30 Years of Rhodes Women, Which Includes This Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miljø- Og Fødevareudvalget 2016-17 MOF Alm.Del Endeligt Svar På Spørgsmål 892 Offentligt

Miljø- og Fødevareudvalget 2016-17 MOF Alm.del endeligt svar på spørgsmål 892 Offentligt Til: [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] (kloepper@waddensea- secretariat.org), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] ([email protected]), [email protected] -

'Ways of Seeing': the Tasmanian Landscape in Literature

THE TERRITORY OF TRUTH and ‘WAYS OF SEEING’: THE TASMANIAN LANDSCAPE IN LITERATURE ANNA DONALD (19449666) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (English and Cultural Studies) 2013 ii iii ABSTRACT The Territory of Truth examines the ‘need for place’ in humans and the roads by which people travel to find or construct that place, suggesting also what may happen to those who do not find a ‘place’. The novel shares a concern with the function of landscape and place in relation to concepts of identity and belonging: it considers the forces at work upon an individual when they move through differing landscapes and what it might be about those landscapes which attracts or repels. The novel explores interior feelings such as loss, loneliness, and fulfilment, and the ways in which identity is derived from personal, especially familial, relationships Set in Tasmania and Britain, the novel is narrated as a ‘voice play’ in which each character speaks from their ‘way of seeing’, their ‘truth’. This form of narrative was chosen because of the way stories, often those told to us, find a place in our memory: being part of the oral narrative of family, they affect our sense of self and our identity. The Territory of Truth suggests that identity is linked to a sense of self- worth and a belief that one ‘fits’ in to society. The characters demonstrate the ‘four ways of seeing’ as discussed in the exegesis. ‘“Ways of Seeing”: The Tasmanian Landscape in Literature’ considers the way humans identify with ‘place’, drawing on the ideas and theories of critics and commentators such as Edward Relph, Yi-fu Tuan, Roslynn Haynes, Richard Rossiter, Bruce Bennett, and Graham Huggan. -

Democratising the IMF: Involving Parliamentarians

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Eggers, Andrew C.; Florini, Ann M.; Woods, Ngaire Working Paper Democratising the IMF: Involving parliamentarians GEG Working Paper, No. 2005/20 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Oxford, Global Economic Governance Programme (GEG) Suggested Citation: Eggers, Andrew C.; Florini, Ann M.; Woods, Ngaire (2005) : Democratising the IMF: Involving parliamentarians, GEG Working Paper, No. 2005/20, University of Oxford, Global Economic Governance Programme (GEG), Oxford This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196283 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu • GLOBAL ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE PROGRAMME • Andrew Eggers, Ann Florini and Ngaire Woods. GEG Working Paper 2005/20 Andrew Eggers Andrew Eggers is currently a PhD candidate in Government at Harvard University. -

Information for Candidates for The

USA THE RHODES SCHOLARSHIP FOR UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Covering the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES - for selection for 2022 only (This Memorandum cancels those issued for previous years) Background Information The Rhodes Scholarships, established in 1903, are the oldest international scholarship programme in the world, and one of the most prestigious. Administered by the Rhodes Trust in Oxford, the programme offers 100 fully-funded Scholarships each year for postgraduate study at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom - one of the world’s leading universities. Rhodes Scholarships are for young leaders of outstanding intellect and character who are motivated to engage with global challenges, committed to the service of others and show promise of becoming value-driven, principled leaders for the world’s future. The broad selection criteria are: Academic excellence – specific academic requirements can be found under ‘Eligibility Criteria’ below. Energy to use your talents to the full (as demonstrated by mastery in areas such as sports, music, debate, dance, theatre, and artistic pursuits, including where teamwork is involved). Truth, courage, devotion to duty, sympathy for and protection of the weak, kindliness, unselfishness and fellowship. Moral force of character and instincts to lead, and to take an interest in your fellow human beings. Please see the Scholarships area of the Rhodes Trust website for full details: www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk Given the current situation with the Covid-19 pandemic, aspects of the application requirements and subsequent selection processes may be subject to change. Our website and this document will be updated with any changes, and once you have started an application any changes will be communicated via email. -

Mathematics People

Mathematics People Mathematics Student Wins physicists might apply to help understand the fundamen- tal forces of nature: electricity, magnetism, and gravity. Siemens Competition “Mr. Vaintrob found a very beautiful formula for de- scribing the way shapes combine in string theory,” said For the second straight year, a high school mathematician competition judge Michael Hopkins of Harvard Universi- has won the grand prize in the Siemens Competition in ty. “His work is at the Ph.D. level, publishable and already Math, Science, and Technology. The top honors for the attracting the attention of researchers.” 2006–2007 competition went to Dmitry Vaintrob, a Vaintrob was introduced to this topic of research by senior at South Eugene High School in Eugene, Oregon. He his mentor, Pavel Etingof of the Massachusetts Institute won a US$100,000 scholarship in the individual category. of Technology, who proposed a problem that came out of Vaintrob’s project, “The String Topology BV Algebra, his own recent work. “It was an insanely difficult problem, Hochschild Cohomology, and the Goldman Bracket on Sur- which he solved within weeks and then came up with an faces”, involves the new mathematical field of string topol- important additional development,” said Hopkins. “This ogy. Focusing on mathematical shapes, his work offers in- brilliant young mathematician showed amazing maturity sights that are universal and applicable in any field. His re- and perspective which would be surprising in a graduate search could provide knowledge that mathematicians and student, let alone a high school senior.” Vaintrob is a volunteer in his high school library and in themathematicslibraryattheUniversityofOregon.Healso organized the math club in his high school. -

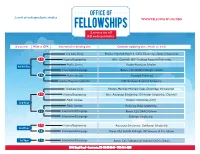

Fellowships Flowchart FA17

A unit of undergraduate studies WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU A service for all KU undergraduates If you are: With a GPA: Interested in funding for: Consider applying for: (details on back) Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Soros, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Churchill, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Public Service Knight-Hennessy Scholars 4th/5th Year International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright, Gilman 3.2+ Public Service Carnegie, Pickering Science/Engineering/SocSci NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship, Churchill Public Service Truman Scholarship (3.5+) 3rd Year Public Service Pickering, Udall Scholarship 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman International/Language Fulbright Scholarship 3.7+ Science/Engineering Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship 2nd Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1st Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1506 Engel Road • Lawrence, KS 66045-3845 • 785-864-4225 KU National Fellowship Advisors ✪ Michele Arellano Office of Study Abroad WE GUIDE STUDENTS through the process of applying for nationally and internationally Boren and Gilman competitve fellowships and scholarships. Starting with information sessions, workshops and early drafts [email protected] of essays, through application submission and interview preparation, we are here to help you succeed. ❖ Rachel Johnson Office of International Programs Fulbright Programs WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU [email protected] Knight-Hennessy Scholars: Full funding for graduate study at Stanford University. ★ Anne Wallen Office of Fellowships Applicants should demonstrate leadership, civic commitment, and want to join a Campus coordinator for ★ awards. -

Ngaire Woods, GEG Working Paper 2004/01

• GLOBAL ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE PROGRAMME • Ngaire Woods, GEG Working Paper 2004/01 Ngaire Woods Ngaire Woods is Director of the Global Economic Governance Programme at University College, Oxford. Her most recent book The Globalizers is being published by Cornell University Press. She has previously published The Political Economy of Globalization (Macmillan, 2000), Inequality, Globalization and World Politics (with Andrew Hurrell: Oxford University Press, 1999), Explaining International Relations since 1945 (Oxford University Press, 1986), and numerous articles on international institutions, globalization, and governance. Ngaire Woods is an Adviser to the UNDP's Human Development Report, a member of the Helsinki Process on global governance and of the resource group of the UN Secretary-General's High-Level Commission into Threats, Challenges and Change. She was a member of the Commonwealth Secretariat Expert Group on Democracy and Development established in 2002, which reported in 2004. 1 Ngaire Woods, GEG Working Paper 2004/01 Introduction In 1997 a crash in the Thai baht caused a financial crisis, which rapidly spread across East Asia and beyond. Many countries were affected by the crisis. Some immediately, and others less directly as the reversal in confidence in emerging markets spread across to other corners of the globe. It soon became apparent that the East Asian crisis had recalibrated the willingness of capital markets to invest in emerging markets. A new kind of financial crisis had been borne. The financial crises of the 1990s sparked debate about the causes of financial crises and how best to manage them.1 The IMF soon found itself criticized on several counts. -

Willis Papers INTRODUCTION Working

Willis Papers INTRODUCTION Working papers of the architect and architectural historian, Dr. Peter Willis (b. 1933). Approx. 9 metres (52 boxes). Accession details Presented by Dr. Willis in several instalments, 1994-2013. Additional material sent by Dr Willis: 8/1/2009: WIL/A6/8 5/1/2010: WIL/F/CA6/16; WIL/F/CA9/10, WIL/H/EN/7 2011: WIL/G/CL1/19; WIL/G/MA5/26-31;WIL/G/SE/15-27; WIL/G/WI1/3- 13; WIL/G/NA/1-2; WIL/G/SP2/1-2; WIL/G/MA6/1-5; WIL/G/CO2/55-96. 2103: WIL/G/NA; WIL/G/SE15-27 Biographical note Peter Willis was born in Yorkshire in 1933 and educated at the University of Durham (BArch 1956, MA 1995, PhD 2009) and at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where his thesis on “Charles Bridgeman: Royal Gardener” (PhD 1962) was supervised by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner. He spent a year at the University of Edinburgh, and then a year in California on a Fulbright Scholarship teaching in the Department of Art at UCLA and studying the Stowe Papers at the Huntington Library. From 1961-64 he practised as an architect in the Edinburgh office of Sir Robert Matthew, working on the development plan for Queen’s College, Dundee, the competition for St Paul’s Choir School in London, and other projects. In 1964-65 he held a Junior Fellowship in Landscape Architecture from Harvard University at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, DC, returning to England to Newcastle University in 1965, where he was successively Lecturer in Architecture and Reader in the History of Architecture. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

Annual Review

Annual Review 2020 Cover page: Ali Shahrour (centre right), the LebRelief focal point, delivering a Protection and Security session at one of the Safe Healing and Learning Spaces in Tripoli. Welcome Image: Elias El Beam, IRC We also welcomed a new cohort of bright students to the UK in 2020. Our scholars have shown resilience and are on track to successfully complete their postgraduate studies. These brilliant individuals join hundreds of our alumni who are making a Left: Wafic Saïd, Chairman of Saïd positive change in the Middle East through the knowledge Foundation. and skills they acquire at world-class universities in the UK. In this year’s report, you will find case studies of some of our Image: Greg Smolonski, Photovibe alumni who work in the healthcare sector, either providing essential healthcare services in their countries or contributing to groundbreaking medical research globally. The year 2020 was a challenging year which left a profound impact on people’s lives all around the world. Although it has In 2020, we celebrated the historic partnership between the been a year of grief and hardship, we have seen a renewed hope Saïd Foundation and the Rhodes Trust at the University of in the stories of people we work with every day. Oxford and held the inaugural Saïd Rhodes Forum which brought together some of the most respected voices and The Saïd Business School succeeded in ensuring the experts to discuss the current realities of the Middle East and teaching and research remained of excellent quality and to propose solutions to some of the most pressing issues facing above all, protected the safety of students and staff. -

The Political Economy of IMF Surveillance

The Centre for International Governance Innovation WORKING PAPER Global Institutional Reform The Political Economy of IMF Surveillance DOMENICO LOMBARDI NGAIRE WOODS Working Paper No. 17 February 2007 An electronic version of this paper is available for download at: www.cigionline.org Building Ideas for Global ChangeTM TO SEND COMMENTS TO THE AUTHOR PLEASE CONTACT: Domenico Lombardi Nuffield College, Oxford [email protected] Ngaire Woods University College, Oxford [email protected] THIS PAPER IS RELEASED IN CONJUNCTION WITH: The Global Economic Governance Programme University College High Street Oxford, OX1 4BH United Kingdom Global Economic http://www.globaleconomicgovernance.org Governance Programme If you would like to be added to our mailing list or have questions about our Working Paper Series please contact [email protected] The CIGI Working Paper series publications are available for download on our website at: www.cigionline.org The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Centre for International Governance Innovation or its Board of Directors and /or Board of Governors. Copyright © 2007 Domenico Lombardi and Ngaire Woods. This work was carried out with the support of The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Waterloo, Ontario, Canada (www.cigi online.org). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non-commercial - No Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecom mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice. CIGI WORKING PAPER Global Institutional Reform The Political Economy of IMF Surveillance* Domenico Lombardi Ngaire Woods Working Paper No.17 February 2007 * This project was started when Domenico Lombardi was at the IMF - the opinions expressed in this study are of the authors alone and do not involve the IMF, the World Bank, or any of their member countries. -

Bibliographical Essay

Bibliographical essay The following bibliographical essay is a far more comprehensive listing of scholarship on early modern violence than was possible in the print version of Violence in Early Modern Europe. Space constraints confined the published bibliography to a limited number of works, almost all of them in English. This listing presents scholarship – in English and a number of other European languages – that is pertinent to the historical study of vio- lence. Introduction As we saw in the text of this chapter, historians and sociologists have long sought the causes of behavioral changes among early modern Europeans. Max Weber was a pioneer in this search, as he was in so much else in modern social thought. He warned of the disciplining process imposed on individuals by the growing power of the modern state as well as by the power of other institutions such as the army and by growing modern industries. The result, he alleged, would be an “iron cage” for the individ- ual, a phrase he used in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. by Talcott Parsons (London: Allen and Unwin, 1948). Scholars who followed in Weber’s footsteps concurred with his asser- tion that a process of social discipline resulted from new power dynamics emerging in the early modern period. This was certainly the message of the philosopher Michel Foucault in his works Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, trans. by Richard Howard (New York: Pantheon Books, 1965); The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception, trans.