Nber Working Paper Series When Did Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of the Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies

After the Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of the Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies By KARLA HOFF AND JOSEPH E. STIGLITZ* In recent years economists have increasingly [Such] institutions would follow private been concerned with understanding the creation property rather than the other way around of the “rules of the game”—in the broad sense (pp. 10–11). of political economy—rather than merely the behaviors of agents within a set of rules already But there was no theory to explain how this in place. The transition from plan to market of process of institutional evolution would occur the countries in the former Soviet bloc entailed and, in fact, it has not yet occurred in Russia and an experiment in creating new rules of the many of the other transition economies. A cen- game. In going from a command economy, tral reason for that, according to many scholars, is the weakness of the political demand for the where almost all property is owned by the state, 1 to a market economy, where individuals control rule of law. As Bernard Black et al. (2000) their own property, an entirely new set of insti- observe for Russia, tutions would need to be established in a short period. How could this be done? company managers and kleptocrats op- The strategy adopted in Russia and many posed efforts to strengthen or enforce the capital market laws. They didn’t want a other transition economies was the “Big strong Securities Commission or tighter Bang”—mass privatization of state enterprises rules on self-dealing transactions. -

Transnational Corporations Investment and Development

Volume 27 • 2020 • Number 2 TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS INVESTMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Volume 27 • 2020 • Number 2 TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS INVESTMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Geneva, 2020 ii TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS Volume 27, 2020, Number 2 © 2020, United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licences, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications 405 East 42nd Street New York New York 10017 United States of America Email: [email protected] Website: un.org/publications The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has been edited externally. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/DIAE/IA/2020/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales no.: ETN272 ISBN: 978-92-1-1129946 eISBN: 978-92-1-0052887 ISSN: 1014-9562 eISSN: 2076-099X Editorial Board iii EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief James X. Zhan, UNCTAD Deputy Editors Richard Bolwijn, UNCTAD -

Globalization and Infectious Diseases: a Review of the Linkages

TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 SPECIAL TOPICS NO.3 Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages Social, Economic and Behavioural (SEB) Research UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) The "Special Topics in Social, Economic and Behavioural (SEB) Research" series are peer-reviewed publications commissioned by the TDR Steering Committee for Social, Economic and Behavioural Research. For further information please contact: Dr Johannes Sommerfeld Manager Steering Committee for Social, Economic and Behavioural Research (SEB) UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) World Health Organization 20, Avenue Appia CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages Lance Saker,1 MSc MRCP Kelley Lee,1 MPA, MA, D.Phil. Barbara Cannito,1 MSc Anna Gilmore,2 MBBS, DTM&H, MSc, MFPHM Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum,1 D.Phil. 1 Centre on Global Change and Health London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK 2 European Centre on Health of Societies in Transition (ECOHOST) London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 Copyright © World Health Organization on behalf of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases 2004 All rights reserved. The use of content from this health information product for all non-commercial education, training and information purposes is encouraged, including translation, quotation and reproduction, in any medium, but the content must not be changed and full acknowledgement of the source must be clearly stated. -

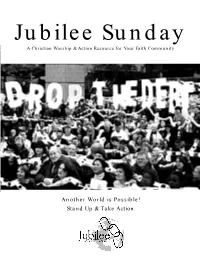

Another World Is Possible! Stand up & Take Action

Jubilee Sunday A Christian Worship & Action Resource for Your Faith Community Another World is Possible! Stand Up & Take Action Contents Letter from Our Executive Director...................................................... 1 Worship Resources.................................................................................... 2 Jubilee Vision....................................................................................... 2 Minute for Mission.............................................................................. 4 Prayers of Intercession for Jubilee Sunday.................................... 6 Hymn Suggestions for Worship........................................................ 7 Jubilee Sunday Sermon Notes........................................................... 9 Children’s Sermon............................................................................... 10 Children and Teen Sunday School Activities................................. 11 Jubilee Action – Another World is Possible....................................... 13 Stand Up Pledge.......................................................................................... 14 Dear partners for a real Jubilee, Thank you for participating in our annual Jubilee Sunday -- your participation in this time will help empower our leaders in the United States to take action for the world’s poorest. Join Jubilee Congregations around the United States on October 14, 2012 to pray for global economic justice, to deepen your community’s understanding of the debt issue, take decisive -

World Economy and Globalization

World economy and globalization Project „Joint Degree Study programme “Technology and Innovation Management“ No. VP1-2.2-ŠMM-07-K-02-087 Aim of the course unit is to (1/1): 1. Give insight on the process of globalisation, its characteristics as well as causes and effects on world economy; the role of corporations, NGOs, governments and multilateral institutions in shaping world economy; Aim of the course unit is to (1/2): 2. Build knowledge of students in the current state of world economies with focus on major economies of the world; the nature of world financial markets; economic implications in terms of national economic development and inequality; Aim of the course unit is to (1/3): 3. Develop skills of students in analysis of economic charaxteristics of globalization and increased trade flow; analysis of economic inequality impacts and effects. The main topics 1. Theories of globalization. Economic globalization 2. Globalization characteristics 3. Globalization – causes and effects on world economy 4. Government and the multinational corporations 5. Economic implications – development 6. Economic implications – inequality 7. Financial markets 8. Multilateral organizations 9. The Triad and the BRICs The introduction to the course The core essence of globalization is often misunderstood because the process of globalisation is confusing due to its multifaceted nature and oftentimes it is being confused with other processes and misinterpreted. Apart from the complexity of the process of globalization itself, it is important to point out that the word “globalization” entered a dictionary (of American English) in 1961 [by the reference of, which is only almost half a century ago. -

The Negros to Serve Forever: the Evolution of Black's Life and Labor in Seventeenth-Century Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 The Negros to Serve Forever: The Evolution of Black's Life and Labor in Seventeenth-Century Virginia Laura Croghan Kamoie College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kamoie, Laura Croghan, "The Negros to Serve Forever: The Evolution of Black's Life and Labor in Seventeenth-Century Virginia" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625919. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-erp9-a557 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "The Negroes to Serve Forever": The Evolution of Blacks' Life and Labor in Seventeenth-Century Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Laura A. Croghan 1994 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts A. Croghanau: Approved, November 1994 James Axtell ii This volume is dedicated to my mother, Ann Croghan,for all of her patient support of my seemingly endless years in school; and to my best friend, Brian Kamoie,for showing me all the joys of love and friendship. -

History of Global Economy

HISTORY OF GLOBAL ECONOMY We begin our discussion of the history of the global economy with the following question. What has led to such strong differences across regions of the world? The quick and dirty answer is simply that the "West" developed first. Birth of Capitalism1 One can find examples of sustained economic growth throughout history, for example in the woolen industry in 13th century Flanders, and in 14th century Florence. Starting with the 11th century long distance trading flourished connecting thriving pockets of growth, between Venice and the Netherlands. However, by and large, living standards remained at subsistence levels for the majority of the world's population until the middle of the 18th century. Over the centuries as commerce grew, albeit slowly, the power of the vassals of the feudal system declined being replaced by merchants and incipient capitalists. Innovations in sailing led to long distance trading. The opportunities and challenges of sending a vessel abroad for years at a time brought about the institutions which facilitated the growth of the modern capitalist system. Institutions which spurred the growth of capitalism Principle of Private Property Joint Stock Companies Deposit Banking Insurance Formal Contracts International Financial Markets Craft Guilds Government Support of Opening Markets Merchant Associations At the same time burgeoning industrialization and urbanization further weakened the feudal economy changing both the political as well as the economic structure of Europe. The question remains why in the “west”? Some of the factors contributing to these changes were: 1) The Protestant Reformation - note that industrialization began in northern Europe. Protestant work ethic - fostered hard work, frugality, sobriety and efficiency, virtues which facilitated capitalism. -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

Globalization: a Short History

CHAPTER 5 GLOBALIZATIONS )URGEN OSTERHAMMEL TI-IE revival of world history towards the end of the twentieth century was intimately connected with the rise of a new master concept in the social sciences: 'globalization.' Historians and social scientists responded to the same generational experience·---·the impression, shared by intellectuals and many other people round the world, that the interconnectedness of social life on the planet had arrived at a new level of intensity. The world seemed to be a 'smaller' place in the 1990s than it had been a quarter century before. The conclusions drawn from this insight in the various academic disciplines, however, diverged considerably. The early theorists of globalization in sociology, political science, and economics disdained a historical perspective. The new concept seemed ideally suited to grasp the characteristic features of contemporary society. It helped to pinpoint the very essence of present-day modernity. Historians, on their part, were less reluctant to envisage a new kind of conceptual partnership. An earlier meeting of world history and sociology had taken place under the auspices of 'world-system theory.' Since that theory came along with a good deal of formalisms and strong assumptions, few historians went so far as to embrace it wholeheartedly. The idiom of 'globalization,' by contrast, made fewer specific demands, left more room for individuality and innovation and seemed to avoid the dogmatic pitfalls that surrounded world-system theory. 'Globalization' looked like a godsend for world historians. It opened up a way towards the social science mainstream, provided elements of a fresh terminology to a field that had sutlcred for a long time from an excess of descriptive simplicity, and even spawned the emergence of a special and up""ttHlate variant of world history-'global history.' Yet this story sounds too good to be true. -

A Read of at the Back of the North Wind

A Read��� of At the Back of the North Wind Col�� Ma�love acDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind (1871) was first serialised inM Good Words for the Young under his own editorship, from October 1868 to November 1870. It was his first attempt at writing a full-length “fairy-story” for children, following on his shorter fairy tales—including “The Selfish Giant,” “The Light Princess,” and “The Golden Key”—written between 1862 and 1867, and published in Dealings with the Fairies (1867). At the Back of the North Wind is, in fact, longer than either of the Princess books that were to follow it, The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and The Princess and Curdie (1882). It tells of the boy Diamond’s life as a cabman’s son in a poor area of mid-Victorian London, and of his meetings and adventures with a lady called North Wind; and it includes a separate fairy tale called “Little Daylight,” two dream-stories, and several poems. Generally well received by the public, it has hardly been out of print since. At the Back of the North Wind is MacDonald’s only fantasy set mainly in this world. In Phantastes (1858), Anodos goes into Fairy Land and in Lilith Mr. Vane finds himself in the Region of the Seven Dimensions. In the Princess books we are in a fairy-tale realm of kings, princesses, and goblins; and the worlds of the shorter fairy tales are all full of fairies, witches, and giants. But Diamond’s story nearly all happens either in Victorian London or in other parts of the world where North Wind takes him. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes.