What Happened to the Berkeley Co-Op?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consent Decree: Safeway, Inc. (PDF)

1 2 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 4 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 5 6 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) 7 ) Plaintiff, ) Case No. 8 ) v. ) 9 ) SAFEWAY INC., ) 10 ) Defendant. ) 11 ) 12 13 14 CONSENT DECREE 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Consent Decree 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 I. JURISDICTION, VENUE, AND NOTICE .............................................................2 4 II. APPLICABILITY....................................................................................................2 5 III. OBJECTIVES ..........................................................................................................3 6 IV. DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................3 7 V. CIVIL PENALTIES.................................................................................................6 8 9 VI. COMPLIANCE REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................6 10 A. Refrigerant Compliance Management System ............................................6 11 B. Corporate-Wide Leak Rate Reduction .........................................................7 12 C. Emissions Reductions at Highest-Emission Stores......................................8 13 VII. PARTICIPATION IN RECOGNITION PROGRAMS .........................................10 14 VIII. REPORTING REQUIREMENTS .........................................................................10 15 IX. STIPULATED PENALTIES .................................................................................12 -

Docket No. Fda–2011–N–0921

DOCKET NO. FDA–2011–N–0921 BEFORE THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION COMMENTS OF THE AMERICAN HERBAL PRODUCTS ASSOCIATION ON PROPOSED RULE for STANDARDS FOR THE GROWING, HARVESTING, PACKING, AND HOLDING OF PRODUCE FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION November 22, 2013 Docket No. FDA–2011–N–0921 November 22, 2013 Prefatory remarks ................................................................................................................................ 1 1. The broad and deep impact of the new regulations necessitates regulatory restraint ...................... 2 2. The same controls are neither necessary nor appropriate for non‐RTE foods as for RTE foods ......... 3 3. Wherever possible, food processors rather than farmers should ensure the biological safety of food ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Wherever possible, FDA should avoid burdening farmers and should rely on food processors rather than farmers to ensure biological safety ................................................................................ 7 3.2 Farmers are generally ill‐equipped to comply with either Part 112 or 117 ................................. 7 3.3 Food processors are the appropriate entity to ensure the biological safety of food wherever possible ........................................................................................................................................... -

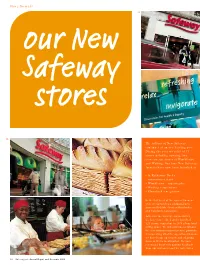

Store Formats a Our New Safeway Stores

Store formats A our New Safeway stores B The roll-out of New Safeway continues at an accelerating pace. During the year we refitted 73 stores including opening two new concept stores at Wimbledon and Woking. Our four New Safeway formats have now been launched at: • St Katharine Docks – convenience store • Wimbledon – supermarket • Woking – superstore • Plymstock – megastore In the first week of the current financial year, we opened two additional new stores in Reddish, Greater Manchester, and Carnforth, Lancashire. Added to the work we did in 2000/1, we have now refitted and relaunched 121 stores, equivalent to 26% of our total selling space. We will continue to roll-out the new formats across our store portfolio, incorporating all of the operational lessons we have learnt up to now and adapting them to fit the local market. We have received a lot of very positive feedback from our customers and we have taken 14 Safeway plc Annual Report and Accounts 2002 Store formats now fully refitted all but one of the 18 convenience stores in our portfolio. All of these stores have achieved industry- leading standards of product presentation. “Fresh to Go” supermarkets We launched the first full prototype at Wimbledon in May 2001 and by the end of the year we had reformatted 66 of our 205 supermarkets. We have created the feeling Fernando Garcia-Valencia Jim Maclachlan Property and Stores Director of a larger store with more space in the Development Director fresh areas and have often introduced cross aisles to make it easier for customers to shop. -

Clarity Telecom Challenging the Global Voip Players

Membership magazine of the IoD in Northern Ireland September / October 2019 Young Directors Conference 2019 Achieving Competitive Edge Page 10 The Twinterview with Conall Laverty, Founder & CEO of Wia Page 26 The Power of PhD Page 34 Clarity Telecom Challenging the Global VoIP Players Page 06 Our Committee Gordon Milligan, Adrian Allen, Bonnie Anley CDir, Barry Byrne, Catriona Gibson, Chairman, IoD Northern The Tomorrow Lab Londonderry Port and Mount Charles Group Arthur Cox Belfast Ireland Harbour Kathryn Thomson, John Hansen, David Henry, Caroline Keenan, Professor Marie McHugh, National Museums NI KPMG Northern Henry Brothers ASM Chartered Ulster University Business Ireland Accountants School Alan McKeown, Sarah Orange, Natasha Sayee, Paul Stapleton, Paul Terrington, Dunbia HNH Human Capital SONI NIE Networks PWC 2 | DirectorNI directorNI Gordon Milligan Chairman’s Message IoD Northern Ireland opefully as you read smart clothing, wearables and 3D Ulster University, we heard about this you have enjoyed printing. It’s always enlightening to the progress and future plans on hear from local NI businesses that some major ongoing infrastructure a good summer and are at the forefront of disrupting projects; including the Belfast are refreshed and the status quo and competing on Transport Hub, the new Ulster re-energised for what a global scale, especially in the University city campus and an HI imagine will be a challenging time healthcare and medical industries. update on the Belfast Regional City ahead as businesses and political Deal. These transformational projects parties start on another round of will have significant positive impact Brexit preparations and discussions to the Northern Ireland economy through the services provided to ahead of the UK’s planned EU exit We have a very our citizens, business, tourism and on 31 October. -

Fiscal Year 2019

Fiscal Year 2019 HCCS ORGANIZATIONAL BUSINESS PLAN Part I: Metrics Part II: Blueprint Part III: Strategic Considerations Hanover Consumer Cooperative Society, Inc. Submitted to the Board of Directors December, 2018 by Edward Fox General Manager Nourish. Cultivate. Cooperate. 1 Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 4 PART I: METRICS Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 6 PART II: BLUEPRINT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 10 Opportunities......................................................................................................................................... 11 Company Summary Overview ................................................................................................................................................ 11 Company Ownership ......................................................................................................................... 11 Vision Statement ................................................................................................................................. 11 Goals ........................................................................................................................................................ -

June/July 2016

FreshJUNE / JULY 2016 DIGEST A P U B L I C A T I O N O F T H E F R E S H P R O D U C E & F L O R A L C O U N C I L 10 Features 8 Inaugural Summit Shines Spotlight on Exploding Category FOCUS ON ORGANICS 13 Southern California April Luncheon EVENT PHOTOS AND THANK YOUS 18 Dressings...Dips...Juices FOCUS ON COMPLIMENTARY ITEMS 22 DLJ Produce Adds Full Line of Organics and Value Added Packaging FOCUS ON EXPANSION 24 Top Chef to Keynote EXPO Breakfast FOCUS ON SOCAL EXPO 26 Tessamae’s: It’s all in the Family 24 FOCUS ON COMPLIMENTARY ITEMS 28 Northern California Expo EVENT PHOTOS AND THANK YOUS 38 4Earth Farms Adds Line of ‘Overseal’ Packaging FOCUS ON ORGANICS 40 Dan Sims Calling it a Career FOCUS ON RETIREMENT 42 Meet Your 2016 FPFC Apprentices PHOTOS AND BIOS Cover design by: User Friendly, Ink. Departments Volume 44, Number 3 JUNE / JULY 2016 FRESH DIGEST (ISSN-1522-0982) is published bimonthly for $15 of FPFC membership dues; $25 4 Editor’s View for annual subscription for non-members by Fresh By Tim Linden Produce & Floral Council; 2400 E. Katella Avenue, 6 Executive Notes Suite 330, Anaheim CA 92806. Periodicals postage By Carissa Mace paid at Anaheim, CA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to 17 Council News FRESH DIGEST, 2400 E. Katella Avenue, Suite 330, FPFC Highlights 38 Anaheim CA 92806. JUNE / JULY 2016 3 Generation Z I went camp- other closeted lifestyles. -

Download (11Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/98784 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 2 o Strategic Groups, Industry Structure and Firms ’ Strategies: Theory and Evidence from the UK Grocery Retailing Industry Francesco Fortunato Curto Thesis Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Warwick Business School University of Warwick England May 1998 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1.0 The Research P- 1 1.1 Structure of the Research P- 5 Chapter 2 The Theoretical Foundations of Strategic Groups: the Harvard Approach 2.0 Introduction P- 9 2.1 The Research Context: Industrial Organisation and the Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) Paradigm p. 10 2.1.1 Firms’ Strategies and the Industry Structure in the SCP Paradigm P- 15 2.2 The Theory of Strategic Groups and Mobility Barriers p. 16 2.2.1 Structural and Endogenous Barriers to Entry P- 18 2.2.2 Barriers to Mobility and Strategic Groups P- 20 2.2.3 The Origins of Strategic Groups and Firms’ Strategic Behaviour P- 21 2.2.4 Intergroup Mobility, New Entry and Mobility Dynamics p. 22 2.3 The Characteristics of Strategic Groups Theory P- 25 2.4 Further Theoretical Development: Porter’s (1979) Theory of a Firm’s Profitability P- 28 2.4.1 Oligopolistic Rivalry and Firms’ Performance p. -

Facility Facility Name Street Address City Name State

FACILITY FACILITY NAME STREET ADDRESS CITY NAME STATE 668 SAFEWAY 2100 RALSTON AVE BELMONT CA 1138 SAFEWAY 1100 EL CAMINO REAL BELMONT CA 697 SAFEWAY 1972 TICE VALLEY BLVD WALNUT CREEK CA 713 SAFEWAY 100 CALISTOGA RD SANTA ROSA CA 768 SAFEWAY 20629 REDWOOD ROAD CASTRO VALLEY CA 790 SAFEWAY 555 BANCROFT AVE SAN LEANDRO CA 797 SAFEWAY 231 W JACKSON STREET HAYWARD CA 911 SAFEWAY 477 W NAPPA ST SONOMA CA 917 SAFEWAY 600 S BROADWAY WALNUT CREEK CA 918 SAFEWAY 6340 COMMERCE BLVD ROHNERT PARK CA 933 SAFEWAY 406 N MAIN ST SEBASTOPOL CA 936 SAFEWAY 710 BANCROFT RD WALNUT CREEK CA 950 SAFEWAY 16405 HWY 116 GUERNEVILLE CA 951 SAFEWAY 867 ISLAND DRIVE ALAMEDA CA 956 SAFEWAY 1799 MARLOW SANTA ROSA CA 967 SAFEWAY 2 CAMINO SOBRANTE ORINDA CA 971 SAFEWAY 22280 FOOTHILL BLVD HAYWARD CA 994 SAFEWAY 1499 WASHINGTON AVE SAN LEANDRO CA 998 SAFEWAY 1115 VINE STREET HEALDSBURG CA 1265 SAFEWAY 2785 YULUPA AVE SANTA ROSA CA 1434 SAFEWAY 9080 BROOKS ROAD WINDSOR CA 1562 SAFEWAY 2751 FOURTH STREET SANTA ROSA CA 1576 SAFEWAY 2300 MENDOCINO AVE. SANTA ROSA CA 2315 SAFEWAY 699 LEWELLING SAN LEANDRO CA 2449 SAFEWAY 3375 JEFFERSON STREET NAPA CA 2456 SAFEWAY 701 SONOMA MOUNTAIN PKWY PETALUMA CA 2457 SAFEWAY 1211 WEST COLLEGE AVE SANTA ROSA CA 2605 SAFEWAY 1026 HUNT AVENUE SAINT HELENA CA 2708 SAFEWAY 2227 S SHORE CENTER ALAMEDA CA 3010 SAFEWAY 4015 E. CASTRO VALLEY BLVD CASTRO VALLEY CA 3011 SAFEWAY 389 S MCDOWELL ROAD PETALUMA CA 3013 SAFEWAY 3680 CROCKER DRIVE STE 100 SACRAMENTO CA 3026 SAFEWAY 2800 YGNACIO VALLEY RD WALNUT CREEK CA 3111 PAK N SAVE 555 FLORESTA BLVD SAN LEANDRO CA 3125 PAK N SAVE 3889 SAN PABLO AVE EMERYVILLE CA 3281 SAFEWAY 2600 FIFTH ST ALAMEDA CA 691 SAFEWAY 1444 SHATTUCK PLACE BERKELEY CA 676 SAFEWAY 1500 SOLANO AVE ALBANY CA 2453 SAFEWAY 1550 SHATTUCK AVE BERKELEY CA 2451 SAFEWAY 1850 SOLANO AVE BERKELEY CA 654 SAFEWAY 2096 MOUNTAIN BLVD OAKLAND CA 908 SAFEWAY 3550 FRUITVALE AVE OAKLAND CA 1119 SAFEWAY 3747 GRAND AVE. -

Somerfield Plc / Wm Morrison Supermarkets Plc Inquiry

APPENDIX B Key aspects of the economic analysis for Stage 1 of the local competitive effects methodology Part 1 Introduction 1. Stage 1 of our local competitive effects methodology involves identifying a local market in which to apply a screening rule. The local market has a product-market dimension (ie which fascias and sizes of store compete with each other) and a geographic-market dimension (ie how wide their customer catchment areas are). This appendix summarizes four key aspects of the economic analysis undertaken at Stage 1. 2. Our findings are that: • the product market used at Stage 1: — should not include the LADs, ie Aldi, Lidl and Netto, nor Marks & Spencer; but — should include all stores of 280 sq metres (3,000 sq feet) or more (including one-stop shops); • the geographic market used at Stage 1 should use 5-minute drive-time isochrones for urban stores and 10-minute drive-time isochrones for rural stores; and • in circumstances where an acquired store’s local market share was higher pre- merger (ie where it appears to have faced less competition) its margins also tended to be higher, especially in rural areas. A corollary of this result is that the local markets for which acquired stores’ market shares have been calculated by Somerfield may be relevant markets, especially in rural areas. 3. The remainder of this appendix is organized as follows. Part 2 reports the results of an analysis of the impact on Somerfield and Kwik Save sales of the opening of various competitor fascias, which helps to define the product market (ie which competing fascias constrain Somerfield and Kwik Save). -

Our New Formats the Key Concept Is the Blending of Catering, Fresh Foods, Ambient Groceries the Plymstock Megastore Is a Landmark in Our Format Development

Chief executive’s review building Our new formats The key concept is the blending of catering, fresh foods, ambient groceries The Plymstock megastore is a landmark in our format development. and a growing range of non-food products and services in a multi-format It demonstrates how we can transform a 28,000 square foot superstore store portfolio. We have now proved that we can deliver in each of our into a 58,000 square foot hypermarket and do so in a way which breaks four formats a distinctive shopping experience which is proving successful. free of the standard model first developed by Carrefour in the 1960s Overall, we now have 121 stores, equivalent to 26% of our selling and subsequently replicated by our competitors in the UK. At the core space, which have been refitted in one or other of our new concepts. of our new megastore format is the Hub, which blends our “Fresh to Go” The sales performance of these stores and the feedback we are receiving and Café Fresco concepts with browsing for books, music, films and from our customers convinces us that we have a winning strategy. magazines in a relaxing environment. Our first new concept convenience store was launched at St Katharine We are on track to complete the reformatting of our entire portfolio Docks in December 2000 and since then we have refitted all but one of within the next three years. Obviously this will continue to cause some the 18 stores in this category in our portfolio, including stores in London, disturbance to our normal trading patterns and sales performance in the Leeds, Aberdeen and Glasgow. -

Competition (Amendment) Act 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction p.4 2. The Groceries Order - Legal Background p.7 3. The Fair Trade Commission Report 1991 p.17 4. Summary of Submissions on the Groceries Order p.20 5. Independent Study on Impact of the Groceries Order p.34 6. Arguments in favour of retaining the Groceries Order p.39 7. Arguments against retaining the Groceries Order p.77 8. Conclusion and Proposals p.95 Appendix A Report of DKM Economic Consultants Limited entitled “Economic Impact on the 1987 Groceries Order”. 1 FOREWORD One of the faintly bizarre aspects of the public policy debate on competition law is the passion aroused by the only left-over remnant of the old Restrictive Practices regime, namely the Groceries Order. Its best known feature is the ban on below invoice price selling (commonly, if somewhat inaccurately, referred to as 'below-cost-selling') and it is this feature which arouses the most controversy. However, as highlighted in particular in Chapter 6 within, some of the other provisions of the Groceries Order (such as those relating to suppliers’ terms and conditions and the ban on “hello” money, sometimes referred to as “fair trade” provisions) are also capable of generating controversy. A further peculiarity of the debate on the Groceries Order is that its legal status is such that it cannot be amended. It can only be either left intact or repealed in its entirety. As explained in Chapter 2 within, this is because the order was made under the Restrictive Practices legislation which was repealed by the Competition Act 1991. -

Evidence from UK Food Retailing De Ce O U Ood Eta G

Do SSlales MMtt?atter? Eviden ce fr om UK F ood R etailing Tim Lloyd , Wyn Morgan, Steve McCorriston and Evious Zgovu Paper prepared for the INRA-IDEI Semi nar, “Competiti on and Strat egi ies in the Ret aili ng Ind ust ry” , Toulouse School of Economics, 16/17 May 2011. Funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 265601 is gratefully acknowledged. The results reflect the views of the authors only. Motivation and Aims Supermarkets have come to dominate the retail landscape A distinctive feature of supermarket prices is the prominent use of discounting (‘sales’) in price variation Variation in food prices is important at two levels: Macro-economic: . Retail price inflation Microeconom ic: . Sales as a competitive tool in imperfectly competitive markets Nielsen Scantrack© : scanner dataset of 230,000 prices Literature Literature on retail price dynamics: . relatively recent and growing with the availability of new microdata sources (Maćkowiak and Smets 2008, Dhyne et al. 2006) . empirical evidence does not sit easily with standard theory (Nakamura and Steinsson 2008, Berck et al. 2008) . emphasises the role of retailer (not manufacturer) in price setting (Chevalier et al. 2003, Nakamura 2008,) . downplays cost shocks as principal source of variation (Nakamura 2008) . importance of sales in price variability (20-50%) (Pesendorfer 2000, Hosken and Reiffen 2004, Berck et al. 2008, Naaakamu uaadra and Steinsso n2008) Heterogeneity a recurrent theme Contribution We focus on sales in retail price dynamics in food sector, relatively few studies, particularly in EU . Are sales less important in EU than US? .