJANA AKTAR 62.060 647 E00377 ARNOB ALLAWI 59.780 1109 E00392 NOWSHINTABASSUMEMA 60.910 852 E00517 SHIMA KHATUN 60.160 1035 E00623 MARIAM AKTER MIM 60.160 1036 E00668 FAYSHAL MAHMUD 60.120 1044 E00700 ESMETA SULTANA SHELA 61.040 822 E00707 MD. BULBUL HASAN 60.590 922 E00753 OLIUL ISLAM 60.000 1064 E00797 MD. ARIF PRODHANIA 61.160 790 E00853 SATHIA SULTANA 61.780 693 E00884 RUBEL HOSEN 62.240 628 E00890 MD LIKHON HOSEN 61.060 818 E00914 MD. YOUSUF ALI 60.090 1051 E00918 MST MONIRA KHATUN 62.160 638 E00946 MD. REZAUL ISLAM 60.940 844 E00985 SHAHANA AFROZ JOTY 61.590 722 E01047 PRITHA SEN 62.370 609 E01055 MD HRIDOY ISLAM 62.560 571 E01175 SABBIR 61.000 831 E01206 POBITRA KUMAR BHOWMICK PIASH 62.500 583 E01213 MD. RAKIBUL ISLAM 62.250 625 E01244 SANGIDA ISLAM NISHAT 60.030 1059 E01284 RAFI AHMED 61.090 812 E01347 MD. MAHADY HASAN MAMUN 60.190 1029 E01387 SADIA AFRIN 62.430 596 E01405 MD. NAIMUL HASAN NAYEM 61.000 834 E01554 ASHIK CHOWDHURY AUYON 60.280 993 E01622 MST. -

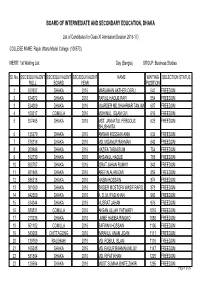

Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Dhaka

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DHAKA List of Candidates for Class XI Admission(Session 2016-17) COLLEGE NAME: Rajuk Uttara Model College (108573) MERIT: 1st Waiting List Day (Bangla) GROUP: Business Studies Sl. No. SSC/EQUIVALENT SSC/EQUIVALENT SSC/EQUIVALENT NAME WAITING SELECTION STATUS ROLL BOARD YEAR POSITION 1 523937 DHAKA 2016 MARJAHAN AKTHER OSRU 547 FREEDOM 2 634072 DHAKA 2016 RAFIUL HAQUE RAFI 554 FREEDOM 3 524009 DHAKA 2016 JOARDER MD.SHAHRIAR TANJIM 607 FREEDOM 4 150317 COMILLA 2016 MOHINUL ISLAM OVI 616 FREEDOM 5 527465 DHAKA 2016 MST. JANNATUL FERDOUS 625 FREEDOM SHUSHMITA 6 125270 DHAKA 2016 ANWAR HOSSAIN ANIK 638 FREEDOM 7 576316 DHAKA 2016 MD. MIZANUR RAHMAN 642 FREEDOM 8 200946 DHAKA 2016 NAZIFA TABASSUM 754 FREEDOM 9 512730 DHAKA 2016 AHSANUL HAQUE 785 FREEDOM 10 506707 DHAKA 2016 ISRAT JAHAN RUMKY 843 FREEDOM 11 651948 DHAKA 2016 AREFIN ALAM OMI 856 FREEDOM 12 586518 DHAKA 2016 NASIM HOSSAIN 874 FREEDOM 13 501060 DHAKA 2016 SIKDER MOSTOFA WASIF RAFID 878 FREEDOM 14 642500 DHAKA 2016 A. S. M. IFAD KHAN 966 FREEDOM 15 534344 DHAKA 2016 NUSRAT JAHAN 976 FREEDOM 16 580831 COMILLA 2016 AHSAN ULLAH PATWARY 1016 FREEDOM 17 213236 DHAKA 2016 UMME HABIBA RINGKO 1080 FREEDOM 18 551102 COMILLA 2016 SAFWAN HOSSAIN 1106 FREEDOM 19 543658 CHITTAGONG 2016 IMRANUL ANAM JIDAN 1111 FREEDOM 20 139769 RAJSHAHI 2016 MD. ROBIUL ISLAM 1116 FREEDOM 21 165248 DHAKA 2016 MD. FAIJUR RAHMAN NILOY 1147 FREEDOM 22 581864 DHAKA 2016 MD. RIFAT KHAN 1225 FREEDOM 23 138564 DHAKA 2016 MOST SUMAIA BINTE ZAKIR 1295 FREEDOM Page 1 of 25 Sl. -

According to Roll (Total-139) University of Rajshahi Admission

University of Rajshahi Admission Test 2017-2018 Faculty of Arts Unit-A (Group-A1) 3rd Merit List Eight Departments According to Roll (Total-139) MERIT ROLL NO. CANDIDATE NAME FATHER'S NAME MARKS DEPARTMENT CATEGORY AFTER VIVA A10406 MST . AFROZA SULTANA TOMA MD. ANWAR SHARIF 61 459 Language (Sanskrit) Merit A10427 MOHAMMAD HUSAIN KHAN HALIMUR RASHID 54.5 988 Arabic Dakhil/Alim Quota A10455 SHARMINNAHAR MD. AFSAR ALI 60.75 480 Philosophy Logic Quota A10589 MD. TUHIN RAHMAN MOHAMMAD ALI 61 478 Language (Urdu) Merit A10679 THAKBIR HOSSAIN MD. TARA MIA 60.5 511 Philosophy Logic Quota A10777 MD. AL AMIN ISLAM MD. QURBAN ALI 60 546 Philosophy Logic Quota Page 1 of 10 MERIT ROLL NO. CANDIDATE NAME FATHER'S NAME MARKS DEPARTMENT CATEGORY AFTER VIVA A10791 AL MAMUN SHOYEB SHEIKH 53.75 1010 Persian Language and Literature Dakhil/Alim Quota A10816 MD. WASIM MD. SAMSUL HOQUE 54.25 996 Arabic Dakhil/Alim Quota A11095 TANVIR AHMAD GIASH UDDIN 54.5 991 Arabic Dakhil/Alim Quota A11176 MD. RAYHAN PARBHEZ MD. ANWAR KHAN 61.5 432 Islamic Studies Merit A11258 MD. RAISUL ISLAM MD. SAIDUR RAHMAN 61 464 Persian Language and Literature Merit A11446 MD. ABDUR RASHID MD. MAJIBAR RAHMAN 60.75 489 Persian Language and Literature Merit A11623 ABDULLAH AL FAHIM ABDUR RAHIM 55.25 977 Arabic Dakhil/Alim Quota A11626 MD. ROBIUL ALAM MD. NUZRUL ISLAM 61 466 Language (Sanskrit) Merit A11680 MD. SUMON ALI MD. SAHIDUL ISLAM 54.75 984 Arabic Dakhil/Alim Quota A11789 SADIA SULTANA MAHBUBUR RAHMAN 54.5 990 Arabic Dakhil/Alim Quota A12344 MD. -

{L!1Frosffif66tf6,Wst

'- rifi.-/-.fl{n -:lr.'., /1,/ ,ir X"r 'i,i' {l!1frosffiF66Tf6,Wst ,,,$iih+*i\. l'-Jtr:rtl..l.i, - Q$:+-,i'9' )e-)8, wHFt a<lu, <-$-fr<lq'K, EIsl- )\rD I CT[{: bUGeBQ.U, bggbB)e, TIIS: b99bb)) \o)q rTfFK ffi..{qfr qfu"R 1tuqlsfm'ffrq'KslR+.f D:/Khairuzzaman Chorvclh ury/.l SC Schol arsh ip 20 I 7.doc a;;n;. ,*:t'" 1'r, ,'ts, lf,, /t "i.,:, 1' $$fr-s s E;mT'|lTft-sfrsl c{M, urc-l- ,-t.'t:tl'l,,,.i ,, \.'(t*i"*'#' )\-tr(...{.-^./ " ii sr[t" {{:T: )/rtftis/qooc/ ul.k{ , ob-o8-{o)b RSt-q frqt, \o)r firo< qfinK EE fitrFFr-sB (mecfr) ffiT-K T6rtTm{ &fup e c{ltv-i "cr3qft" o qqlq 'iTKl<t{fr" elqrn r EmFtrytqRqgLq-{ el-qI\- {q.: It$fr-s. s e1.oQ..oooo.))t.e).oou.)\-bbc, vlRri: )b-oe-)u I E"F(s R'Es e {cq< cqfuTo {t<ifus e Emrl<lfrs FtE{ c<r6, urfl- ,{< to)1 wro< qtm-{ 5,{ 4ffieffi (cerq{fr) qfts'K s-EfrI_ar< &fus W{o -ir6 cqFil trNTfimr "cq<-qfu" e "qHH"r{&" eqr{ qcfl q gl.Fr$-r qfin qcTt-6q s-$ I x<-oR Fxq e freTret s-$tft 1fu< $-{t I q q-{Rt qr< Ifr eqft-fi ma fir[qifu fill e frfuTtrt.Tqfr? s-$-Ers c:rn DErs r @ ) I s) 1ft{ curcq-d $bqrc Fis'rfr ar Frmr qfut"r{ 6q6q afiqps q(bfefqcr rer< Be.l qcrcq m E&ttr+< ${ Ur$?r o<I qr:rce r Bs qfrfr.r q<'rc.m ersll;nq eqrq q'r(t(\' sfuTE qfut-r{ 6a6a ffi q6q Nlvlc{s 1ft< wdBr€-I-fl F{cu 1 qERq. -

{Frflfr-Svffirwt6{6,Wst

d {frflfr-svffiRwt6{6,Wst )e-)8, qr{t5t mls, <s'fu{, El$t-)q)) ffi1{ 8 EgCaSqE, bggbu)e, +J[g 8 bgvbb)) \o)q rtrcFm equ'eqfr fu @ ErFrsr s $pqtrrrfrsfiTf DT$[ {f$fr-$ *ffi' ffiM, I rcl: l/"VT&Aooc./)1 ulRct, >:/or/ru Frr , Q.o)q m+* Ewflvfr-r qtEffi (cfucrr$ ffiry'6pa1q6rys&&roqq qFtl<"r{fr" r<k6{ "6qqfr e elq6e|qrrr r {s: {t{rfrT s BE'FIsrqRqisffi{TBFFq(-e1.o\.oooo.))r.e).oov.)\-uar vtfr{-qv/rr/tqqq B+fF R'cs s wqil cEfrls- Tr$fr-s e EmqFofi-s fist ffiM , Etsr €r Q.o)l fi6{ir qtffi qftq'r< Emt<ifro T-{lTrfiT &frrs ffi "k6 fr6r{, {t{fr"r s rrfits fimr ft\s[rr slGmf W fisTfifum "6q1qftrr s "qf{f<"r1&" qq1-E srt qrEl r qrotfr frsr s ftB{1qt qWtft q slFr$t eicm-E qcrq {& +-*t I e qqr rg q-{qjt Ifr Eqtr+{ frcT <fu fiRT fil&rtEt N6{ EEcs qr< | lffi ) I (O Ifur cutrqlB fislft cq Frmt Eetr{ celrs etftst{ qi-wqr smrq fit EB$to< {tr ql-sm q<\. EB&r{ q{rcdm qttrffi Eqtq Tlnrm WTr Eery 6arc-s brfi BrsET o<c< r 1fu* 6I{tE'lo)t rTlrerWt{mq6e csl6fu 6st6offt{qq{ ffi 1 rtfi?' qfq/ffim{ q-{$t ql''ffre 1+; <RElrqrrr{ q(s'Er{ | ('r) csEB F|.vTffmr {q'[E{c[, frqrqm ffi B{Re \e rrmt{srdra qkffi flrqrm Ifu sq1"r6-stq5q 1 q (s) @'erom q$tt, qI< rs trifiq qt{v fr(Rv I Emfwrr<Iffi c-?rsK c$l;r o.r{GI qt qffi{ otKm cqfikilt et <T <t&q re-<-cs r qvrsGr qTs qftsst{qwq \ r rRsm-rrEr xqfr lw{6rtq-o fi$t 1&-sFfar Rr< r xqs (q-*Tlqr) qr{ ({ Etg T{ 6s.l{ fisT Eefim 1fr mnqixt s.6s( EC{ {t r +|{ct rK-stR qtq qT{lft q-dr{mlfre- q{rsl;re ft{FI EB6Tc{ ffi t& to*t< Gl'tr rs i{<( w{ncstfiv ftt1 E&.&tcr q{rs{s'lE q-{ ef.lr qc< "ffb ffi (qo ilel Rcw< r e r TE Ifrt cs-<6r FRfrv qasl-{ v<.$.{q6r$ft Efrcf Fr+'Eftm 16,o fl<TTrylm q<\ ftGqlqt< wrrr-{Tq6 crtvrao qfi qr{ r qffis on-c< qT Eqrq csF vft<t Frsffir1& r 8 I :ry-q-q {&qTg ftsTff kqI c<Er+ q${rffi {r+Iri Elv' Gl-trr I {<-$l-< q{G[lfrs 6q6 fi6y qe*lt pt'+tfrrq-< {tEtg ffi ceft-s rorq qtfr"s c<vq fift T-{cv. -

College Admission Result

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DHAKA List of Students of HSC Admission (Session 2013-2014) COLLEGE/THANA/ZILLA (EIIN): ADAMJEE CANTONMENT COLLEGE/DHAKA CANT./DHAKA MAHANAGARI (107855) SHIFT: DAY (BANGLA) EXPECTED GROUP: SCIENCE SL NO ROLL NO SSC PASS BOARD SSC PASS YEAR NAME GPA SELECTION STATUS APPLIED QUOTA 00001 100110 SYLHET 2013 MD. TAUFIQUE SHAWON 5.00 Merit 00002 100122 SYLHET 2013 MD.FAHIM BHUIYAN ABAK 5.00 Merit 00003 100244 SYLHET 2013 MD. ABDUN NUR BHUIYAN 5.00 Merit 00004 100310 DHAKA 2013 TAHMEED ASHAB 5.00 Merit-EQ EQ 00005 100333 SYLHET 2013 AKIB IRFAN 5.00 Merit 00006 100411 RAJSHAHI 2013 NAJIA IFFAT BAROTA 5.00 Merit 00007 100564 JESSORE 2013 TAHMINA HAQUE URMI 5.00 Merit 00008 100621 RAJSHAHI 2013 MD. SHIBLY NOMANY SAIKAT 5.00 Merit 00009 100920 SYLHET 2013 SATYAKI BANIK 5.00 Merit 00010 100921 SYLHET 2013 ANIRUDDHA BHOWMIK 5.00 Merit 00011 101155 RAJSHAHI 2013 ARUP KUMAR PAUL 5.00 Merit 00012 101219 RAJSHAHI 2013 MST. SUMAIYA JASMINE 5.00 Merit 00013 101336 CHITTAGONG 2013 IFRAN AHMAD 5.00 Merit 00014 101338 CHITTAGONG 2013 IMRAN HOSSAIN 5.00 Merit 00015 101354 CHITTAGONG 2013 KASHEM BIN ASHRAF 5.00 Merit 00016 101398 SYLHET 2013 DILRUBA HOSSAIN DOLON 5.00 Merit 00017 101587 CHITTAGONG 2013 NUSHRAT AFRIN SHITHIL 5.00 Merit 00018 101590 CHITTAGONG 2013 TAMANNA YEASMIN 5.00 Merit 00019 101596 DHAKA 2013 TAHSIN TASNIM ATASHI 5.00 Merit 00020 101621 CHITTAGONG 2013 MOHAMMAD TARIQUR RAHMAN 5.00 Merit 00021 101759 SYLHET 2013 BIJIT KANTI DEB NATH 5.00 Merit 00022 102134 DHAKA 2013 MD. -

I Bv‡Gi Zvwjkvt

wSbvB`n cwj‡UKwbK BÝwUwUD‡Ui (2019-20) 1g ce© wmwfj †UK‡bvjwRi 1g wkd‡Ui QvÎ/QvÎx‡`i bv‡gi ZvwjKvt µwg K¬vm †ivj ‡evW© †ivj ‡iwRt bs QvÎ/QvÎxi bvg wcZvi bvg gšÍe¨ K bs I 1g wkdU I 1g wkdU I †mkb MD SHAKHAWAT HOSSAN 1 428981 64111 SEZAN MD ABDUL LATIF 1502052396/19-20 MD AKIBUL HAQUE 2 428983 64151 SAKKHOR MD MOKSUDUL HAQUE 1502052394/19-20 3 64109 MD. AMIN UDDIN MD. ALEK RAHMAN 428984 1502052393/19-20 4 64145 MD. FIROZ AL MAMUN MD. JHUMUR ALI 428985 1502052392/19-20 5 64146 MD. BADSHA RAHMAN MD. KHAIRUL ISLAM 428986 1502052391/19-20 6 64128 MD. MAHABUB HASSAN MD. ESKENDER ALI 428987 1502052390/19-20 7 64135 MD. RAKIBUL ISLAM MD. EMAROT ALI 428988 1502052389/19-20 8 64132 MD. MEHEDI HASAN MD. MOFIJUR RAHMAN 428989 1502052388/19-20 9 64121 ABDULLAH USMAN GHONI 428990 1502052387/19-20 MD. FAYSAL AHMMED 10 428991 64125 RATON MD. FAZLA RABBI 1502052386/19-20 11 64126 MURSHIDA AKTER MITHI MD FAJLUR RAHMAN 428992 1502052385/19-20 12 64102 MD NABIL WALID MD ANAYET HOSSAIN 428993 1502052384/19-20 13 64105 AFRIN SULTANA MD. ABUL HOSSAIN 428994 1502052383/19-20 14 64137 MD. SHIMUL HASAN MD. MUKTAR HOSSAIN 428996 1502052380/19-20 15 64110 ABDUL GOFUR GOLAM RASUL 428997 1502052379/19-20 16 64115 ASIKUR ROHAMAN BOKUL BISWAS 428998 1502052378/19-20 17 64138 ASHIK MIA RABIUL ISLAM 428999 1502052377/19-20 18 64117 MOHAIMINUL ISLAM JITU MOFAZZEL HUSAIN 429000 1502052376/19-20 19 64106 MST. TEYA KHATUN MD. -

F.Name M.Name District Category 1 19010005 KAMRUL ISLAM PARVEL ANIS MADBAR POLI AKTHER SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 2 19010006 MD

Wage Earners' Welfare Board Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment PEC Scholarship-2019 SL Student Code Student Name Parents Address Gender Results Info F.Name M.Name District Category 1 19010005 KAMRUL ISLAM PARVEL ANIS MADBAR POLI AKTHER SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 2 19010006 MD. SABIT ISLAM MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM FATEMA AKTHER SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 3 19010010 MANIK SORHAB SOYAL KOHINOR SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 4 19010016 SABBIR HOSEN AMIR HOSEN MAZI SERINA SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 5 19010019 SABBIR AHAMMED MOZIBAR KHA SARMIN AKTHER JORNA SHARIATPUR Female PEC 6 19010021 IMRAN KAYES SIYEM MD. MONIR MAZI ROJINA BEGUM SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 7 19010031 ADIYAT AWLAD HOSSAIN MONI BEGUM SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 8 19010034 TANVIR ABUL BASHAR SERINA BASHAR MELI SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 9 19010044 MD. BIN SAFOYAN ABDUL HALIM AKHON SALENA PARVIN SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 10 19010045 MD. TOYIB MD. SAHJANAKON MRS MONI SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 11 19010046 RADOUN SIKDER NASIR UDDIN ASMA SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 12 19010048 TASNIM ZARIN ABUL KALAM ALPONA SHARIATPUR Female PEC 13 19010050 NAFIZA RAHAMAN MD. SIDDIQUR RAHMAN NAZMUN NAHAR SHARIATPUR Female PEC 14 19010058 SADIA AFRIN KAMAL HOSSAIN KHAN JOLEKHA BEGUM SHARIATPUR Female PEC 15 19010060 MD. ABU BAKKAR SIDDIK LATE MD. ATAUR RAHMAN SAIFUN NAHAR SHARIATPUR MALE PEC 16 19010076 SURIYA AHAMMAD SAMIM AHAMMAD SOBORNA AHAMMAD SHARIATPUR Female PEC 17 19010081 SADIA AKTER SATTAR HAWLADER SAHANAJ BEGUM SHARIATPUR Female PEC 18 19010082 SARMIN AKTER SOHADA SOHAG KHAN LIPI BEGUM SHARIATPUR Female PEC 19 19010087 ARIFA SAHABUDDIN SABINA -

3Trtr Ecm'?Srq € Er{G- Ffi;Rqa [D{R-Bq.O\9 >Itttif 4+ Safiz

3trTr ecm'?srq € er{G- ffi;rqa [d{r-bQ.o\9 >iTtTiF 4+ Safiz .e e.o FFst<Gi f<. er-fr. EGFmrkr" ffiE-elr<Fl "J-.iil erf,fr.r.i ergp fr1RlrreL=r< )s-lo:c ,g kq-r<i c=n(,i< :a <ca{ sE< q+r cq {sq qrc<a{sl? sF -]e'Fll q(rfolqccr< qqr F-.ir6-s Qellcs qGil s1(h3 T<X ;t< qTflr< 6lz1 {< \s 4ln €EI)Tlcsl {<39 o<l I R:E: wc<E{+r-Arh= g'Ri ffisl< Fm< ffi \e F{ n.< flAq-I rsF< s-{-l(s ta. TS] TC< ffirnLq-< 64tE{ c<6 .g sC<<ryt?&< sfgrq Gyta1 {lC<t , (srGFtl=I .s ,l:r-lrrfu. -fu +ffi f-P4Fa1 io:u-to >q :N <{ F. ea-tr. {AlFnrrks. reugl<in e fi'slrr mp1 e(fr5lcr .c zrg@ k-.Jf<rarlo?l "r;1ql Khulna University of Engineering & Technology 1st Year B.Sc. Engg., BURP & BARCH Admission Test (2016-2017) List of Eligible Candidate APPL NO. ROLL NO. APPLICANT NAME FATHER NAME 200002 10160 SHUDDHA SHAHRIAR SWADHIN MD. SOHRAB HOSSAIN SHEIKH 200003 12701 SHANKHA SHUBHRA SARKAR SHASHANKA SHEKHAR SARKAR 200004 12786 MD. NAFIZUL ISLAM MD. ZAKIR HOSSAIN 200005 18904 ZAHIRUL ISLAM TOWHIDUL ISLAM 200006 12792 MD. EHSANUL HAQUE MD. ABDUS SALAM 200007 13308 MD. HASIBUL HASAN LOOKMAN HEKIM 200008 18200 MD. NAIMUL HAQUE MD. OBAYDUL HOWLADER 200010 17292 ABID HASAN MAHMUD ABDUL AHAD 200011 10547 ABU SAHRIAR AHMED MD. FORHAD HOSSAIN 200012 13731 MUNSHI SAIFUZZAMAN MUNSHI ALIMUZZAMAN 200013 18119 UN-NISHA-LIAQUAT USHA M LIAQUAT ALI KHAN 200014 18862 M. -

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science And

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University Admission Test 2019-2020 1st Waiting List By Roll (Business) Roll No Name Total Score Merit F00058 MST. SATHI AKTER 63.220 285 F00152 NISHAT ARA ROSHNI 62.220 352 F00204 OPPY BHUIYA 61.780 379 F00205 MD. HASIBUR RAHMAN 61.440 400 F00211 PARVEZ HOSSEN 62.530 323 F00236 PRONOB GUPTO 60.880 441 F00356 RIPA KHAN 62.200 353 F00363 MD SHAKIL HOSSAIN 62.660 316 F00395 MD.FOYSAL 62.660 317 F00455 MD. SHAHINUR ISLAM 61.380 402 F00516 MD. ABDULLAH AL KAFI 62.000 365 F00616 IMTIAZ UDDIN KHOUNDAKER 62.130 357 F00721 MD HRIDOY ISLAM 60.310 496 F00772 SUMAN BISWAS 60.810 443 F00827 MD. MARUF KHAN 62.780 307 F00887 BIJOY BAISHNAB 61.130 425 F00888 MD. SOHAN HOSSAIN 62.860 302 F00920 DILARA ARFIN DIPTY 61.840 377 F00982 MASUM BILLAH 60.630 466 F00999 RAHMAT ULLAH BABU 60.910 437 F01043 PALLOBI RANI DAS 63.750 251 F01115 MD. ASRAFUL HUDA MISHU 62.160 356 F01157 HUMAIA AKTER TOFA 62.370 340 F01294 DIPU KUMAR SHAHA 60.460 480 F01496 MD SAJIB HOSSAIN 63.310 277 F01538 NAEEM HOSSAIN 60.960 432 F01599 IMTIAZ KABIR MARUP 62.450 329 F01616 TAMANNA KHATUN 60.250 500 F01693 MD. ASIK AL RAZ KHAN 62.120 358 F01704 TUHIN AHMED 61.600 389 F01831 MD.BAHADUR 61.560 392 F01861 ADNAN ALAM MALLIK 62.100 360 F01941 G.M.SAIF SAFAYET KHAN 60.940 433 F01987 SOLAYMAN MUNNA 61.250 414 F02018 MAHMUD TUSER FARAJI 61.880 373 F02038 JAYA ACHARJEE 63.140 287 F02060 SADIA SULTANA SHATHI 62.440 330 F02136 MD.NAYEEM MIA 62.350 342 F02214 KABBO SAHA 61.230 417 F02246 MEHADI HASAN SHANTO 63.410 270 F02254 JASIA ISLAM BANNA 63.270 281 F02323 RAKIBUL HASAN TUHEL 63.290 279 F02384 SHEIKH MAHDIUZZAMAN 62.370 339 F02432 PRONOY CHANDRA ROY 62.780 308 F02437 ZAHID BIN FIROZ 61.310 406 F02450 NAZMA KHATUN 62.070 363 F02470 RAFSAN BARI MIAD 60.630 468 F02704 EMON ROY 62.530 322 Page: 1 of 6 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University Admission Test 2019-2020 1st Waiting List By Roll (Business) Roll No Name Total Score Merit F02801 MD. -

Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Dhaka

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DHAKA List of Candidates for Class XI Admission(Session 2016-17) COLLEGE NAME: Rajuk Uttara Model College (108573) MERIT: 2nd Waiting List Morning (Bangla) GROUP: Business Studies Sl. No. SSC/EQUIVALENT SSC/EQUIVALENT SSC/EQUIVALENT NAME WAITING SELECTION STATUS ROLL BOARD YEAR POSITION 1 651855 DHAKA 2016 SUMAIYA SABRIN 899 DISTRICT 2 515699 DHAKA 2016 OITIJJO JOANNA HALDER 901 DISTRICT 3 651906 DHAKA 2016 MAHMUDUL HASAN MRIDUL 912 DISTRICT 4 552185 COMILLA 2016 ISRAT JAHAN 919 DISTRICT 5 160922 COMILLA 2016 MD. SHAFE MONSI 921 DISTRICT 6 576625 DHAKA 2016 TAMANNA AKTER 926 DISTRICT MERIT: 2nd Waiting List Morning (Bangla) GROUP: Business Studies Page 1 of 22 Sl. No. SSC/EQUIVALENT SSC/EQUIVALENT SSC/EQUIVALENT NAME WAITING SELECTION STATUS ROLL BOARD YEAR POSITION 7 509452 DHAKA 2016 ROKEIYA TAHIA THAKUR 893 GENERAL 8 640616 DHAKA 2016 TONU MONDOL 894 GENERAL 9 512695 DHAKA 2016 ASMAUL HUSNA 895 GENERAL 10 632575 DHAKA 2016 MST.KULSUM AKTER 896 GENERAL 11 512962 DHAKA 2016 TANBID MEHDY SAKIB 897 GENERAL 12 119989 DHAKA 2016 REHANA AKTER TONNI 898 GENERAL 13 651855 DHAKA 2016 SUMAIYA SABRIN 899 GENERAL 14 563264 DHAKA 2016 FARIN TASFIA ESHA 900 GENERAL 15 515699 DHAKA 2016 OITIJJO JOANNA HALDER 901 GENERAL 16 630649 DHAKA 2016 JANNATUL FERDOS MUNNY 902 GENERAL 17 511835 DHAKA 2016 ABDULLAH MAHMUD 903 GENERAL 18 504608 DHAKA 2016 TAHNIZ NOOR 904 GENERAL 19 512858 DHAKA 2016 TORUNA AKHTER 905 GENERAL 20 512718 DHAKA 2016 FAHIM-BIN-ELIAS 906 GENERAL 21 112619 DHAKA 2016 AKIB HOSSAIN 907 GENERAL 22 501550 DHAKA 2016 IVANNA SAMANTHA GOMES 908 GENERAL 23 507085 DHAKA 2016 MD.