PTA Guidance August 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for Unrepresented Claimants in Upper Tribunal Immigration And

THE HON MRJUSTICE BLAKE PRESIDENT OF THE UPPER TRIBUNAL, IMMIGRATION AND ASYLUM CHAMBER Presidential Guidance Note 2013 No 3: GUIDE FOR UNREPRESENTED CLAIMANTS IN THE UPPER TRIBUNAL IMMIGRATION AND ASYLUM CHAMBER SEPTEMBER 2013 1 Contents Foreword p.3 1. Introduction: key points to bear in mind p.4-5 2. Applying to the First-tier Tribunal for Permission to Appeal to the p.6-7 Upper Tribunal 3. Re-applying to the Upper Tribunal for Permission to Appeal p.8-9 4. What happens after permission to appeal has been granted p.10-12 5. The appeal hearing p.13-16 6. Sponsor as Representative p.17 7. “McKenzie friend” p.18 8. Application to the Court of Appeal for Permission to Appeal p.19-21 Words and Phrases used in the Upper Tribunal p.22-24 Appendix One- Form IA FT4 p.25-28 Appendix Two- Form IAUT-1 p.29-35 Appendix Three-Form N161 & Form 40.2 p.36-46 Appendix Four-Practical Guidance “McKenzie Friends” p.47-53 Appendix Five-Practice Statements Immigration and Asylum Chambers of p.54-64 the First-tier Tribunal and the Upper Tribunal Appendix Six- Sample Directions p.65-69 2 Foreword All courts and tribunals throughout the country recognise the rights of the parties to represent themselves in a case that involves them. We are aware that a person may be unfamiliar with the procedures and this Guide is designed to help them. The Guide1 deals solely with the procedures of the Immigration and Asylum Chamber of the Upper Tribunal for appeals from the First-tier Tribunal. -

Ministry of Justice Letterhead

The Right Honourable Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor & Secretary of State for Justice Sir Bob Neill MP Chair of the Justice Committee House of Commons MoJ Ref: 86346 SW1A 0AA 17 March 2021 Dear Bob, INDEPENDENT REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW I am writing to let you and your Committee know that the Independent Review of Administrative Law has now concluded its work and the Panel’s report has been submitted to Ministers. Despite the circumstances under which the Panel worked, with the majority of their discussions having to take place virtually, they have produced an excellent, comprehensive report. I believe it goes much further than previous reviews in the use of empirical evidence and in consideration of some of the wider issues of Judicial Review, such as the evolving approach to justiciability and the arguments for and against codification. The Panel set out a number of recommendations for reform which the Government has considered carefully. I agree with the Panel’s analysis and am minded to take their recommendations forward. However, I feel that the analysis in the report supports consideration of additional policy options to more fully address the issues they identified. Therefore, I will very shortly be launching a consultation on a range of options which I want to explore before any final policy decisions are made. The IRAL call for evidence elicited many helpful submissions on Judicial Review and we are not seeking to repeat that exercise. Rather, we want consultees to focus on the measures in the consultation document. They set out our full range of thinking, which is still at an early stage, and respondents’ contributions to the consultation will help us decide which of the options to take forward. -

Bill Written Submission from Douglas J May QC And

T1 Justice Committee Tribunals (Scotland) Bill Written submission from Douglas J May QC and Allan J Gamble 1. We are salaried judges of the Upper Tribunal, Administrative Appeals Chamber, sitting in Scotland. Our Chamber is presided over by Mr Justice Charles. There are salaried judges in England and Wales and Northern Ireland as well as ourselves. We hold permanent Crown appointments. In both Scotland and England and Wales there are a number of fee paid judges who hold tenure on five year appointments. The Chamber hears appeals from the following First-tier Chambers namely Social Entitlement, Health Education and Social Care, General Regulatory, Armed Forces Pensions and also from the Pensions Appeal Tribunal in Scotland, which is devolved, but appeals are heard by our Chamber of the Upper Tribunal. In addition we hear appeals from the Traffic Commissioners. We have accepted the invitation for one of us to present oral evidence to the Committee. However, we are presenting this written evidence setting out the principal issues we would wish to bring to the attention of the Committee. 2. We consider that the proposed new system for devolved tribunals in Scotland to be an improvement on the existing arrangements. We are fortified in that view by our own experience of the implementation of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 which has brought consistency and coherence to administrative justice on both reserved jurisdictions and those relating exclusively to England and Wales such as the Health Education and Social Care jurisdictions. We do however note that the scope and extent of the devolved jurisdictions to be transferred in is more restrictive than originally contemplated. -

IN the UPPER TRIBUNAL Case No

R.(Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority) v First-tier Tribunal (CIC) [2018] UKUT 439 (AAC) IN THE UPPER TRIBUNAL Case No. JR/906/2017 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Lady Carmichael Upper Tribunal Judge Rowland Upper Tribunal Judge Markus QC Mr Chris Pirie (of the Scots Bar), instructed by Ms Eileen Grant of the Authority’s Legal and Policy Team, appeared for the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority. The First-tier Tribunal did not appear and was not represented. Ms Clare Connolly (of the Scots Bar), instructed by Ms Dominika Schmidtova of Thompsons solicitors, appeared for the injured person. Decision: This application for judicial review is struck out on the ground that the Upper Tribunal does not have jurisdiction because, even if the Upper Tribunal has jurisdiction in the strict sense, it declines to exercise it. REASONS FOR DECISION 1. This is an application, made by the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority (“the Authority”) with permission granted by Upper Tribunal Judge Markus QC, for judicial review of a decision of the First-tier Tribunal dated 15 December 2016, whereby it allowed an appeal brought by the Interested Party (the “injured person”) against a review decision of the Authority dated 23 February 2016. 2. The Authority had decided that the injured person was not entitled to compensation under the Criminal Injuries Compensation Scheme 2012 (“the 2012 Scheme”) because he had not suffered an injury described in the tariff at Annex E to the Scheme. The First-tier Tribunal decided that he had suffered such an injury. The Authority considers that that decision was made in error of law. -

IN the HIGH COURT of JUSTICE Claim No. CO/2368/2016 QUEEN's BENCH DIVISION DIVISIONAL COURT BETWEEN

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim No. CO/2368/2016 QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION DIVISIONAL COURT B E T W E E N: THE QUEEN on the application of PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL Claimant -and- INVESTIGATORY POWERS TRIBUNAL Defendant -and- (1) SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS (2) GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATIONS HEADQUARTERS Interested Parties —————————————————————————————————— CLAIMANT’S SKELETON ARGUMENT ON PRELIMINARY ISSUE For hearing: 2 November 2016, 1 day —————————————————————————————————— A. Introduction 1. The preliminary issue raises an important question of law: is a decision of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal amenable to judicial review? Does the ‘ouster clause’ in section 67(8) of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (“RIPA”) prevent the High Court from correcting an error of law made by the IPT? 2. A decision of the IPT is amenable to judicial review. Applying the principles in Anisminic v Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147, the ouster clause does not prevent judicial review of a decision of the Tribunal where it errs in law. 3. Lang J concluded that the Claimant had (a) an arguable case that the IPT had got the law wrong; and (b) granted a Protective Costs Order. If the Court has no jurisdiction to hear this claim, a significant error of law may go uncorrected. 1 B. The IPT proceedings and the substantive claim for judicial review 4. The claim before the IPT was about the hacking of computers, including mobile devices and network infrastructure (known within the security and intelligence services as ‘CNE’ - computer and network exploitation). 5. The potential intrusiveness of CNE, as illustrated by what could be accessed by hacking a mobile phone, was summarised by Chief Justice Roberts in Riley v California in the Supreme Court of the United States: “A cell phone search would typically expose to the government far more than the most exhaustive search of a house…” As Roberts CJ explained: “Cell phones differ in both a quantitative and a qualitative sense from other objects that might be kept on an arrestee’s person. -

Ousting Ouster Clauses: the Ins and Outs of the Principles Regulating the Scope of Judicial Review in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2020] 392–426 OUSTING OUSTER CLAUSES: THE INS AND OUTS OF THE PRINCIPLES REGULATING THE SCOPE OF JUDICIAL REVIEW IN SINGAPORE Thio Li-ann∗ How a court responds to an ouster clause or other attempts to curb its jurisdiction, which seeks to exclude or limit judicial review over a public law dispute, is a reflection of the judicial perception of its role within a specific constitutional order. Article 4 of the Singapore Constitution declares the supremacy of constitutional law over all other forms of law—whether statutory, common law or customary in origin. The courts have judicially declared various unwritten constitutional principles which are of particular relevance to the question of the scope of judicial review, particularly, the separation of powers and the rule of law. With comparative references where illuminating, this article examines the scope of judicial review in Singapore administrative law, in the face of legislative intent that it be partially truncated or wholly excluded, with a view to identifying and evaluating the factors that have been judicially considered relevant in ascertaining the legitimacy of an ouster clause, including the Article 93 judicial power clauses and the inter-play of other constitutional principles. I. Introduction: Legislative Intervention in the Realm of Judicial Review The law on ouster clauses, which shapes the scope of judicial review, may be seen as “a theatre of legislative-judicial engagement,”1 revealing how institutional actors view their role within a constitutional order, and the nature of administrative law within that polity. Courts have traditionally been hostile towards statutory attempts to exclude or restrict their supervisory jurisdiction, a facet of their general and inherent powers of adjudication, over jurisdictional excesses. -

Carnwath IRAL Response 27.4.21

Carnwath IRAL response 27.4.21 JUDICIAL REVIEW REFORM - THE GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO THE INDEPENDENT REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW Response to Consultation by Lord Carnwath CVO1 Introduction 1. The Faulks panel are to be congratulated for completing, in a remarkably short time, and after wide-ranging consultation, a thorough and objective account of the modern practice of judicial review. I generally welcome their findings and their main recommendation, which accord in many respects with my own lecture to the Bar Reform Group in December 2020.2 I also welcome the response paper in so far as it adopts their proposals. 2. To the extent that it pursues ideas for law reform going beyond those recommended or identified by the panel, it is much more questionable. If the Lord Chancellor has serious practical concerns on law reform issues 1 Former Justice of the UK Supreme Court (2012-2020), Chairman of the Law Commission for Englnad and Wales (1998-2001), and Senior President of Tribunals (2005-2012); Associate of Landmark Chambers. I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr Joanna Bell, Associate Professor, Oxford University Faculty of Law. 2 Now available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/SSDESSXSQRZNYETUZZQD/full?target=10.1080/10854681.2020.1 871713 Page 1 Carnwath IRAL response 27.4.21 not adequately addressed by the Faulks review, then the obvious course is to refer them to the Law Commission, which (unlike the Ministry) has the independence, authority and legal expertise to carry out a proper study and propose appropriate solutions. 3. In the remainder of this submission I will attempt to address the points of significance in the response paper. -

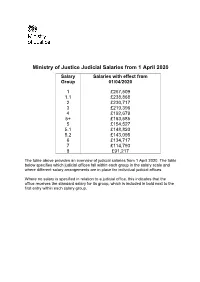

Ministry of Justice Judicial Salaries from 1 April 2020 Salary Salaries with Effect from Group 01/04/2020

Ministry of Justice Judicial Salaries from 1 April 2020 Salary Salaries with effect from Group 01/04/2020 1 £267,509 1.1 £238,868 2 £230,717 3 £219,396 4 £192,679 5+ £163,585 5 £154,527 5.1 £148,820 5.2 £143,095 6 £134,717 7 £114,793 8 £91,217 The table above provides an overview of judicial salaries from 1 April 2020. The table below specifies which judicial offices fall within each group in the salary scale and where different salary arrangements are in place for individual judicial offices. Where no salary is specified in relation to a judicial office, this indicates that the office receives the standard salary for its group, which is included in bold next to the first entry within each salary group. Judge Title and Salary Group Includes Salaries Salaries Salaries w.e.f. w.e.f w.e.f 01/04/19 01/10/19 01/04/20 Salary Group 1 262,264 262,264 267,509 Lord Chief Justice Salary Group 1.1 234,184 234,184 238,868 Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland Lord President of the Court of Session (Scotland) Master of the Rolls President of the Supreme Court Salary Group 2 226,193 226,193 230,717 Chancellor of the High Court Deputy President of the Supreme Court Justices of the Supreme Court Lord Justice Clerk (Scotland) President of the Family Division President of the Queen’s Bench Division Senior President of Tribunals Salary Group 3 215,094 215,094 219,396 Inner House Judges of the Court • President of Scottish of Session (Scotland) Tribunals Lords/Lady Justices of Appeal • Senior Presiding Judge • Deputy Senior Presiding Judge • Deputy Head -

Appealing to the Administrative Appeals Chamber of the Upper Tribunal

UT11 Notes Appealing to the Administrative Appeals Chamber of the Upper Tribunal Against decisions of the First-tier Tribunal (General Regulatory Chamber) (but not Information Rights cases) Including: Claims Management Services Food Regulation Community Right to Bid Gambling Consumer Credit Immigration Services Environment Professional Regulation Estate Agents Transport Exam Boards Contents Introduction 2 What is the Administrative Appeals Chamber of the Upper Tribunal? 2 Which parts of the United kingdom have jurisdiction? 3 Where are the offices of the Administrative Appeals Chamber of the Upper Tribunal? 4 Who can appeal to the Upper Tribunal? 5 Before you can appeal 5 Reasons (grounds) for appealing 5 How to Appeal 6 What happens once permission has been granted? 8 Oral Hearings 9 The decision of the Upper Tribunal on the appeal 10 Particular issues which may arise on appeals 11 What to do if you are dissatisfied with the decisions of the Upper Tribunal 11 The Meaning of Words 12 General Note 14 UT11 Notes - Notes for Form UT11 (Against decisions of the First-tier Tribunal (General Regulatory Chamber) (09.15) © Crown copyright 2015 Page 1 Introduction About this leaflet This leaflet is to help both members of the public and advisors. It describes what steps you need to take to appeal to the Administrative Appeals Chamber of the Upper Tribunal, against a decision given by the General Regulatory Chamber of the First-tier Tribunal, once you have asked the First-tier Tribunal judge for permission to appeal. It explains what will happen to an appeal, in the Administrative Appeals Chamber of the Upper Tribunal, once it has been made. -

Judicial Review Reform the Government Response to the Independent Review of Administrative Law

Judicial Review Reform The Government Response to the Independent Review of Administrative Law Date of publication: March 2021 CP 408 Judicial Review Reform The Government Response to the Independent Review of Administrative Law Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty March 2021 CP 408 © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-2477-0 CCS0321152500 03/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office About this consultation Duration: 18/03/21 to 29/04/2021 Enquiries (including Judicial Review Reform requests for the paper in an Ministry of Justice alternative format) to: 102 Petty France London SW1H 9AJ Email: [email protected] How to respond: Please send your response by 29/04/2021 by using the online portal: https://consult.justice.gov.uk/judicial-review- reform/judicial-review-proposals-for-reform By mail to: Judicial Review Reform Ministry of Justice 102 Petty France London SW1H 9AJ Or by email to [email protected] Additional ways to feed in A series of webinars is also taking place. -

Ouster Clauses and National Security: Judicial Review of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal

Scott, P. F. (2017) Ouster clauses and national security: judicial review of the investigatory powers tribunal. Public Law, 2017(3), pp. 355-362. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/137525/ Deposited on: 29 March 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Ouster Clauses and National Security: Judicial Review of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal Paul F Scott* 1. Introduction One of the principles most dear to the United Kingdom’s constitution is the rule of law, at the core of which stand the requirement that the state abide by law and – a necessary corollary of that – the right of individuals to challenge the lawfulness of the acts of public decision-makers by invoking the supervisory jurisdiction. This commitment to the rule of law manifests itself in particular in a deep suspicion of ‘ouster clauses’ by which statutes purport to limit or exclude the exercise of the supervisory jurisdiction. In R (Privacy International) v Investigatory Powers Tribunal,1 the High Court has held that the ouster clause in the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 – the statute which creates the Investigatory Powers Tribunal – suffices to prevent the High Court from carrying out judicial review of that tribunal’s decisions. This decision is unusual in recognising that an ouster clause has that effect. It is also, I argue here, incorrect. Though the creation, by the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, 2 of a limited right to appeal against decisions of the IPT will limit the implications of this failure to insist upon the rule of law ideal, the constitutional significance of the matter is such that this wrong should be put right at the first available opportunity. -

Senior President of Tribunals' Annual Report

Senior President of Tribunals’ Annual Report 2019 Senior President of Tribunals’ Annual Report 2019 Contents Contents Introduction 4 Tribunals’ Structure Chart 12 Annex A - Upper Tribunal 13 Administrative Appeals Chamber - President: Dame Judith Farbey 13 Tax and Chancery Chamber - President: Sir Anthony (Tony) Zacaroli 17 Immigration and Asylum Chamber - President: Sir Peter Lane 19 Lands Chamber - President: Sir David Holgate 20 Annex B - First-tier Tribunal 25 Social Entitlement Chamber - President: Judge John Aitken 25 Health, Education and Social Care Chamber (HESC) - President: His Honour Judge Phillip Sycamore 32 War Pensions and Armed Forces Compensation Chamber (WPAFCC) - Acting President: Judge Sehba Storey 35 Tax Chamber - President: Judge Greg Sinfield 38 General Regulatory Chamber (GRC) - President: Judge Alison McKenna 43 Immigration and Asylum Chamber (IAC) - President: Judge Michael Clements 44 Property Chamber - President: Judge Siobhan McGrath 47 Annex C - Employment 53 Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) - President: Sir Akhlaq Choudhury 53 Employment Tribunal (England & Wales) - President: Employment Judge Brian Doyle 56 Employment Tribunals (Scotland) - President: Employment Judge Shona Simon 62 Annex D - Cross Border Issues 66 Northern Ireland - Dr Kenneth Mullan 66 Scotland - Sir Brian Langstaff 66 Annex E - Reform in the Upper Tribunal and Employment Appeal Tribunal 68 Senior President of Tribunals’ response 69 Annex F - Reform in the First-tier Tribunal and Employment Tribunals 70 Senior President of Tribunals’ response 71 Annex G - Important Cases 72 3 Senior President of Tribunals’ Annual Report 2019 SPT’s Report Introduction By the Senior President of Tribunals, The Rt Hon Sir Ernest Ryder It is now four years since my appointment as Senior President.